BLUE SKY LANGUAGE

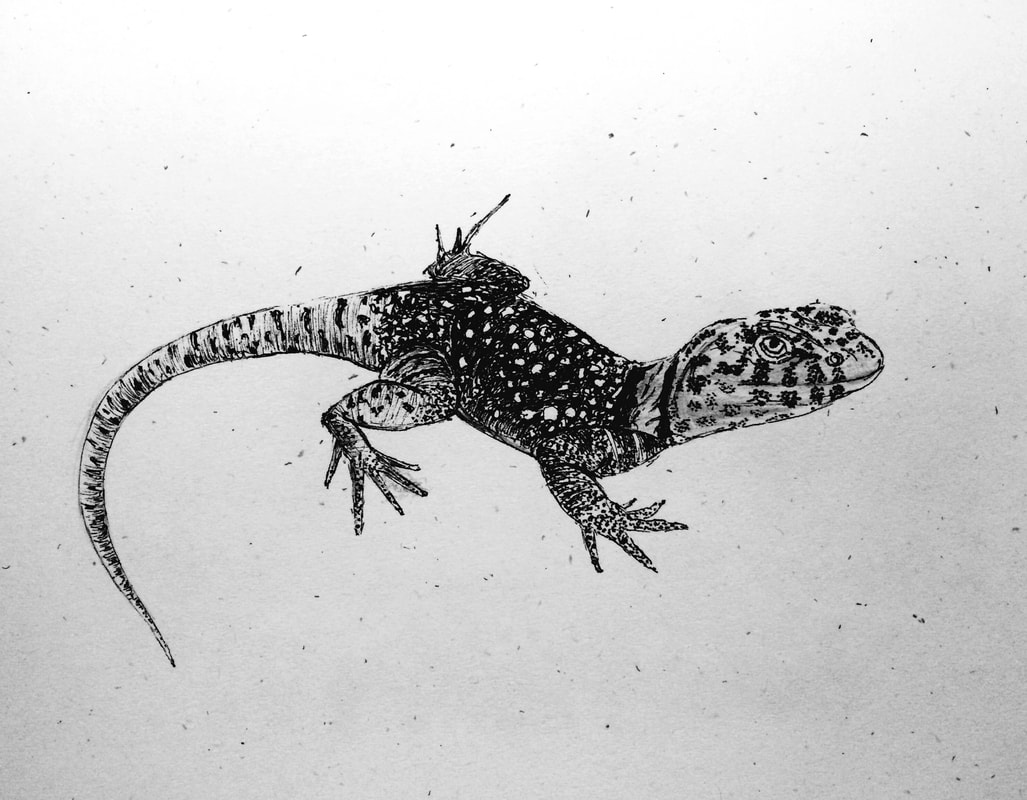

There is guilt. I found the drying body of a blue-collared lizard in a cleft of sandstone. I was not the one who killed it. It was already dead when I found it. I stood vigil with the lizard under the sun - lone standing mesas scattered across sage flats, long shadows across sand. The ghost of the lizard followed me home. I am not saying this from inside a dream.

There is joy. Sometimes, the lizard's ghost speaks into my left ear in a language that can only be described as various shades of blue. It is a language of unbearable beauty, of the blue sky itself – the language of the eye, roving from east to west, horizon to horizon. I am not saying this from inside a dream, I whisper those blue words into holes in stone every chance I get.

There is death. A blue-collared lizard sits on a low stone wall, stares at me. Sun on his back, he wants to transmute stone into skin, skin into stone. I say: "I'm sorry, but I did not kill him." I know this has nothing to do with this moment, this lizard. I am insisting on my innocence for things that I have not done because of all the things I have. I am not saying this from inside a dream; I too, want to transmute stone into skin and skin into stone.

There is joy. Sometimes, the lizard's ghost speaks into my left ear in a language that can only be described as various shades of blue. It is a language of unbearable beauty, of the blue sky itself – the language of the eye, roving from east to west, horizon to horizon. I am not saying this from inside a dream, I whisper those blue words into holes in stone every chance I get.

There is death. A blue-collared lizard sits on a low stone wall, stares at me. Sun on his back, he wants to transmute stone into skin, skin into stone. I say: "I'm sorry, but I did not kill him." I know this has nothing to do with this moment, this lizard. I am insisting on my innocence for things that I have not done because of all the things I have. I am not saying this from inside a dream; I too, want to transmute stone into skin and skin into stone.

GRAND CANYON

I hit a traffic jam a couple miles out from the Desert View Visitor Center. When I finally reached the center’s parking lot, the car was overheating. I found a parking space, thinking I’d hang out for a while, let the car cool down. There was a cafeteria, a gift shop. And people, so many people. I wandered down to an old stone tower that had a view of the southern half of the canyon. The scene had no effect. I felt I was in a theater, watching a movie of the Grand Canyon. The only way I can be saying this is from deep inside a dream - how else?

Dejected, I sat down at the edge of the parking lot, about ten feet from an edge with no railing, beneath a dead tree. The bleached branches stretched out into space. A couple of families stood about two feet from the edge, talking, laughing. They obviously were traveling together. The boys kept pretending to push each other over the edge. A girl that looked like she belonged to one of the families – eleven, twelve – stood near the tree, eating an ice cream, eyeing the boys with disgust. She eventually turned her back on them. You can see how all this was taking place inside a dream.

A raven landed on one of the branches above me, focused on the cone in the girl's hand, then lifted off – a huge pterodactyl shadow in the dust below – and floated over her head. The girl looked up at the bird, screamed, and fell backwards, towards the cliff edge. The raven plucked up what was left of the cone and flew off. The girl started to cry, hysterical. Inside the dream, a mother ran up, comforted her. The boys smirked, inside the dream.

It was clear she wasn’t crying about the raven or the lost cone or the pain from the tumble. Even though she was at least ten feet away from the rim, I know that for a second, as she fell to the ground, she thought she was about to fly out into that vast space. Listening to the panic in her cries, I suddenly saw it, felt it – the fantastic terror of the drop. All my organs rose toward my throat, toward my own scream, and I knew that if I got up, ran towards the edge, threw myself over, I would fall for centuries, past the jagged levels of stone, exposed by floods 70 million years gone, to be reborn as a black feather resting in the eye socket of a mule skull.

Dejected, I sat down at the edge of the parking lot, about ten feet from an edge with no railing, beneath a dead tree. The bleached branches stretched out into space. A couple of families stood about two feet from the edge, talking, laughing. They obviously were traveling together. The boys kept pretending to push each other over the edge. A girl that looked like she belonged to one of the families – eleven, twelve – stood near the tree, eating an ice cream, eyeing the boys with disgust. She eventually turned her back on them. You can see how all this was taking place inside a dream.

A raven landed on one of the branches above me, focused on the cone in the girl's hand, then lifted off – a huge pterodactyl shadow in the dust below – and floated over her head. The girl looked up at the bird, screamed, and fell backwards, towards the cliff edge. The raven plucked up what was left of the cone and flew off. The girl started to cry, hysterical. Inside the dream, a mother ran up, comforted her. The boys smirked, inside the dream.

It was clear she wasn’t crying about the raven or the lost cone or the pain from the tumble. Even though she was at least ten feet away from the rim, I know that for a second, as she fell to the ground, she thought she was about to fly out into that vast space. Listening to the panic in her cries, I suddenly saw it, felt it – the fantastic terror of the drop. All my organs rose toward my throat, toward my own scream, and I knew that if I got up, ran towards the edge, threw myself over, I would fall for centuries, past the jagged levels of stone, exposed by floods 70 million years gone, to be reborn as a black feather resting in the eye socket of a mule skull.

CHATTER

A yellow school bus passes. All the figures inside are wearing orange jumpsuits, black hoods. This is the fashion. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I have heard cries rising up from beneath the floorboards near dawn.

In the plaza, an old man suddenly turned, looked behind him, his eyes full of fear, as if he’d seen a ghost. I scanned the crowd, trying to see what he’d seen. I saw people with shopping bags, sitting on benches, enjoying the sun, talking on their phones. Chatter between satellites, business as usual. But he saw something, I know he did. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I have cut the lines between cause and effect into my skin with the edge of a black aspen leaf.

Today, the man who usually hawks newspapers on the hospital road is handing out stones. I am not saying this from inside a dream. A crushed black snake on the road’s shoulder stirs, slips into high grass (Another dead soldier; another dead civilian; both trying to be seen). I am not saying this from inside a dream. Drop sage-dust into an open flame, it sparks like gunpowder.

In the plaza, an old man suddenly turned, looked behind him, his eyes full of fear, as if he’d seen a ghost. I scanned the crowd, trying to see what he’d seen. I saw people with shopping bags, sitting on benches, enjoying the sun, talking on their phones. Chatter between satellites, business as usual. But he saw something, I know he did. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I have cut the lines between cause and effect into my skin with the edge of a black aspen leaf.

Today, the man who usually hawks newspapers on the hospital road is handing out stones. I am not saying this from inside a dream. A crushed black snake on the road’s shoulder stirs, slips into high grass (Another dead soldier; another dead civilian; both trying to be seen). I am not saying this from inside a dream. Drop sage-dust into an open flame, it sparks like gunpowder.

LAUNDROMAT

I watch an old woman load a washer. When she’s done, she sits next to me, hands in her lap, head down. I hear a voice inside me say: “You are a shoe buried in snow.” Then: “The old lady is the bird that never finds the shoe buried in snow.” The voice sounds like my dead cousin Sophia. She was always saying things like that. I'm telling you this from inside a dream.

A four-year-old boy follows his father through the glass doors, breaks off to the video game console next to the soap dispenser, pushing buttons, swinging the joystick back and forth. The father loads a washer, sits down on the other side of the old woman, and pulls out his cell phone. Sophia snickers: “He is young enough to believe that this is not where he will be in twenty years. You thought the same, didn’t you?” Sophia talks to me from the inside of the inside of a dream. It's all very meta.

I stand, stretch, and wander down the long wall of dryers to the bathroom. Inside, I run the water, read the writing on the wall. I’m not here to do laundry. I have no laundry. I’m just marking time, trying to keep warm. When I finally open the door, step out, I see the old woman is still staring down at the floor, hands in her lap. What can she possibly be thinking? Whatever it is, it is happening from inside a dream…so, who cares?

“No matter what the old woman is thinking,” Sophia says, “beneath those thoughts she is occupied by what will never happen, what can never be attained.”

A four-year-old boy follows his father through the glass doors, breaks off to the video game console next to the soap dispenser, pushing buttons, swinging the joystick back and forth. The father loads a washer, sits down on the other side of the old woman, and pulls out his cell phone. Sophia snickers: “He is young enough to believe that this is not where he will be in twenty years. You thought the same, didn’t you?” Sophia talks to me from the inside of the inside of a dream. It's all very meta.

I stand, stretch, and wander down the long wall of dryers to the bathroom. Inside, I run the water, read the writing on the wall. I’m not here to do laundry. I have no laundry. I’m just marking time, trying to keep warm. When I finally open the door, step out, I see the old woman is still staring down at the floor, hands in her lap. What can she possibly be thinking? Whatever it is, it is happening from inside a dream…so, who cares?

“No matter what the old woman is thinking,” Sophia says, “beneath those thoughts she is occupied by what will never happen, what can never be attained.”

GOOD GUYS, BAD GUYS

A short burst of the freight train’s horn arcs over me. There is a stuffed lynx in a glass box down the road, in a restaurant in Ely. There are photos of actors from nineteen thirties westerns on the restaurant wall. Some wear black hats, some wear white. There are tiny, anonymous graves scattered all over this desert. I am not saying this from inside a dream. Coyotes paw at my door all night long, trying to get in.

Out here, drones hover behind the brilliant sun, practicing for the second coming. There are lights that move across the night sky, soaking up the darkness between the stars. No one knows what those lights are, what they might mean. I have seen the men who search the sand with metal detectors, getting down on all fours, desperate to find pieces of the one, true secret; the hidden center that will destroy all lies. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I can see the vulture’s shadow – a sudden cross – briefly animate the stone in my hand.

From the radio: “They dropped food on the good guys and bombs on the bad guys!” A child’s vision. This is the season of the enemy’s tongue pressed into a scrap book for safe keeping. Good guys, bad guys. This is the season of a lynx fur stole resting on a glass box containing a stuffed lynx. Good guys, bad guys. This is the season of fingers found inside envelopes on the side of the road. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I've lit my car on fire as a beacon.

Out here, drones hover behind the brilliant sun, practicing for the second coming. There are lights that move across the night sky, soaking up the darkness between the stars. No one knows what those lights are, what they might mean. I have seen the men who search the sand with metal detectors, getting down on all fours, desperate to find pieces of the one, true secret; the hidden center that will destroy all lies. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I can see the vulture’s shadow – a sudden cross – briefly animate the stone in my hand.

From the radio: “They dropped food on the good guys and bombs on the bad guys!” A child’s vision. This is the season of the enemy’s tongue pressed into a scrap book for safe keeping. Good guys, bad guys. This is the season of a lynx fur stole resting on a glass box containing a stuffed lynx. Good guys, bad guys. This is the season of fingers found inside envelopes on the side of the road. I am not saying this from inside a dream. I've lit my car on fire as a beacon.

INSIDE THE CAVE

I woke in the middle of the night, unable to breathe, heard someone whisper a ten-thousand-year old spell in the dark. I am telling you this from inside a dream.

I dressed, went down to the switch tracks behind the commuter station at the end of the street, waited for the Amtrak and Union Pacific lines to pass each other in the fog. I stepped between the two rail lines.

When the first train passed - Amtrak - the noise was extravagant, absorbing my ears eyes, body, mind. When the second train passed - Union Pacific - and I was sandwiched between the screaming walls of steel I was so terrified I closed my eyes. If I had moved forward an inch, or back an inch, I knew I was dead, scattered into the dark. Remember, I am saying this from inside a dream.

When I summoned the courage to open my eyes, I saw immense shadows moving across the steel wall shooting by: Baal, Lamia, Tlaloc, Abyzou, all the vicious child-eaters of the night world, copulating and blending with all of us, a panoply of death and transformation, producing something new.

And I realized I was the torch-bearer, the first inside a new kind of cave. Like the boys who’d stumbled into Lascaux, suddenly witness to dim shapes that had been stalking them for forty thousand years. I am saying this, over and over, from inside a beautiful dream of the future.

And I carefully raised my shaking hands in praise. I raised my hands in praise.

I dressed, went down to the switch tracks behind the commuter station at the end of the street, waited for the Amtrak and Union Pacific lines to pass each other in the fog. I stepped between the two rail lines.

When the first train passed - Amtrak - the noise was extravagant, absorbing my ears eyes, body, mind. When the second train passed - Union Pacific - and I was sandwiched between the screaming walls of steel I was so terrified I closed my eyes. If I had moved forward an inch, or back an inch, I knew I was dead, scattered into the dark. Remember, I am saying this from inside a dream.

When I summoned the courage to open my eyes, I saw immense shadows moving across the steel wall shooting by: Baal, Lamia, Tlaloc, Abyzou, all the vicious child-eaters of the night world, copulating and blending with all of us, a panoply of death and transformation, producing something new.

And I realized I was the torch-bearer, the first inside a new kind of cave. Like the boys who’d stumbled into Lascaux, suddenly witness to dim shapes that had been stalking them for forty thousand years. I am saying this, over and over, from inside a beautiful dream of the future.

And I carefully raised my shaking hands in praise. I raised my hands in praise.

DOLLARS

This is what I saw:

An old woman rested on a mattress of dollars, watched wind and light sneak through a crack in the shack boards above her feet. She got up, crossed to a pile of dollars in the corner of the dark room. Chickens out in the yard clucked, scratched. She pulled a few bills from the pile, dipped them in a bowl of rust-colored water, pasted them across the crack of light in the wall. The wind pushed against the wet bills as they slowly dried.

I am telling you this from inside a dream.

Outside, she looked east. The sun was rising above the edge of a flat plain. She opened the wire mesh gate of the chicken coop, knelt in the dust, pulled some dollars from her pocket, tore them into tiny pieces. The chickens gathered around her. She told them the story the way her mother had told her.

I am not telling you this from inside a dream.

“Dollars bred dollars,” she said, “until there were too many. They clogged every room, every closet, every bed. No one could breathe. People clawed through the dollars, toward their windows. And the windows burst with dollars.” The chickens pecked at the bits of paper scattering in the wind. “People in the streets pushed and shoved each other,” she said, “shouting for joy, clutching at the rain of dollars, stuffing bills into their pockets, growing heavy with the laughter of so many dollars.”

I am telling you this from inside a dream.

“Dollars flooded the fields,” she said, “washed down into the ditches. Mama and her family ran outside, dancing. And the dollars descended, whirling over everything just as it was promised...”

The old woman finished dropping the pieces of paper and struggled to her feet. “And that’s how the world was made,” she whispered. Everything loose in the yard flapped softly.

I am not telling you this from inside a dream.

An old woman rested on a mattress of dollars, watched wind and light sneak through a crack in the shack boards above her feet. She got up, crossed to a pile of dollars in the corner of the dark room. Chickens out in the yard clucked, scratched. She pulled a few bills from the pile, dipped them in a bowl of rust-colored water, pasted them across the crack of light in the wall. The wind pushed against the wet bills as they slowly dried.

I am telling you this from inside a dream.

Outside, she looked east. The sun was rising above the edge of a flat plain. She opened the wire mesh gate of the chicken coop, knelt in the dust, pulled some dollars from her pocket, tore them into tiny pieces. The chickens gathered around her. She told them the story the way her mother had told her.

I am not telling you this from inside a dream.

“Dollars bred dollars,” she said, “until there were too many. They clogged every room, every closet, every bed. No one could breathe. People clawed through the dollars, toward their windows. And the windows burst with dollars.” The chickens pecked at the bits of paper scattering in the wind. “People in the streets pushed and shoved each other,” she said, “shouting for joy, clutching at the rain of dollars, stuffing bills into their pockets, growing heavy with the laughter of so many dollars.”

I am telling you this from inside a dream.

“Dollars flooded the fields,” she said, “washed down into the ditches. Mama and her family ran outside, dancing. And the dollars descended, whirling over everything just as it was promised...”

The old woman finished dropping the pieces of paper and struggled to her feet. “And that’s how the world was made,” she whispered. Everything loose in the yard flapped softly.

I am not telling you this from inside a dream.

Christien Gholson is the author of two books of poetry: On the Side of the Crow (Hanging Loose Press) and All the Beautiful Dead (Bitter Oleander Press; winner of the Bitter Oleander Poetry Award and finalist for the NM book award); along with a novel, A Fish Trapped Inside the Wind (Parthian Books). A long eco-poem, Tidal Flats, was published as Issue 63 of Mudlark. He was once a fish falling from the sky. He is now a black feather skipping across the desert floor. He lives in New Mexico. He can be found at: http://christiengholson.blogspot.com/.