A drop of water hung from the tree where the leaf should have been. It dangled, swelled, and then split.

There, in that moment, it became irreversible: this snow would not last forever. The world could not sustain it. And though it all seemed solid—the branches, our faces, and even the sky—I felt the shudder of this notion pass through me, with determined certainty, until it owned me.

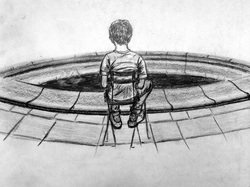

My father’s moans exploded in distinct bursts. As his sobs shook the flakes around his shoulders, he seemed to shimmer in a white haze, as if reality itself had relented around his figure and created a cushion—as though the world were sorry that my mother lay beneath the ground as he stood above it. I wonder now how she would have painted the scene: he behind me, with his heavy hands on my shoulders, and then my small silhouette, shadowed inside his, and then herself—extending from our feet in a rectangular plot, lost somewhere beneath the snow and the fresh brown stubble. She would not paint the dirt, I thought, not the coffin but her dress, white, and cotton, and she would not paint the wooden clasp but instead her hands, neat and folded, poised for an endless formality—her fingers no longer speckled in purple, her palms no longer dashed in blue.

(They will put the stone here—he had said—and don’t stand here—she is sleeping—and soon the grass will grow, on this mound of dirt—and then we’ll know her from the stone. Soon the grass will grow, soon, and then it won’t look so new but how do I know it will always feel like this?)

Or perhaps she would have painted something else entirely—herself standing next to us, and they beneath the ground instead of her. She would paint exactly what they didn’t want her to paint: something unreal and yet entirely possible. And then they would put her in the ground, and still, she would paint exactly this.

It was that they had been after, that glimmer of self-assertion that beat in her blood and burst from her hands like magic. To them, she was not the color of flowers in the moonlight and the fresh scent of birdseed at the door, the sparkling red of a ripe tomato, the cooling sweep of a wedding band as they closed their eyes for bed…she was not a voice that rode on waves, rising and falling before pausing, painting and eating before sleeping. No, they buried a body of something else, of accusations they littered against her name: 42 censored pamphlets, 18 smuggled paintings, 14 demonstrations, hundreds of exhortations for revolution, thousands of wails for a return of color.

(She would have smirked, I thought, as she finally understood: she might rest, but now they never would.)

I shivered as a gust of wind blew at my side, striking me from the space where she might have been standing. At my feet, the mound of dirt was slowly covered with white. I imagined the snow seeping through the cracks in her coffin, trickling onto her face, smoothing her wrinkles away until she was the young woman I had never known.

I slept in my father's bed that night, and marveled that he breathed, and that he continued to breathe all through the night.

***

I open the door that connects our bedroom to the studio. My mother’s brushes still stare back at me, stuffed haphazardly into an empty paint can and fanned out against the window. As the sun rises, they look like a medley of tousled heads, gleaming colors that fray the edges of the nighttime until it becomes the iridescent day. And I think, maybe today my mother will come home…

And then there she is, knocking at our door! I rush to open it. But it is only the uniformed officers; they have come instead, with their pressed blue suits and their ironed hats.

Soon, my father too is awake, and they are around us. They shuffle through our studio, upturning boxes and spilling tools onto the floor. When they squat and sift through the roughage, they look like boys in creased trousers, digging for marbles in the sand; when they stand and arch their backs, surveying their progress, they look like men. They work as a flawless unit. Even in the near-darkness of the studio, they move in perfectly choreographed cycles, dragging their shadows behind them like feathers—or capes, that flutter behind them, waving and dancing in the firelight.

My father looks like a mouse trapped in an array of circling metal gears. His wide shoulders are hunched into his jacket, and his fists are plunged deep into his pockets. He stands completely still, save for the occasional glance at me, and the consistent gaze at the door. I don't know if he sees either of these things. His eyes look dead, glassy. They contain nothing of the soft brown rings that remind me of planets and love.

He coughs.

The officers all look up for a moment, pause like dangling puppets, but in an instant they animate again. They return to their cycles, passing and lifting, opening and shoving, shaking and tearing. They undress everything we own. There are moments when they whisper to one another, nod seriously, officially, and puff their chests out like bloated eggs. I imagine myself growing larger, my small body swelling until it fills one of those uniforms. My mother would have to pull my chin downward, instead of lifting it upward, so she can look at my face before I leave for school.

Soon, everything we own is pushed up against the wall. On one side of the room, they have stacked the heaviest and largest cans along the crusty paneling that connects the gray bricks of the wall to the gray concrete of the floor. On the other side of the room, our paintings—the imagined worlds that my parents have conjured so painstakingly onto canvas—wait lazily in a pile near the mantle, where the firelight fingers the completed strokes and daubs the colors back into a state of protean confusion.

I stand in the middle of the room and straddle the invisible Maginot Line between our paintings and our tools. The walls are hard, porous, not used to being bare. The studio looks industrial again. The splotches of paint now look misplaced on the uneven flooring, and the swaying construction light that hangs from the ceiling illuminates our home in dull waves. The room is perfectly square, small, and with their carnage the officers have made it symmetrical.

And then he turns, one of the officers. Soft brown hair pokes out from under his cap, and I am paralyzed—he is a grown-up boy. He does not look through me like the others. He looks at me. The machinery of arms continues to move around him. I look towards my father, but he does not see me. His eyes are fixed on the door, the brown rings now looking softer, sadder, as though they might melt straight out of the sockets and land in a puddle at our feet. I do not see the compassion behind the officer's gaze; I do not see his confusion at finding a young boy in the middle of his moral battlefield. I only feel naked. The sounds in the room fall away, like wooden slates, and I feel so utterly alone.

There is a crash.

Everyone stops. I have knocked over a can of blue paint. Someone has snapped a sheet over the room, I think, and lifted it, so that what was once the ceiling is no longer the ceiling and now we can see past the snow into a blackened heaven. Every man is bared to the skies. Even my father rips his gaze from the door and stares woodenly at the blue paint as it gurgles from the can like blood from a dying man. Nobody moves immediately; they all look.

And then they are upon me. I feel tears—they are mine. I remember my mother, who says that to cry is to feel, and that this is the difference between these men and those men, the men who hold the rifles and the men who cower beneath them, that these men would cry in the middle of a public square and those men were human only in their private homes, in their bedrooms in the dark of night after their children and their wives were asleep, after it did nobody any good.

My father leaps towards me. He arrives a second too late. The head officer kicks the can and the sound of the color hitting the wall reverberates with the sound of his hand hitting my face, so that the sound of flesh on flesh sings with the sound of metal ringing on concrete, and like a bell, it stings long after my father pushes him to the wall. My father still does not speak. His eyes are hard like marbles.

The officer struggles under his grasp and smiles. He feels safe, even with my father's muscular fingers sketching red outlines around his neck. He chokes out, "Keep your boy quiet, Agnitio!" I don’t know why he says that. I haven't made a sound. But then I remember the crash, and the blue paint that spilled in a steady stream. The bubbles have settled and now I see a blue so clean that I can drown in it and be free.

The officer is released, and my father's eyes wither brown like dying white roses. My mother will not come home.

They buried a rioter, they later told me, a smuggler and an insurgent. A punishment gone terribly wrong, they would say, an accident of sorts. She struggled, they’d argue, and while they had mercy she had none.

***

We knew better than to continue her work. When the pointed icicles reverted to their post-winter stubs, and the leaves began to whistle, my father drove out to the station and signed an apology on behalf of the woman who would never give them one. He hung a bell over the door. He said we would no longer live in silence. Because he signed these papers, our lives became different. Now those men would never hurt me; he painted only what they asked.

“Just follow the outlines,” he would tell me.

But under my slight hand, a bowl of fruit somehow became a bale of hay; a fish became a crocodile (and though its contours were smooth, its ridges pointed, and its yellow-green eyes hungry and inviting, we knew it would not sell—it was no fish).

After painting I would stand at the sink, washing the brushes. The water churned within the old pipes. As I waited for the paint to wash away, I crouched under the sink, with my back to the wall, so that the pipe was cradled between my knees and I could feel the delicious sloshing in my bones. A smaller universe lived inside those pipes—tiny atoms of water that had built their own nomadic neighborhood. They knew only the world of the sink, but I knew their history went much deeper than that, that they came from other droplets of water, from seas and oceans where they breathed in continents that I knew nothing about. They moved because they weren't afraid, and they liked the rush, the sudden gasp as they shimmied through the pipe, and I smiled that I could be so lucky as to feel this in my blood vessels, the incredible adventure into the unknown, the vast fields of imagination that they would transform into reality just by reaching them.

This exhilaration of shapes in the darkness, the burning rush of water—it was how it felt, I imagined, to discover something that one could forever explain but never comprehend.. I swiveled my body around and faced the wall. I pulled instinctively at the brick that was worn-down more than the others. Though it was heavy, it slid out easily at my familiar touch, and revealed a latched metal casing which I creaked open. I removed a softened book with eroded edges. It was A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, a copy that my mother had smuggled in for me from one of her trips across the border. “God forbid we let people think before they know how,” she had laughed as she gave it to me. Her laugh still echoed, somehow, dispersed permanently among the crevices of worn brick and mortar.

The bell rings. It is time for recess. A jungle of wild apes and vicious vines materialize before me, so that I cannot see more than 5 seconds ahead and 5 seconds behind. They will be around me soon—running, jumping, coming at me from all sides. In this space nobody can stop them. In this space we can play any game. We can bend time so that yesterday sticks out above tomorrow and the last hour stretches like a gauze over today and everything we feel is now and forever. We can freeze light into crystals so that the sun fractures into diamonds and traipses off blades of grass and fills the air with a green, shimmering light. We can melt the corners until they do not scrape, scorch the concrete so it does not burn, turn the windows into feathers so that when they shatter they do not scatter but they fly, far into heaven and into our pale blue sky.

But Dickie does not want to play these games. He makes the other boys stand in a square and fold their hands, the grass sinking under their weight. I don’t join them at first. But they are all looking at me. I am marooned. There is a space for me in the square, only one; there are infinite spaces for me outside the square. I run to join the game before they begin.

Dickie describes the game. He arches his back and his soft brown tufts beat like wings as he speaks.

"Most of us have played this game before," he says, though this is untrue. All of us play this game every day, but each time, this is how he begins.

"Some of you will be soldiers,” he continues, “and only one of you will carry the stones." He breaks form for a moment, bends down—he is not larger than the other boys. He gestures to Mewkes, who cradles a pile of pebbles in the bottom of his t-shirt. Mewkes steps out of his place in the square, empties the pile at Dickie's feet, and returns to his position.

"The rebel will be chosen secretly. He must place all his stones in the other boys’ pockets. If someone puts a stone in your pocket, you must put it in someone else’s. When the bell rings, the stones are counted. The one with the most stones loses. The one who loses has to collect the stones for next time.” Dickie smiles. His smile tells us that it is only a game, but it is no small thing to lose.

Red tomatoes ripen in Mewkes' cheeks and he quickly bends down to peel some dirt off of his pants. Each of us takes two steps outward, so each of us is an island, so that we can reach out our arms and legs and feel no one. We close our eyes. The wind passes through my shoelaces and traces my figure through space, pausing near my ears, molding the curves just right. I can step out of my space like a liberated paper doll. I fly above the boys. I see their paper bodies wavering in the wind, and as I move higher they look like confetti sprinkled in a square, swaying and flapping in the breeze.

I feel a warmth near my hands. I open my eyes. The boys look like sleepwalkers, shining stock-still in the noon sunlight like ornaments. Dickie stands in front of me and he spills the stones into my shirt: they are my responsibility now. I do not understand why he has chosen me. I do not want to play, but how can he know, when I stand here with my eyes closed and my feet planted in the square with roots tugging me into the ground, how can he know that I do not want to play? He nods, and I think he knows, but he lets the stones drip into my shirt until I am soaked in rock and I feel this heaviness coursing through my blood like a million little pebbles sticking to sand. Dickie looks into my eyes. He sees something there. He looks pained. But then he steps into the middle of the square, shouts, "Open them!" and a million eyes are on me, they see my face and they see the stones that are mine to give.

Fifteen minutes remain, maybe twenty. I must get rid of all my stones or I will be the rebel tomorrow, the day after, and the day after that, when really I don’t want to play, I would rather not play at all. Poor Mewkes enjoys his first day of freedom after 12 days of horror. I experience my first day of horror after 12 days of relief. I look at Mewkes and I understand. Now, I am sorry.

The boys scatter like marbles in all directions. I see Hamm tiptoeing behind a tree. He sees me and begins to run. His legs are short and he has asthma. I run after him, the stones sloshing around in my t-shirt. The elastic between us shortens, and then it snaps. I stick three stones in his pockets and run away before he can put them in mine, but not before I look into his wet eyes, see the clear tributaries of sweat that line his jawbone, the wisps of hair that congeal like blood onto his temples.

I see my action magnified all around me, into an infinite hall of mirrors, until all the boys reach into each others' pockets and enact this little drama, all with the stones I have given to them—the stones that were given to me.

On one of those days, I deposited all my belongings into my knapsack after period 5, but I did not join the square. Through the glossy windows of the bathroom, I watched the boys assemble. Their faces were muted by distance. From 15 feet above the green and several yards away, they looked like mannequins, their expressions smoothed into a non-descript blankness. Their bodies were made of plaster, dribbled from a mold and animated to grotesque perfection. As I saw my own face in the reflection, its faded outlines looming over the tiny silhouettes, a certainty shuddered through my body and paralyzed me: I will not gather stones today. The boys would not fan out like islands. Dickie would not smile knowingly at the pile of stones. The plaster would crack, beginning at the top of the skull and branching downward like a hardened river, a billion tiny earthquakes that would pry this prison to the ground, and the boys would come bursting out, with faces and bodies raw and new.

"Ars!" The deep voice careened off the bathroom walls. Mr. Harton had found me; I should have been on the green. I will not gather stones today.

"Ars!" he spoke again, louder, because I had not moved. "Ars, recess began 5 minutes ago. If you need to use the toilet, you may do so, but this is not a time for you to gawk at your classmates through a window." He chuckled. He sliced my heart with sharp clean strokes until it stood nude as an apple core. My face was wet, and I ran, bathroom door swinging behind me, my iron heels tapping out the rhythm to a haunting climax, away from the schoolhouse, past the green, through the supply room, into the bush, and out to my private patch of grass.

It was here: in this hidden capsule between a sterile schoolhouse and a sour world, I first met Bassia. My initial thought—though I could not tell you why—was of my mother.

I picked the leaves out of my hair and wiped the scratches from my forehead. I did not ask her why she was there; she did me the same courtesy.

She unwrapped a finger from around her charcoal pencil and pointed me to a neighboring patch of grass. Splashes of green paint floated in her eyes, each cradled in dark bowls above her cheeks. I stared at her, but I did not move. My legs buzzed from the sprint and electricity rushed to my feet.

She shrugged and concentrated again on her sketchbook. “Fine, stand if you like,” she said.

Her eyelashes dipped into the bowls, and then retreated, like two soft paintbrushes chiming green in unison.

"Anyway, I'm glad you're not out there today," she offered. I heard the shifting of metal spirals, and then she was holding her sketchbook under my face. "Look. I’ve drawn them."

On the page were fourteen faceless mannequins, some swelling and others shriveled and wrinkling. They breathed flames from their mouths, soared through the air, pounced onto flattened bodies, turned into stones with faces, into walls and spaces. They were everywhere, in every brick of the school building. Their bodies lined the fences of the schoolyard. The bold audacity of her lines reminded me of speckles of purple, smudges of blue.

I said, "You'll get in trouble for this."

"I've drawn a face like yours before," she replied, and rifled through her sketchbook.

But I could not look at faces in sketchbooks; I only looked at hers, and said, “Won’t you be punished?” But her hair did not fall on her face, did not soften her cheekbones like the other girls’; it was pulled back, like firm layers of pressed flowers.

“Nobody will see,” she answered. She was flowing cement, a moving statue. Nothing fell from her. Nothing chafed. “Plus, my dad’s an officer. Look, this is him.”

The hand that extended the notebook looked pale, mature and cold. But when I extended mine to receive it—trembling and wavering all the while—something in it felt hot, sent warm trickles down my fingers which collected in my knees, making them so weak that I had no choice but to sit in the grass beside her.

I looked at the picture in front of me. In the solemn charcoal, the father’s buttons glinted golden and his face shuddered with complacence. The outline was too dark for a face she had drawn so delicately, so that his features seemed to float about within them, sloshing and banging at the edges. I thought of my own father and his massive shoulders, and imagined him hunched into one of the corners of her page. I thought of his fraying brown jacket, pockmarked with dribbles of paint and softened by years of use.

“What is your father like?” Bassia asked.

“He’s…he is like you, I think.”

This pleased her. “One day I’ll be like your father, then,” she said.

I smiled down at her. “Can I see that sketch again? The one with the boys?”

She scurried through the pages, now quick to please me. She stopped suddenly, and squinted strangely at an image. “I knew I’d drawn a face like yours before,” she murmured.

I looked. It was the blurred image of a woman, drawn in sharp charcoal and rubbed nearly into oblivion. She appeared on the page like a shimmering ghost, painted in cotton and sprinkled in flour, and she hovered above the surface as though the drawing could not reach her, as though the outline could not hold her.

***

I no longer fit in the space beneath the sink. I might fit one leg in there—rarely two—and sometimes an arm, but never my head. I now had to crawl towards it, on my hands and feet like an animal, crane my neck around the ill-shapen metal, and reach blindly to pull out the brick and loosen the latch that would unlock the safe that still held A Brief History of Time.

I had grafted a new cover onto my book, upon the suggestion of my father, so that I could read the universe in daylight. We undressed his copy of Charles Dickens' Bleak House--the thicknesses of these volumes were comparable—and used this false shell to encase my book.

"Would Hawking rather watch it burn?" he asked, noticing the horror etched along my jaw.

He would not; we both knew that was the answer, that it was always the answer. I understand now the pain that this caused him, how he must have wondered if he could have encased my mother in another dressing, altering none of the text inside, and if this small concession might have kept her with us, safe behind a latch and a metal box.

This is how he lived his life, refusing even as he nodded. He grinned when the buyers came in. He asked about the minutest of details—what color should he make the popsicle in the child’s hand? What kind of wallpaper should he use in the backdrop? Should the dog stand on the left or the right? He acted as though each matter were a grave one, and noted down the customers' responses in a flurry of feigned triumph, sometimes even adding, "It's a good thing you were here! I might have painted the flowers on the wrong side of the fence!" As though he could not choose.

He spent hours applying strokes only to obscure them entirely, painting what his customers had bought on top of what he had imagined, knowing that what was beneath was for us and what was above was for sale. I marveled that this was enough; I didn’t understand. But I would come to learn that the true world was the one that they buried in the earth, the one that lived and walked and breathed in the minds of the those artists, scientists, and mathematicians who pulsated with vitality nearer to the molten core of our planet. The world that walked around us was one of the living dead, one sustained by the incredible, consistent expenditure of energy that it requires to keep a waking eye shut. My father knew that when those paintings would hang on their walls—so perfectly as described, so precisely as requested—his patrons really hung blood on their mantles, and behind the smiling faces was a staggering human sacrifice that they would never see.

***

“Gravity calls us inward,” I began as I gained the podium after a long fit of applause, gripping the glass statuette of an engraved flask, “And from here we move onward and outward.” Teachers, parents, and those that were students like me—they looked up at me, their expectant faces lining the graduation hall in rows—like dozens of painted eggs, nestled peacefully in their adjacent spaces. “My time here has been invaluable. And the support that all of you have given me—that, too, has been invaluable.”

The audience applauded and I felt dirty, as though something—the discarded voicebox of a mechanical doll—had crawled up inside of me, lodged in my throat and spoken its piece. They had expected wisdom; but I was a fraud. Out of the corner of my eye I watched an old gentleman smooth his white hair behind his ears, straighten his tie, stiffen his spine into his seat to sit up just a little bit taller. Hair, tie, spine…Those gestures reeled in my mind, even as I continued my speech. It was guilt—I knew this then, and I know it now—because he sat up just a little bit straighter to hear me, because this man in his spruced suit and his wrinkled skin, this man with thousands of years of experience above my own, perked up his ears to listen to something he thought I had to say.

I stepped down and took my seat at the front of the class. The podium loomed above me. No wonder they believed me, I thought, no wonder they approved. Crystals of perspiration leaked outward like veins where I gripped my award, smudging the clear glass so I could no longer see through it. There was an ugliness to my success, a supreme embarrassment, and I hated for them to look at me this way, with such genuine respect. I told myself that I needed the money, for the real research that I would one day do. In the meantime I could give them what they wanted—discoveries of things that they already believed to be true.

"Doesn't the hall look beautiful tonight?" A woman walked up to me from behind, her white cotton dress swishing above the floor as its tip grazed my ankle. The awards ceremony had ended; now we all stood together in the reception hall.

"Yes. It's very nice." I tried to smile, but I imagined noxious vapors emanating from the cherrywood walls, fumes exhaled from the light pink flowers that lined the paneling.

"I helped to decorate, you know." She moved closer to me. Last night, Bassia had grabbed my hands and twirled me around the grass, so that both of our feet were soaked from the inside out and I tracked wet footprints all the way to my bed.

“That was kind of you," I responded. I wished that she would leave. The cotton looked soft, comfortable.

"I loved your speech."

I couldn't stand to look at that white dress any longer. "Thank you, I appreciate that," I said, as I pressed her hands in gratitude. "I'm so sorry, but I think my father is waiting for me, actually. Your decorations are lovely."

My mother had always told me that the furniture could breathe, that everything breathed, and was only as alive as the goodness poured into it. She told me that this was why, in imperialist countries, the incidence of depression was so high. The objects bought with exploited money would breathe the guilt back onto their owners, perpetuating selfishness not onto the perpetrators, but instead forwards, onto new palettes, untouched psyches.

In my pocket I fingered the real acceptance speech, the one I had spoken in my head as I read my lies out loud:

“My mother believed in a beautiful order,” I had wished to say. “She cherished uncertainties: the uncertainty of whether we are, in fact, alone, the uncertainty with which the ant conceives of the man and the man conceives of the God, the uncertainty that I stand before you today. It is my duty to preserve these uncertainties. I believe in the power of the unknowable, of convictions that dissolve in the air like magic, of rocks that fall from the sky, of the profound beauty that exists in the piece of ice that stands in the middle of a steaming desert. I fear the abolition of imagination. I fear the meager belief, the paltry certainty—amid a cloud of qualification, skeptification, mediation—the certainty that the object which you hold in your bleeding hands, the hand of your dying father, the stone that cradles your mother’s head, the stones you place in another man’s pocket, that perhaps these are real. I fear the present moment, constantly replaced, never remembered…does not exist.”

This was the speech that Bassia had applauded the night before, her claps shattering into a million invisible footsteps that filled the air with a dusty moonlight. We had met in the park; I never went to her father’s house, and she rarely came to the studio. When I joined her on our bench, she didn’t speak, not a word, but gripped my fingertips with a delicate reverence. At that moment, I knew: she would not come to my graduation. She would never hear the other speech, the one that could never be acceptable in the night-time silence of ourselves, the one I could make in front of everybody except her.

In the end she would not disobey her father; I had been right from the start. He and my own father were enemies, each of equal stature, though her father lived in a tower and my father crept beneath it—and I could almost hear my mother whispering in his ear, an exhortation barely intelligible, “…the palace gardener carries a legacy of roses, though they will never bear his name…” Bassia was like my father—her true painting happened underneath, her innovations were hidden, her revolution was a private one that lived and died in the beating of her own heart.

***

I knew I would not see her in the summer following our graduation. She worked with her father now, naming files and mailing orders. I imagined her in a dusky room layered in shades of gray, encircled by metal cabinets and rooted silver chairs. As the buyers rushed to the studio to collect their paintings, and as my father smiled and smoothed the plastic cases, I thought only of Bassia’s graying face cowering like a lamp in the shadows.

Only once, during the final weeks of summer, did she come to see me. She hadn’t decayed to shadows, as I had guessed, but was instead suffused with color—cheeks pink, eyes green, face laced with light twinkles of sweat. For a second I remembered, tried hopefully to imagine this girl waiting in the schoolyard privacy of a patch of grass, but somewhere in her muted smile I could only hear her boots, clicking on the tar-lined roads.

"I can’t stay long,” she said. “But I want you to know something. You have to look at this." She held up a ragged sketchbook. The drawings were smudged with her lead fingerprints, outlined and erased and shaded again in a younger hand that was far less delicate than the one that held the sketchbook open now. "Do you know who that is?"

On that day long ago, I had not really seen it; I had looked but perceived a ghost. And I would never understand why Bassia chose this day, this moment, to make me bear witness—a second time—to this apparition. But as I gazed at the sketch now, the figure’s blurry countenance became clearer by discrete shades. It was a stranger's face, a woman's, and then a figure from my past…

“I used to go through my father’s folders,” Bassia’s voice came to me in thin strings of air, penetrating the thickness which slowly suffocated me, “because there was…I don’t know, there was something in those faces. I—I didn’t draw all of them.”

She flipped the pages to sketches of other prisoners. She sifted through a graveyard of spirits. They all had a quality similar to my mother’s—that odd look of surprise at being photographed at that particular moment above all others, an inborn fear of being seen, a hidden challenge to the lens.

"You don't know my mother," I responded. I wasn't angry; it was simply a fact.

"No, I don't," she agreed. "I only read a folder with her name on the cover.” She held it out to me. The edges were soft, bent—it had been read, opened and closed and opened again. But I would not dare to touch it.

Bassia placed it on the table, as though it were fragile as glass, as though even now there was something left to break.

“I thought about her for so many years,” Bassia whispered. “She said something to those officers that I always remember: ‘The truth is in the earth. This is where we find it, this is where we bury it. Things we put in the ground, they don't die—‘”

“They grow,” I finished.

***

The final hum of the buyers' rush fades into the concrete pores, and again the studio is bare. Throughout the autumn months, the color had washed away in gentle waves, and now only a few paintings remain scattered on the freshly-scrubbed wooden floor. Tools have been put away, the inventory lists have been filed and buried in the safe behind the shed, and the studio doors have closed for the year. Dying leaves and the first buds of snow rap silently at the windows, accompanied steadily by the clock's tired heartbeat.

My father, too, breathes more easily in this quiet. Still we remember the blue that streaked the floor, the echoing clouds of the clanging of flesh, and the soft exchange of our lives for hers. But I do not see blood in this blue paint—I see stars, threads looped infinitely upon themselves, smudged fingers and red-hot fire. My father dots the soldier's head with blue. Inside his canvas they trudge in the dirt, their smocks of manhood tarnished with red. They step over faceless bodies and hunched rifles. They all look the same—stripped of their limbs and their posture, enemies and countrymen writhe in neighboring hovels of dirt. The colors are toned to black, dulled, except for the red that seeps out from everywhere. They are no longer men, except for the red.

The door swings open. The air clenches. The painted soldiers pause mid-death. Bassia stands in the doorframe. She looks perfectly symmetrical, outlined in hard trembling strokes and colored with soft sponges. Her eyes scream sympathy; her hands feign peace.

For a moment nobody moves. We all look at each other.

"They found one of your notebooks.” She speaks in a voice carried by no breath at all. “The police are looking for you. Ars!" She speaks my name and then she hears it. "Ars." I imagine her trapped inside a tear, undulating with its music, the colors of her face whirling into a primal muddle.

She looks at me through this glassy sheet, and maybe she imagines my face as it will look in her sketchbook. It is already over, I am a charcoal representation of bones and flesh, a vaguely outlined remnant of an electrical being.

"My father just phoned the station," she continued, her voice rising. "They're coming now." We don’t move. "I can't run much faster than they can,”—she is shouting now, she has walked up and clutches my arm—“They should be here by now."

But my father is already standing next to me with my books piled neatly in his arms. His bulky hand trembles, very slightly, as he holds my knapsack out for me. Even now, he says nothing, but touches my arm and offers me help. I feel my heart in my throat; I cannot look at him.

I hold Bassia's shoulders and I look at her. I do not kiss her because I must look at her. She whispers something about my mother, about stones and boxes. Then, I run.

The familiar sun, at last, burns orange and the universe is in a state of alarm. Leaves crunch on the ground but do not fall from the sky. The trees are bare, bowing downwards to look at their banished leaves. Like rows of mourners, the trunks hold their vigils on either side of the street, standing still and silent as my feet send puddles of leaves upwards into whirlpools.

Finally her marble headstone gleams orange in the dusk. First it is one in an orchard of glimmering fruits, and then it is the only one, and I am touching it, its solid weight holding up my head because my neck cannot.

Cold tears fall on my cheeks but I do not cry. They come from the sky, falling in eerie vortexes and settling into the grass like dandelion ashes. They are solid but they touch me, and they melt. I do not shiver because I cannot move.

For a time, I wait, and then I begin to dig. I fall on my knees and pull the grass away at its roots, deeper and deeper, until my hands are raw and a hole materializes. I settle my knapsack into this tomb, smooth the clasp over the opening, and it disappears in the dirt which disappears in the snow.

But I am not finished; now I begin to dig again, a hole right beside the one I have just filled up. Beneath the snow I feel the blades of grass, and I remember that Bassia had clapped and that blades of grass had shivered in her soft echo, that it had been so quiet and so silent and so still, and that she had clasped my fingertips and had not said a word. "I'm scared," I had said, "I'll be killed." And nothing in her faltered, nothing grieved. As if she had always thought so; as if this was why she loved me.

I continue to dig, now beneath the grass I find the dirt, and inside the cold my fingertips feel warm.

"Aren't you afraid?" I had asked her, "what if they punish you too?" And she had laughed, had thrown back her head and laughed until the trees shuddered in distress. "They'll never punish me," she had answered—“ because your father is an officer?”—but she only laughed again. "They'll never punish me," and she stroked my face, tracing my chin with the tips of her hands, "because I'm nothing like you."

My mother's gravestone looms above me, silent and gray, while my hands freeze, my knees ache, my fingers burn with the heat of the dead...

"We can't all be like you, Ars."

I keep moving, deeper and deeper, until my forefinger bends on something hard. Faster now—faster—and deeper—and soon it is out, and open, the lid of the metal box flapping angrily in the rising winds.

"We can't all make the sacrifice or there would be nothing left to give. You'll be there one day, Ars, you will live in a different world...but your father never will." The tears had carved stone rivulets down my face, and she had pulled me up, held me so I stood, the summer evaporating around us and undulating its particles in the darkness. "To you he is your father, but to them he is no hero; they won’t harm him. Because they can use him." And then I had fallen, trembling, to my knees, but Bassia spoke louder, "because you may not see what he's made of, but they do.”

I open the box, my fingers red from snow, and I lift the candle from inside its container. The wax is pale, uneven, plastered with Bassia’s invisible fingerprints, carved in her design.

"But they will know that you are not like him. When that time comes, I will tell you where to go. I have buried it already.”

Beneath the candle there is a file. And in the file is an identification card with the photo of a stranger, and the name of a stranger—of a boy who looks almost like me, my age, same build, same hair, but lacking something in the eyes. Beneath the card there are papers that make me legal and make me somebody else, and with them she has clipped a release form, signed with the official hand and sanctioned by the official stamp, that I will show to the border patrol, that they will keep and file away for long after I am gone.

***

The studio is empty. There is no whirring of a breath and no tick of a heartbeat. The painted soldiers march and crawl, march and crawl until there is nothing left. Their tiny blue hats are strewn about their limbs and these tributaries of blood meander downward until they form a single stream, a unified trunk and a dark-red palimpsest of a barren wasteland. The end, the end, the end. But it does not stop, because the ends flow in rivers and the deaths do not stop but begin to move. They march through fields where nothing grows, gush into the foreground, cascading red with every breath…but there, in the bottom right-hand corner, in a pool of blood that threatens to spill out from the painting onto the concrete floor—there, floating above his secret strokes, outlined in a splash of crimson paint, is the faintest skeleton of a red, red rose.

There, in that moment, it became irreversible: this snow would not last forever. The world could not sustain it. And though it all seemed solid—the branches, our faces, and even the sky—I felt the shudder of this notion pass through me, with determined certainty, until it owned me.

My father’s moans exploded in distinct bursts. As his sobs shook the flakes around his shoulders, he seemed to shimmer in a white haze, as if reality itself had relented around his figure and created a cushion—as though the world were sorry that my mother lay beneath the ground as he stood above it. I wonder now how she would have painted the scene: he behind me, with his heavy hands on my shoulders, and then my small silhouette, shadowed inside his, and then herself—extending from our feet in a rectangular plot, lost somewhere beneath the snow and the fresh brown stubble. She would not paint the dirt, I thought, not the coffin but her dress, white, and cotton, and she would not paint the wooden clasp but instead her hands, neat and folded, poised for an endless formality—her fingers no longer speckled in purple, her palms no longer dashed in blue.

(They will put the stone here—he had said—and don’t stand here—she is sleeping—and soon the grass will grow, on this mound of dirt—and then we’ll know her from the stone. Soon the grass will grow, soon, and then it won’t look so new but how do I know it will always feel like this?)

Or perhaps she would have painted something else entirely—herself standing next to us, and they beneath the ground instead of her. She would paint exactly what they didn’t want her to paint: something unreal and yet entirely possible. And then they would put her in the ground, and still, she would paint exactly this.

It was that they had been after, that glimmer of self-assertion that beat in her blood and burst from her hands like magic. To them, she was not the color of flowers in the moonlight and the fresh scent of birdseed at the door, the sparkling red of a ripe tomato, the cooling sweep of a wedding band as they closed their eyes for bed…she was not a voice that rode on waves, rising and falling before pausing, painting and eating before sleeping. No, they buried a body of something else, of accusations they littered against her name: 42 censored pamphlets, 18 smuggled paintings, 14 demonstrations, hundreds of exhortations for revolution, thousands of wails for a return of color.

(She would have smirked, I thought, as she finally understood: she might rest, but now they never would.)

I shivered as a gust of wind blew at my side, striking me from the space where she might have been standing. At my feet, the mound of dirt was slowly covered with white. I imagined the snow seeping through the cracks in her coffin, trickling onto her face, smoothing her wrinkles away until she was the young woman I had never known.

I slept in my father's bed that night, and marveled that he breathed, and that he continued to breathe all through the night.

***

I open the door that connects our bedroom to the studio. My mother’s brushes still stare back at me, stuffed haphazardly into an empty paint can and fanned out against the window. As the sun rises, they look like a medley of tousled heads, gleaming colors that fray the edges of the nighttime until it becomes the iridescent day. And I think, maybe today my mother will come home…

And then there she is, knocking at our door! I rush to open it. But it is only the uniformed officers; they have come instead, with their pressed blue suits and their ironed hats.

Soon, my father too is awake, and they are around us. They shuffle through our studio, upturning boxes and spilling tools onto the floor. When they squat and sift through the roughage, they look like boys in creased trousers, digging for marbles in the sand; when they stand and arch their backs, surveying their progress, they look like men. They work as a flawless unit. Even in the near-darkness of the studio, they move in perfectly choreographed cycles, dragging their shadows behind them like feathers—or capes, that flutter behind them, waving and dancing in the firelight.

My father looks like a mouse trapped in an array of circling metal gears. His wide shoulders are hunched into his jacket, and his fists are plunged deep into his pockets. He stands completely still, save for the occasional glance at me, and the consistent gaze at the door. I don't know if he sees either of these things. His eyes look dead, glassy. They contain nothing of the soft brown rings that remind me of planets and love.

He coughs.

The officers all look up for a moment, pause like dangling puppets, but in an instant they animate again. They return to their cycles, passing and lifting, opening and shoving, shaking and tearing. They undress everything we own. There are moments when they whisper to one another, nod seriously, officially, and puff their chests out like bloated eggs. I imagine myself growing larger, my small body swelling until it fills one of those uniforms. My mother would have to pull my chin downward, instead of lifting it upward, so she can look at my face before I leave for school.

Soon, everything we own is pushed up against the wall. On one side of the room, they have stacked the heaviest and largest cans along the crusty paneling that connects the gray bricks of the wall to the gray concrete of the floor. On the other side of the room, our paintings—the imagined worlds that my parents have conjured so painstakingly onto canvas—wait lazily in a pile near the mantle, where the firelight fingers the completed strokes and daubs the colors back into a state of protean confusion.

I stand in the middle of the room and straddle the invisible Maginot Line between our paintings and our tools. The walls are hard, porous, not used to being bare. The studio looks industrial again. The splotches of paint now look misplaced on the uneven flooring, and the swaying construction light that hangs from the ceiling illuminates our home in dull waves. The room is perfectly square, small, and with their carnage the officers have made it symmetrical.

And then he turns, one of the officers. Soft brown hair pokes out from under his cap, and I am paralyzed—he is a grown-up boy. He does not look through me like the others. He looks at me. The machinery of arms continues to move around him. I look towards my father, but he does not see me. His eyes are fixed on the door, the brown rings now looking softer, sadder, as though they might melt straight out of the sockets and land in a puddle at our feet. I do not see the compassion behind the officer's gaze; I do not see his confusion at finding a young boy in the middle of his moral battlefield. I only feel naked. The sounds in the room fall away, like wooden slates, and I feel so utterly alone.

There is a crash.

Everyone stops. I have knocked over a can of blue paint. Someone has snapped a sheet over the room, I think, and lifted it, so that what was once the ceiling is no longer the ceiling and now we can see past the snow into a blackened heaven. Every man is bared to the skies. Even my father rips his gaze from the door and stares woodenly at the blue paint as it gurgles from the can like blood from a dying man. Nobody moves immediately; they all look.

And then they are upon me. I feel tears—they are mine. I remember my mother, who says that to cry is to feel, and that this is the difference between these men and those men, the men who hold the rifles and the men who cower beneath them, that these men would cry in the middle of a public square and those men were human only in their private homes, in their bedrooms in the dark of night after their children and their wives were asleep, after it did nobody any good.

My father leaps towards me. He arrives a second too late. The head officer kicks the can and the sound of the color hitting the wall reverberates with the sound of his hand hitting my face, so that the sound of flesh on flesh sings with the sound of metal ringing on concrete, and like a bell, it stings long after my father pushes him to the wall. My father still does not speak. His eyes are hard like marbles.

The officer struggles under his grasp and smiles. He feels safe, even with my father's muscular fingers sketching red outlines around his neck. He chokes out, "Keep your boy quiet, Agnitio!" I don’t know why he says that. I haven't made a sound. But then I remember the crash, and the blue paint that spilled in a steady stream. The bubbles have settled and now I see a blue so clean that I can drown in it and be free.

The officer is released, and my father's eyes wither brown like dying white roses. My mother will not come home.

They buried a rioter, they later told me, a smuggler and an insurgent. A punishment gone terribly wrong, they would say, an accident of sorts. She struggled, they’d argue, and while they had mercy she had none.

***

We knew better than to continue her work. When the pointed icicles reverted to their post-winter stubs, and the leaves began to whistle, my father drove out to the station and signed an apology on behalf of the woman who would never give them one. He hung a bell over the door. He said we would no longer live in silence. Because he signed these papers, our lives became different. Now those men would never hurt me; he painted only what they asked.

“Just follow the outlines,” he would tell me.

But under my slight hand, a bowl of fruit somehow became a bale of hay; a fish became a crocodile (and though its contours were smooth, its ridges pointed, and its yellow-green eyes hungry and inviting, we knew it would not sell—it was no fish).

After painting I would stand at the sink, washing the brushes. The water churned within the old pipes. As I waited for the paint to wash away, I crouched under the sink, with my back to the wall, so that the pipe was cradled between my knees and I could feel the delicious sloshing in my bones. A smaller universe lived inside those pipes—tiny atoms of water that had built their own nomadic neighborhood. They knew only the world of the sink, but I knew their history went much deeper than that, that they came from other droplets of water, from seas and oceans where they breathed in continents that I knew nothing about. They moved because they weren't afraid, and they liked the rush, the sudden gasp as they shimmied through the pipe, and I smiled that I could be so lucky as to feel this in my blood vessels, the incredible adventure into the unknown, the vast fields of imagination that they would transform into reality just by reaching them.

This exhilaration of shapes in the darkness, the burning rush of water—it was how it felt, I imagined, to discover something that one could forever explain but never comprehend.. I swiveled my body around and faced the wall. I pulled instinctively at the brick that was worn-down more than the others. Though it was heavy, it slid out easily at my familiar touch, and revealed a latched metal casing which I creaked open. I removed a softened book with eroded edges. It was A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, a copy that my mother had smuggled in for me from one of her trips across the border. “God forbid we let people think before they know how,” she had laughed as she gave it to me. Her laugh still echoed, somehow, dispersed permanently among the crevices of worn brick and mortar.

The bell rings. It is time for recess. A jungle of wild apes and vicious vines materialize before me, so that I cannot see more than 5 seconds ahead and 5 seconds behind. They will be around me soon—running, jumping, coming at me from all sides. In this space nobody can stop them. In this space we can play any game. We can bend time so that yesterday sticks out above tomorrow and the last hour stretches like a gauze over today and everything we feel is now and forever. We can freeze light into crystals so that the sun fractures into diamonds and traipses off blades of grass and fills the air with a green, shimmering light. We can melt the corners until they do not scrape, scorch the concrete so it does not burn, turn the windows into feathers so that when they shatter they do not scatter but they fly, far into heaven and into our pale blue sky.

But Dickie does not want to play these games. He makes the other boys stand in a square and fold their hands, the grass sinking under their weight. I don’t join them at first. But they are all looking at me. I am marooned. There is a space for me in the square, only one; there are infinite spaces for me outside the square. I run to join the game before they begin.

Dickie describes the game. He arches his back and his soft brown tufts beat like wings as he speaks.

"Most of us have played this game before," he says, though this is untrue. All of us play this game every day, but each time, this is how he begins.

"Some of you will be soldiers,” he continues, “and only one of you will carry the stones." He breaks form for a moment, bends down—he is not larger than the other boys. He gestures to Mewkes, who cradles a pile of pebbles in the bottom of his t-shirt. Mewkes steps out of his place in the square, empties the pile at Dickie's feet, and returns to his position.

"The rebel will be chosen secretly. He must place all his stones in the other boys’ pockets. If someone puts a stone in your pocket, you must put it in someone else’s. When the bell rings, the stones are counted. The one with the most stones loses. The one who loses has to collect the stones for next time.” Dickie smiles. His smile tells us that it is only a game, but it is no small thing to lose.

Red tomatoes ripen in Mewkes' cheeks and he quickly bends down to peel some dirt off of his pants. Each of us takes two steps outward, so each of us is an island, so that we can reach out our arms and legs and feel no one. We close our eyes. The wind passes through my shoelaces and traces my figure through space, pausing near my ears, molding the curves just right. I can step out of my space like a liberated paper doll. I fly above the boys. I see their paper bodies wavering in the wind, and as I move higher they look like confetti sprinkled in a square, swaying and flapping in the breeze.

I feel a warmth near my hands. I open my eyes. The boys look like sleepwalkers, shining stock-still in the noon sunlight like ornaments. Dickie stands in front of me and he spills the stones into my shirt: they are my responsibility now. I do not understand why he has chosen me. I do not want to play, but how can he know, when I stand here with my eyes closed and my feet planted in the square with roots tugging me into the ground, how can he know that I do not want to play? He nods, and I think he knows, but he lets the stones drip into my shirt until I am soaked in rock and I feel this heaviness coursing through my blood like a million little pebbles sticking to sand. Dickie looks into my eyes. He sees something there. He looks pained. But then he steps into the middle of the square, shouts, "Open them!" and a million eyes are on me, they see my face and they see the stones that are mine to give.

Fifteen minutes remain, maybe twenty. I must get rid of all my stones or I will be the rebel tomorrow, the day after, and the day after that, when really I don’t want to play, I would rather not play at all. Poor Mewkes enjoys his first day of freedom after 12 days of horror. I experience my first day of horror after 12 days of relief. I look at Mewkes and I understand. Now, I am sorry.

The boys scatter like marbles in all directions. I see Hamm tiptoeing behind a tree. He sees me and begins to run. His legs are short and he has asthma. I run after him, the stones sloshing around in my t-shirt. The elastic between us shortens, and then it snaps. I stick three stones in his pockets and run away before he can put them in mine, but not before I look into his wet eyes, see the clear tributaries of sweat that line his jawbone, the wisps of hair that congeal like blood onto his temples.

I see my action magnified all around me, into an infinite hall of mirrors, until all the boys reach into each others' pockets and enact this little drama, all with the stones I have given to them—the stones that were given to me.

On one of those days, I deposited all my belongings into my knapsack after period 5, but I did not join the square. Through the glossy windows of the bathroom, I watched the boys assemble. Their faces were muted by distance. From 15 feet above the green and several yards away, they looked like mannequins, their expressions smoothed into a non-descript blankness. Their bodies were made of plaster, dribbled from a mold and animated to grotesque perfection. As I saw my own face in the reflection, its faded outlines looming over the tiny silhouettes, a certainty shuddered through my body and paralyzed me: I will not gather stones today. The boys would not fan out like islands. Dickie would not smile knowingly at the pile of stones. The plaster would crack, beginning at the top of the skull and branching downward like a hardened river, a billion tiny earthquakes that would pry this prison to the ground, and the boys would come bursting out, with faces and bodies raw and new.

"Ars!" The deep voice careened off the bathroom walls. Mr. Harton had found me; I should have been on the green. I will not gather stones today.

"Ars!" he spoke again, louder, because I had not moved. "Ars, recess began 5 minutes ago. If you need to use the toilet, you may do so, but this is not a time for you to gawk at your classmates through a window." He chuckled. He sliced my heart with sharp clean strokes until it stood nude as an apple core. My face was wet, and I ran, bathroom door swinging behind me, my iron heels tapping out the rhythm to a haunting climax, away from the schoolhouse, past the green, through the supply room, into the bush, and out to my private patch of grass.

It was here: in this hidden capsule between a sterile schoolhouse and a sour world, I first met Bassia. My initial thought—though I could not tell you why—was of my mother.

I picked the leaves out of my hair and wiped the scratches from my forehead. I did not ask her why she was there; she did me the same courtesy.

She unwrapped a finger from around her charcoal pencil and pointed me to a neighboring patch of grass. Splashes of green paint floated in her eyes, each cradled in dark bowls above her cheeks. I stared at her, but I did not move. My legs buzzed from the sprint and electricity rushed to my feet.

She shrugged and concentrated again on her sketchbook. “Fine, stand if you like,” she said.

Her eyelashes dipped into the bowls, and then retreated, like two soft paintbrushes chiming green in unison.

"Anyway, I'm glad you're not out there today," she offered. I heard the shifting of metal spirals, and then she was holding her sketchbook under my face. "Look. I’ve drawn them."

On the page were fourteen faceless mannequins, some swelling and others shriveled and wrinkling. They breathed flames from their mouths, soared through the air, pounced onto flattened bodies, turned into stones with faces, into walls and spaces. They were everywhere, in every brick of the school building. Their bodies lined the fences of the schoolyard. The bold audacity of her lines reminded me of speckles of purple, smudges of blue.

I said, "You'll get in trouble for this."

"I've drawn a face like yours before," she replied, and rifled through her sketchbook.

But I could not look at faces in sketchbooks; I only looked at hers, and said, “Won’t you be punished?” But her hair did not fall on her face, did not soften her cheekbones like the other girls’; it was pulled back, like firm layers of pressed flowers.

“Nobody will see,” she answered. She was flowing cement, a moving statue. Nothing fell from her. Nothing chafed. “Plus, my dad’s an officer. Look, this is him.”

The hand that extended the notebook looked pale, mature and cold. But when I extended mine to receive it—trembling and wavering all the while—something in it felt hot, sent warm trickles down my fingers which collected in my knees, making them so weak that I had no choice but to sit in the grass beside her.

I looked at the picture in front of me. In the solemn charcoal, the father’s buttons glinted golden and his face shuddered with complacence. The outline was too dark for a face she had drawn so delicately, so that his features seemed to float about within them, sloshing and banging at the edges. I thought of my own father and his massive shoulders, and imagined him hunched into one of the corners of her page. I thought of his fraying brown jacket, pockmarked with dribbles of paint and softened by years of use.

“What is your father like?” Bassia asked.

“He’s…he is like you, I think.”

This pleased her. “One day I’ll be like your father, then,” she said.

I smiled down at her. “Can I see that sketch again? The one with the boys?”

She scurried through the pages, now quick to please me. She stopped suddenly, and squinted strangely at an image. “I knew I’d drawn a face like yours before,” she murmured.

I looked. It was the blurred image of a woman, drawn in sharp charcoal and rubbed nearly into oblivion. She appeared on the page like a shimmering ghost, painted in cotton and sprinkled in flour, and she hovered above the surface as though the drawing could not reach her, as though the outline could not hold her.

***

I no longer fit in the space beneath the sink. I might fit one leg in there—rarely two—and sometimes an arm, but never my head. I now had to crawl towards it, on my hands and feet like an animal, crane my neck around the ill-shapen metal, and reach blindly to pull out the brick and loosen the latch that would unlock the safe that still held A Brief History of Time.

I had grafted a new cover onto my book, upon the suggestion of my father, so that I could read the universe in daylight. We undressed his copy of Charles Dickens' Bleak House--the thicknesses of these volumes were comparable—and used this false shell to encase my book.

"Would Hawking rather watch it burn?" he asked, noticing the horror etched along my jaw.

He would not; we both knew that was the answer, that it was always the answer. I understand now the pain that this caused him, how he must have wondered if he could have encased my mother in another dressing, altering none of the text inside, and if this small concession might have kept her with us, safe behind a latch and a metal box.

This is how he lived his life, refusing even as he nodded. He grinned when the buyers came in. He asked about the minutest of details—what color should he make the popsicle in the child’s hand? What kind of wallpaper should he use in the backdrop? Should the dog stand on the left or the right? He acted as though each matter were a grave one, and noted down the customers' responses in a flurry of feigned triumph, sometimes even adding, "It's a good thing you were here! I might have painted the flowers on the wrong side of the fence!" As though he could not choose.

He spent hours applying strokes only to obscure them entirely, painting what his customers had bought on top of what he had imagined, knowing that what was beneath was for us and what was above was for sale. I marveled that this was enough; I didn’t understand. But I would come to learn that the true world was the one that they buried in the earth, the one that lived and walked and breathed in the minds of the those artists, scientists, and mathematicians who pulsated with vitality nearer to the molten core of our planet. The world that walked around us was one of the living dead, one sustained by the incredible, consistent expenditure of energy that it requires to keep a waking eye shut. My father knew that when those paintings would hang on their walls—so perfectly as described, so precisely as requested—his patrons really hung blood on their mantles, and behind the smiling faces was a staggering human sacrifice that they would never see.

***

“Gravity calls us inward,” I began as I gained the podium after a long fit of applause, gripping the glass statuette of an engraved flask, “And from here we move onward and outward.” Teachers, parents, and those that were students like me—they looked up at me, their expectant faces lining the graduation hall in rows—like dozens of painted eggs, nestled peacefully in their adjacent spaces. “My time here has been invaluable. And the support that all of you have given me—that, too, has been invaluable.”

The audience applauded and I felt dirty, as though something—the discarded voicebox of a mechanical doll—had crawled up inside of me, lodged in my throat and spoken its piece. They had expected wisdom; but I was a fraud. Out of the corner of my eye I watched an old gentleman smooth his white hair behind his ears, straighten his tie, stiffen his spine into his seat to sit up just a little bit taller. Hair, tie, spine…Those gestures reeled in my mind, even as I continued my speech. It was guilt—I knew this then, and I know it now—because he sat up just a little bit straighter to hear me, because this man in his spruced suit and his wrinkled skin, this man with thousands of years of experience above my own, perked up his ears to listen to something he thought I had to say.

I stepped down and took my seat at the front of the class. The podium loomed above me. No wonder they believed me, I thought, no wonder they approved. Crystals of perspiration leaked outward like veins where I gripped my award, smudging the clear glass so I could no longer see through it. There was an ugliness to my success, a supreme embarrassment, and I hated for them to look at me this way, with such genuine respect. I told myself that I needed the money, for the real research that I would one day do. In the meantime I could give them what they wanted—discoveries of things that they already believed to be true.

"Doesn't the hall look beautiful tonight?" A woman walked up to me from behind, her white cotton dress swishing above the floor as its tip grazed my ankle. The awards ceremony had ended; now we all stood together in the reception hall.

"Yes. It's very nice." I tried to smile, but I imagined noxious vapors emanating from the cherrywood walls, fumes exhaled from the light pink flowers that lined the paneling.

"I helped to decorate, you know." She moved closer to me. Last night, Bassia had grabbed my hands and twirled me around the grass, so that both of our feet were soaked from the inside out and I tracked wet footprints all the way to my bed.

“That was kind of you," I responded. I wished that she would leave. The cotton looked soft, comfortable.

"I loved your speech."

I couldn't stand to look at that white dress any longer. "Thank you, I appreciate that," I said, as I pressed her hands in gratitude. "I'm so sorry, but I think my father is waiting for me, actually. Your decorations are lovely."

My mother had always told me that the furniture could breathe, that everything breathed, and was only as alive as the goodness poured into it. She told me that this was why, in imperialist countries, the incidence of depression was so high. The objects bought with exploited money would breathe the guilt back onto their owners, perpetuating selfishness not onto the perpetrators, but instead forwards, onto new palettes, untouched psyches.

In my pocket I fingered the real acceptance speech, the one I had spoken in my head as I read my lies out loud:

“My mother believed in a beautiful order,” I had wished to say. “She cherished uncertainties: the uncertainty of whether we are, in fact, alone, the uncertainty with which the ant conceives of the man and the man conceives of the God, the uncertainty that I stand before you today. It is my duty to preserve these uncertainties. I believe in the power of the unknowable, of convictions that dissolve in the air like magic, of rocks that fall from the sky, of the profound beauty that exists in the piece of ice that stands in the middle of a steaming desert. I fear the abolition of imagination. I fear the meager belief, the paltry certainty—amid a cloud of qualification, skeptification, mediation—the certainty that the object which you hold in your bleeding hands, the hand of your dying father, the stone that cradles your mother’s head, the stones you place in another man’s pocket, that perhaps these are real. I fear the present moment, constantly replaced, never remembered…does not exist.”

This was the speech that Bassia had applauded the night before, her claps shattering into a million invisible footsteps that filled the air with a dusty moonlight. We had met in the park; I never went to her father’s house, and she rarely came to the studio. When I joined her on our bench, she didn’t speak, not a word, but gripped my fingertips with a delicate reverence. At that moment, I knew: she would not come to my graduation. She would never hear the other speech, the one that could never be acceptable in the night-time silence of ourselves, the one I could make in front of everybody except her.

In the end she would not disobey her father; I had been right from the start. He and my own father were enemies, each of equal stature, though her father lived in a tower and my father crept beneath it—and I could almost hear my mother whispering in his ear, an exhortation barely intelligible, “…the palace gardener carries a legacy of roses, though they will never bear his name…” Bassia was like my father—her true painting happened underneath, her innovations were hidden, her revolution was a private one that lived and died in the beating of her own heart.

***

I knew I would not see her in the summer following our graduation. She worked with her father now, naming files and mailing orders. I imagined her in a dusky room layered in shades of gray, encircled by metal cabinets and rooted silver chairs. As the buyers rushed to the studio to collect their paintings, and as my father smiled and smoothed the plastic cases, I thought only of Bassia’s graying face cowering like a lamp in the shadows.

Only once, during the final weeks of summer, did she come to see me. She hadn’t decayed to shadows, as I had guessed, but was instead suffused with color—cheeks pink, eyes green, face laced with light twinkles of sweat. For a second I remembered, tried hopefully to imagine this girl waiting in the schoolyard privacy of a patch of grass, but somewhere in her muted smile I could only hear her boots, clicking on the tar-lined roads.

"I can’t stay long,” she said. “But I want you to know something. You have to look at this." She held up a ragged sketchbook. The drawings were smudged with her lead fingerprints, outlined and erased and shaded again in a younger hand that was far less delicate than the one that held the sketchbook open now. "Do you know who that is?"

On that day long ago, I had not really seen it; I had looked but perceived a ghost. And I would never understand why Bassia chose this day, this moment, to make me bear witness—a second time—to this apparition. But as I gazed at the sketch now, the figure’s blurry countenance became clearer by discrete shades. It was a stranger's face, a woman's, and then a figure from my past…

“I used to go through my father’s folders,” Bassia’s voice came to me in thin strings of air, penetrating the thickness which slowly suffocated me, “because there was…I don’t know, there was something in those faces. I—I didn’t draw all of them.”

She flipped the pages to sketches of other prisoners. She sifted through a graveyard of spirits. They all had a quality similar to my mother’s—that odd look of surprise at being photographed at that particular moment above all others, an inborn fear of being seen, a hidden challenge to the lens.

"You don't know my mother," I responded. I wasn't angry; it was simply a fact.

"No, I don't," she agreed. "I only read a folder with her name on the cover.” She held it out to me. The edges were soft, bent—it had been read, opened and closed and opened again. But I would not dare to touch it.

Bassia placed it on the table, as though it were fragile as glass, as though even now there was something left to break.

“I thought about her for so many years,” Bassia whispered. “She said something to those officers that I always remember: ‘The truth is in the earth. This is where we find it, this is where we bury it. Things we put in the ground, they don't die—‘”

“They grow,” I finished.

***

The final hum of the buyers' rush fades into the concrete pores, and again the studio is bare. Throughout the autumn months, the color had washed away in gentle waves, and now only a few paintings remain scattered on the freshly-scrubbed wooden floor. Tools have been put away, the inventory lists have been filed and buried in the safe behind the shed, and the studio doors have closed for the year. Dying leaves and the first buds of snow rap silently at the windows, accompanied steadily by the clock's tired heartbeat.

My father, too, breathes more easily in this quiet. Still we remember the blue that streaked the floor, the echoing clouds of the clanging of flesh, and the soft exchange of our lives for hers. But I do not see blood in this blue paint—I see stars, threads looped infinitely upon themselves, smudged fingers and red-hot fire. My father dots the soldier's head with blue. Inside his canvas they trudge in the dirt, their smocks of manhood tarnished with red. They step over faceless bodies and hunched rifles. They all look the same—stripped of their limbs and their posture, enemies and countrymen writhe in neighboring hovels of dirt. The colors are toned to black, dulled, except for the red that seeps out from everywhere. They are no longer men, except for the red.

The door swings open. The air clenches. The painted soldiers pause mid-death. Bassia stands in the doorframe. She looks perfectly symmetrical, outlined in hard trembling strokes and colored with soft sponges. Her eyes scream sympathy; her hands feign peace.

For a moment nobody moves. We all look at each other.

"They found one of your notebooks.” She speaks in a voice carried by no breath at all. “The police are looking for you. Ars!" She speaks my name and then she hears it. "Ars." I imagine her trapped inside a tear, undulating with its music, the colors of her face whirling into a primal muddle.

She looks at me through this glassy sheet, and maybe she imagines my face as it will look in her sketchbook. It is already over, I am a charcoal representation of bones and flesh, a vaguely outlined remnant of an electrical being.

"My father just phoned the station," she continued, her voice rising. "They're coming now." We don’t move. "I can't run much faster than they can,”—she is shouting now, she has walked up and clutches my arm—“They should be here by now."

But my father is already standing next to me with my books piled neatly in his arms. His bulky hand trembles, very slightly, as he holds my knapsack out for me. Even now, he says nothing, but touches my arm and offers me help. I feel my heart in my throat; I cannot look at him.

I hold Bassia's shoulders and I look at her. I do not kiss her because I must look at her. She whispers something about my mother, about stones and boxes. Then, I run.

The familiar sun, at last, burns orange and the universe is in a state of alarm. Leaves crunch on the ground but do not fall from the sky. The trees are bare, bowing downwards to look at their banished leaves. Like rows of mourners, the trunks hold their vigils on either side of the street, standing still and silent as my feet send puddles of leaves upwards into whirlpools.

Finally her marble headstone gleams orange in the dusk. First it is one in an orchard of glimmering fruits, and then it is the only one, and I am touching it, its solid weight holding up my head because my neck cannot.

Cold tears fall on my cheeks but I do not cry. They come from the sky, falling in eerie vortexes and settling into the grass like dandelion ashes. They are solid but they touch me, and they melt. I do not shiver because I cannot move.

For a time, I wait, and then I begin to dig. I fall on my knees and pull the grass away at its roots, deeper and deeper, until my hands are raw and a hole materializes. I settle my knapsack into this tomb, smooth the clasp over the opening, and it disappears in the dirt which disappears in the snow.

But I am not finished; now I begin to dig again, a hole right beside the one I have just filled up. Beneath the snow I feel the blades of grass, and I remember that Bassia had clapped and that blades of grass had shivered in her soft echo, that it had been so quiet and so silent and so still, and that she had clasped my fingertips and had not said a word. "I'm scared," I had said, "I'll be killed." And nothing in her faltered, nothing grieved. As if she had always thought so; as if this was why she loved me.

I continue to dig, now beneath the grass I find the dirt, and inside the cold my fingertips feel warm.

"Aren't you afraid?" I had asked her, "what if they punish you too?" And she had laughed, had thrown back her head and laughed until the trees shuddered in distress. "They'll never punish me," she had answered—“ because your father is an officer?”—but she only laughed again. "They'll never punish me," and she stroked my face, tracing my chin with the tips of her hands, "because I'm nothing like you."

My mother's gravestone looms above me, silent and gray, while my hands freeze, my knees ache, my fingers burn with the heat of the dead...

"We can't all be like you, Ars."

I keep moving, deeper and deeper, until my forefinger bends on something hard. Faster now—faster—and deeper—and soon it is out, and open, the lid of the metal box flapping angrily in the rising winds.