- ABOUT

- CONTESTS

-

AZURE: A Journal of Literary Thought

- AZURE Volume 7, Issue 3 >

- AZURE Volume 7, Issue 2 >

- AZURE Volume 7, Issue 1 >

- AZURE Volume 6, Issue 4 >

- AZURE Volume 6, Issue 3 >

- AZURE Volume 6, Issue 2 >

- AZURE Volume 6, Issue 1 >

- AZURE Volume 5, Issue 4 >

- AZURE Volume 5, Issue 3 >

- AZURE Volume 5, Issue 2 >

- AZURE Volume 5, Issue 1 >

- AZURE Volume 4, Issue 4 >

- AZURE Volume 4, Issue 3 >

- AZURE Volume 4, Issue 2 >

- AZURE Volume 4, Issue 1 >

-

ARCHIVES: VOLUME 3

>

-

ARCHIVES: VOLUME 2

>

-

Archives: Volume 1

>

- Literature Courses

- SUBMISSIONS

- BLOG

- Lazuli Reading Series

- Literary Links

|

There is beauty in this book, and there is genius; there is ink and fiber and a crinkling of pages, and yet it lives in my hands like a beating heart. This book has been important to me for several reasons, one of which is that it is the one of the extraordinarily few I have read that was written by a living author. I do not know how to speak of the poetry in this book because I can barely dare to touch it—but let me make no mistake by beginning with this statement: it is there, everywhere. Popova refers to a deeper culture than the popular (the real, perhaps? the universal? the delicately human?), and we hardly notice (for hundreds of pages, as she gently skittles through the lees) that we have not breathed the harsh artificiality of banality, posturing, tired phrases that form so painfully the deadening mist of our world. It felt delightful to relax; to unclench the fist of the mind; to feel secure that the next turn of phrase would be intelligent—would corporealize original thought and exude a flavor of empathy. To stop judging or wondering if it will be meet to turn the page—for it shall be. I experienced the strange sensation of forcing myself to read a book without a pen in my hand. Every conscious underline inevitably makes an unwitting statement about every non-underline, provoking a whole host of annotation anxieties; I decided to forgo my pen and take my leave of the whole vicious quagmire entirely. And indeed, unmoored to this implement that usually gives me the (erroneous) security that a beautiful sentence has not slipped through my hands unheeded and unremembered, I realized I was right to have foreseen this linguistic glutting, this constant shimmer. I felt lonely, at first (would anyone ever understand the genius and eloquence I have here encountered?); I then felt satisfied (they may not, but Maria Popova wrote it—that’s one person who has swum in this book with me—and several geniuses are here written about—perhaps their ghosts would consent to linger in my midst?); I finally, for better or worse, felt compelled to write this review. What is beautiful about Popova’s writing is what seems beautiful in her person—that she is so unabashedly in love with imagination, knowledge, thought, and the illuminance; she does not reach above the surface of the intensity to catch her breath in mediocrity, does not offer in her book the moments of levity that allow for the release of the sort of nervous laughter so characteristic of avoidance that percolates in crowds who have been confronted with something all too serious, something too vulnerable to own in a group. Popova plants herself in the center of the emotion—a position which is in academia seen so often as frivolous, an unnecessary caveat, an unwelcome but tolerated interloper upon the “serious stuff” of the intellect—and it is from emotion that her tale of historical wisdom begins. “Figuring” approaches the lives of people who, though immersed in the fields in which I consider myself obsessed (quantum physics, poetry, astronomy, and literature), I had very little detailed knowledge of. Popova approaches these figures first as people to be identified with, and only then as visionaries to be awed by (and awed, indeed, we are). I have always wished that non-fiction could contain this element considered so salient and so necessary in the judgment of “good” fiction; that which moves the heart, in that it considers the heart. And it is this thematic, emotional structure by which the book is so carefully ordered—not by character, not by chronology, but by the vicissitudes of hope and despair, struggle and transcendence, repeated generation after generation in much the same way. This design encompasses these (mostly) women’s atoms in an ever moving tide that composes a symphony with them, their contemporaries, Maria Popova—their steward into this century—and, finally, the reader. The pain and the heartbreak in this book is almost untenable; it rends the soul. And it is not mitigated by unprecedented successes that are ultimately offered to these women in their lifetimes—and yet, the experience of reading their pain is more sweet than it is bitter, for they are so deeply in love mostly with beauty, mostly with goodness, that it fills something in them that compels them against their flagging joy and illuminates a twinkle in their melancholy. That even in their heartbreak, they are a part—perhaps that in this, they are MOST a part. And a part of what? There is a thing that is to be held, made precious, relinquished; a nobility of intellect that is an honor to encounter—to notice suddenly, surreptitiously, in one’s own hands. I have to believe (without presumption) that there is something of this that animates Maria Popova, a poet and a scientist and a humanist in her own right, in “Figuring”. She has created a history for women whom history had contentedly forgotten. She dug personally, with her hands and fingers, and breathed upon the pages and letters that were privately exchanged, written in the most intimate moments, between these women and their loved ones; what is it to receive a letter? And who was it written for? If we felt from it, was it then for us? I believe so. And in making it so, Popova has done such a meaningful service. For me, this book offers (paper and ink that it may be) an infrastructure to frame my actual, physical life decisions according to measures not to be found in the world of something so mere as one’s dimensional time; to be able to put the darkness in a place and to appreciate the beauty and to create a beauty without having solved the melancholy to which it might forever be associated; and for this to be enough for a lived human life. The acceptance may never come, or the relief in a struggle; the alienation may be persistent and the resistance, at times, intolerable. But eventually--even if years after their deaths—the things these women spent their time on mattered. There is a technical resplendence to the style of this book; “Fragmentary” may be bandied about, I know, as a failure of cohesion. To me, Popova has fragmented disciplines, times, hearts, and achievements, and welded them into a new (“creative” in the pure sense of the word) coherence, designed to illuminate ragged edges once thought smooth, surprising similarities one thought jagged (if the cover is any indication, this seems entirely intentional, no less than overt!). The constant references to time, to numbers, to counter-simultaneity, to relationships between figures apart in one dimension and yet so narratively, so empathically, so missionally connected. It is not several biographies concatenated (although it is that, I suppose, but so very reductively); it is ONE biography of a particular strain of the human race and its place within a universality. For is that not Popova’s point, after all? Stardust! It did not matter that these people were dead or that I would never meet them; it does not matter that Maria Popova is alive and I have had the privilege of hearing her speak but may never have the chance to speak to her. Thank you, Maria, for doing the years of painstaking research and crafting every sentence to its lyrical pinnacle, when you must have known—like Fuller, like Carson, like Dickinson—that you have the sort of fame that had you written something you had polished off in six months it would still have betokened a residue of your genius, would still have been commendable, would still have instantly sold millions. I suspect that, even knowing so, you could not—like Carson, like Dickinson--bear to cover a canvas with less than the entirety of the beauty you envisioned. So thank you for taking the incorporeal thoughts borne of the sizzling of atoms and arranging them in this particular way, and committing them to ink, to fibers; it has been so special to me.

0 Comments

In this episode of the Lit Mag Love Podcast, host Rachel Thompson talks with Sakina Fakhri and Diana McClure, founders of Azure Journal. They talk about the connection of interiority to empathy—how writers give readers that inner experience of something they don’t understand. "It's important to maintain that rawness in the writing. It's pretty clear that this is an avante garde publishing experience and for writers who can craft sentences that don't make readers want to skim to the end, because we have no idea where it will go. So they're looking for a lot of innovation and most of the work that they publish taps into some philosophical element. They publish unique, cerebral empathetic work. They are looking for submissions of things they have not imagined before. They are looking for finished work." - Rachel Thompson

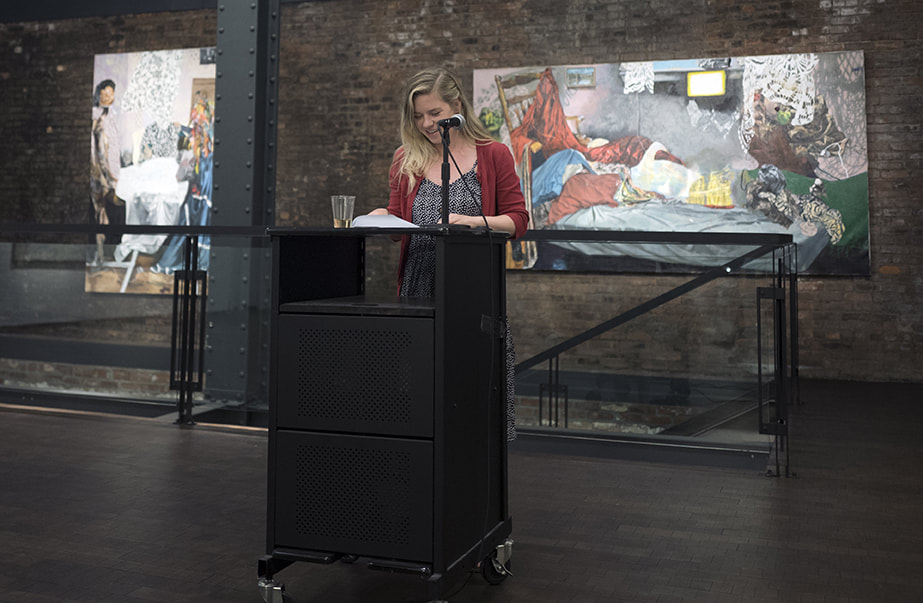

Let us put aside, for a moment, memories of the great writer's masterpieces such as If on a winter's night a traveler, Invisible Cities, and Cosmicomics; let us look at The Baron in the Trees as a creature basking in its own form. It contains, undoubtedly, the evidence of an idiosyncratic intelligence and sardonic playfulness that pervades nearly every sentence that Calvino commits to paper--an atmosphere of inveterate seriousness tempered by the humorous pigment that has, as its face, a frank sincerity. That is, the absurd is presented as the innocent. The Baron in the Trees is told from the eyes of just such a narrator: A younger brother, with an undertone of even-keeled awe, tells the story of his older brother Cosimo who--following a casual disagreement at the dinner table--takes to the trees, never to set foot upon the earth's soil again. The tale is told quietly and humbly; the absurdity is acknowledged (for it is no dystopia nor utopia) but does not send up its flares--that is, the absurdity itself is not the source of the humor. The humor is in the smaller things. And some logistical pyrotechnics are successfully employed in transferring to a secondary character (the brother/narrator) enough information to tell a story about a protagonist who is, in some essence, isolated; if not for this device--if not the necessity for a second person to know the story--one wonders if Cosimo's life might have played out differently. Calvino's set-up feels immaculate, entirely (for we cannot, despite ourselves, completely block out memories of the great writer's masterpieces) Calvinian in its edifice of quirks. Somewhere beyond the first two-thirds of the book, however, the humble tone disappoints; the playfulness of describing a life in the trees is replaced by a hinting undertone of drudgery on the part of the author and a concomitant languor on the part of the reader; the younger-brother narrator, meanwhile, hangs in the balance and continues a tale which it seems the writer is loath to tell and the listener is weary of hearing. Still, the experiment embarked upon here is admirable--we must give Calvino his due. Narrating a life lived entirely in the trees presents, one presumes, some of the same creative challenges as living a life among the trees. Alongside his contemplation of the obvious philosophical and allegorical components, Calvino must figure out how to provide for all of the very human needs that Cosimo requires (bathrooms, clothing, food, companionship). To Calvino is attributed the creativity; to his fictional Cosimo the execution. For the fascinating insights contained therein, I entreat you to venture into The Baron in the Trees. Here, however, I would like to delve into an exploration of the potential reasons behind remarkable and sudden change in tone of this creative, would-be vibrant tale throughout. I do this not to malign Calvino--for he has more than proven himself--but to learn something about the narrative art and about what delights in the style that is distinctly Calvinerious by learning how it doesn't fit precisely into the corner he has wandered into with the second half of this book. The devolution begins far before this point, but becomes apparent when Cosimo introduces his desire and embarks on the pursuit of his love interest. One wonders if it is the precise point at which the tenor of the story could not be upheld further? That perhaps a deeply emotional story with a rather generic counterpart on earth undercut the novelty of a life in the trees that brought such vigor to the first half? Or, alternately, is it that Cosimo is interesting as long as he is peerless--that the introduction of a paramour was too close to a reduction of his uniqueness? Or maybe it is that Calvino, a writer of concatenated tales that tend to leave off pivotally with the reader's mouth agape, was not a man meant for the conventional denouement? In any case, the storyline meant potentially to "humanize" and "normalize" Cosimo is, in fact, the literary death of his spark of life. The trajectory of Cosimo's evolving life in the trees is as pleasantly gnarled (please excuse the pun) as its setting. Until this evolution reaches its plateau in the love story, the progression is fascinating--at every challenge (though we know he will stay in the tree), one expects that Cosimo will depart from what might be considered the ideals of human life upon the earth and that he will have to become animalistic (for it is they who are thought to be built to among the trees), a transformation which would be interesting enough in its own right; instead, however, each challenge refines Cosimo and exalts his lofty (again, if I may be forgiven for the pun) station. What Cosimo lacks throughout, and very conspicuously so, is fear. Whereas Cosimo's father lives in constant terror of the tenuous nature of his own noble title, Cosimo braves human, animal, and climatic adversaries with little attention to the consequences of a potential failure. And, thereby, he acts the part of a true man of status, a "baron" in his own right, in that it is impossible for any person to achieve a station from which to threaten his self-appointed authority. And perhaps, at last, *this* is why the story of his desperate love is so disappointing--because it is the diminishing of an evolution that has been so fascinating to watch, and because the fearless Cosimo becomes at last identifiable and mundane. Furthermore, there is no buttressing, no substance created in the first half of the book, to support a robust love story; there is only a resistance to believe that Cosimo is anything but the delicately awe-inspiring figure drawn by his little brother. By Sakina B. Fakhri "...a howl of such outrage as to stitch a caesura in the pulsebeat of the world." Blood Meridian is a gentle, rhythmic scraping of the inner maw of a universal wisdom. This wisdom (personified most literally in the dark character of the "judge" but present as an undercurrent mist everywhere else) girds the prose - which is delicate and waltzing - and renders profound the violence and the depravity, the human wickedness and the horror that, without McCarthy's thoughtful hand, might have left us merely a residue of the nightmares of the American West of 1848, a story of "itinerant degenerates bleeding westward like some heliotropic plague". "I ain't heard no voice, he said. It is precisely the nightmarish, colorful quality of the gore contained herein that had me resist the reading of this book that sat on my shelf for over two years; a book whose spine I awoke to every morning amidst the blur of Dickens and Woolf, who might never have guessed that their particular worlds of struggling Victorianism might be slotted unceremoniously alongside this roiling, described "neo-Biblical" tale of a scalping, excrementary world. And yet... the beauty contained in this book rivals the beauty contained anywhere. Take this fanciful description of a massacre of mules: "... the animals dropping silently as martyrs, turning sedately in the empty air and exploding on the rocks below in startling bursts of blood and silver as the flasks broke open and the mercury loomed wobbling in the air in great sheets and lobes and small trembling satellites and all its forms grouping below and racing in the stone arroyos like the imbreachment of some ultimate alchemic work decocted from out the secret dark of the earth's heart, the fleeing stag of the ancients fugitive on the mountainside and bright and quick in the dry path of the storm channels and shaping out the sockets in the rock and hurrying from ledge to ledge down the slope shimmering and deft as eels." There is the cradling of puppies - one in each hand - drowned in a river and shot by pistols for the mere sport of a deadened spirit; but then there is the gentle sniffing of horses through the precisely described foliage of the mountain terrain. Each is described in gentle, rolling prose, without crescendo and without warning; at times, without punctuation. An extreme quietness overtakes the tale throughout, the ravages of battles equal to the spindrifts of the breathtaking desert landscapes, of silent lightning that "rigged a broken lyre upon the world's dark rim" and of "secular aloes blooming like phantasmagoria in a fever land". Even in the harshness of the landscape, the enemy of man, there is awe in McCarthy's pen: "the cannonballs were solid copper and came loping through the grass like runaway suns"; "the hail leaped in the sand like small lucent eggs concocted alchemically out of the desert darkness." If words are colors, then McCarthy excavates a palette with a wider range of pigments than can be counted in the gossamerity of a fly's wings. One feels the confidence in the descriptions that McCarthy's desire does not exceed his grasp, for he has available to him such a storehouse of vocabulary that one must assume that he has described every iota of every landscape exactly as he must have intended. "They moved like migrants under a drifting star and their track across the land reflected in its faint arcature the movements of the earth itself. To the west the cloudbanks stood above the mountains like the dark warp of the very firmament and the starsprent reaches of the galaxies hung in a vast aure above the riders' heads." I had nearly quit the book early, fearing that the beauty of the prose would lull me into a state of complacency with the violence - I found untenable the thought of being made to *enjoy* these trenchantly described horrors. I feared that no character, though each suffers, would draw my sympathy and therefore I would read the novel without heart; for each character in Blood Meridian suffers, but each in turn causes unabashed suffering. But somehow, evident even a few pages in, there is a softness and a generosity in the treatment of these souls that manages to equalize the humanity of both sufferer and suffered: "... they listened to their breathing in the dark and the cold and they listened to the systole of the rubymeated hearts that hung within them." What furnishes the gravitas of the book throughout is McCarthy's resistance to ending a sentence, to beginning with the physical and ending with the mystical. He stitches pathways between worlds where our minds tend to roam only in one or the other: from "turds of goats" to "shapes capable of violating their covenant with the flesh that authored them": "In the days to come they would ride up through a country where the rocks would cook the flesh from your hand and where other than rock nothing was. They rode in a narrow enfilade along a trail strewn with the dry round turds of goats and they rode with their faces averted from the rock wall and the bakeover air which it rebated, the slant black shapes of the mounted men stenciled across the stone with a definition austere and implacable like shapes capable of violating their covenant with the flesh that authored them and continuing autonomous across the naked rock without reference to sun or man or god." Or the opposite - the corporealizing in an instantly recognizable image a pattern of human relations as old as a son and his deceased father. "He will not see him struggling in follies of his own devising... He is broken before a frozen god and he will never find his way." What becomes patently clear is the humanity that is thrust under the fabric of the characters and their actions; a humanity that breathes in and out slowly throughout the course of a book, and you realize that the thing upon which you repose is grander than you thought, and your vision smaller - what you sit upon is a warm, heaving chest and it has been breathing under you always, and you carried along with it with your comrades, every one of you a piece of the general fabric among which humanity is disseminated. "Everbody don't have a reason to be someplace. The deeper into the (often very literal) darkness that McCarthy leads you, you expect to suffocate. But suffocate you do not! Because you feel not that you have been taken out of the world - not that you have been denied - but that you have been taken into it and a certain thing that is not amorphous but is hard has been revealed to you. "About the fire were men whose eyes gave back the light like coals socketed hot in their skulls and men whose eyes did not, nbut the black man's eyes stood as corridors for the ferrying through of naked and unrectified night from what of it lay behind to what was yet to come." "...drove forth the last fragile race of sparks fugitive as flintstrikings int he unanimous dark of the world." "If much in the world were mystery the limits of that world were not, for it was without measure or bound and there were contained within it creatures more horrible yet and men of other colors and beings which no man has looked upon and yet not alien none of it more than were their own hearts alien in them, whatever wilderness contained there and whatever beasts." There is revealed, in effect, *more* in which to breathe, and more sympathy and beauty and despair to be found than could have been thought possible. "Sparse on the mesa the dry weeds lashed in the wind like the earth's long echo of lance and spear in old encounters forever unrecorded." By Sakina B. Fakhri M.K. Rainey - published in AZURE Vol. 2, Issue 2 (short fiction) and AZURE Vol. 2, Issue 3 (contest winner) - read from her experimental short story "Crosshatching" at April's "Pen and Brush Presents," a reading series founded by Kate Angus and hosted by Pen and Brush.

The series supports the work small press editors do in identifying excellent writing (as well as supporting the writing itself) by featuring exciting new work by established and emerging authors. For over 120 years, Pen + Brush has been dedicated to promoting the work of women in both the literary and visual arts. Pen and Brush provides a platform to showcase the work of emerging and mid-career female artists and writers to a broader audience with the ultimate goal of effecting real change within the marketplace. AZURE: A Journal of Literary Thought, Volume One is now available in print at McNally Jackson Books in Manhattan and Williamsburg, Berl's Brooklyn Poetry Shop, and Bookculture (112th St, Manhattan)! Support your local bookstore by ordering a copy with ISBN # 978-0-99-942430-8.

We are pleased to announce that AZURE: A Journal of Literary Thought is now a Sponsored Artist Project of New York Foundation for the Arts! If you are enjoying yourself on this website, please feel free to make a donation!

We have a lot of fun supporting unique literary perspectives and genre manipulations that arise from eclectic intersections of an avant-garde ethos, experimental writing, culturally rich plot lines , and a touch of dark humor. Your support as writers, readers, and financial stakeholders will help make AZURE: A Journal of Literary Thought a sustainable production for years to come. Thank you! |

AuthorThe Lazuli Editors, heightening the perception of the magical. Archives

March 2019

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed