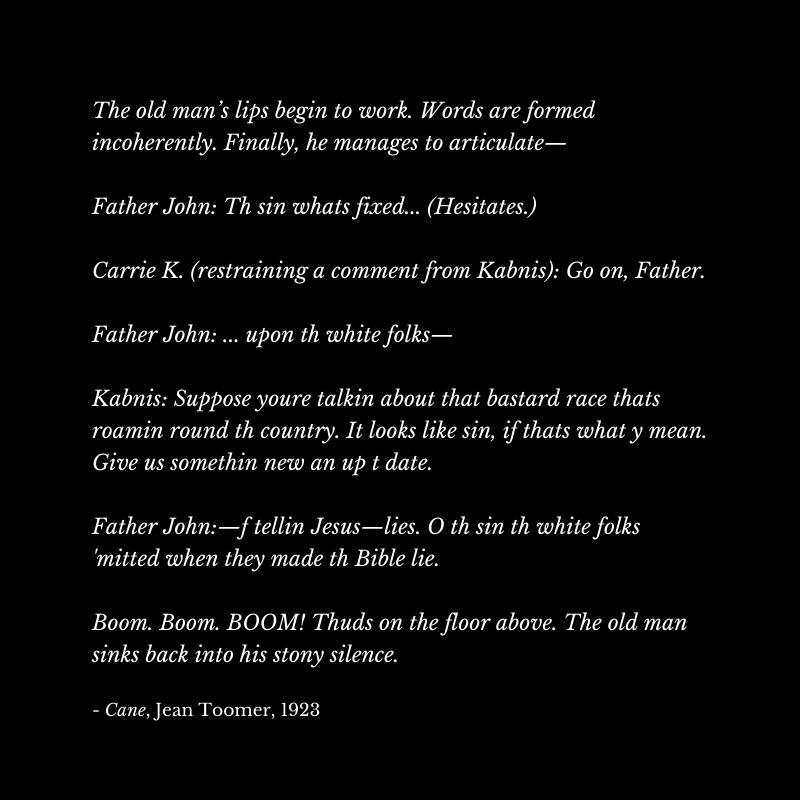

Author's note: The novel excerpted below is a pastiche of Jean Toomer's (1923) "Cane", which was set in the rural Southern community in which the landowners' small cane fields were the setting for all manners of drama and passion and human interaction. My retelling of "Cane" resurrects, among other things, Toomer's many characters who died in the cane and gives life to one very minor, but compelling character most frequently referred to as “the Old Man.” Readers know little of the old man other than what the other characters project on to him during about a dozen conjectures about his life throughout the course of the book. All we really know of the Old Man is that he sits in the corner of the basement of a wheelwright’s shop, and that he is fed by a little girl. He speaks just once, giving a brief but eloquent pronouncement of guilt on the area's plantation elite. He is described as being deaf and blind and immobile, but I don’t know about that last part. He captivated me, and I came to believe in his mobility. I hope you enjoy the way I put him in motion. |

He is like a bust in black walnut. Gray-bearded. Gray haired. Immobile. … The only word he says is sin.

—Toomer, 1923

—Toomer, 1923

Barlo stood back, knowing that the old man, for the moment, was off again in spirit. He leaned in and tied a blue satin scarf around his neck. He could see that the old man’s face was serene.

The old man, the houngan, was out of his body, free from its humiliations and constraints, flying above the pine and assessing the crossroads, the cotton, and the cane. The town stood small but erect in the midst of the pastoral calm. All was as it usually was at dusk. Deer lay down on soft needles along the pine forest’s edge, or sniffed the wind and ambled along the line of trees. A family of warblers nested in a tree nearby, and a blackbird took to flight from the forest across from the Limons’ break of cane.

The old man, the houngan, was out of his body, free from its humiliations and constraints, flying above the pine and assessing the crossroads, the cotton, and the cane. The town stood small but erect in the midst of the pastoral calm. All was as it usually was at dusk. Deer lay down on soft needles along the pine forest’s edge, or sniffed the wind and ambled along the line of trees. A family of warblers nested in a tree nearby, and a blackbird took to flight from the forest across from the Limons’ break of cane.

Mame Lamkin’s husband had wandered out to the forest’s edge past the animals. The year that had passed between his murder and the moment of the old man’s flight had not seemed to change him at all save for the wispy thinness of a dead-self in limbo that had replaced the manly flesh in which he had once lived. He swayed against the wind current, looking down on his mangled midsection in agonized translucence. His eyes hung down, no longer looking for the vigilantes who had dismembered him, nor his lily-White lover who had sat in her house and chewed her nails—tellingly—while the buzzards plucked at the Black flesh to which she’d once clung. He sensed the old man, and lifted his empty, invisible eye sockets to the moon. The old man moved beyond the ghost and his sorrow.

At the crossroads, the old man saw Becky, ethereally unearthed from the rubble of her cabin, waiting for her sons to come home. He saw Bob Stone holding his neck as if he wanted to stop the blood, though the blood had stopped running many months ago, hours after Tom Burwell’s blade had slid across it in Bob’s own patch of cane. Bob and Becky—these prematurely dead in their individual levels of limbo—hovered nearly on top of each other. But neither of them knew that the other was there. They swayed and searched and wondered, only somewhat aware that they existed in a space from which they could neither escape nor return to their lives. A long-tailed weasel burrowed in the earth underneath them.

Too many sorrowful spirits and too much unjust blood hung around the fields and forests of Sempter. When he flew too low, too close to it all, the disembodied old man choked with sorrow, like the fist that is the past will do to a man, and brought the days before the end of slavery up from his core. His memories of the sugar mill and the bell rack and the scent of cane syrup mixed with burnt human flesh were threatening to pull him down, so he lifted high up above it, to the line of tree tops that only the black birds could see. He made a swift but thorough pass through the fields of the Limon family; their land extended as far as the old man could see, over hills and into valleys, beyond the beyond and back.

From the distance at which the old man flew, the earth appeared to be perfect. It was green. Breezy. Free from its history and its reality, the earth was the picture of peace. Besides the stranded spirits and the scattered animals, no one was nearby. Behind him were the pine trees, the road that edged along them, and the wheelwright’s workshop where the ceremony to feed and honor the obviously angry loa would go on.

Off to the old man’s side just beyond the limit of his vision was the compound begun by his Barlo, which the old man knew he may not even live to see completed. But that didn’t matter much to him anyway. The compound was Barlo’s project. His was simply getting through this life.

In front of the flying old man was acre upon acre of land, reminding him of time and the place that he’d grown from infancy and slavery into freedom and manhood. He turned and sent himself down the hill toward his right. He passed a bobcat on a rock and came to the Sempter crossroads. To its left was a cluster of Creek family homes—a small community that the Negroes aptly called The Left-Overs. A “half-breed” moved down the road toward the door of one of The Left-Overs homes. The half-breed flinched as though he wanted to acknowledge the old man, but instead covered his head and kept moving. The old man free-fell down the air some to see the man, but stayed a respectful distance away and kept on going his own way. He careened above some sleeping geese in the rotting tree swamp, then turned and emerged in the midst of the cluster of shanties beyond.

At the crossroads, the old man saw Becky, ethereally unearthed from the rubble of her cabin, waiting for her sons to come home. He saw Bob Stone holding his neck as if he wanted to stop the blood, though the blood had stopped running many months ago, hours after Tom Burwell’s blade had slid across it in Bob’s own patch of cane. Bob and Becky—these prematurely dead in their individual levels of limbo—hovered nearly on top of each other. But neither of them knew that the other was there. They swayed and searched and wondered, only somewhat aware that they existed in a space from which they could neither escape nor return to their lives. A long-tailed weasel burrowed in the earth underneath them.

Too many sorrowful spirits and too much unjust blood hung around the fields and forests of Sempter. When he flew too low, too close to it all, the disembodied old man choked with sorrow, like the fist that is the past will do to a man, and brought the days before the end of slavery up from his core. His memories of the sugar mill and the bell rack and the scent of cane syrup mixed with burnt human flesh were threatening to pull him down, so he lifted high up above it, to the line of tree tops that only the black birds could see. He made a swift but thorough pass through the fields of the Limon family; their land extended as far as the old man could see, over hills and into valleys, beyond the beyond and back.

From the distance at which the old man flew, the earth appeared to be perfect. It was green. Breezy. Free from its history and its reality, the earth was the picture of peace. Besides the stranded spirits and the scattered animals, no one was nearby. Behind him were the pine trees, the road that edged along them, and the wheelwright’s workshop where the ceremony to feed and honor the obviously angry loa would go on.

Off to the old man’s side just beyond the limit of his vision was the compound begun by his Barlo, which the old man knew he may not even live to see completed. But that didn’t matter much to him anyway. The compound was Barlo’s project. His was simply getting through this life.

In front of the flying old man was acre upon acre of land, reminding him of time and the place that he’d grown from infancy and slavery into freedom and manhood. He turned and sent himself down the hill toward his right. He passed a bobcat on a rock and came to the Sempter crossroads. To its left was a cluster of Creek family homes—a small community that the Negroes aptly called The Left-Overs. A “half-breed” moved down the road toward the door of one of The Left-Overs homes. The half-breed flinched as though he wanted to acknowledge the old man, but instead covered his head and kept moving. The old man free-fell down the air some to see the man, but stayed a respectful distance away and kept on going his own way. He careened above some sleeping geese in the rotting tree swamp, then turned and emerged in the midst of the cluster of shanties beyond.

The guard of the Negro quarters, whom they no longer called the overseer, oversaw the activities of the cluster of shanties from his raised brick one-room wood house with the rickety porch. He sat there with the lamp on, and he listened. The Negro yards were empty and quiet, and most of its lamp lights were out. The old man knew that the sheriff had told the guard to keep the Black folk in tonight, so the old man passed the shanties and the shack of the guard as well. He couldn’t stand the scent of the blood on that man’s hands, and so he stayed away from it and thus away from his own rage. He engaged himself in the mission of his flight.

He saw the Sempter chapel, but knew he couldn’t get close. It wasn’t the column of buzzards that kept him away, but the impenetrable protection all around the building that would bounce the man off like a ball. He came across the quarters to the front Big House instead. The audacious antebellum mansion glowed in the red moonlight and appeared to him as a pinkish familiar place. It welcomed him weirdly toward its insides. The magnolias had just begun to bloom, so he allowed their scent to guide him toward the mansion’s iron gate. He saw its sign, down in front, and knew, from years of working there for free and then for pocket change on the dollar, that the name of the place was painted on the sign’s face. Tempus Plantandi, it said—what the Limon family called their old family home.

Each of the second floor windows above the pillared porch of Plantandi was open just a bit, and he chose the one just to the right of center to go through into the house. Once in, he found the mistress, Young Dave’s wife, unmoving, anesthetized from those of Barlo’s herbs Old Chromo had cooked into her cobbler. Ol’ Massa Dave’s wife, the withered Mistress Limon, slept stone still in her ancient Victorian bedclothes and four-poster Victorian bed in the master bedroom down the stately hall. A servant reclined in a rocking chair in the corner of the room, sleeping lightly and dreaming of 4 different-colored horses. She whispered something and clasped the cross that hung around her neck as the old man passed in spirit and kept on going.

He saw the Sempter chapel, but knew he couldn’t get close. It wasn’t the column of buzzards that kept him away, but the impenetrable protection all around the building that would bounce the man off like a ball. He came across the quarters to the front Big House instead. The audacious antebellum mansion glowed in the red moonlight and appeared to him as a pinkish familiar place. It welcomed him weirdly toward its insides. The magnolias had just begun to bloom, so he allowed their scent to guide him toward the mansion’s iron gate. He saw its sign, down in front, and knew, from years of working there for free and then for pocket change on the dollar, that the name of the place was painted on the sign’s face. Tempus Plantandi, it said—what the Limon family called their old family home.

Each of the second floor windows above the pillared porch of Plantandi was open just a bit, and he chose the one just to the right of center to go through into the house. Once in, he found the mistress, Young Dave’s wife, unmoving, anesthetized from those of Barlo’s herbs Old Chromo had cooked into her cobbler. Ol’ Massa Dave’s wife, the withered Mistress Limon, slept stone still in her ancient Victorian bedclothes and four-poster Victorian bed in the master bedroom down the stately hall. A servant reclined in a rocking chair in the corner of the room, sleeping lightly and dreaming of 4 different-colored horses. She whispered something and clasped the cross that hung around her neck as the old man passed in spirit and kept on going.

There were vases and chaises and mirrors and bureaus and carpets and cupboards and dishes and silver and doilies and curtains and covers and photos and paintings and gadgets and statues and more of the trappings of particularity and excessive wealth within the mansion around him. The stretched, framed, and hung needlepoint on the wall read, in fancy script, “Reap the harvest of your land. —Leviticus.” But the old man couldn’t read it. His eyes were back in body, they were blind anyhow, and had never beheld the grammar books and readers the Big House children sat on the porch and read. He swept right past the cross-stitched directive and the myriad heirlooms, pleased with how disinterested he was in the meaningless items that mattered so much to this upright old family. He had coveted their stuff in slavery days when he was young himself. But none of it seemed to matter at this moment. He was freer than emancipated. He had no use for anything, nothing but the fresh food that the girl from the Big House brought him, the rhythm of the drums, his tall wooden staff from the Motherland, the rattle of the ascon, and the prayer chants of his godson and flight and dreams and Mother Africa—his homeland, his ‘Nan Ginee—where he would surely go as soon as his worn-out body gave up on him and released him once and for all. Soon his body wouldn’t matter, and heirlooms and items would be worthless things of the past.

Sarah T. is a poet and spoken word performer who has stood before many a mic and podium saying many things. Her first book, "This Past Was Waiting for Me", is a collection of poetry and epistolic prose that explores the manner in which the past—especially America’s colonial past and the race-class hierarchies that it established—plays out in the present. It is due out this Spring. The above excerpt of her novel-in-progress--Deep Rooted Cane—evolved out of work she did as a creative writing fellow at Hambidge Center for the Arts in Rabun Gap, Georgia.

Sarah T. is also Sarah J. Trembath, a graduate of Temple and Howard universities and an American University writing instructor. Her scholarship has appeared in Everyday Feminism and Radical Teacher. She lives in Anacostia, SE, DC with her husband and son.