What had he done?

He didn’t have a mind to answer with. His mouth too destroyed to hold language.

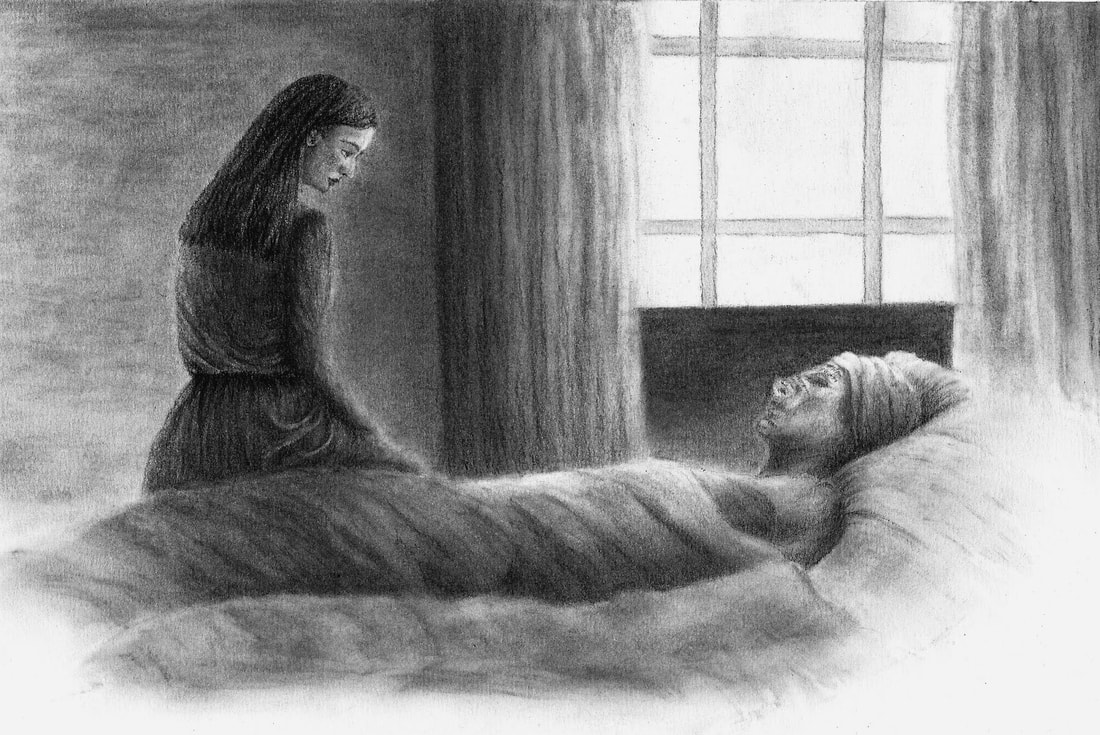

He lay on their bed, face split to the pink flesh. A soft, tender-swollen from forehead to chin, grazing the left eye, turning the whites. She had to look at him, smelling that smell that belonged to the unseen, the inside, because he refused to go to the hospital. He writhed, screamed with his too wide mouth, then fainted. She thanked God their son wasn’t home. She sewed him shut with a needle she used to mend denim, swallowing bile as she punctured inflamed skin. She watched his unflinching sleep between dabs of rubbing alcohol. When he came to, he moaned through the pull of the thread. She wanted to soothe him, but pain like that don’t want company.

0

For weeks, Ishmael lay on his back, staring down at his feet because he couldn’t look anywhere else—crying. The salt from his tears reminded him he was alive; his sobs rattled in his chest like triumphant laughter. Delirious from self-pity. Or fear. He’d seen it again. No, but he couldn’t have. There was nothing to see.

1

Menelik had nightmares about a man sitting in black, surrounded by black, cackling until tears welled in his six jaundiced eyes. He woke in terror, ears faintly ringing. He missed his daddy. In spite of what his daddy had done. No doubt that cryinglaughing man had something to do with him being gone. What else could be so funny? The secret he kept tickled him pink.

“Mama,” Menelik came running into the living room late at night, already bent on weeping. He shook her shoulders until she pulled him onto the couch. Draped her arm over his thrashing heart.

Weightless in sleep, Namibia told babyboy what nightmares are: longing churned into a spell, opening portals for fears to crawl out. You have to be brave. Can you? I shouldn’t ask you to. You shouldn't know a world to be brave for.

2

Namibia didn’t want Menelik, or anyone, to see Ish. Not until he had eyes and a mouth and a mind.

Ish would want it that way. She was sure of it.

But people started to ask where he was.

He can’t miss this much work, Namibia. He can’t. There’re people out here, young idle kids, waiting! for something to do. Now, I gave Ish a job, because I know his people. Been known his people. But at the end of the day, baby, I run a biznuss and his people is dead. He better be in tomorrow or that’s it, girl. That’s it.

When tomorrow came and Ish did not, she went to the store to plead with that greedy man. She stepped into his poorly lit mini-mart. Nobody ought to be scrambling to work in this shit hole.

Under the fluorescent lights, between the canned foods and the dry ones, she spoke softly to him. She knew she had pretty, convincing eyes. They were slits in her head, but when she fixed her pupil on another, that body was hers until she said all she had to say.

“What’s happened to him?”

“Well Mr. William—he’s ill.”

“Well I know dat much! When my wife got home, she said he was talkin to himself, told me there was blood, and that he’d thrown up too! We had to bring the cleaners in off schedule. Cost us a fuckin’ dime. That’ll have to come outta his next check but we can talk about that later. What I wanna know is: What kinda sickness make you act like that! Sheesh. He scared my wife. He been ill for three, fo’ weeks! What kinda sickness he got?”

He was concerned for himself. His safety. Any man that’s been sick for that long has got to have caught his death. Namibia kept talking, circumventing his questions with neutrality, uncertainty, hopefulness, and he kept listening, assuaged by the frail, crisp sound of her voice. But he had already made up his mind. He won’t fire the boy. No need to. He’d just wait for the news of his death to reach him in the coming days, then pick one of those curb-sitting men to mop for nothing. No reason to give Namibia more heartache than she could take anyhow.

“Ish.”

She appeared at his side, smiling a little. Something had gone right today. If—when Ish got better, he could pick up where he’d left off. To have his job back would be good. Plain good. Show him how normal things still were. How ready normal was to have him. She’d keep the news to herself. Tell him when it mattered.

Ish, who could now turn his head and speak when hydrated, looked at her. She loved him, in spite of what he had become.

His voice a broken stream of breath, he often spoke nonsense.

“Name.”

She didn’t like how his face looked. Two jigsaw pieces struggling to fit together. She fixated on the parts of Ish’s skin that remained the color of fresh things changing season to stave off the hot twisting and knotting in the back of her throat.

He used to be a handsome man.

“Name…I….saw.”

If she wanted to see that man again, she’d have to look at her son. She had already begun searching for him in the child’s face especially while he slept. He took her eyes but Ish’s complexion. Took his hair, but her hands. It became a game on nights when she couldn’t find the peace to sleep.

She stared at the space above Ish’s right eye.

“Yell….ow.”

She nodded and shook two pills out of the bottle. Amoxicillin. Originally for a urinary tract infection that had healed on its own. She’d figured they could help him. This was the reason she’d come into his room: to give him her antibiotics. Otherwise, she occupied the living room, where she slept to avoid the sound of suffering, where she sat for what felt like hours glaring at her reflection stretched across the blank television screen. In the silence, she starved her desire for answers.

(What did her son think of her? When had Ishmael lost himself? Who had taken half his face? Would they come for his family too? Was this their end? Was it best to just—go? You can’t leave a sick man.)

“…saw.”

She sat on the edge of the mattress now. She picked up the lukewarm water on the bedside table and angled the straw toward his twitching mouth.

“Yellow.” Ish lifted a finger. Pointing.

“That’s enough.” She pinched a pill. “Rest now.”

3

Was he in pieces? The animal Ishmael tried not to look at told him that he was. And apologized for it.

He didn’t want to admit that he believed what the animal had to say. He didn’t want to feel the urge to respond to an apology that should not exist.

He was like this because of something he’d done. He must have fallen. Hit his head. Nothing makebelieve had done this to him.

Ishmael needed to see himself. He wanted to see himself to disprove the animal and stop the horrific visions of raw dismemberment. He knew he was healing, because he could drink from a straw. There was the stab of his jaw, throat, and lips as they flexed and pushed to gain control of liquid and sometimes solids, but behind this sensation was the pulse of regeneration. It swallowed him. A heartbeat trapped in his head, bleeding into his sense of self. When left to that throbbing, he’d start to think about what it meant.

Name had refused his request for a mirror, though. She clearly didn’t understand the need to see oneself whole. He needed his son to bring it.

The emotions he felt at the sight of Menelik were too intense for regular visiting. The first few times, he’d bled and sobbed into the stitches that Name so meticulously refreshed with aloe. After a while, she only let babyboy into the bedroom once a week; early in the morning when the cool air and immobility kneaded the swelling down to lumpy blemishes he could see over. Usually, around that time, Namibia showered and dressed for work. He’d have to talk to Menelik then. He’d have to tell him to bring something. A mirror, a spoon, a laptop screen. It didn’t matter. Just bring it.

4

Cause Ish won’t dyin’ soon enough, the greedy man fired him. He called Namibia at seven-thirty in the morning and said, when the boy gets well, he don’t need to worry bout comin’ in here. She sighed into the receiver, Fuck you.

She listened to his insults while undoing her satin headscarf and stepping out of her house dress. As if she’d never been called a blackbitch befo’.

5

Before William called to break their family into smaller pieces, Menelik shuffled into the room with his eyes on the carpet. He made it to his father’s side like that. Head down, eyes tracking the lint in the carpet fibers. He saw an ant. Small and black traveling across mounds of mute, beige landscape.

Where was it going? Where had it come from? How far was its home? There was no home here.

His mother had cut his hair the night before. The skin behind his ears burned. He used his thumb to press on where it hurt the most. The pressure somehow relieved the pain.

He wanted to have long hair like the girls in his class who took combs out at lunch and let the teeth glide through. The sun seemed to shine on those girls.

He didn’t have nightmares anymore, but his mother’s empty eyes, his daddy’s closed ones, they chilled him to the bone. And it seemed that all the rooms in their apartment never turned bright anymore, even with the lights on. Made him wonder where brightness truly came from.

Either way, Menelik wished for a little more sun to fall on him.

In his hand, he held a pocket mirror that he’d taken from his mama’s purse. It was gold with a sticker on the back: Balmain. He called it Ball Man. He’d taken it for himself a while ago. He liked that it looked like the sun. His mama once asked him if he’d seen it and he said, No, never. At the playground, while his classmates hollered on the jungle gym and leaped off of swings mid-sky, he stared into his own eyes. Would he turn mean like his daddy one day? Was meanness something you could find or see before it came and claimed you?

6

Ishmael stared at Menelik’s oiled scalp. He wanted to put his nose against it. Let the tea tree oil burn the inside of his nostrils, get into his wounds and burn them too.

Before Ishmael became what he was now, Menelik would stare into his father’s eyes with such intent it made him question the purpose of sight. He’d stare into his father’s eyes as if he needed to find something truer hidden behind that unconvincing sheen of knowing. He stared at Ishmael looking for what his father wouldn’t say, couldn’t say, didn’t know should be said about being his son, the son of a son. Waiting for him to admit to his own ignorance, perhaps. For him to confess his failure to do anything more than mimic the bonds that replayed before him as a child. He was not a creator, after all. A pattern following a pattern at best.

Now, Menelik seemed more fascinated by the rug than by his own daddy, his own incredulous fate. Ishmael was seeing scalp. This was his mirror.

The animal stepped forward.

Ishmael flinched.

Its shadow stretched through the boy’s body.

“I am so sorry.”

7

Namibia stood in the hallway in a shower cap with a towel wrapped around her damp skin, trying to remember what she needed to do next. William’s call had thrown her more than she was willing to admit.

Menelik came out of his father’s room with dry eyes. He walked past her with something shiny glinting in his palm. Was that her damn—?

“Daddy is crying.”

She watched him disappear into his bedroom. His impassivity a concealed dagger held down by his side. She bit the inside of her cheek, missing his bad dreams, times when his fear reminded her of innocence, of fresh malleable life. She should have never told him about bravery. She should have let him cry into her arms for as long as he needed.

8

Menelik had a bunk bed even though he was an only child. He used the top bunk to hide his thoughts. His journal was tucked beneath the second mattress with his pen. He climbed up the ladder, pulled out his journal, and swung his legs off the side of the bed. Yesterday he didn’t have much to say. He described an incident in class when he’d yelled at Brendan for calling somebody’s mama a hoe who licked clits for two pennies. For some reason, it felt like Brendan had really been talking to him. He put his pencil on the paper, but the words wouldn’t come. He needed them to. He waited. He flipped through his journal, kicking his legs faster and faster.

Months ago, on his eighth birthday, his daddy broke his wrist. The pain was unlike anything he’d experienced. It reminded him of nothing and birthed a solitude that lived at the base of his neck.

Daddy had never done anything like that before. Never say never, Mrs. Pedington says. I’ll never like the color blue. Never say never. I’ll never play with you. Never say never. I’ll never hurt you again. It was an accident. Something to do with him playing with his toys in the living room and not cleaning them up. Something to do with him not listening. Daddy hugged him in the hospital when Mama told the doctor that he’d fallen off his bike. They must have looked like a family.

“Promise me you’ll be careful next time,” the doctor held out a red lollipop, like he was some kind of baby, “you’re a brave boy.”

“I’ll be careful,” Menelik said. “I won’t fall again.”

In the hospital parking lot, he dropped the candy behind a tire.

That day, he’d only written that his wrist was broken—he had a cast to draw pictures on now.

He flipped back to an empty page. He put his pencil on the page. He wrote the letter “I” then threw the journal across the room. It smacked against the wall. He liked the sound. He threw the pencil. It bounced back and landed mutedly on the carpet. He needed more. He held the pocket mirror in his hand. He grimaced at his wavy reflection in the gold. He felt something in his stomach drop as if he were in a car going too fast over and down hills. So fast the trees outside the windows blurred. The mirror popped and shattered. He hadn’t even felt himself throw it.

9

Ishmael was the kind of man that understood beauty, and so loved to see it. When he was a child, he saw it without looking for it and knew what to call it. God. The soft, black shadow between teeth that could only be seen when Mama’s joy overshadowed the weight of a man’s absence. The dust dance does when the sun shines through dirty kitchen windows and bedroom curtains sullied by absentmindedness. A Black girl’s brown eyes when she looked at her own figure.

He remembered when he first saw it in himself. It wasn’t like Always. His eyes never rested upon himself like it rested upon the world around him. It wasn’t like it was always there. He had to look for it. Especially after his mama was finished with him.

First it was his hands. He’d stare at them against the textures of the universe, intrigued, thrilled by their softness. Then his teeth. White, straight. He didn’t need braces like some kids. His eyes. They weren’t hazel like Jamal’s, but they had their own light. Not simply a light’s reflection. No, it didn’t mimic. The light was inside, behind. A girl he once knew called it a twinkle. He gotsuh twinkle in his eye. Name, when she saw it, called it hers. She was fourteen, looking into his face like he looked into things he cared to know, and said softly after a brief, playful hum: that’s mines.

Not like this happened all at once. Not like he loved himself all at once. Saw that beauty some loved him for by the day’s end. No. It took years. Even years after Name’s hum. But once he had it, he’d curled his fingers around its neck, so tight. So tight. Nearly cutting its breath so that it lay still in his heart and his mind, unchallenged because it was so harmless. And now his son couldn’t look at him.

And now, he was left alone with it. His broken mouth quivered.

“What are you? What have you done?”

The animal showed its teeth as if to say this is what I am, this is what I do.

“You should not have to ask. I belong to you.” It did not smile yet its growl rolled like pleasure. “You summoned me with a broken wrist. Here, look.”

Its many silken limbs melded into one small child’s: a little brown arm with a lump where there shouldn’t be.

Ishmael averted his eyes, sucked in a panicked breath.

The animal snickered. “Why won’t you look? Aren’t you proud of me?”

“Please don’t hurt me anymore. Don’t ruin me.”

“I am sorry,” it whined. “I must show. You must look. I only want to help.”

Ishmael began to cry. “Leave.”

It stretched long and thin and jagged, released a tremorous hiss.

“So soon?”

“Yes. Please. Please.”

“I told you how!” Wet, dark eyes swam in the sea of its body, all relentlessly staring. “You try to forget me and now you don’t know the way out! Remember me, Ishmael. All of me, Ishmael. It will be painful,” its teeth shone crescent moons, “you’ll find what you’re looking for.”

10

The day Menelik had his cast removed, the heat peaked and lit sparks in people’s subconscious minds. Ishmael was at work, unblemished and whole, feeling the full spectrum of his personality. He was gorgeous. He was not. He was confident. He was not. He was hard-working. He was not. He was charming. He was not. He was floating and yet ever present. These sort of fits only happened when he smoked too much. And although he had tried to control himself that morning, the thought of spending eight hours in William’s shop made him incredibly sad. So sad that Namibia had even noticed a certain intensity in his morning routine. The way he brushed his teeth so loudly she wondered if his gums were bleeding a little.

He wanted to call Namibia. They weren’t as good as they used to be, since the accident with Menelik’s wrist, but her voice would still ground him. And a part of her would be happy to hear from him. He was sure of it.

He reached into his pocket and felt for his cell phone. It wasn’t there. He searched in his backpack. It wasn’t there. Alarmed, but not desiring the anxiety of being alarmed, he sat back down and decided it was not meant to be. He was not supposed to call Name. But he thought of her perky, earth-toned breasts like young yams and rested into the image. Lost in a dream sequence of brown bodies in motion, he had not noticed the fog on the acrylic divider. “You miss me?” Suddenly his insides spun and heaved; vomit singed his tongue. His eyes couldn’t grasp the world he belonged to. Because if so then what was that? What was that? that that that what was—he collapsed onto the concrete floor.

11

From where she stood in the hallway, Namibia heard what could have been the drone of prayer. (Her father kneeling with his ninety-ninth reverence pinched between knuckle and breath.) She moved toward their bedroom door. She pressed her ear against the wood—daddy? She clutched her towel to her body. From inside:

“Noooooo I don’t want to remember you. There has to be another way.”

“I don’t want to remember you.”

“I don’t want to remember you.”

Who was Ish talking to? Who was he talking about?

She gripped the door handle. Left her hand there until the metal warmed.

12

At eight years old, Ishmael stands on the potty training toilet that nobody uses anymore, except his big brother Jamal who, when he thinks no one is watching, places it beneath cabinets to reach snacks at night.

Up high, Ishmael notices the flushed skin on his neck. He touches the half moons on his throat. He can see blood pearling on his chin and forehead. He can see the color red blanketing the white in his left eye.

He never knew he could look like this.

Like nobody.

He leans forward over the sink, nose nearly touching the glass, and turns his face in the light. To see this new nobody better.

He thinks it's his own breath fogging the mirror.

Slender, yellow tendrils the length of his torso curl around his shoulder, graceful and firm.

“Did you make her hurt you? You should be kinder to your mother.”

13

Namibia found a bead of strength in her wrist. She pushed their bedroom door open. Her towel unraveled from around her, fell to her ankles.

Ishmael was on the floor, as if he’d attempted to crawl to the door and had failed.

Tangled in bedsheets, he beat his head with a fist, his face coming apart:

“I don’t want to remember you.”

“I don’t want to remember you.”

Breathless now. “I have to.”

He sobbed. “I have to.”

14

Before Lidia stopped by her husband’s store to help herself to a pack of cigarettes and an Arnold Palmer and found Ishmael in his own blood and vomit. Before Ishmael woke in his own blood and vomit. Before Ishmael had fallen, he’d seen an animal that was too frightening to call familiar. Its breath fogged the acrylic divider. Two perfect wet circles expanding, contracting, expanding. Rivulets of moisture pearled on the hard plastic barrier. In the finite space between exhales, black eyes gleamed like polished eight balls.

The divider between him and it melted, became fondant, hissing with unnatural heat as it collapsed onto the cash register. It pooled over the store’s back room keys, the Fireball and Smirnoff nips, the cellphone he couldn’t find, and singed his unbelieving hands. The moment he jerked away in shock, the animal reached forward, as if to keep him from falling backward, and swiped him across the face.

Ishmael trembled against the concrete.

He pressed his forehead to the floor. He held one hand to the hot-wet of his cheek while the other extended stiffly above and over, protecting and pleading.

“Now feels like a good time,” the animal made itself small. It stood in the fluids crowning Ishmael’s head. “You think all is well, it is not. You think you have been spared, you have not. You believe you deserve to play in a faultless mind, you do not. You are not a child any longer.”

15

Namibia backed into the hallway, closing the door to her husband. She stood naked against the wall, breathing, nostrils flaring, eyes unseeing. She could still hear him on the other side. She ran into the living room and searched her purse. She found her cellphone. She pressed 9-1-1. She couldn’t handle this. Not anymore. The stitches yes, but—Her thumb hovered above the call button. What if they come and make it worse? What if they come and lock him up and never let him out? (Would that be so bad?)

What’s the right choice?

What’s the right choice?

What’s the right--

Menelik screamed. The sound pierced her chest. She dropped the phone, clamped a hand over her mouth.

Where was Ishmael?

Had he?

Could he?

Again?

16

Ishmael falls from the training toilet. Against the bathtub, he hides his eyes as if they were the source of his troubles, clutching them shut against the sound of things everywhere.

He shivers on the floor, muscles cramping as he pulls his body inward to stillness.

The warmth of his own urine, weighing him down at the hips, convinces him he’s safe.

He pushes himself from the porcelain and rests on the bathroom mat. There is only the steady drip of the bathtub faucet and Jamal, standing in the doorway, watching him. Their mother’s screams carry from the living room and Ishmael thinks they’re for him.

Automated clapping. The muffled voice of the television. No—she’s laughing.

“What happened?”

“I saw sumthin.”

“Damn.” Jamal turned nine last month. He is learning to watch people burn. “Whatever it was fucked you up.”

Reluctantly, Ishmael removes his pants and underwear—with the Power Rangers doing athletic jumps around his thighs—and Jamal stands there, smirking.

“Go away.”

Ishmael tells himself not to cry.

“Make me.” Jamal crosses his arms. “Lil boys that piss their pants don’t got no rights.”

Ishmael reaches for a towel and wraps it around his waist. He feels bold.

“How come you don’t get hurt?”

“I don’t know, man.” His brother shrugs.

“You’re lying! You’re a damn liar!”

Ishmael watches his brother squirm. The silence angers him. He jabs a finger.

“Mama don’t like me because I don’t look like you. I look like him.”

Jamal shrugs again. His words have abandoned him.

Ishmael steps into Jamal, shoves him. “You let her! Why you let her!”

Automated clapping. Screamlaughter.

Jamal opens his mouth, a sentence swims in the well of his throat. He snatches it quickly, before it can evade and drown: “What am I supposed to do, Ish?”

They stare at one another. Ishmael doesn’t know the answer. They are only kids and Mama is all they have.

Jamal hesitates, but eventually he allows himself to turn and leave.

Ishmael stands alone, then in the shadow of the animal, whose warm body at his back might be mistaken for a comfort. As its delicate limbs spiral around his chest, thread between his thighs, and twist around his neck, Ishmael hardens into an ancient and implacable rage.

17

Namibia pushed open her son’s door hard enough for it to swing and hit the wall. She didn’t know what she would do if she saw Ish.

She found only Menelik, seated on the top bunk, quiet now.

“Mama,” he said. He stepped down the ladder.

He started to hug her, but pulled back. He rubbed the wrist that clicked when he did things, his face streaked with salt.

She shook her head slowly and grabbed him by the shoulders. She brought him to her. She curled her body around his, willing her limbs into armor. She rocked. She rocked and moaned an almost lullaby. His body swayed and swayed. Her abdomen grew damp where his face and her navel met. She trapped a wail against the roof of her mouth. She had words that she could not speak.

Not yet.

She wasn’t sure when. When he was old enough to forgive. When he was old enough to know that she must ask for his forgiveness.

18

The store’s concrete floors shook and slanted as the animal neared. It touched the hand that Ishmael held against his torn face, stroking the curvature of his pleated skin. Ishmael whimpered, jerked away.

The animal brought its chewed mouth to Ishmael’s ear, the heat of its tongue inches from his skin: “You thought you could make a big happy! faaamily.”

Its voice whipped and crashed like roaring currents; He could not hear the boss’ wife enter.

He did not see the wife peer through the unscathed plastic divider, over the intact register, past the perfectly aligned alcohol nips. He did not see the cigarette fall from her mouth.

The animal continued to walk the length of his grief.

“You are in so much pain. So much pain ever since you were a child. Remember that pain? You want to forget that pain. Oh, that guilt. Remember the guilt? Was it your fault? Was it your fault that she beat you? Poor boy. Was it your fault that you beat him? Poor man.”

It stepped into his ear, wove its return into the dark tunnel of his consciousness, where it belonged. Where it was born.

“You’re just like her.”

“No. No! I’m different. It was an accident! I’m not her. I didn’t break his wrist on purpose. I just grabbed him wrong. It was a mistake. Namibia knows that. Menelik, babyboy, he must know that his daddy, that I, didn’t mean ta—”

“You refuse!” the animal thundered. “You must not refuse your truth, Ishmael. Now is not a time for liesss. Look! Look at yourself! You broke him. The broken break. Who are you that breaks?”

Ishmael dry heaved and wept.

“But I love him so much.”

“Look!”

“I didn’t mean to!”

“Liar!” Its body swelled into a pulsing mass, filling his head with an insufferable pressure.

Ishmael shrunk to a whisper. He placed a thumb in his mouth. “Hm, broken wrist ain’t shit though is it? Ain’t nothin really. That boy don’t know pain. Real pain. Bruises. Bite marks. Scratches. Grow the fuck up. He don’t know shit.” He groaned and shivered. “Help me! Somebody! Jamal? Jamal! Why won’t you help me? Please don’t leave me with her. Mama, no, stop! Stop! STOP—”

“Ishmael!” The wife shouted, slamming her fist against the divider.

He gasped, a man drowning.

The world returned, startling and sharp.

He looked up. The wife stood at a distance. He saw the gaping, ineffable fear in her eyes. They were black and without shine. They compelled him to stand. He swayed on his feet.

“It was an accident,” he said. “Don’t call the ambulance.”

“Eh wuhn ax in cah mboo lant,” she’d heard and Ishmael mistook her stillness for understanding.

He snatched a plastic bag from beneath the counter and pressed it to his wound.

He stumbled past the too quiet wife, careful not to touch her.

He dragged his body home in that unbearable heat. Six blocks.

All the while forgetting what he knew.

He didn’t have a mind to answer with. His mouth too destroyed to hold language.

He lay on their bed, face split to the pink flesh. A soft, tender-swollen from forehead to chin, grazing the left eye, turning the whites. She had to look at him, smelling that smell that belonged to the unseen, the inside, because he refused to go to the hospital. He writhed, screamed with his too wide mouth, then fainted. She thanked God their son wasn’t home. She sewed him shut with a needle she used to mend denim, swallowing bile as she punctured inflamed skin. She watched his unflinching sleep between dabs of rubbing alcohol. When he came to, he moaned through the pull of the thread. She wanted to soothe him, but pain like that don’t want company.

0

For weeks, Ishmael lay on his back, staring down at his feet because he couldn’t look anywhere else—crying. The salt from his tears reminded him he was alive; his sobs rattled in his chest like triumphant laughter. Delirious from self-pity. Or fear. He’d seen it again. No, but he couldn’t have. There was nothing to see.

1

Menelik had nightmares about a man sitting in black, surrounded by black, cackling until tears welled in his six jaundiced eyes. He woke in terror, ears faintly ringing. He missed his daddy. In spite of what his daddy had done. No doubt that cryinglaughing man had something to do with him being gone. What else could be so funny? The secret he kept tickled him pink.

“Mama,” Menelik came running into the living room late at night, already bent on weeping. He shook her shoulders until she pulled him onto the couch. Draped her arm over his thrashing heart.

Weightless in sleep, Namibia told babyboy what nightmares are: longing churned into a spell, opening portals for fears to crawl out. You have to be brave. Can you? I shouldn’t ask you to. You shouldn't know a world to be brave for.

2

Namibia didn’t want Menelik, or anyone, to see Ish. Not until he had eyes and a mouth and a mind.

Ish would want it that way. She was sure of it.

But people started to ask where he was.

He can’t miss this much work, Namibia. He can’t. There’re people out here, young idle kids, waiting! for something to do. Now, I gave Ish a job, because I know his people. Been known his people. But at the end of the day, baby, I run a biznuss and his people is dead. He better be in tomorrow or that’s it, girl. That’s it.

When tomorrow came and Ish did not, she went to the store to plead with that greedy man. She stepped into his poorly lit mini-mart. Nobody ought to be scrambling to work in this shit hole.

Under the fluorescent lights, between the canned foods and the dry ones, she spoke softly to him. She knew she had pretty, convincing eyes. They were slits in her head, but when she fixed her pupil on another, that body was hers until she said all she had to say.

“What’s happened to him?”

“Well Mr. William—he’s ill.”

“Well I know dat much! When my wife got home, she said he was talkin to himself, told me there was blood, and that he’d thrown up too! We had to bring the cleaners in off schedule. Cost us a fuckin’ dime. That’ll have to come outta his next check but we can talk about that later. What I wanna know is: What kinda sickness make you act like that! Sheesh. He scared my wife. He been ill for three, fo’ weeks! What kinda sickness he got?”

He was concerned for himself. His safety. Any man that’s been sick for that long has got to have caught his death. Namibia kept talking, circumventing his questions with neutrality, uncertainty, hopefulness, and he kept listening, assuaged by the frail, crisp sound of her voice. But he had already made up his mind. He won’t fire the boy. No need to. He’d just wait for the news of his death to reach him in the coming days, then pick one of those curb-sitting men to mop for nothing. No reason to give Namibia more heartache than she could take anyhow.

“Ish.”

She appeared at his side, smiling a little. Something had gone right today. If—when Ish got better, he could pick up where he’d left off. To have his job back would be good. Plain good. Show him how normal things still were. How ready normal was to have him. She’d keep the news to herself. Tell him when it mattered.

Ish, who could now turn his head and speak when hydrated, looked at her. She loved him, in spite of what he had become.

His voice a broken stream of breath, he often spoke nonsense.

“Name.”

She didn’t like how his face looked. Two jigsaw pieces struggling to fit together. She fixated on the parts of Ish’s skin that remained the color of fresh things changing season to stave off the hot twisting and knotting in the back of her throat.

He used to be a handsome man.

“Name…I….saw.”

If she wanted to see that man again, she’d have to look at her son. She had already begun searching for him in the child’s face especially while he slept. He took her eyes but Ish’s complexion. Took his hair, but her hands. It became a game on nights when she couldn’t find the peace to sleep.

She stared at the space above Ish’s right eye.

“Yell….ow.”

She nodded and shook two pills out of the bottle. Amoxicillin. Originally for a urinary tract infection that had healed on its own. She’d figured they could help him. This was the reason she’d come into his room: to give him her antibiotics. Otherwise, she occupied the living room, where she slept to avoid the sound of suffering, where she sat for what felt like hours glaring at her reflection stretched across the blank television screen. In the silence, she starved her desire for answers.

(What did her son think of her? When had Ishmael lost himself? Who had taken half his face? Would they come for his family too? Was this their end? Was it best to just—go? You can’t leave a sick man.)

“…saw.”

She sat on the edge of the mattress now. She picked up the lukewarm water on the bedside table and angled the straw toward his twitching mouth.

“Yellow.” Ish lifted a finger. Pointing.

“That’s enough.” She pinched a pill. “Rest now.”

3

Was he in pieces? The animal Ishmael tried not to look at told him that he was. And apologized for it.

He didn’t want to admit that he believed what the animal had to say. He didn’t want to feel the urge to respond to an apology that should not exist.

He was like this because of something he’d done. He must have fallen. Hit his head. Nothing makebelieve had done this to him.

Ishmael needed to see himself. He wanted to see himself to disprove the animal and stop the horrific visions of raw dismemberment. He knew he was healing, because he could drink from a straw. There was the stab of his jaw, throat, and lips as they flexed and pushed to gain control of liquid and sometimes solids, but behind this sensation was the pulse of regeneration. It swallowed him. A heartbeat trapped in his head, bleeding into his sense of self. When left to that throbbing, he’d start to think about what it meant.

Name had refused his request for a mirror, though. She clearly didn’t understand the need to see oneself whole. He needed his son to bring it.

The emotions he felt at the sight of Menelik were too intense for regular visiting. The first few times, he’d bled and sobbed into the stitches that Name so meticulously refreshed with aloe. After a while, she only let babyboy into the bedroom once a week; early in the morning when the cool air and immobility kneaded the swelling down to lumpy blemishes he could see over. Usually, around that time, Namibia showered and dressed for work. He’d have to talk to Menelik then. He’d have to tell him to bring something. A mirror, a spoon, a laptop screen. It didn’t matter. Just bring it.

4

Cause Ish won’t dyin’ soon enough, the greedy man fired him. He called Namibia at seven-thirty in the morning and said, when the boy gets well, he don’t need to worry bout comin’ in here. She sighed into the receiver, Fuck you.

She listened to his insults while undoing her satin headscarf and stepping out of her house dress. As if she’d never been called a blackbitch befo’.

5

Before William called to break their family into smaller pieces, Menelik shuffled into the room with his eyes on the carpet. He made it to his father’s side like that. Head down, eyes tracking the lint in the carpet fibers. He saw an ant. Small and black traveling across mounds of mute, beige landscape.

Where was it going? Where had it come from? How far was its home? There was no home here.

His mother had cut his hair the night before. The skin behind his ears burned. He used his thumb to press on where it hurt the most. The pressure somehow relieved the pain.

He wanted to have long hair like the girls in his class who took combs out at lunch and let the teeth glide through. The sun seemed to shine on those girls.

He didn’t have nightmares anymore, but his mother’s empty eyes, his daddy’s closed ones, they chilled him to the bone. And it seemed that all the rooms in their apartment never turned bright anymore, even with the lights on. Made him wonder where brightness truly came from.

Either way, Menelik wished for a little more sun to fall on him.

In his hand, he held a pocket mirror that he’d taken from his mama’s purse. It was gold with a sticker on the back: Balmain. He called it Ball Man. He’d taken it for himself a while ago. He liked that it looked like the sun. His mama once asked him if he’d seen it and he said, No, never. At the playground, while his classmates hollered on the jungle gym and leaped off of swings mid-sky, he stared into his own eyes. Would he turn mean like his daddy one day? Was meanness something you could find or see before it came and claimed you?

6

Ishmael stared at Menelik’s oiled scalp. He wanted to put his nose against it. Let the tea tree oil burn the inside of his nostrils, get into his wounds and burn them too.

Before Ishmael became what he was now, Menelik would stare into his father’s eyes with such intent it made him question the purpose of sight. He’d stare into his father’s eyes as if he needed to find something truer hidden behind that unconvincing sheen of knowing. He stared at Ishmael looking for what his father wouldn’t say, couldn’t say, didn’t know should be said about being his son, the son of a son. Waiting for him to admit to his own ignorance, perhaps. For him to confess his failure to do anything more than mimic the bonds that replayed before him as a child. He was not a creator, after all. A pattern following a pattern at best.

Now, Menelik seemed more fascinated by the rug than by his own daddy, his own incredulous fate. Ishmael was seeing scalp. This was his mirror.

The animal stepped forward.

Ishmael flinched.

Its shadow stretched through the boy’s body.

“I am so sorry.”

7

Namibia stood in the hallway in a shower cap with a towel wrapped around her damp skin, trying to remember what she needed to do next. William’s call had thrown her more than she was willing to admit.

Menelik came out of his father’s room with dry eyes. He walked past her with something shiny glinting in his palm. Was that her damn—?

“Daddy is crying.”

She watched him disappear into his bedroom. His impassivity a concealed dagger held down by his side. She bit the inside of her cheek, missing his bad dreams, times when his fear reminded her of innocence, of fresh malleable life. She should have never told him about bravery. She should have let him cry into her arms for as long as he needed.

8

Menelik had a bunk bed even though he was an only child. He used the top bunk to hide his thoughts. His journal was tucked beneath the second mattress with his pen. He climbed up the ladder, pulled out his journal, and swung his legs off the side of the bed. Yesterday he didn’t have much to say. He described an incident in class when he’d yelled at Brendan for calling somebody’s mama a hoe who licked clits for two pennies. For some reason, it felt like Brendan had really been talking to him. He put his pencil on the paper, but the words wouldn’t come. He needed them to. He waited. He flipped through his journal, kicking his legs faster and faster.

Months ago, on his eighth birthday, his daddy broke his wrist. The pain was unlike anything he’d experienced. It reminded him of nothing and birthed a solitude that lived at the base of his neck.

Daddy had never done anything like that before. Never say never, Mrs. Pedington says. I’ll never like the color blue. Never say never. I’ll never play with you. Never say never. I’ll never hurt you again. It was an accident. Something to do with him playing with his toys in the living room and not cleaning them up. Something to do with him not listening. Daddy hugged him in the hospital when Mama told the doctor that he’d fallen off his bike. They must have looked like a family.

“Promise me you’ll be careful next time,” the doctor held out a red lollipop, like he was some kind of baby, “you’re a brave boy.”

“I’ll be careful,” Menelik said. “I won’t fall again.”

In the hospital parking lot, he dropped the candy behind a tire.

That day, he’d only written that his wrist was broken—he had a cast to draw pictures on now.

He flipped back to an empty page. He put his pencil on the page. He wrote the letter “I” then threw the journal across the room. It smacked against the wall. He liked the sound. He threw the pencil. It bounced back and landed mutedly on the carpet. He needed more. He held the pocket mirror in his hand. He grimaced at his wavy reflection in the gold. He felt something in his stomach drop as if he were in a car going too fast over and down hills. So fast the trees outside the windows blurred. The mirror popped and shattered. He hadn’t even felt himself throw it.

9

Ishmael was the kind of man that understood beauty, and so loved to see it. When he was a child, he saw it without looking for it and knew what to call it. God. The soft, black shadow between teeth that could only be seen when Mama’s joy overshadowed the weight of a man’s absence. The dust dance does when the sun shines through dirty kitchen windows and bedroom curtains sullied by absentmindedness. A Black girl’s brown eyes when she looked at her own figure.

He remembered when he first saw it in himself. It wasn’t like Always. His eyes never rested upon himself like it rested upon the world around him. It wasn’t like it was always there. He had to look for it. Especially after his mama was finished with him.

First it was his hands. He’d stare at them against the textures of the universe, intrigued, thrilled by their softness. Then his teeth. White, straight. He didn’t need braces like some kids. His eyes. They weren’t hazel like Jamal’s, but they had their own light. Not simply a light’s reflection. No, it didn’t mimic. The light was inside, behind. A girl he once knew called it a twinkle. He gotsuh twinkle in his eye. Name, when she saw it, called it hers. She was fourteen, looking into his face like he looked into things he cared to know, and said softly after a brief, playful hum: that’s mines.

Not like this happened all at once. Not like he loved himself all at once. Saw that beauty some loved him for by the day’s end. No. It took years. Even years after Name’s hum. But once he had it, he’d curled his fingers around its neck, so tight. So tight. Nearly cutting its breath so that it lay still in his heart and his mind, unchallenged because it was so harmless. And now his son couldn’t look at him.

And now, he was left alone with it. His broken mouth quivered.

“What are you? What have you done?”

The animal showed its teeth as if to say this is what I am, this is what I do.

“You should not have to ask. I belong to you.” It did not smile yet its growl rolled like pleasure. “You summoned me with a broken wrist. Here, look.”

Its many silken limbs melded into one small child’s: a little brown arm with a lump where there shouldn’t be.

Ishmael averted his eyes, sucked in a panicked breath.

The animal snickered. “Why won’t you look? Aren’t you proud of me?”

“Please don’t hurt me anymore. Don’t ruin me.”

“I am sorry,” it whined. “I must show. You must look. I only want to help.”

Ishmael began to cry. “Leave.”

It stretched long and thin and jagged, released a tremorous hiss.

“So soon?”

“Yes. Please. Please.”

“I told you how!” Wet, dark eyes swam in the sea of its body, all relentlessly staring. “You try to forget me and now you don’t know the way out! Remember me, Ishmael. All of me, Ishmael. It will be painful,” its teeth shone crescent moons, “you’ll find what you’re looking for.”

10

The day Menelik had his cast removed, the heat peaked and lit sparks in people’s subconscious minds. Ishmael was at work, unblemished and whole, feeling the full spectrum of his personality. He was gorgeous. He was not. He was confident. He was not. He was hard-working. He was not. He was charming. He was not. He was floating and yet ever present. These sort of fits only happened when he smoked too much. And although he had tried to control himself that morning, the thought of spending eight hours in William’s shop made him incredibly sad. So sad that Namibia had even noticed a certain intensity in his morning routine. The way he brushed his teeth so loudly she wondered if his gums were bleeding a little.

He wanted to call Namibia. They weren’t as good as they used to be, since the accident with Menelik’s wrist, but her voice would still ground him. And a part of her would be happy to hear from him. He was sure of it.

He reached into his pocket and felt for his cell phone. It wasn’t there. He searched in his backpack. It wasn’t there. Alarmed, but not desiring the anxiety of being alarmed, he sat back down and decided it was not meant to be. He was not supposed to call Name. But he thought of her perky, earth-toned breasts like young yams and rested into the image. Lost in a dream sequence of brown bodies in motion, he had not noticed the fog on the acrylic divider. “You miss me?” Suddenly his insides spun and heaved; vomit singed his tongue. His eyes couldn’t grasp the world he belonged to. Because if so then what was that? What was that? that that that what was—he collapsed onto the concrete floor.

11

From where she stood in the hallway, Namibia heard what could have been the drone of prayer. (Her father kneeling with his ninety-ninth reverence pinched between knuckle and breath.) She moved toward their bedroom door. She pressed her ear against the wood—daddy? She clutched her towel to her body. From inside:

“Noooooo I don’t want to remember you. There has to be another way.”

“I don’t want to remember you.”

“I don’t want to remember you.”

Who was Ish talking to? Who was he talking about?

She gripped the door handle. Left her hand there until the metal warmed.

12

At eight years old, Ishmael stands on the potty training toilet that nobody uses anymore, except his big brother Jamal who, when he thinks no one is watching, places it beneath cabinets to reach snacks at night.

Up high, Ishmael notices the flushed skin on his neck. He touches the half moons on his throat. He can see blood pearling on his chin and forehead. He can see the color red blanketing the white in his left eye.

He never knew he could look like this.

Like nobody.

He leans forward over the sink, nose nearly touching the glass, and turns his face in the light. To see this new nobody better.

He thinks it's his own breath fogging the mirror.

Slender, yellow tendrils the length of his torso curl around his shoulder, graceful and firm.

“Did you make her hurt you? You should be kinder to your mother.”

13

Namibia found a bead of strength in her wrist. She pushed their bedroom door open. Her towel unraveled from around her, fell to her ankles.

Ishmael was on the floor, as if he’d attempted to crawl to the door and had failed.

Tangled in bedsheets, he beat his head with a fist, his face coming apart:

“I don’t want to remember you.”

“I don’t want to remember you.”

Breathless now. “I have to.”

He sobbed. “I have to.”

14

Before Lidia stopped by her husband’s store to help herself to a pack of cigarettes and an Arnold Palmer and found Ishmael in his own blood and vomit. Before Ishmael woke in his own blood and vomit. Before Ishmael had fallen, he’d seen an animal that was too frightening to call familiar. Its breath fogged the acrylic divider. Two perfect wet circles expanding, contracting, expanding. Rivulets of moisture pearled on the hard plastic barrier. In the finite space between exhales, black eyes gleamed like polished eight balls.

The divider between him and it melted, became fondant, hissing with unnatural heat as it collapsed onto the cash register. It pooled over the store’s back room keys, the Fireball and Smirnoff nips, the cellphone he couldn’t find, and singed his unbelieving hands. The moment he jerked away in shock, the animal reached forward, as if to keep him from falling backward, and swiped him across the face.

Ishmael trembled against the concrete.

He pressed his forehead to the floor. He held one hand to the hot-wet of his cheek while the other extended stiffly above and over, protecting and pleading.

“Now feels like a good time,” the animal made itself small. It stood in the fluids crowning Ishmael’s head. “You think all is well, it is not. You think you have been spared, you have not. You believe you deserve to play in a faultless mind, you do not. You are not a child any longer.”

15

Namibia backed into the hallway, closing the door to her husband. She stood naked against the wall, breathing, nostrils flaring, eyes unseeing. She could still hear him on the other side. She ran into the living room and searched her purse. She found her cellphone. She pressed 9-1-1. She couldn’t handle this. Not anymore. The stitches yes, but—Her thumb hovered above the call button. What if they come and make it worse? What if they come and lock him up and never let him out? (Would that be so bad?)

What’s the right choice?

What’s the right choice?

What’s the right--

Menelik screamed. The sound pierced her chest. She dropped the phone, clamped a hand over her mouth.

Where was Ishmael?

Had he?

Could he?

Again?

16

Ishmael falls from the training toilet. Against the bathtub, he hides his eyes as if they were the source of his troubles, clutching them shut against the sound of things everywhere.

He shivers on the floor, muscles cramping as he pulls his body inward to stillness.

The warmth of his own urine, weighing him down at the hips, convinces him he’s safe.

He pushes himself from the porcelain and rests on the bathroom mat. There is only the steady drip of the bathtub faucet and Jamal, standing in the doorway, watching him. Their mother’s screams carry from the living room and Ishmael thinks they’re for him.

Automated clapping. The muffled voice of the television. No—she’s laughing.

“What happened?”

“I saw sumthin.”

“Damn.” Jamal turned nine last month. He is learning to watch people burn. “Whatever it was fucked you up.”

Reluctantly, Ishmael removes his pants and underwear—with the Power Rangers doing athletic jumps around his thighs—and Jamal stands there, smirking.

“Go away.”

Ishmael tells himself not to cry.

“Make me.” Jamal crosses his arms. “Lil boys that piss their pants don’t got no rights.”

Ishmael reaches for a towel and wraps it around his waist. He feels bold.

“How come you don’t get hurt?”

“I don’t know, man.” His brother shrugs.

“You’re lying! You’re a damn liar!”

Ishmael watches his brother squirm. The silence angers him. He jabs a finger.

“Mama don’t like me because I don’t look like you. I look like him.”

Jamal shrugs again. His words have abandoned him.

Ishmael steps into Jamal, shoves him. “You let her! Why you let her!”

Automated clapping. Screamlaughter.

Jamal opens his mouth, a sentence swims in the well of his throat. He snatches it quickly, before it can evade and drown: “What am I supposed to do, Ish?”

They stare at one another. Ishmael doesn’t know the answer. They are only kids and Mama is all they have.

Jamal hesitates, but eventually he allows himself to turn and leave.

Ishmael stands alone, then in the shadow of the animal, whose warm body at his back might be mistaken for a comfort. As its delicate limbs spiral around his chest, thread between his thighs, and twist around his neck, Ishmael hardens into an ancient and implacable rage.

17

Namibia pushed open her son’s door hard enough for it to swing and hit the wall. She didn’t know what she would do if she saw Ish.

She found only Menelik, seated on the top bunk, quiet now.

“Mama,” he said. He stepped down the ladder.

He started to hug her, but pulled back. He rubbed the wrist that clicked when he did things, his face streaked with salt.

She shook her head slowly and grabbed him by the shoulders. She brought him to her. She curled her body around his, willing her limbs into armor. She rocked. She rocked and moaned an almost lullaby. His body swayed and swayed. Her abdomen grew damp where his face and her navel met. She trapped a wail against the roof of her mouth. She had words that she could not speak.

Not yet.

She wasn’t sure when. When he was old enough to forgive. When he was old enough to know that she must ask for his forgiveness.

18

The store’s concrete floors shook and slanted as the animal neared. It touched the hand that Ishmael held against his torn face, stroking the curvature of his pleated skin. Ishmael whimpered, jerked away.

The animal brought its chewed mouth to Ishmael’s ear, the heat of its tongue inches from his skin: “You thought you could make a big happy! faaamily.”

Its voice whipped and crashed like roaring currents; He could not hear the boss’ wife enter.

He did not see the wife peer through the unscathed plastic divider, over the intact register, past the perfectly aligned alcohol nips. He did not see the cigarette fall from her mouth.

The animal continued to walk the length of his grief.

“You are in so much pain. So much pain ever since you were a child. Remember that pain? You want to forget that pain. Oh, that guilt. Remember the guilt? Was it your fault? Was it your fault that she beat you? Poor boy. Was it your fault that you beat him? Poor man.”

It stepped into his ear, wove its return into the dark tunnel of his consciousness, where it belonged. Where it was born.

“You’re just like her.”

“No. No! I’m different. It was an accident! I’m not her. I didn’t break his wrist on purpose. I just grabbed him wrong. It was a mistake. Namibia knows that. Menelik, babyboy, he must know that his daddy, that I, didn’t mean ta—”

“You refuse!” the animal thundered. “You must not refuse your truth, Ishmael. Now is not a time for liesss. Look! Look at yourself! You broke him. The broken break. Who are you that breaks?”

Ishmael dry heaved and wept.

“But I love him so much.”

“Look!”

“I didn’t mean to!”

“Liar!” Its body swelled into a pulsing mass, filling his head with an insufferable pressure.

Ishmael shrunk to a whisper. He placed a thumb in his mouth. “Hm, broken wrist ain’t shit though is it? Ain’t nothin really. That boy don’t know pain. Real pain. Bruises. Bite marks. Scratches. Grow the fuck up. He don’t know shit.” He groaned and shivered. “Help me! Somebody! Jamal? Jamal! Why won’t you help me? Please don’t leave me with her. Mama, no, stop! Stop! STOP—”

“Ishmael!” The wife shouted, slamming her fist against the divider.

He gasped, a man drowning.

The world returned, startling and sharp.

He looked up. The wife stood at a distance. He saw the gaping, ineffable fear in her eyes. They were black and without shine. They compelled him to stand. He swayed on his feet.

“It was an accident,” he said. “Don’t call the ambulance.”

“Eh wuhn ax in cah mboo lant,” she’d heard and Ishmael mistook her stillness for understanding.

He snatched a plastic bag from beneath the counter and pressed it to his wound.

He stumbled past the too quiet wife, careful not to touch her.

He dragged his body home in that unbearable heat. Six blocks.

All the while forgetting what he knew.

akhir ali (she/they) is a queer, Black storyteller and traveler from Washington DC, who is currently pursuing their MFA in Fiction at Sarah Lawrence College. Their work has been published in Autostraddle, Salty, and elsewhere. When they are not eating, they are writing.