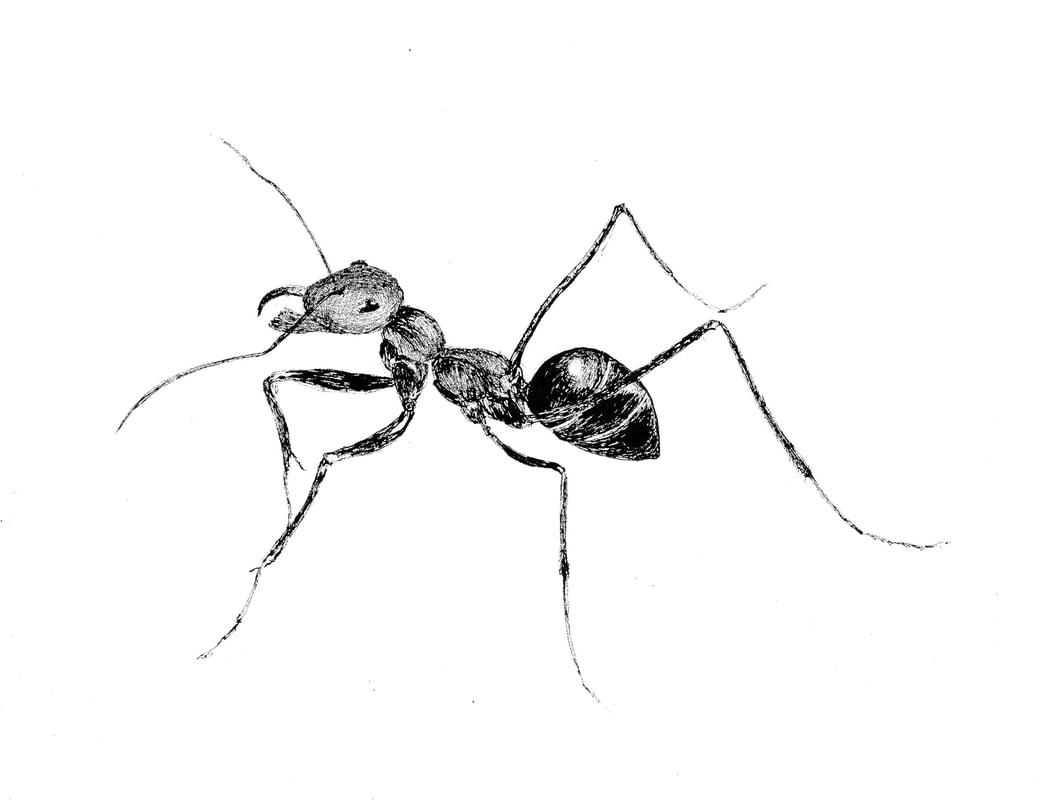

Legs

The ant in question has a jurisdiction that extends no farther than the lower quadrant of a leg from a dead grasshopper. The rest of the grasshopper’s carcass, unbeknownst to the ant, lies only a few inches further afield (though that is neither here nor there). The ant dutifully carries the leg back to its colony. The ant’s only purpose is this purpose. The ant is this purpose. The colony’s gates, however, have just been flung wide by a rabbit’s paw; as a result, one of the ant’s own legs gets stuck in some debris from the displaced mound (it was a makeshift and imperfect structure to begin with). The other ants—their thousand-fold legs incapable of care—trample over their immobile peer until it too is dead and finally is dragged down to the busy depths beneath. That many-legged destiny—the ant’s and the grasshopper’s and the rabbit’s and the other ants’—represents fate at its most miniscule, and yet it is still more miraculous than all of the physics at work in three suns. And you, a pale and partial creature, idle in your chair and with but two idle legs, hope to possess knowledge of that march.

A Footnote on the Baleful Effects of Happiness

In the prologue to his book La vida y el universo (Madrid, 1967), the great Spanish cosmologist Francisco Garrido Fernández, having insisted upon the statistical certainty that extraterrestrial life exists outside of our solar system, asserts nevertheless—though in a mere footnote!—that no such life has ever visited, or ever will visit, the earth. It is a bold speculation, to be sure, though Fernández treats it casually, as though it had the soundness of a purely logical conclusion. Indeed, and as strange as it may seem, I recall that when I first read this footnote I was struck, not so much by its contents as by that very calmness, that matter-of-fact quality of its sure, lucid sentences. Equally strange: that solitary note is all I can still really remember, at least with any degree of vividness, from Fernández’s book—a book which surely contained more than four-hundred pages and which, at least while I was a young and pious student of physics at the University of Barcelona, I held dear to my heart. Most strange of all: I have been unable to locate any existing copy of the volume, and so I must concede straightaway that it could have been one of those rare books that exist only in dreams (and what, then, of Fernández himself, did I dream him too?). The footnote, however, continues to stand out in my memory (I can see it, even now, there on the page, in such small and unassuming type). It remains vivid, I believe, because of the unusual principle it expressed, namely, that too much happiness can have negative effects upon the development of science. So compelling did I find this argument at the time that I even translated the note into English, word for word, in a private journal of mine—one that I only today rediscovered (it was perched high on a shelf in a closet full of other dusty and personal artifacts). Here then is that note, which may have come from a dream, but which even now reads well to me:

No alien life has ever visited our planet. Nor will it ever. We can be assured of this for the following reason: long before any intelligent species could possibly figure out how to solve the daunting problems of interstellar space travel, it almost certainly will already have conquered the much-simpler mysteries of happiness. And the latter achievement obviates the former one. This will be our destiny as well: the pleasure-centers in our brains, all the organs of inner peace and satisfaction, the optimal ratios of dopamine and other neurotransmitters in the basal ganglia, indeed every biological facet of happiness (from bristling skin cells to slightly-thinned blood to the mild rush of warmth in the face)—all of these, long before our ships can reach the speed of light, will fall under our complete control. The construction of happiness will be then as rudimentary a process as pain-relief is to us now: it will be as easy as swallowing a pill. And I don’t mean drunkenness, or any sort of intoxication; I mean genuine happiness (or a dead ringer for it anyway). And if you’re happy—if you’re already at peace with your existence and with the world and with the sky over your head—then why on earth would you bother trying to reach that distant star? |

At the bottom of that page in my journal, separated from the text quoted above by several empty lines, I now read the following two sentences, which I do not remember writing; whether they are my own, or belong to Fernández (or to someone else entirely, or to a dream), I may never know:

We may reduce these reflections—I have done so, at any rate—to the following rule: There’s not a boon in all the universe, not even happiness, not even goodness itself, which is always and only good. |

A. Joachim Glage lives and writes in Colorado, where he enjoys no longer being an attorney. He received an M.A. in English Literature from the University of Virginia, before completing his graduate work on literary and aesthetic theory at the Literature Program at Duke. He earned his law degree from New York University School of Law. Other fiction by him has appeared recently or is soon forthcoming in such periodicals as The Georgia Review, Litmag, The Collagist, DIAGRAM, Santa Monica Review, Philosophy and Literature, and others.