Chapter 1: Disgrace

‘There are many ways to skin a cat: sir.’

‘Are there really?’

‘Yes; there are.’

It was a tad embarrassing – this situation: hanged, drawn, quartered. The long dangly older man – sporting a large bald head like a waxen, yellow-pink bowling ball, and dressed in clean-pressed black trousers and pristine white shirt, opened widely at the collar – was also feeling slightly embarrassed. It just wouldn’t do – this pornography business. For all the young man opposite being one of his favorites – house rules were house rules; one shouldn’t, one mustn’t let the team down; a gentleman owed it, as it were, to his club.

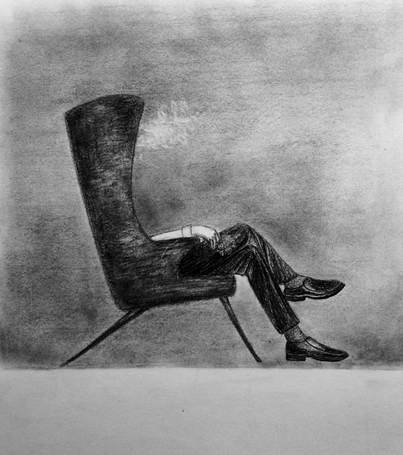

They were seated over ten feet apart; the distance was both studied, and studious. The wide oval-shaped room, a grand Don’s study, was lit this afternoon by only the one large window at the farther side; though fitted with lamps, by choice they were only rarely put to use. This dark and smoldering bear-like-cave, this book-lined lair evoked auras of burgundy and of sepia and of oak – wine-colored comfort from a different, less-rushed eon. The Don in question sat at the farther end, just beside the sole window of that monkish keep, in a low and fatly-cushioned armchair, wine-toned, too; his long and spindly legs were crossed over each other, rather effeminately, as he toked occasionally on a white-tipped cigarette. The student facing him, seated on a lime-grey couch, was hunched forward over himself and over the small square table that lay just in front – ashtrays out-laid there, too. But the younger party at this parley didn’t smoke; or had chosen not to: in this scenario.

‘The fine will be fifty pounds: sterling,’ the older man now said.

‘That’s fine.’ Omar Ghaleez grinned from ear to ear, inanely delighted at the sight of his near-bumbling, now-scandalized interlocutor.

‘Stop that!’ He exhaled a long lungful of smoke, a small hint of in-sufferance and disdain about his reed-thin lips.

‘What?’

‘That smirking,’ he said. ‘It’s: smug.’

Omar Ghaleez stopped his rictus; and not because it was requested. No; it was the adjective, “smug” that had done it. “Smug” was the operative culprit. It was, in truth, an effortlessly beautiful word. But a word, also, and at the same time, he hated. And the love and the hatred formed a taut and poignant antagonism in his mind, presently. He’d often been dubbed: “smug.”

It was a kind of “grace,” he now supposed to himself – smugness, that is. Yes: something a philosopher had written by the wayside spurred and suggested the analogy to him. Said philosopher had written of grace, tangentially, as a, or the, great equalizer of or in human behavior. To be “grace-ful” was to be susceptible to posthumous (poetic?) justice; was to forge good, straight timber – after the fact – from splinters and orphaned shards. Hypocrisy, say, or syncretism in self and/or world, when smoothed-out, styled (if retroactively) was a way of understanding what grace just was. Whether we meant a clumsy individual’s faux pas followed by its imminent redemption in a face-saving jest, or, the action, say, of the Holy Spirit retroactively justifying and in-jigging contradictory dogmas as the visible body of the Church changed tacks in its scuttling development – either way: grace was the processed outcome, the working upshot. Smugness, by turns, was as it were the backside of grace. Speaking of backsides, Omar Ghaleez now said:

‘Must I really stand in the corner for three minutes, repenting for watching porn? Isn’t the fifty quid satisfactory?’

‘You must.’

Bending his large, sheeny, rotund skull, Dr. Spine took the check for fifty pounds: sterling; satisfied himself of the young man’s repentance and his promise not to access such websites again; and, alone once more, resumed his note-taking: small and black and spidery…

He was by all the fates a deeply sensitive man. His long-borne berth there at that Oxford College had always been for him a pastoral commission as much as an academic one. He wished for the burgeoning youths under his direction to be gentlemen and ladies, as much as budding scholars. Since his mother had died, prematurely, by stark suicide, he’d clutched-at his pastoral role with more insistence than had previously been the case – before, that is, that heart-wrecking loss, a burrowing; a burrowing hole.

The small round ashtray to his side emitted wafts of slow, thick, curling smoke – a half-finished fag in-laid at one of its indented sides. Dr. Spine exhaled; and it was a loaded sigh…

***

Because she was a swan, colored by utter-snow; and because she was the calmed surface of the placid lake in question, as well – Maryam Ghaleez was not pleased to hear of her son’s misdemeanor. Pornography was one thing, if not too palatable; but to be caught and disgraced for it – well, there was no “pleasure” in that. But before she could second her smacking disapproval, her son said:

‘It was only fifty pounds; and there were others, many, too.’

In fact, that was the strange thing about it. He’d heard of friends, or coevals, having been caught (and fined) in flagrante as it were – but they had been using computers on campus; whereas he had surfed, so salaciously, from the comparative safety of the two-bedroom flat down by the canal near the train station which he shared with a close friend. In fact, that is, how did they (the college authorities) know? It was something worth looking-into; but for the moment: neither here nor there.

Presently, his mother was seated on a short tomato-red swivel chair, partly busy at her make-up. It was a slim-shouldered, oblong dressing-room, lined by cupboards of clothes on one side and a long white desk opposite, on which lay a wide and savvy array of sprays and creams and ointments. Since earliest memory, the room had been associated in Omar Ghaleez’s teeming imaginary, not only with the musk of motherhood, but also for the miracle of the double-sided mirror stood at the quested center of the long white counter. One round side was a normal mirror. The other: telescopically enlarged its reflection by a factor of, at least, ten – it had seemed to the smitten child. In any case, that was childhood – summery, halcyon. And yet, though he may well have grown to a good, grand nineteen years-of-age – he was being berated, presently, like a pubescent boy…

(No; there is no “pleasure” in that…)

(No; there is no “pleasure” in that…)

His mother evinced the honey-ochre of wheat and Mediterranean skin; had curious sea-emerald eyes; and sported large and syrupy golden bangles by ear and wrist. And yet, though she’d the air and colors, thus, of a distance-traipsing gypsy – she was scandalized; or at least, displaying the pretense of such.

‘You shouldn’t; you mustn’t….’

‘But everyone does.’

She pursed her lips, thick Semitic lips the color of redder salmon. Folding her mouth like this, inching it inwards at the burly rows of chunky-white teeth, was a tic with her – indicating enervation.

‘It’s not the fifty pounds…’

‘I know that.’

‘It’s the shamefulness…’

‘“Shame…”’ He said it with a distinct hint of caprice – because he continued:

‘Now that’s a noun, a “property”, if you will, with both an “internal” and an “external” negation.’

His mother’s brow began to widen; it was the look of devastating expectation.

‘Now: Mum,’ he continued, in mock-heroic vein:

‘You must realize that words like “yellow” only have “external negations” – “not yellow.” But “shame” is a property – shall we say? – like “good.” One has “not good” and one has “bad” – which are patently not the same. Similarly,’ and he half-clucked his tongue, a habit he shared with his recently-deceased uncle, Bassam, his mother’s younger brother,

‘Similarly – I’d have thought, anyway: we have “un-shameful” and we have “honorable.” I suppose.’

The (fighting) grimace on her face slowly broke into a gravelly chuckle and then a wide and clownish smile. Having a brilliant son was like having an eternal sunrise in the eternal possession of one’s eyes. After a small pause, letting the mirthful dust settle, his mother asked about the girl.

(You know: “the girl?”)

His former bantering prolixity vanished; he found himself: word-lost. Quick-stopped, thus, he mumbled something between dismissive and incoherent, deflecting the conversation to a different topic. She knew enough, his mother, to play along, feigning ignorance; pretending to be a whole lot denser, stupider than she was in fact. It was a type of graciousness mother and son shared – peas in a green (and greener) pod.

Chapter 2: Clara Enters The Fray

Because she wasn’t quite present at the beginning of the fight, she was treading uncertain ground. She’d avid inklings it might have been over (the phantom of) a woman, but she wasn’t sure. David, Nick, had no clue, returning a few minutes later from the back where they’d been collecting and registering the day’s second delivery of stock. Clara hesitated; but soon intervened with a forced, strong hand; though her near-citrus colored hands were small and skinny – those of a nimble puppeteer perhaps.

The scuffle between the two men – one, seemingly, from Africa, the other a local Oxonian – began the process of petering out. The African man had put up two steady bobbing fists, donning the periodic mores of a trained pugilist, but the pug-faced Briton had rubbished that pose by smacking the black chap right on the nose, breaking it. Now regaining his stature, the African man made pacifying motions, which Clara took as her cue to intervene and seal the quieting. She offered the slighted Briton a free drink on the house, and it was duly accepted. Though the two brief combatants – one svelte in dark acidic brown, the other pig-pink – hadn’t suddenly become the best of chums, the short spate of violence seemed to have calmed and relieved the both of them. As the local took his first sip of free beer, the second, darker man nodded towards him mutely and ambled out, wonky in his gait, feeling at his proboscis, searching for the cracked slippage of cartilage or bone.

Boehme’s – one of the swankiest café-bar-bistros off the Oxford High Street – was back to being its staple locus: a gamboling space for the more well-off students in that medieval university city; most of whom couldn’t tell their right fist from their left.

***

For many weeks now, the anomaly had haunted her. She’d had these lucid visions of the older woman, accompanied by a white noise, a kind of beaming in the susurrus. They weren’t hallucinations, or at least she assumed as much, because when they occurred, day or night, she hadn’t a thimbleful of booze or drugs in her veins. The woman who appeared to her, the ghostly presence, was leonine of make, with russet and honey hair. She’d these sparkling eyes, mixed of mint and almond. She never said anything, whenever she appeared: which was a relief. But the hauntings of this woman had Clara shook-up.

She hadn’t told anyone about them, hoping, rather desperately, that they’d cease. But if anything they were becoming more frequent, and the look in the woman-visitant’s eyes more piercing, more urgent. Seated now with her closest friend, Beth, she tried to broach the subject.

‘Beth?’

‘Yes?’

‘Do you believe in ghosts?’

Beth was of good, ardent Gaelic stock. In fact, coming up to Oxford had been the first time she’d lived anywhere but in the voluptuous, wet and luscious Galway of Ireland’s southern west coast. But since then, she’d made up for lost time; so she now said, tartly-smiling:

‘Well, yes, of course, darling. I’ve loads of them.’

Clara smiled, as though into a distance. The gesture seemed to quieten her friend’s buoyancy.

‘You mean, for real? For real: ghosts?’

Clara nodded, slowly, hesitantly.

‘I’ve never seen one, if that’s what you mean.’

Her friend masked her disappointment a little clumsily, so Beth continued:

‘Why? Have you? Have you seen one?’

Clara paused, stuck.

‘Because if you have: that’d be grand!’

She now withdrew the pencil she often used to keep the bird-like bundle of her hair in place and shook out her mane.

‘Maybe I have,’ she said. ‘Or maybe I haven’t.’

‘Well, darling, that sounds just like how a ghost would be! I think it’s smashing.’

As they sat there, sipping pink cocktails into the night, Beth tried to entice her friend to unload the details of her visions. But Clara was reticent, and because it was her nature to be reticent at times, Beth gracefully took the lead in the chinwag. She started telling her friend of stories she’d been told when just a girl, about reincarnated presences. One story in particular from the panoply struck Clara with more force than the rest, but she didn’t know why. Perhaps it was the brilliance of Beth’s telling it, perhaps it was the cumulous of the booze.

She’d an uncle, you see, who’d been a soldier in the IRA. He’d gone off to fight for the cause up north when only nineteen. And throughout her childhood summers, when said uncle would sometimes come to visit them, taking a wee holiday from freedom-fighting, he would leave distinct and uncanny stories winding in her head. Most of the time the violence or gore was expunged in the telling – her maternal uncle wasn’t callous. But one time he’d told the story of a young catholic boy he’d met (whose family he’d met) who had been taken for exorcism more than once, and with no palpable results.

As it turned out, round about the age of five or six he started to speak in visions and rants, peopling tales no six year old might have ever had the capacity to tell without actually having been present at and during the places of his yarns. And a repeated motif in his visions was how he was actually not the boy they thought he was; how he was another boy, who’d been killed in vengeance many years back, before the telling boy was born, in fact, and who’d been buried in some abandoned location this same boy knew to the very meter.

After exorcism hadn’t worked, and after the psychologists had given up, one day, his parents decided to follow his instructions about the buried, murdered boy. The frightening thing was that when they went there and – purely for the sake of hopefully curing their child of his illness and his delusions – had dug up at the spot he’d pointed out for them – they actually found a skeleton, which, later, they were informed, was identified as the very boy their own boy claimed to be. It was one of the most frightening stories Beth had ever heard; but the funny thing was, she only recalled it in all its gory visceral detail now, as Clara had mentioned her paranormal experiences. Maybe it was the sixth (or seventh) Martini as she finished the tale, maybe it was the reliving of a long-buried and traumatic memory, but Beth ended up in floods of tears, and Clara had to tend to her – where she was the one originally soliciting comfort!

Later that night, Clara had a dream.

To start off with, she and Beth were fighting, clawing at each other’s faces and leaving long, but strangely painless, red streaks across each other’s cheeks. The dream then shifted to Beirut, of all places! How she knew it was Beirut, never having been there, was, like a dream, mysterious to her but also implicitly taken for granted. She was in the passenger seat of a car driving up from ‘Beirut’ to the mountains above that warring city; because it was warring (strangely, her dream had Lebanon in the early eighties, during the notoriously violent civil war there); and as they winded up the curling mountain road in a cheap battered sky-blue Mercedes, she was weeping floods, but silently, the driver of the car taking no notice. There was a thudding coming from the boot of the car. Every so often, Clara would turn her head, looking back through the car’s back window, to the surface of the boot from where the thudding, the desperate thudding seemed to be coming from. She tried to exclaim to the swarthy driver, repeatedly screaming for him to stop, but neither voice emerged from her shrieking mouth, nor did the driver take any notice. No, the swarthy thirty-something man was adamantly honed onto the up-winding road in front of him. The thudding from the boot continued, and then a white noise like a beaming from some susurrus, and then she slowly emerged from her slumber, to the sound of earthly thudding, out there, in the real world.

It was nine-thirty in the morning, roughly, and someone was banging on the door downstairs. Seemingly, all her housemates were still asleep, or, had spent the previous night with some paramour. So Clara made her gentle way downstairs, to find the postman with a package, needed to be signed for. She signed, though still blurry-eyed, in quick versatile penmanship. It was actually addressed to her, or, she assumed as much; because the address was accurate; but it was only the fact that the name of the recipient was missing a ‘C’. The small square package was addressed to a ‘Lara’ followed by the first initial of Clara’s surname. It was enough to go on, so, while pouring out her morning’s green tea, she duly opened it.

Inside she found a long silken beige-colored pashmina, all smashed up in the envelope; plus a recent issue of some literary journal, with a dog-eared page opening onto a poem which, bizarrely, seemed to be dedicated to the same ‘Lara’ on the outside of the package. It was a beautiful poem. But Clara was at a loss. She racked her brain. But for the minute, no clue came to hand. And for all her recent visions, Clara was a pragmatic kind of girl; not quite a tomboy, but neither was she your staple and silly girly-girl, who might go stark raving mad over such a mystery. She quickly and logically detailed her mental options. She didn’t know who it was from, or why it was sent. It was, ostensibly, directed at and for her. It might be a secret admirer, it might not. In fact, it might have a rationale beyond all present comprehension, which was not only possible, but probable, likely. Clara was studying philosophy, as one of her subjects in her undergraduate degree. And she’d progressed enough in her (very conscientious) studies, to be able to countenance the idea that reason, our sense-making organ, might not always be in a position to fully round and grasp the data that surrounded and pinioned us. Her recent visions, say….

At noon, she’d a four hour shift at Boehme’s. So, finishing her breakfast, finishing a few early-morning perfunctory emails, she set off down the last leg of the Cowley Road, crossed the Magdalen Bridge, beneath which a few stray groups were punting in the shallow waters, and arrived, as was her wont, a good half-an-hour early at her workplace. She needed the part-time gig there to help finance her undergraduate degree. She was a Rhodes Scholar, in-wending from a country abroad which was still a part of the Commonwealth – but she needed to supplement that well-deserved subsidy; or at least, wished to.

Young still, but ambitious – by all the portents she seemed destined to succeed in a world whose worldliness was always going to be a struggle. Fortune (‘Fortuna’, for the Machiavelli on whom she’d recently attended a lecture) seemed to be eminently on her side. And Naseeb: was one Arabic word for that same I-taut property in a life….

Chapter 3: The Magna Carta

There was a gaggle and a gang of girls screaming and screeching loudly and lewdly down the road. Their harpy-like echolalia reeked and wrecked across Oxford’s navy-dark sky. They were so loud and so insistent that their noise travelled through the thick stone walls of that college library like a low-lit monkish cloister.

Omar Ghaleez stirred, jolted his head upwards, and drowsily peered at his watch. The almonds of his eyes were streaked with wonky crimson lines. It was two forty-three in the morning. About twenty books of different shapes and sizes – all in a wonderful array of different colors, some dog-eared, some laid neatly-stacked at the end of his desk, some on the floor, some strays half on the desk, half hanging on air off the side – mutely serenaded his brief slumbers.

For a split-second, now, emerging from lumpen sleep, he panicked; then checked. Thankfully, the last version of his now twelve-thousand-word essay had been saved. That said: the slippage of his hands while he’d fallen haplessly into dozing for the last half-hour had resulted in a long series of ‘zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz’s after the last sentence of his conclusion. So, testily, he deleted the errata, packed up his things, placed his laptop in its black sack and made his way back to his room, at the top right corner of the college.

He’d only recently moved there, from his private-rented flat down by the canal near the train-station. He’d decided he wanted to live like all his peers, eschewing privilege.

Just before falling onto his small cushioned bed, he heard again the screaming of a few stray girls, abandoned no doubt in the early hours by their beaux. It was like the cah-cah-cah of rabid, ravenous gulls, circling spied prey…

The next day, his peer (so-called) sat next to him had done all that was expected of him. His curly blond hair and his steely blue eyes and his pale white skin seemed to be self-satisfied; absurdly-smug. The tutor, a woman with a fierce brow, had rather damply praised his effort. And then Omar Ghaleez began to read from his essay, a veritable bushel of white paper like reaped wheat. The sight of it made his blond fellow-tutee cower and whimper almost, a scratched puppy, while the tutor’s pupils dilated – indicating, one would have thought: lust.

By the conclusion he came to a rallying nugget. He finished the virtuoso reading by saying that all the facile and hackneyed tropes about Marx being a hard determinist were simply non-sense. If Marx meant by (as just one infamous example) the ‘specter haunting Europe’ some kind of helpless inevitability to historical processes – then why bother to write the rallying document in the first place! Why make the effort of praxis, even that praxis that was theorizing, if it was all going to happen anyway? Indeed, to close, Omar Ghaleez remarked that Marx had only meant that there were certain macro, as it were, tendencies, indicated by the material state at any one time of any body politic; that that was why he’d never actually drafted any kind of blueprint for what socialism or indeed communism might look like when it did, as he so wished it to, surpass the necessary, but soon-to-be-discarded, stage of market capitalism. He never tried to draft-out the future in anything like concrete detail. His brief was merely to suggest where things were tending, and equally, thus, where he hoped they would, and should, in the end, tend…

Forty minutes later, the tutor was flabbergasted. Gave him an Alpha (unheard-of) to his face and wondered aloud whether Omar Ghaleez knew more about the subject than even she did. His native shyness gave way to pleasure; the tutor was almost flirting with him! She’d the aspect of a lioness, cossetting a favorite cub. Her beaming smile was ludicrous, while she toyed and fingered with the necklace at her open neck. He’d already noticed, through the crack of the door half-ajar on the right, the small brown teddy bear that was neatly perched upon the pillow of the bed in the ancillary bedroom of those digs.

‘I especially like the footnote you’ve inserted at the end, tacked onto that quite eloquent conclusion.’

He’d suggested in that concluding footnote that John Stuart Mill’s near-contemporary position on the question of determinism was compatible. Mill had had to accept, as an eminently scientific mind, the ineluctable burden of causality, and thus determinism. He’d merely suggested that the space of free will, of intention, was in choosing, by one’s timely intervention, which determinants were to be the ones at play. It was a quite nice compromise, he thought. And very, well: English…

For close to a minute a by turns ponderous and beaming silence reigned in the room. The tutor’s eye-contact was unnerving, beguiling.

Omar Ghaleez tried to play it down, hoping to allay the rather alarming lustfulness in that gaze. It occurred to him now, though, that she’d the skin, the hair color, and the broad lineaments of facial structure as his mother had. But her eyes: they seemed to be forever squinting, deep-set and narrow in her brow. More like a tiny bird’s than his mother’s – shaped like a wide gazelle’s, clown-big; as was her smile…

Dr. Julie Burgess waxed lyrical to all the Fellows about the young man’s essay: so prescient, copious, thorough and well, just plain, stark brilliant – for a second year student! Most doctoral candidates couldn’t put up such a fight, and in such short time.

Seated at the head of that dining table, Dr. Spine pursed his pink reed-thin lips, in a motion that seemed to wish to steady the head and the body as much as the soul; whether because of the drink he’d already guzzled, or not. A plump, butch colleague helped him out of his seat now and walked him away for the rest of the evening. This wasn’t unusual, so the rest of the Fellows merely nodded good nights, and carried on with their low-toned, tittering banter. Meanwhile, Dr. Julie Burgess spoke to none, seemingly drifting off in daydream by evening. She hadn’t had a drop to drink.

***

With his large right hand palming and rubbing the back of his skull, walking, no, traipsing – a touch-too-tipsy – backwards and forwards across the living room of the apartment, Dr. Spine was trying to square a circle. And the plump, butch woman who sat opposite him, beseeching him to be seated and to share the dilemma that had him in its motive grip, to share the burden to lighten it – well, she was flummoxed. In some strange way, she knew she could and would be of little avail. She knew the man she was trying to calm, and she knew the man she was failing to calm. She knew him as a skeleton knows the fleshed body that coats it, with all its sad fanfare of sinew, of tissue and blood. Dr. Spine stopped in his pacing now, turned and looked to his childhood friend.

‘You don’t seem to understand, Laura. The damned young chap is spoilt, spoilt-rotten. Could he be a genius?’

‘And why shouldn’t he be? A kind of prodigy, I mean.’ Laura’s curt crop of corn-colored hair made her look plumper than she already was.

‘It’d be a damned fine coincidence if he was!’

‘How so? Come on: explain yourself.’

‘It’s hard to say…’

‘Listen, I couldn’t care less about the boy; it’s you I’m worried about. And you seem to be worried about him. Hence….’

‘A syllogism, I suppose.’

‘Well, yes.’

‘Look, Laura. You’ve seen him. Does he look like a genius to you?’

‘Why?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I mean: why do you ask? And I also mean: Why? What should a genius look like?’

‘Certainly not like a man who belongs in one of those glamorous bloody glossy magazines! And yet…’ there was the very tiny hint of a pleased smile suggesting itself slowly across his face, widening his brow. Yes, he was indeed touched, a tad too-tipsy.

‘Yes?’

‘Well, perhaps one might well have a crib for it after all.’

‘A way of understanding the phenomenon: a phenomenon, then?’ Laura handled her drink with more aplomb.

‘It may be reasonable, perhaps – if not rational. There’s always something so handsomely English about the contingent happening, the idiosyncrasy, the fluke.’ It was hard to tell, in this sodden state, exactly what degree of seriousness to attribute him.

‘The red herring probably was an Englishman…’ she tallied-in, hoping to keep up.

But Dr. Spine continued in his slurring train of thought, piqued and delighted at the same time.

‘We may’ve a “Rosetta Stone,” of sorts; I may be on the verge of putting my mind to rest…’ And for the first time in half an hour he lifted his right palm from its agonistic position, rubbing at the back of his skull, waved it in the air, and landed it at his right hip. He paused in his stride, swayed; but now seemed more certain, controlled – though what he was about to conclude was hilarious.

‘Yes….’

‘Yes. One might, one just might parse the phenomenon by saying he was, or is, rather, indeed a kind of Englishman – the fluid essence of one, as it were.’

‘He’s Lebanese, isn’t he?’ She was doing her best to be a caring ear, or a partner in broken comedy.

‘Bother that! What does “The Lebanon” have to do with it? He’s English. He’s like a rule of thumb, more like a rule of thumb, than a simple, facile, razing rule. He’s the law as it will turn out to be, as it may be, as it may work out to be.’

‘He’s the Magna Carta, then?’ Laura betrayed her butch and plumpish frame by giggling like a teased schoolgirl. Her pink skin was pinker against the staid white shirt she wore above a pair of light blue jeans. She kicked off her shoes now, and Dr. Spine and his childhood friend – who happened to be the college counsellor – widened into bellows.

‘Yes, quite. The young chap just is the Magna Carta.’

He looked resolute, emboldened, but mischievous at the same time. So when Laura now asked, as she couldn’t help but ask:

‘And the pornography-watching?’

Dr. Spine furrowed his brow.

‘Yes. But then: that just makes it the more telling.’ And he drew a quick circle in the air with his right index finger as if to show, figuratively, geometrically, how it all did indeed work out.

Laura knew of course that he was sometimes employed as a sort of mild-mannered consultant for British Intelligence – so descrying where the real motives of his mind truly came out, was always an elusive gambit; though they’d been friends from childhood, Dr. Mark Spine never let-on about that side of his working affairs. She’d just assumed he’d been informed by knowing parties that the young Lebanese boy in his second year at college, was, well, of genius-level intelligence. Why the news had quite evidently troubled him so, though, she hadn’t quite fathomed. And she wondered if she ever would – even in the fullness of time. But for now, settling on the silly metonym of the “Magna Carta” served to please him, drunk as he was – and to shut him up. She poured him another glass of sherry. Dr. Spine sat down, splay-like on the sofa. She brought him a duvet and a pillow – then walked out of the room. It was past one o-clock in the morning.

‘There are many ways to skin a cat: sir.’

‘Are there really?’

‘Yes; there are.’

It was a tad embarrassing – this situation: hanged, drawn, quartered. The long dangly older man – sporting a large bald head like a waxen, yellow-pink bowling ball, and dressed in clean-pressed black trousers and pristine white shirt, opened widely at the collar – was also feeling slightly embarrassed. It just wouldn’t do – this pornography business. For all the young man opposite being one of his favorites – house rules were house rules; one shouldn’t, one mustn’t let the team down; a gentleman owed it, as it were, to his club.

They were seated over ten feet apart; the distance was both studied, and studious. The wide oval-shaped room, a grand Don’s study, was lit this afternoon by only the one large window at the farther side; though fitted with lamps, by choice they were only rarely put to use. This dark and smoldering bear-like-cave, this book-lined lair evoked auras of burgundy and of sepia and of oak – wine-colored comfort from a different, less-rushed eon. The Don in question sat at the farther end, just beside the sole window of that monkish keep, in a low and fatly-cushioned armchair, wine-toned, too; his long and spindly legs were crossed over each other, rather effeminately, as he toked occasionally on a white-tipped cigarette. The student facing him, seated on a lime-grey couch, was hunched forward over himself and over the small square table that lay just in front – ashtrays out-laid there, too. But the younger party at this parley didn’t smoke; or had chosen not to: in this scenario.

‘The fine will be fifty pounds: sterling,’ the older man now said.

‘That’s fine.’ Omar Ghaleez grinned from ear to ear, inanely delighted at the sight of his near-bumbling, now-scandalized interlocutor.

‘Stop that!’ He exhaled a long lungful of smoke, a small hint of in-sufferance and disdain about his reed-thin lips.

‘What?’

‘That smirking,’ he said. ‘It’s: smug.’

Omar Ghaleez stopped his rictus; and not because it was requested. No; it was the adjective, “smug” that had done it. “Smug” was the operative culprit. It was, in truth, an effortlessly beautiful word. But a word, also, and at the same time, he hated. And the love and the hatred formed a taut and poignant antagonism in his mind, presently. He’d often been dubbed: “smug.”

It was a kind of “grace,” he now supposed to himself – smugness, that is. Yes: something a philosopher had written by the wayside spurred and suggested the analogy to him. Said philosopher had written of grace, tangentially, as a, or the, great equalizer of or in human behavior. To be “grace-ful” was to be susceptible to posthumous (poetic?) justice; was to forge good, straight timber – after the fact – from splinters and orphaned shards. Hypocrisy, say, or syncretism in self and/or world, when smoothed-out, styled (if retroactively) was a way of understanding what grace just was. Whether we meant a clumsy individual’s faux pas followed by its imminent redemption in a face-saving jest, or, the action, say, of the Holy Spirit retroactively justifying and in-jigging contradictory dogmas as the visible body of the Church changed tacks in its scuttling development – either way: grace was the processed outcome, the working upshot. Smugness, by turns, was as it were the backside of grace. Speaking of backsides, Omar Ghaleez now said:

‘Must I really stand in the corner for three minutes, repenting for watching porn? Isn’t the fifty quid satisfactory?’

‘You must.’

Bending his large, sheeny, rotund skull, Dr. Spine took the check for fifty pounds: sterling; satisfied himself of the young man’s repentance and his promise not to access such websites again; and, alone once more, resumed his note-taking: small and black and spidery…

He was by all the fates a deeply sensitive man. His long-borne berth there at that Oxford College had always been for him a pastoral commission as much as an academic one. He wished for the burgeoning youths under his direction to be gentlemen and ladies, as much as budding scholars. Since his mother had died, prematurely, by stark suicide, he’d clutched-at his pastoral role with more insistence than had previously been the case – before, that is, that heart-wrecking loss, a burrowing; a burrowing hole.

The small round ashtray to his side emitted wafts of slow, thick, curling smoke – a half-finished fag in-laid at one of its indented sides. Dr. Spine exhaled; and it was a loaded sigh…

***

Because she was a swan, colored by utter-snow; and because she was the calmed surface of the placid lake in question, as well – Maryam Ghaleez was not pleased to hear of her son’s misdemeanor. Pornography was one thing, if not too palatable; but to be caught and disgraced for it – well, there was no “pleasure” in that. But before she could second her smacking disapproval, her son said:

‘It was only fifty pounds; and there were others, many, too.’

In fact, that was the strange thing about it. He’d heard of friends, or coevals, having been caught (and fined) in flagrante as it were – but they had been using computers on campus; whereas he had surfed, so salaciously, from the comparative safety of the two-bedroom flat down by the canal near the train station which he shared with a close friend. In fact, that is, how did they (the college authorities) know? It was something worth looking-into; but for the moment: neither here nor there.

Presently, his mother was seated on a short tomato-red swivel chair, partly busy at her make-up. It was a slim-shouldered, oblong dressing-room, lined by cupboards of clothes on one side and a long white desk opposite, on which lay a wide and savvy array of sprays and creams and ointments. Since earliest memory, the room had been associated in Omar Ghaleez’s teeming imaginary, not only with the musk of motherhood, but also for the miracle of the double-sided mirror stood at the quested center of the long white counter. One round side was a normal mirror. The other: telescopically enlarged its reflection by a factor of, at least, ten – it had seemed to the smitten child. In any case, that was childhood – summery, halcyon. And yet, though he may well have grown to a good, grand nineteen years-of-age – he was being berated, presently, like a pubescent boy…

(No; there is no “pleasure” in that…)

(No; there is no “pleasure” in that…)

His mother evinced the honey-ochre of wheat and Mediterranean skin; had curious sea-emerald eyes; and sported large and syrupy golden bangles by ear and wrist. And yet, though she’d the air and colors, thus, of a distance-traipsing gypsy – she was scandalized; or at least, displaying the pretense of such.

‘You shouldn’t; you mustn’t….’

‘But everyone does.’

She pursed her lips, thick Semitic lips the color of redder salmon. Folding her mouth like this, inching it inwards at the burly rows of chunky-white teeth, was a tic with her – indicating enervation.

‘It’s not the fifty pounds…’

‘I know that.’

‘It’s the shamefulness…’

‘“Shame…”’ He said it with a distinct hint of caprice – because he continued:

‘Now that’s a noun, a “property”, if you will, with both an “internal” and an “external” negation.’

His mother’s brow began to widen; it was the look of devastating expectation.

‘Now: Mum,’ he continued, in mock-heroic vein:

‘You must realize that words like “yellow” only have “external negations” – “not yellow.” But “shame” is a property – shall we say? – like “good.” One has “not good” and one has “bad” – which are patently not the same. Similarly,’ and he half-clucked his tongue, a habit he shared with his recently-deceased uncle, Bassam, his mother’s younger brother,

‘Similarly – I’d have thought, anyway: we have “un-shameful” and we have “honorable.” I suppose.’

The (fighting) grimace on her face slowly broke into a gravelly chuckle and then a wide and clownish smile. Having a brilliant son was like having an eternal sunrise in the eternal possession of one’s eyes. After a small pause, letting the mirthful dust settle, his mother asked about the girl.

(You know: “the girl?”)

His former bantering prolixity vanished; he found himself: word-lost. Quick-stopped, thus, he mumbled something between dismissive and incoherent, deflecting the conversation to a different topic. She knew enough, his mother, to play along, feigning ignorance; pretending to be a whole lot denser, stupider than she was in fact. It was a type of graciousness mother and son shared – peas in a green (and greener) pod.

Chapter 2: Clara Enters The Fray

Because she wasn’t quite present at the beginning of the fight, she was treading uncertain ground. She’d avid inklings it might have been over (the phantom of) a woman, but she wasn’t sure. David, Nick, had no clue, returning a few minutes later from the back where they’d been collecting and registering the day’s second delivery of stock. Clara hesitated; but soon intervened with a forced, strong hand; though her near-citrus colored hands were small and skinny – those of a nimble puppeteer perhaps.

The scuffle between the two men – one, seemingly, from Africa, the other a local Oxonian – began the process of petering out. The African man had put up two steady bobbing fists, donning the periodic mores of a trained pugilist, but the pug-faced Briton had rubbished that pose by smacking the black chap right on the nose, breaking it. Now regaining his stature, the African man made pacifying motions, which Clara took as her cue to intervene and seal the quieting. She offered the slighted Briton a free drink on the house, and it was duly accepted. Though the two brief combatants – one svelte in dark acidic brown, the other pig-pink – hadn’t suddenly become the best of chums, the short spate of violence seemed to have calmed and relieved the both of them. As the local took his first sip of free beer, the second, darker man nodded towards him mutely and ambled out, wonky in his gait, feeling at his proboscis, searching for the cracked slippage of cartilage or bone.

Boehme’s – one of the swankiest café-bar-bistros off the Oxford High Street – was back to being its staple locus: a gamboling space for the more well-off students in that medieval university city; most of whom couldn’t tell their right fist from their left.

***

For many weeks now, the anomaly had haunted her. She’d had these lucid visions of the older woman, accompanied by a white noise, a kind of beaming in the susurrus. They weren’t hallucinations, or at least she assumed as much, because when they occurred, day or night, she hadn’t a thimbleful of booze or drugs in her veins. The woman who appeared to her, the ghostly presence, was leonine of make, with russet and honey hair. She’d these sparkling eyes, mixed of mint and almond. She never said anything, whenever she appeared: which was a relief. But the hauntings of this woman had Clara shook-up.

She hadn’t told anyone about them, hoping, rather desperately, that they’d cease. But if anything they were becoming more frequent, and the look in the woman-visitant’s eyes more piercing, more urgent. Seated now with her closest friend, Beth, she tried to broach the subject.

‘Beth?’

‘Yes?’

‘Do you believe in ghosts?’

Beth was of good, ardent Gaelic stock. In fact, coming up to Oxford had been the first time she’d lived anywhere but in the voluptuous, wet and luscious Galway of Ireland’s southern west coast. But since then, she’d made up for lost time; so she now said, tartly-smiling:

‘Well, yes, of course, darling. I’ve loads of them.’

Clara smiled, as though into a distance. The gesture seemed to quieten her friend’s buoyancy.

‘You mean, for real? For real: ghosts?’

Clara nodded, slowly, hesitantly.

‘I’ve never seen one, if that’s what you mean.’

Her friend masked her disappointment a little clumsily, so Beth continued:

‘Why? Have you? Have you seen one?’

Clara paused, stuck.

‘Because if you have: that’d be grand!’

She now withdrew the pencil she often used to keep the bird-like bundle of her hair in place and shook out her mane.

‘Maybe I have,’ she said. ‘Or maybe I haven’t.’

‘Well, darling, that sounds just like how a ghost would be! I think it’s smashing.’

As they sat there, sipping pink cocktails into the night, Beth tried to entice her friend to unload the details of her visions. But Clara was reticent, and because it was her nature to be reticent at times, Beth gracefully took the lead in the chinwag. She started telling her friend of stories she’d been told when just a girl, about reincarnated presences. One story in particular from the panoply struck Clara with more force than the rest, but she didn’t know why. Perhaps it was the brilliance of Beth’s telling it, perhaps it was the cumulous of the booze.

She’d an uncle, you see, who’d been a soldier in the IRA. He’d gone off to fight for the cause up north when only nineteen. And throughout her childhood summers, when said uncle would sometimes come to visit them, taking a wee holiday from freedom-fighting, he would leave distinct and uncanny stories winding in her head. Most of the time the violence or gore was expunged in the telling – her maternal uncle wasn’t callous. But one time he’d told the story of a young catholic boy he’d met (whose family he’d met) who had been taken for exorcism more than once, and with no palpable results.

As it turned out, round about the age of five or six he started to speak in visions and rants, peopling tales no six year old might have ever had the capacity to tell without actually having been present at and during the places of his yarns. And a repeated motif in his visions was how he was actually not the boy they thought he was; how he was another boy, who’d been killed in vengeance many years back, before the telling boy was born, in fact, and who’d been buried in some abandoned location this same boy knew to the very meter.

After exorcism hadn’t worked, and after the psychologists had given up, one day, his parents decided to follow his instructions about the buried, murdered boy. The frightening thing was that when they went there and – purely for the sake of hopefully curing their child of his illness and his delusions – had dug up at the spot he’d pointed out for them – they actually found a skeleton, which, later, they were informed, was identified as the very boy their own boy claimed to be. It was one of the most frightening stories Beth had ever heard; but the funny thing was, she only recalled it in all its gory visceral detail now, as Clara had mentioned her paranormal experiences. Maybe it was the sixth (or seventh) Martini as she finished the tale, maybe it was the reliving of a long-buried and traumatic memory, but Beth ended up in floods of tears, and Clara had to tend to her – where she was the one originally soliciting comfort!

Later that night, Clara had a dream.

To start off with, she and Beth were fighting, clawing at each other’s faces and leaving long, but strangely painless, red streaks across each other’s cheeks. The dream then shifted to Beirut, of all places! How she knew it was Beirut, never having been there, was, like a dream, mysterious to her but also implicitly taken for granted. She was in the passenger seat of a car driving up from ‘Beirut’ to the mountains above that warring city; because it was warring (strangely, her dream had Lebanon in the early eighties, during the notoriously violent civil war there); and as they winded up the curling mountain road in a cheap battered sky-blue Mercedes, she was weeping floods, but silently, the driver of the car taking no notice. There was a thudding coming from the boot of the car. Every so often, Clara would turn her head, looking back through the car’s back window, to the surface of the boot from where the thudding, the desperate thudding seemed to be coming from. She tried to exclaim to the swarthy driver, repeatedly screaming for him to stop, but neither voice emerged from her shrieking mouth, nor did the driver take any notice. No, the swarthy thirty-something man was adamantly honed onto the up-winding road in front of him. The thudding from the boot continued, and then a white noise like a beaming from some susurrus, and then she slowly emerged from her slumber, to the sound of earthly thudding, out there, in the real world.

It was nine-thirty in the morning, roughly, and someone was banging on the door downstairs. Seemingly, all her housemates were still asleep, or, had spent the previous night with some paramour. So Clara made her gentle way downstairs, to find the postman with a package, needed to be signed for. She signed, though still blurry-eyed, in quick versatile penmanship. It was actually addressed to her, or, she assumed as much; because the address was accurate; but it was only the fact that the name of the recipient was missing a ‘C’. The small square package was addressed to a ‘Lara’ followed by the first initial of Clara’s surname. It was enough to go on, so, while pouring out her morning’s green tea, she duly opened it.

Inside she found a long silken beige-colored pashmina, all smashed up in the envelope; plus a recent issue of some literary journal, with a dog-eared page opening onto a poem which, bizarrely, seemed to be dedicated to the same ‘Lara’ on the outside of the package. It was a beautiful poem. But Clara was at a loss. She racked her brain. But for the minute, no clue came to hand. And for all her recent visions, Clara was a pragmatic kind of girl; not quite a tomboy, but neither was she your staple and silly girly-girl, who might go stark raving mad over such a mystery. She quickly and logically detailed her mental options. She didn’t know who it was from, or why it was sent. It was, ostensibly, directed at and for her. It might be a secret admirer, it might not. In fact, it might have a rationale beyond all present comprehension, which was not only possible, but probable, likely. Clara was studying philosophy, as one of her subjects in her undergraduate degree. And she’d progressed enough in her (very conscientious) studies, to be able to countenance the idea that reason, our sense-making organ, might not always be in a position to fully round and grasp the data that surrounded and pinioned us. Her recent visions, say….

At noon, she’d a four hour shift at Boehme’s. So, finishing her breakfast, finishing a few early-morning perfunctory emails, she set off down the last leg of the Cowley Road, crossed the Magdalen Bridge, beneath which a few stray groups were punting in the shallow waters, and arrived, as was her wont, a good half-an-hour early at her workplace. She needed the part-time gig there to help finance her undergraduate degree. She was a Rhodes Scholar, in-wending from a country abroad which was still a part of the Commonwealth – but she needed to supplement that well-deserved subsidy; or at least, wished to.

Young still, but ambitious – by all the portents she seemed destined to succeed in a world whose worldliness was always going to be a struggle. Fortune (‘Fortuna’, for the Machiavelli on whom she’d recently attended a lecture) seemed to be eminently on her side. And Naseeb: was one Arabic word for that same I-taut property in a life….

Chapter 3: The Magna Carta

There was a gaggle and a gang of girls screaming and screeching loudly and lewdly down the road. Their harpy-like echolalia reeked and wrecked across Oxford’s navy-dark sky. They were so loud and so insistent that their noise travelled through the thick stone walls of that college library like a low-lit monkish cloister.

Omar Ghaleez stirred, jolted his head upwards, and drowsily peered at his watch. The almonds of his eyes were streaked with wonky crimson lines. It was two forty-three in the morning. About twenty books of different shapes and sizes – all in a wonderful array of different colors, some dog-eared, some laid neatly-stacked at the end of his desk, some on the floor, some strays half on the desk, half hanging on air off the side – mutely serenaded his brief slumbers.

For a split-second, now, emerging from lumpen sleep, he panicked; then checked. Thankfully, the last version of his now twelve-thousand-word essay had been saved. That said: the slippage of his hands while he’d fallen haplessly into dozing for the last half-hour had resulted in a long series of ‘zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz’s after the last sentence of his conclusion. So, testily, he deleted the errata, packed up his things, placed his laptop in its black sack and made his way back to his room, at the top right corner of the college.

He’d only recently moved there, from his private-rented flat down by the canal near the train-station. He’d decided he wanted to live like all his peers, eschewing privilege.

Just before falling onto his small cushioned bed, he heard again the screaming of a few stray girls, abandoned no doubt in the early hours by their beaux. It was like the cah-cah-cah of rabid, ravenous gulls, circling spied prey…

The next day, his peer (so-called) sat next to him had done all that was expected of him. His curly blond hair and his steely blue eyes and his pale white skin seemed to be self-satisfied; absurdly-smug. The tutor, a woman with a fierce brow, had rather damply praised his effort. And then Omar Ghaleez began to read from his essay, a veritable bushel of white paper like reaped wheat. The sight of it made his blond fellow-tutee cower and whimper almost, a scratched puppy, while the tutor’s pupils dilated – indicating, one would have thought: lust.

By the conclusion he came to a rallying nugget. He finished the virtuoso reading by saying that all the facile and hackneyed tropes about Marx being a hard determinist were simply non-sense. If Marx meant by (as just one infamous example) the ‘specter haunting Europe’ some kind of helpless inevitability to historical processes – then why bother to write the rallying document in the first place! Why make the effort of praxis, even that praxis that was theorizing, if it was all going to happen anyway? Indeed, to close, Omar Ghaleez remarked that Marx had only meant that there were certain macro, as it were, tendencies, indicated by the material state at any one time of any body politic; that that was why he’d never actually drafted any kind of blueprint for what socialism or indeed communism might look like when it did, as he so wished it to, surpass the necessary, but soon-to-be-discarded, stage of market capitalism. He never tried to draft-out the future in anything like concrete detail. His brief was merely to suggest where things were tending, and equally, thus, where he hoped they would, and should, in the end, tend…

Forty minutes later, the tutor was flabbergasted. Gave him an Alpha (unheard-of) to his face and wondered aloud whether Omar Ghaleez knew more about the subject than even she did. His native shyness gave way to pleasure; the tutor was almost flirting with him! She’d the aspect of a lioness, cossetting a favorite cub. Her beaming smile was ludicrous, while she toyed and fingered with the necklace at her open neck. He’d already noticed, through the crack of the door half-ajar on the right, the small brown teddy bear that was neatly perched upon the pillow of the bed in the ancillary bedroom of those digs.

‘I especially like the footnote you’ve inserted at the end, tacked onto that quite eloquent conclusion.’

He’d suggested in that concluding footnote that John Stuart Mill’s near-contemporary position on the question of determinism was compatible. Mill had had to accept, as an eminently scientific mind, the ineluctable burden of causality, and thus determinism. He’d merely suggested that the space of free will, of intention, was in choosing, by one’s timely intervention, which determinants were to be the ones at play. It was a quite nice compromise, he thought. And very, well: English…

For close to a minute a by turns ponderous and beaming silence reigned in the room. The tutor’s eye-contact was unnerving, beguiling.

Omar Ghaleez tried to play it down, hoping to allay the rather alarming lustfulness in that gaze. It occurred to him now, though, that she’d the skin, the hair color, and the broad lineaments of facial structure as his mother had. But her eyes: they seemed to be forever squinting, deep-set and narrow in her brow. More like a tiny bird’s than his mother’s – shaped like a wide gazelle’s, clown-big; as was her smile…

Dr. Julie Burgess waxed lyrical to all the Fellows about the young man’s essay: so prescient, copious, thorough and well, just plain, stark brilliant – for a second year student! Most doctoral candidates couldn’t put up such a fight, and in such short time.

Seated at the head of that dining table, Dr. Spine pursed his pink reed-thin lips, in a motion that seemed to wish to steady the head and the body as much as the soul; whether because of the drink he’d already guzzled, or not. A plump, butch colleague helped him out of his seat now and walked him away for the rest of the evening. This wasn’t unusual, so the rest of the Fellows merely nodded good nights, and carried on with their low-toned, tittering banter. Meanwhile, Dr. Julie Burgess spoke to none, seemingly drifting off in daydream by evening. She hadn’t had a drop to drink.

***

With his large right hand palming and rubbing the back of his skull, walking, no, traipsing – a touch-too-tipsy – backwards and forwards across the living room of the apartment, Dr. Spine was trying to square a circle. And the plump, butch woman who sat opposite him, beseeching him to be seated and to share the dilemma that had him in its motive grip, to share the burden to lighten it – well, she was flummoxed. In some strange way, she knew she could and would be of little avail. She knew the man she was trying to calm, and she knew the man she was failing to calm. She knew him as a skeleton knows the fleshed body that coats it, with all its sad fanfare of sinew, of tissue and blood. Dr. Spine stopped in his pacing now, turned and looked to his childhood friend.

‘You don’t seem to understand, Laura. The damned young chap is spoilt, spoilt-rotten. Could he be a genius?’

‘And why shouldn’t he be? A kind of prodigy, I mean.’ Laura’s curt crop of corn-colored hair made her look plumper than she already was.

‘It’d be a damned fine coincidence if he was!’

‘How so? Come on: explain yourself.’

‘It’s hard to say…’

‘Listen, I couldn’t care less about the boy; it’s you I’m worried about. And you seem to be worried about him. Hence….’

‘A syllogism, I suppose.’

‘Well, yes.’

‘Look, Laura. You’ve seen him. Does he look like a genius to you?’

‘Why?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘I mean: why do you ask? And I also mean: Why? What should a genius look like?’

‘Certainly not like a man who belongs in one of those glamorous bloody glossy magazines! And yet…’ there was the very tiny hint of a pleased smile suggesting itself slowly across his face, widening his brow. Yes, he was indeed touched, a tad too-tipsy.

‘Yes?’

‘Well, perhaps one might well have a crib for it after all.’

‘A way of understanding the phenomenon: a phenomenon, then?’ Laura handled her drink with more aplomb.

‘It may be reasonable, perhaps – if not rational. There’s always something so handsomely English about the contingent happening, the idiosyncrasy, the fluke.’ It was hard to tell, in this sodden state, exactly what degree of seriousness to attribute him.

‘The red herring probably was an Englishman…’ she tallied-in, hoping to keep up.

But Dr. Spine continued in his slurring train of thought, piqued and delighted at the same time.

‘We may’ve a “Rosetta Stone,” of sorts; I may be on the verge of putting my mind to rest…’ And for the first time in half an hour he lifted his right palm from its agonistic position, rubbing at the back of his skull, waved it in the air, and landed it at his right hip. He paused in his stride, swayed; but now seemed more certain, controlled – though what he was about to conclude was hilarious.

‘Yes….’

‘Yes. One might, one just might parse the phenomenon by saying he was, or is, rather, indeed a kind of Englishman – the fluid essence of one, as it were.’

‘He’s Lebanese, isn’t he?’ She was doing her best to be a caring ear, or a partner in broken comedy.

‘Bother that! What does “The Lebanon” have to do with it? He’s English. He’s like a rule of thumb, more like a rule of thumb, than a simple, facile, razing rule. He’s the law as it will turn out to be, as it may be, as it may work out to be.’

‘He’s the Magna Carta, then?’ Laura betrayed her butch and plumpish frame by giggling like a teased schoolgirl. Her pink skin was pinker against the staid white shirt she wore above a pair of light blue jeans. She kicked off her shoes now, and Dr. Spine and his childhood friend – who happened to be the college counsellor – widened into bellows.

‘Yes, quite. The young chap just is the Magna Carta.’

He looked resolute, emboldened, but mischievous at the same time. So when Laura now asked, as she couldn’t help but ask:

‘And the pornography-watching?’

Dr. Spine furrowed his brow.

‘Yes. But then: that just makes it the more telling.’ And he drew a quick circle in the air with his right index finger as if to show, figuratively, geometrically, how it all did indeed work out.

Laura knew of course that he was sometimes employed as a sort of mild-mannered consultant for British Intelligence – so descrying where the real motives of his mind truly came out, was always an elusive gambit; though they’d been friends from childhood, Dr. Mark Spine never let-on about that side of his working affairs. She’d just assumed he’d been informed by knowing parties that the young Lebanese boy in his second year at college, was, well, of genius-level intelligence. Why the news had quite evidently troubled him so, though, she hadn’t quite fathomed. And she wondered if she ever would – even in the fullness of time. But for now, settling on the silly metonym of the “Magna Carta” served to please him, drunk as he was – and to shut him up. She poured him another glass of sherry. Dr. Spine sat down, splay-like on the sofa. She brought him a duvet and a pillow – then walked out of the room. It was past one o-clock in the morning.

Omar Sabbagh is a widely published poet, writer and critic. His first collection and his latest, fourth collection, are, respectively: My Only Ever Oedipal Complaint and To The Middle of Love (Cinnamon Press, 2010/17). His Beirut novella, Via Negativa: A Parable of Exile, was published with Liquorice Fish Books in March 2016; and a new, riveting collection of short fictions, Dye and Other Stories, was released in September 2017. He has published or will have published scholarly essays on George Eliot, Ford Madox Ford, G.K. Chesterton, Robert Browning, Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, Joseph Conrad, Lytton Strachey, T.S. Eliot, Basil Bunting, Hilaire Belloc, and others; as well as on many contemporary poets. He’s a BA in PPE from Oxford; three Ma’s, all from the University of London, in English Literature, Creative Writing and Philosophy; and a PhD in English Literature from KCL He was Visiting Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at the American University of Beirut (AUB), from 2011-2013. He now teaches at the American University in Dubai (AUD).