NOTICE

The Author begs Leave to preface the present Work with a most sincere and humble Apology – to all Doctors and Alienists who find themselves perusing these poor Pages, it is neither the Author’s Inclination nor his Aim to malign; nor does this Author desire to tarnish the golden Names of those esteemed Gentlemen, both in this Old World and in the New, on whose great Works he has so deeply relied, and which he is given on occasion to quote without Citation; for this Author acknowledges freely his Guilt of a most grave Crime: when he writes, he writes exactly What he Pleases.

***

From the journals of Theophilus Moore, M.D., M.R.C.P.

Friday, 22nd of March, 1895. Well – rather a long pause between the last entry and this. My work, it seems, has been preying on my mind. But! not to worry – I shall not let it consume me overmuch; I shall instead occupy these last few hours of the night in the bringing of this little record au courant.

Yesterday was a dull, wet, blustery sort of a day – the very worst of March. The rain, it is true, abated somewhat in the afternoon; yet it did not seem so, for the damp of the morning loomed heavily in the air. I believe that fog must have settled into my mind; for I had the impression, as I sat by my window on Harley Street, that the Thames, swollen brimful with rain, and unable to hold one drop further of water, had spilled its yellow-brown contents back up into the sky; thus creating those wreaths of yellow fog that all the men and horses passing by on Harley Street appeared to wade through. So heavy was this rain-light, that it cast a yellow shadow over the skin of the hand with which I wrote, and over my pale lined paper. I recollect an intense stillness: the sound of my pen scratching (I had not yet mended the nib), and the low drone of my client’s voice, against the patter of the rain and the wind outside – all else was muffled. But the room was neat – the board floor neatly scrubbed; the walls well-papered; my map of the brain and my old phrenologist’s skull dusted by Mrs Bechdel that morning (she comes Tuesdays and Thursdays, now). I glanced back down to my client’s case-file, and dipped my pen once more; the case-file, which I reproduce here, read as follows: –

John Paige, m., 32. Single. Present occupation: Clerk at Enos Batley & Co., Publishers – four days per week, only. Of the usual size and build; dark hair, dark eyes. Of usual means. No history of hereditary insanity; but neuro-degenerate taint (?) on the side of the mother (widowed 1879, remarried June 1880). Weak of body, and much addicted to self-abuse. Suffers from a pathological obsession with English grammar and orthography, viz., usage of semicolons vs. commas, periods, colons –

“Doctor?” enquired my client. I glanced up from the file. Mr Paige was gazing at me, with a countenance expressive of great earnestness. “Dr Moore, Sir,” my client repeated, “would you say that you agree?”

“Yes, quite,” said I. “Yes, Mr Paige, I believe you are correct.” I had not heard what Paige had said – it was that accursed rain, of course, blotting out every sound. “Do continue, Mr Paige,” I said.

Paige sighed, deeply. “You see, Doctor,” said he, “it is my work that is the trouble. Being in my line of business, of course, grappling with these words at all hours of the day – one cannot very well avoid it.”

“No,” said I. “No, naturally.”

“But it does not feel like a thought, Doctor.” (Paige was rather fond of italics). “It feels – how can I describe it?” Paige paused. “I feel it physically,” he said at last, decidedly. “It is a physical sensation. When I read a sentence with a semicolon misplaced, I feel a queer consciousness of every hair standing up on the top of my head – just the top – and I hate it! it tickles so.”

I opened a desk-drawer and took out a Trichonopoly. “Have you a hat to wear, Mr Paige?” asked I, as I reached for my matchbox.

“Not indoors, Doctor,” said Paige.

“A good tight hat is the best way to go.” Paige said something in reply; I did not hear. I wrote discreetly in his case-file: Somatic delusion relating to top of head. I took a long puff of my cigar.

There was something of a flush about Paige’s cheeks, as he spoke. His gesticulations – mild, at first – grew more violent as he progressed in his speech; and the pink spots on either cheek deepened correspondingly. It was a symptom, I reflected, as I watched the dun cigar-smoke cloud the air. To the man of science – and I trusted I might count myself as such – it was a clear symptom of that crude overexcitement which leads so many sane men down the black path of madness; the kind of case one might publish, perhaps, if one could only sort out one’s notes. The brown smoke before me was beginning to settle somewhat. Yet honesty must be sought, of course; honesty, above all. And I feared that Paige actually deepened this flush artificially, through pinching, perhaps, or some other such means; in imitation of that portrait of Keats – he had always fancied himself something of an homme de lettres. I puffed again. What was it, I wondered, that the newsboy was shouting out on Harley Street below? It was difficult to hear exactly, over the sound of Paige’s voice.

“… For if I could only restore,” Paige was explaining, “the sentence to its proper order, I know this sensation would abate at once. And that is the trouble, Doctor – when there is no proper order to be found. It happens so frequently, in English grammar – the semicolons particularly, I find.” Paige shook his head. “It is not in the sentence, Doctor,” he said. “It is in me. It is a kind of monomania; I am sure of it.”

Exposure to pseudo-psychological discourse, I wrote in Paige’s case-file. I dipped my pen again, and neatly wiped it. Prone to self-diagnosis.

“Mr Paige, Sir,” said I, as I leaned back in my chair, “I quite understand your distress. Indeed, Mr Paige, I would go so far as to suggest it is natural,” leaning back still further, “to feel so excited, when one is surrounded by supposed medical men saying this or that – one cannot know what to think. It is a cloud, Mr Paige,” I said, as I puffed once more at my cigar, “it is a cloud of ignorance, which we must daily struggle to vanquish from the battlefield” – I paused, impressively – “of medico-psychology.”

As I spoke, it were as though each one of Paige’s frail thoughts were arranged all about me in a web. Each silver-slim nerve of his brain was a thread, which I could run my finger quiveringly over, and feel pulse faintly against my own cool skin. Here, one thought diverged from another – here, one intersected. For a brief moment, I had a vision of that Greek spider in the Museum, pinned perpetually to the web’s dead centre, waiting.

“What you term monomania,” I continued, “is but a string of imperative conceptions, which one by one penetrate your mind. I repeat, Mr Paige, these are not insane thoughts. The insanity, or, should I say, the distress, arises only when you allow yourself to brood over them. Now, for your recovery, I advise a twofold treatment,” said I, taking another page from the back of my case-book. “Firstly, Mr Paige, you must strengthen your body. Take long walks – go out to the Heath, perhaps, on Sundays – and take a glass of brandy-and-water every night before bed: this will improve the flow of blood to your brain. Secondly,” continued I, “you must strengthen your mind. These imperative conceptions under which you suffer, have unbalanced the normal relation which exists in your mind between the thought and the word. You must revise thoroughly every rule of English grammar; until every word that you speak, write or read is entirely in submission to your commanding thoughts. A vital union, Mr Paige – a vital union between the thought and the word.”

“But sometimes, Doctor –” interrupted Paige.

“Take Lindley Murray, for example,” I continued, reaching for the copy of Lindley Murray’s Grammar that I kept by me during my consultations with Paige. “Let us see what we find on page – one hundred and forty-five.” I smoothed the paper down, and reversed the book to face Paige. “Here,” said I, “Socrates and Plato were wise. Now, let us parse this together – Socrates and Plato, two substantives in the proper form, joined by the copulative conjunction, and –”

“I understand how to copulate, Doctor,” said Paige. “I understand these rules! Really, Dr Moore,” said he, pushing Lindley Murray back toward me, “you must think me simple indeed, if you believe me incapable of parsing so elementary a sentence. No, Doctor,” continued Paige, “my trouble is that when I come to punctuate, all these rules of which you are so fond seem to lift quite off the page. There is no right order,” he said. “All these inconsistencies – these uncertainties – these semicolons, these hyphens, these ellipses – they are like hooks, Doctor, catching horribly into the top of my brain – just the top. I will go mad one of these days,” Paige said. He had stood from his chair, and was pacing now agitatedly about the room. “I feel it, sometimes, sitting at my desk – I feel it coming on already. For I can see it all,” he declared. “I can see what it is that I want to do, and I can see all these hooks, and I feel I am being split in two. What I long for,” said Paige, sinking back into his chair, “is for it all to simply flow. I am sure you know what I mean – that sensation of gliding that one gets when every word, and every phrase, and every sentence, have all been strung together in perfect ease. – ‘The Isles of Greece’ – this is what I always think of – those lines of Byron’s –

“‘The Isles of Greece, the Isles of Greece,

Where burning Sappho lov’d and sung.’

“Do you hear it, Doctor?” Paige asked. “All those long, liquid sounds? – those languid vowels.” Paige sighed. “I feel I am floating in a stream,” said he, “and all these sounds are washing about me; and I long to sink down to the bottom, and let that clear water wash over my face. I imagine,” he continued, closing his eyes, “I imagine lying there, against the sand, and looking up – and all the sun and the shivering trees above me would be turned to water.”

I had been paused in my note-taking while Paige spoke thus, but at this, I dipped my pen again, and wrote in my note-book, “Suicidal desire to drown himself.” I looked up, and found that Paige was peering at me suspiciously.

“That was a metaphor, Doctor,” said Paige. I sighed, impatiently, and crossed out the note.

“If you wish to strengthen your mind, Mr Paige,” said I, “you must avoid speaking in metaphors. They muddy meaning,” I said. “You must always take care to say exactly what you mean.”

“But ‘The Isles of Greece’ –” interrupted Paige.

“These Ancients do keep coming up,” said I. “I have always admired the Classics, myself. Greek and Latin, of course – as a schoolboy. And Hippocrates, at university. There is a coloured picture,” continued I, “in my drawing room, of the Acropolis set against a clear blue sea. Have you ever been to Greece, Mr Paige?” I asked.

“I have not,” said Paige.

“If you have the means this summer,” said I, “I would certainly recommend a short sojourn in Athens, or in Crete. The warm sea-air would do you good, I am sure.”

Paige had been staring at the desk rather quietly. Now, he looked up at me once more, and smiled. “I fear –” he said, “– I fear we do not quite understand each other today, Doctor.” He smiled again. “Perhaps,” he ventured, “it would be best if we were to continue this conversation next week.”

“If you think it best, Mr Paige,” said I. Paige had always been a sudden, starting sort of man, after all. “I am always happy to oblige.”

I stood up to shake Paige’s hand. There was a smudge of blue ink, I noticed, near the tip of his third finger.

“I shall see you next week, Dr Moore,” said Paige.

“Of course, Mr Paige,” said I. “I wish you a safe journey home.”

Resistant to treatment, I wrote in the case-file, as Paige closed the door. Unwilling to change.

I caught a cab home, that evening. Perhaps it would have been better to walk, but the traffic, by close of day, had churned the streets so much to mire, that the idea of that watery walk back from Harley Street sent a dampness into me. As I stood on the top step of my practice to lock the street door, I saw the wreathing sky above bruised, as it were, with yellow and purple; and for a moment, I wondered if the whole London sky were but a ream of unrolled skin, stretched out and oozing.

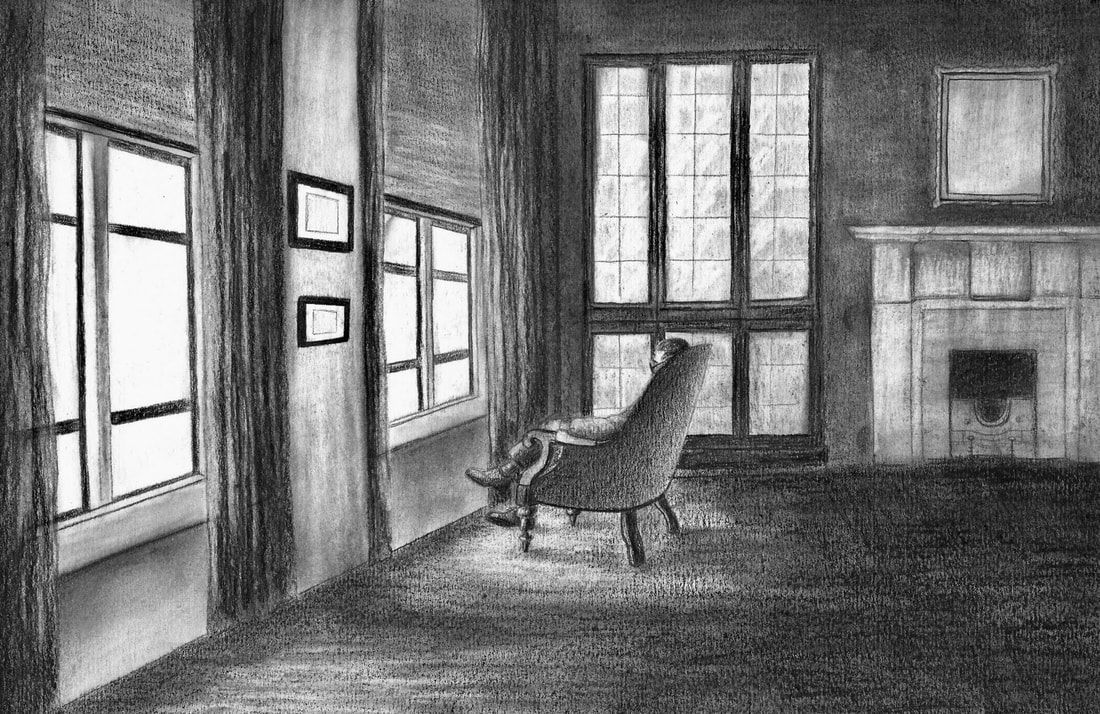

I did little, during the stale cab-ride home; and littler still, when I returned at last to my Chiltern Street lodgings. I dined early, that evening: Mrs Wallace came for my order, and brought back a plate of boiled mutton with onion sauce, and a slice of pie. I sat, afterwards, in my front-room chair by the window, and listened to the rain lash against the glass, as I cut a cigar. The curtains beside me were thick and strange. Outside, the light from the streetlamp flickered and failed as the wind danced around it; and the cold leaves blew. As the hours drew on, I heard Mrs Wallace shut the stove in the kitchen, and wipe down its lids. My watch struck ten (a minute early, as usual), and the St Stephens bell outside followed, with its ten slow chimes. I heard Mrs Wallace go into the bedroom and light the fire, and sweep around the bed once more. At last, I heard her take up her coat, and go out through the kitchen door. I was alone.

I must pause my narrative here to make a confession. It is one that I have never committed to paper, nor indeed, I own, let brush aloud over my two lips. Even now, as I sit here with my pen poised to write, I find I struggle to form the letters; to give at last, to this secret vice of mine, a material shape in black and blue (for it is dark night, as I write now, and my ink gleams strangely in the light) – I mean, in short, that I am – a Translator.

How queer to see it written down at last. That I, the man of science, the man of exactitude, soldier in the vanguard of modernity, arachnid of the web of knowledge – that I should allow myself to deal in an Art so unscientific, so inexact, so slippery, as that of Translation: an art which one cannot see or sense, but only feel one’s way into, handicapped and blind.

That is to say, that when Mrs Wallace had left, I filled my pipe, took out my desk and prepared to write. The text I was translating was a Greek work; a collection of ancient verses found engraved on the walls of a time-lost tomb in Cyprus. Though over two thousand years in age, these verses were only discovered recently, and the sole record yet in circulation is a French translation, compiled by a certain M. Louÿs. It was this French book that I held, now, in my hands; yellow-covered, with the names of the poet and translator in plain black type along the spine. At the top of a clean sheet of paper, I wrote the words, ‘Fragment 86 – The Silence of Mnasidika.’ Then, I took up the French book, and began slowly to read, pausing occasionally to move its pages closer to the light.

“Elle avait ri toute la journée,” I murmured, softly. “Et même elle s’était un peu moquée de moi …”

Off my tongue and around the room, the curves of those words shimmered and danced . I felt I lay beside a river, or else some warm sea, lying and watching the green streams as they flowed and rippled around the stones that lay beneath; around cool marble, worn smooth and round with age, or the white-ringed columns of a temple sunk beneath the waves. Slowly, those curves drew me deeper: the winking green of the surface bubbled and capped far above my head; and around me, the cool depths turned blue, and then black; gleaming invisibly with shapes and sounds I could not see. In the lamp-light, my ink was still wet against the page. I set my pen down, and read over the lines I had just written:

“She had laughed all day, and had even mocked me a little. She had refused to obey me, before several strange women.

When we returned, I affected not to speak to her, and when she flung her arms about my neck, saying: ‘Are you angry?’ I said to her:

‘O! you are no longer as you used to be, you are no longer as you were the first day. I no longer recognise you, Mnasidika.’ She did not answer me;

But she attired herself with all the jewels she had not worn for so long, and the same yellow gown embroidered in blue from the day of our first encounter.”

The ending was not quite right. The punctuation had eluded me – I had not been able to decide whether to use a comma, or a semicolon. “… For so long,” I whispered, “and the same yellow gown. The same yellow gown …”

It was in that last long compound sentence. Yet – how strange! As I looked again, I saw a comma there between the clauses – but I felt quite sure I had used a semicolon. I distinctly remembered placing a semicolon. The blue words swam like smoke before my eyes. In the closeted air, the hot breath of the fire and the dun breath from my lips hooked and swayed in queer and horrible directions. A comma, I thought. A semicolon.

For I had been taught, at school, to mark the stops by the length of time that one paused when one spoke; but here, as I attempted to read aloud, the gaps between the letters and the gaps between the words stretched and shrunk with each glance I cast upon them. Around and around those bright eyes swam. Around and around, the pale smoke gyrated. And what was the use of all those rules in Lindley Murray – seven pages of them, by my count – when at the end of it all, one is told at the end of them that one must only give an attention to “the sense of any passage” – I cast the book aside. A semicolon, I thought. A semicolon.

The words had lifted off the page now, and were gleaming in their hundreds back down at me through the thick air. For a moment, I felt the blue smoke roll over the skin of my neck, like smooth, invisible hands. The page on which I wrote was so large and white that it seemed to spill quite over my desk, and down along the floor; one pure white sheet of paper, large enough for a young girl to lie upon. And when I peered closer, it seemed that there was indeed the shape of a girl lying on the page, somewhere between the third and the fourth lines. In the light from the dying fire, her black eyes seemed to gleam strangely. Her hair was black against the page, and loose. Around her throat, and arms, and ankles glinted too many a golden ring for me to count; and I saw blue jewels against her skin, and flashing through her hair and tongue.

“Do you know what I must do?” I asked. “Have you read Lindley Murray?” The girl did not speak to me; she only reached over the page with one filagree arm, and picked up a semicolon; then she tore the dot away from the comma, and placed it in her mouth; she ate it whole. The girl swallowed. Then she turned to me to grin and I saw that her lips, and her tongue, and two fingers of her right hand all gleamed back at me with black-blue.

“What must I do?” I asked, as the girl tipped back her gleaming blue tongue, and laughed. And from my own lips, I heard the words, “Elle avait ri toute la journée, et même elle s’était un peu moquée de moi. Elle avait refusé de m’obéir …”

I woke then, with a start, to the cold ache of dawn. There was a faint pain in the lower part of my back, and I saw my pen clasped still in the fist of my hand. During the night, the ink had spilled in a pool over the page, and I could read none of the translation I had so laboured over. The room smelled stale, of cigars.

I shut my writing-desk, stretched, and began to dress, so as to make a good impression on the insane.

Friday, 22nd of March, 1895. Well – rather a long pause between the last entry and this. My work, it seems, has been preying on my mind. But! not to worry – I shall not let it consume me overmuch; I shall instead occupy these last few hours of the night in the bringing of this little record au courant.

Yesterday was a dull, wet, blustery sort of a day – the very worst of March. The rain, it is true, abated somewhat in the afternoon; yet it did not seem so, for the damp of the morning loomed heavily in the air. I believe that fog must have settled into my mind; for I had the impression, as I sat by my window on Harley Street, that the Thames, swollen brimful with rain, and unable to hold one drop further of water, had spilled its yellow-brown contents back up into the sky; thus creating those wreaths of yellow fog that all the men and horses passing by on Harley Street appeared to wade through. So heavy was this rain-light, that it cast a yellow shadow over the skin of the hand with which I wrote, and over my pale lined paper. I recollect an intense stillness: the sound of my pen scratching (I had not yet mended the nib), and the low drone of my client’s voice, against the patter of the rain and the wind outside – all else was muffled. But the room was neat – the board floor neatly scrubbed; the walls well-papered; my map of the brain and my old phrenologist’s skull dusted by Mrs Bechdel that morning (she comes Tuesdays and Thursdays, now). I glanced back down to my client’s case-file, and dipped my pen once more; the case-file, which I reproduce here, read as follows: –

John Paige, m., 32. Single. Present occupation: Clerk at Enos Batley & Co., Publishers – four days per week, only. Of the usual size and build; dark hair, dark eyes. Of usual means. No history of hereditary insanity; but neuro-degenerate taint (?) on the side of the mother (widowed 1879, remarried June 1880). Weak of body, and much addicted to self-abuse. Suffers from a pathological obsession with English grammar and orthography, viz., usage of semicolons vs. commas, periods, colons –

“Doctor?” enquired my client. I glanced up from the file. Mr Paige was gazing at me, with a countenance expressive of great earnestness. “Dr Moore, Sir,” my client repeated, “would you say that you agree?”

“Yes, quite,” said I. “Yes, Mr Paige, I believe you are correct.” I had not heard what Paige had said – it was that accursed rain, of course, blotting out every sound. “Do continue, Mr Paige,” I said.

Paige sighed, deeply. “You see, Doctor,” said he, “it is my work that is the trouble. Being in my line of business, of course, grappling with these words at all hours of the day – one cannot very well avoid it.”

“No,” said I. “No, naturally.”

“But it does not feel like a thought, Doctor.” (Paige was rather fond of italics). “It feels – how can I describe it?” Paige paused. “I feel it physically,” he said at last, decidedly. “It is a physical sensation. When I read a sentence with a semicolon misplaced, I feel a queer consciousness of every hair standing up on the top of my head – just the top – and I hate it! it tickles so.”

I opened a desk-drawer and took out a Trichonopoly. “Have you a hat to wear, Mr Paige?” asked I, as I reached for my matchbox.

“Not indoors, Doctor,” said Paige.

“A good tight hat is the best way to go.” Paige said something in reply; I did not hear. I wrote discreetly in his case-file: Somatic delusion relating to top of head. I took a long puff of my cigar.

There was something of a flush about Paige’s cheeks, as he spoke. His gesticulations – mild, at first – grew more violent as he progressed in his speech; and the pink spots on either cheek deepened correspondingly. It was a symptom, I reflected, as I watched the dun cigar-smoke cloud the air. To the man of science – and I trusted I might count myself as such – it was a clear symptom of that crude overexcitement which leads so many sane men down the black path of madness; the kind of case one might publish, perhaps, if one could only sort out one’s notes. The brown smoke before me was beginning to settle somewhat. Yet honesty must be sought, of course; honesty, above all. And I feared that Paige actually deepened this flush artificially, through pinching, perhaps, or some other such means; in imitation of that portrait of Keats – he had always fancied himself something of an homme de lettres. I puffed again. What was it, I wondered, that the newsboy was shouting out on Harley Street below? It was difficult to hear exactly, over the sound of Paige’s voice.

“… For if I could only restore,” Paige was explaining, “the sentence to its proper order, I know this sensation would abate at once. And that is the trouble, Doctor – when there is no proper order to be found. It happens so frequently, in English grammar – the semicolons particularly, I find.” Paige shook his head. “It is not in the sentence, Doctor,” he said. “It is in me. It is a kind of monomania; I am sure of it.”

Exposure to pseudo-psychological discourse, I wrote in Paige’s case-file. I dipped my pen again, and neatly wiped it. Prone to self-diagnosis.

“Mr Paige, Sir,” said I, as I leaned back in my chair, “I quite understand your distress. Indeed, Mr Paige, I would go so far as to suggest it is natural,” leaning back still further, “to feel so excited, when one is surrounded by supposed medical men saying this or that – one cannot know what to think. It is a cloud, Mr Paige,” I said, as I puffed once more at my cigar, “it is a cloud of ignorance, which we must daily struggle to vanquish from the battlefield” – I paused, impressively – “of medico-psychology.”

As I spoke, it were as though each one of Paige’s frail thoughts were arranged all about me in a web. Each silver-slim nerve of his brain was a thread, which I could run my finger quiveringly over, and feel pulse faintly against my own cool skin. Here, one thought diverged from another – here, one intersected. For a brief moment, I had a vision of that Greek spider in the Museum, pinned perpetually to the web’s dead centre, waiting.

“What you term monomania,” I continued, “is but a string of imperative conceptions, which one by one penetrate your mind. I repeat, Mr Paige, these are not insane thoughts. The insanity, or, should I say, the distress, arises only when you allow yourself to brood over them. Now, for your recovery, I advise a twofold treatment,” said I, taking another page from the back of my case-book. “Firstly, Mr Paige, you must strengthen your body. Take long walks – go out to the Heath, perhaps, on Sundays – and take a glass of brandy-and-water every night before bed: this will improve the flow of blood to your brain. Secondly,” continued I, “you must strengthen your mind. These imperative conceptions under which you suffer, have unbalanced the normal relation which exists in your mind between the thought and the word. You must revise thoroughly every rule of English grammar; until every word that you speak, write or read is entirely in submission to your commanding thoughts. A vital union, Mr Paige – a vital union between the thought and the word.”

“But sometimes, Doctor –” interrupted Paige.

“Take Lindley Murray, for example,” I continued, reaching for the copy of Lindley Murray’s Grammar that I kept by me during my consultations with Paige. “Let us see what we find on page – one hundred and forty-five.” I smoothed the paper down, and reversed the book to face Paige. “Here,” said I, “Socrates and Plato were wise. Now, let us parse this together – Socrates and Plato, two substantives in the proper form, joined by the copulative conjunction, and –”

“I understand how to copulate, Doctor,” said Paige. “I understand these rules! Really, Dr Moore,” said he, pushing Lindley Murray back toward me, “you must think me simple indeed, if you believe me incapable of parsing so elementary a sentence. No, Doctor,” continued Paige, “my trouble is that when I come to punctuate, all these rules of which you are so fond seem to lift quite off the page. There is no right order,” he said. “All these inconsistencies – these uncertainties – these semicolons, these hyphens, these ellipses – they are like hooks, Doctor, catching horribly into the top of my brain – just the top. I will go mad one of these days,” Paige said. He had stood from his chair, and was pacing now agitatedly about the room. “I feel it, sometimes, sitting at my desk – I feel it coming on already. For I can see it all,” he declared. “I can see what it is that I want to do, and I can see all these hooks, and I feel I am being split in two. What I long for,” said Paige, sinking back into his chair, “is for it all to simply flow. I am sure you know what I mean – that sensation of gliding that one gets when every word, and every phrase, and every sentence, have all been strung together in perfect ease. – ‘The Isles of Greece’ – this is what I always think of – those lines of Byron’s –

“‘The Isles of Greece, the Isles of Greece,

Where burning Sappho lov’d and sung.’

“Do you hear it, Doctor?” Paige asked. “All those long, liquid sounds? – those languid vowels.” Paige sighed. “I feel I am floating in a stream,” said he, “and all these sounds are washing about me; and I long to sink down to the bottom, and let that clear water wash over my face. I imagine,” he continued, closing his eyes, “I imagine lying there, against the sand, and looking up – and all the sun and the shivering trees above me would be turned to water.”

I had been paused in my note-taking while Paige spoke thus, but at this, I dipped my pen again, and wrote in my note-book, “Suicidal desire to drown himself.” I looked up, and found that Paige was peering at me suspiciously.

“That was a metaphor, Doctor,” said Paige. I sighed, impatiently, and crossed out the note.

“If you wish to strengthen your mind, Mr Paige,” said I, “you must avoid speaking in metaphors. They muddy meaning,” I said. “You must always take care to say exactly what you mean.”

“But ‘The Isles of Greece’ –” interrupted Paige.

“These Ancients do keep coming up,” said I. “I have always admired the Classics, myself. Greek and Latin, of course – as a schoolboy. And Hippocrates, at university. There is a coloured picture,” continued I, “in my drawing room, of the Acropolis set against a clear blue sea. Have you ever been to Greece, Mr Paige?” I asked.

“I have not,” said Paige.

“If you have the means this summer,” said I, “I would certainly recommend a short sojourn in Athens, or in Crete. The warm sea-air would do you good, I am sure.”

Paige had been staring at the desk rather quietly. Now, he looked up at me once more, and smiled. “I fear –” he said, “– I fear we do not quite understand each other today, Doctor.” He smiled again. “Perhaps,” he ventured, “it would be best if we were to continue this conversation next week.”

“If you think it best, Mr Paige,” said I. Paige had always been a sudden, starting sort of man, after all. “I am always happy to oblige.”

I stood up to shake Paige’s hand. There was a smudge of blue ink, I noticed, near the tip of his third finger.

“I shall see you next week, Dr Moore,” said Paige.

“Of course, Mr Paige,” said I. “I wish you a safe journey home.”

Resistant to treatment, I wrote in the case-file, as Paige closed the door. Unwilling to change.

I caught a cab home, that evening. Perhaps it would have been better to walk, but the traffic, by close of day, had churned the streets so much to mire, that the idea of that watery walk back from Harley Street sent a dampness into me. As I stood on the top step of my practice to lock the street door, I saw the wreathing sky above bruised, as it were, with yellow and purple; and for a moment, I wondered if the whole London sky were but a ream of unrolled skin, stretched out and oozing.

I did little, during the stale cab-ride home; and littler still, when I returned at last to my Chiltern Street lodgings. I dined early, that evening: Mrs Wallace came for my order, and brought back a plate of boiled mutton with onion sauce, and a slice of pie. I sat, afterwards, in my front-room chair by the window, and listened to the rain lash against the glass, as I cut a cigar. The curtains beside me were thick and strange. Outside, the light from the streetlamp flickered and failed as the wind danced around it; and the cold leaves blew. As the hours drew on, I heard Mrs Wallace shut the stove in the kitchen, and wipe down its lids. My watch struck ten (a minute early, as usual), and the St Stephens bell outside followed, with its ten slow chimes. I heard Mrs Wallace go into the bedroom and light the fire, and sweep around the bed once more. At last, I heard her take up her coat, and go out through the kitchen door. I was alone.

I must pause my narrative here to make a confession. It is one that I have never committed to paper, nor indeed, I own, let brush aloud over my two lips. Even now, as I sit here with my pen poised to write, I find I struggle to form the letters; to give at last, to this secret vice of mine, a material shape in black and blue (for it is dark night, as I write now, and my ink gleams strangely in the light) – I mean, in short, that I am – a Translator.

How queer to see it written down at last. That I, the man of science, the man of exactitude, soldier in the vanguard of modernity, arachnid of the web of knowledge – that I should allow myself to deal in an Art so unscientific, so inexact, so slippery, as that of Translation: an art which one cannot see or sense, but only feel one’s way into, handicapped and blind.

That is to say, that when Mrs Wallace had left, I filled my pipe, took out my desk and prepared to write. The text I was translating was a Greek work; a collection of ancient verses found engraved on the walls of a time-lost tomb in Cyprus. Though over two thousand years in age, these verses were only discovered recently, and the sole record yet in circulation is a French translation, compiled by a certain M. Louÿs. It was this French book that I held, now, in my hands; yellow-covered, with the names of the poet and translator in plain black type along the spine. At the top of a clean sheet of paper, I wrote the words, ‘Fragment 86 – The Silence of Mnasidika.’ Then, I took up the French book, and began slowly to read, pausing occasionally to move its pages closer to the light.

“Elle avait ri toute la journée,” I murmured, softly. “Et même elle s’était un peu moquée de moi …”

Off my tongue and around the room, the curves of those words shimmered and danced . I felt I lay beside a river, or else some warm sea, lying and watching the green streams as they flowed and rippled around the stones that lay beneath; around cool marble, worn smooth and round with age, or the white-ringed columns of a temple sunk beneath the waves. Slowly, those curves drew me deeper: the winking green of the surface bubbled and capped far above my head; and around me, the cool depths turned blue, and then black; gleaming invisibly with shapes and sounds I could not see. In the lamp-light, my ink was still wet against the page. I set my pen down, and read over the lines I had just written:

“She had laughed all day, and had even mocked me a little. She had refused to obey me, before several strange women.

When we returned, I affected not to speak to her, and when she flung her arms about my neck, saying: ‘Are you angry?’ I said to her:

‘O! you are no longer as you used to be, you are no longer as you were the first day. I no longer recognise you, Mnasidika.’ She did not answer me;

But she attired herself with all the jewels she had not worn for so long, and the same yellow gown embroidered in blue from the day of our first encounter.”

The ending was not quite right. The punctuation had eluded me – I had not been able to decide whether to use a comma, or a semicolon. “… For so long,” I whispered, “and the same yellow gown. The same yellow gown …”

It was in that last long compound sentence. Yet – how strange! As I looked again, I saw a comma there between the clauses – but I felt quite sure I had used a semicolon. I distinctly remembered placing a semicolon. The blue words swam like smoke before my eyes. In the closeted air, the hot breath of the fire and the dun breath from my lips hooked and swayed in queer and horrible directions. A comma, I thought. A semicolon.

For I had been taught, at school, to mark the stops by the length of time that one paused when one spoke; but here, as I attempted to read aloud, the gaps between the letters and the gaps between the words stretched and shrunk with each glance I cast upon them. Around and around those bright eyes swam. Around and around, the pale smoke gyrated. And what was the use of all those rules in Lindley Murray – seven pages of them, by my count – when at the end of it all, one is told at the end of them that one must only give an attention to “the sense of any passage” – I cast the book aside. A semicolon, I thought. A semicolon.

The words had lifted off the page now, and were gleaming in their hundreds back down at me through the thick air. For a moment, I felt the blue smoke roll over the skin of my neck, like smooth, invisible hands. The page on which I wrote was so large and white that it seemed to spill quite over my desk, and down along the floor; one pure white sheet of paper, large enough for a young girl to lie upon. And when I peered closer, it seemed that there was indeed the shape of a girl lying on the page, somewhere between the third and the fourth lines. In the light from the dying fire, her black eyes seemed to gleam strangely. Her hair was black against the page, and loose. Around her throat, and arms, and ankles glinted too many a golden ring for me to count; and I saw blue jewels against her skin, and flashing through her hair and tongue.

“Do you know what I must do?” I asked. “Have you read Lindley Murray?” The girl did not speak to me; she only reached over the page with one filagree arm, and picked up a semicolon; then she tore the dot away from the comma, and placed it in her mouth; she ate it whole. The girl swallowed. Then she turned to me to grin and I saw that her lips, and her tongue, and two fingers of her right hand all gleamed back at me with black-blue.

“What must I do?” I asked, as the girl tipped back her gleaming blue tongue, and laughed. And from my own lips, I heard the words, “Elle avait ri toute la journée, et même elle s’était un peu moquée de moi. Elle avait refusé de m’obéir …”

I woke then, with a start, to the cold ache of dawn. There was a faint pain in the lower part of my back, and I saw my pen clasped still in the fist of my hand. During the night, the ink had spilled in a pool over the page, and I could read none of the translation I had so laboured over. The room smelled stale, of cigars.

I shut my writing-desk, stretched, and began to dress, so as to make a good impression on the insane.

– T. Moore

Orana Loren lives on Gadigal country in Sydney, Australia. She currently studies English Literature at the University of Sydney. Orana's fiction spans the genres of magical realism, historical fiction, and surrealism; and often touches on themes of madness, dreaming, and sapphic desire. For her non-fiction writing, Orana was named the joint winner of the University of Sydney's 2022 Beauchamp Prize.