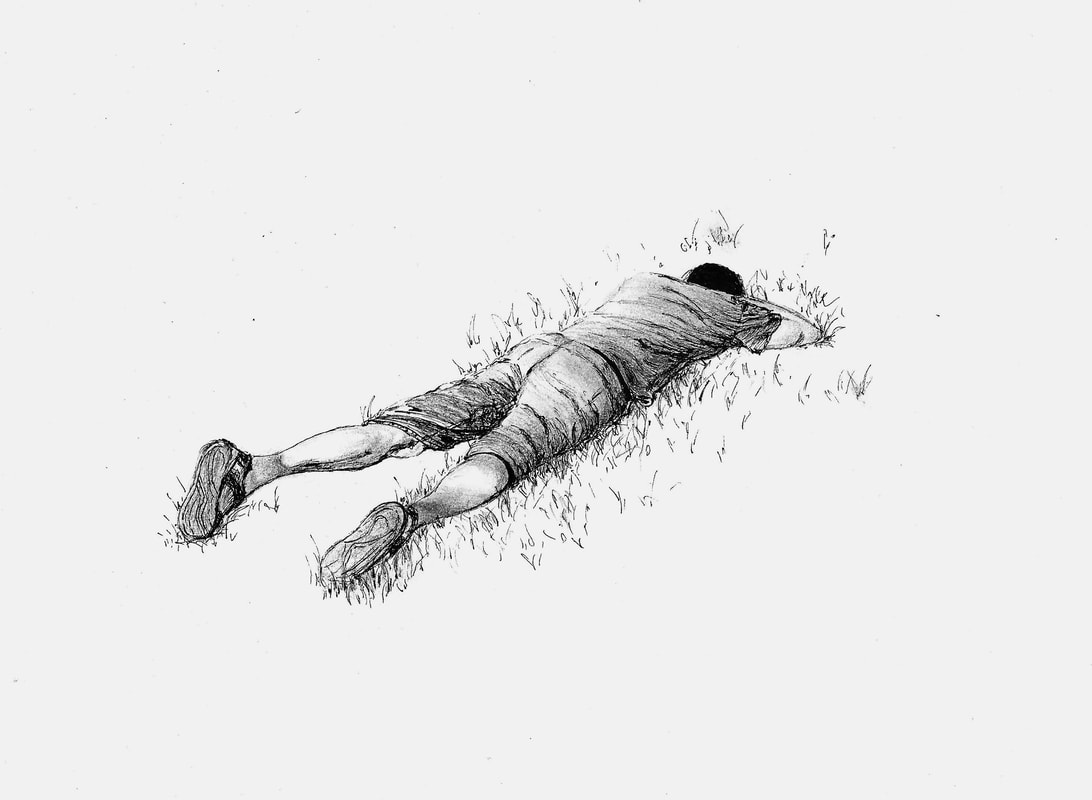

But there was that body. So things could not go on as they naturally would have gone on: the father would have wheeled away the perambulator, the teens would have continued passing around the ball with which they had been playing, the couple would have strolled further down the pathway holding sweaty hands but not letting go if it were not for the body. Indeed, the two doing yoga or practicing some one or other of the martial arts, the thin ginger man jogging, the old lady with a walking stick and the blonde paper-faced girl with a sheep dog, they all would have got on with their leisure if it was not for that queer body down by the stream.

‘And how very typical of the body,’ thought Katka, ‘that it should be the stumbling block, that which we cannot pass over.’ For there it was: unmoving, facing the ground covered with various grasses (carefully trimmed, for this was, after all, the oldest public garden in the country) – the body which none of them could phase out. The headphones were taken off, unplugged, one by one: the music was gone. An old woman came down the left path, dragging her feet and her lazy dog, which sniffed here a plant, there a cobble, then sniffed no more but trotted in semi-circles round the place where everyone was now standing, eyeing the body behind the wooden fence by the stream.

‘We should call the police,’ somebody thought. ‘Perhaps it was a murder,’ thought another. ‘Or someone must have committed suicide,’ concluded the third. ‘The corpse looks fresh,’ someone said. ‘Certainly, it is impossible to say from this distance. We should go over the fence and check,’ contested the former. ‘But we mustn’t touch anything; it is now a crime scene; we had better just call an ambulance and the police,’ said the paper-faced girl, whose dog was getting restless on the leash, so she undid the chain and let it run around the park.

The trees around them were turning yellow, as they should – it was the right season after all, early autumn. Before she turned the corner and walked to the park, Katka had passed by several old churches where people had been standing, for it was Sunday and the mass had just finished. Now she saw, across the park, the crowded street and felt relieved that it was over. (She could not stand this pretended religious devotion which some people still expressed, going to church on Sunday, then living the rest of the days of the week as if god’s word was no more than a chewing gum whose flavour had been long sucked out. She felt nothing whatever for any god; she only loathed the hypocrisy of her times.) Her eyes sank back down to the view of the body which was lying prostrate on the grass. It looked almost like a body of a man in prayer.

But it was not. ‘It must have been a suicide,’ she agreed. She pondered that idea for a while. ‘Perhaps that is how I should end it too, my life,’ she thought, ‘with a suicide. Some day. I think it only natural that one should go when one feels one should; that one should choose one’s moment. If one were to get up at the break of day some morning, have the habitual coffee, a little food, then feel: this is it, this is the peak, let it end now – then one should certainly take hold of that bundle one calls one’s life and let it drop, like sunlight drops on to the grass through the leaves.’ She looked around her; the sunlight had dropped on to the grass, saturating a patch here, there a streak.

There was death and there was life all around; inside one another. ‘Life and death are like two hands to each other,’ she mused. (‘Two sweaty hands,’ she added on the margin of the previous thought, observing the couple who refused to part even at such a moment.) ‘The nails of death are stung deep into the palm of life; the nails of life are stung deep into the palm of death. Like hooks connecting two ropes that hold the bridge – without either, the void would be unsurpassable,’ she concluded. Then she smiled. For there was a change in the scene before her. Having stood next to the couple holding sweaty hands, the two teens with the ball and the father with the perambulator – on the left, and the grandma with the lazy dog, the paper-faced girl, the martial arts practitioners with their long wooden sticks, the ginger jogger and the old lady with the walking cane – on her right, Katka suddenly realised she was standing all alone; everyone had moved on unnoticeably. Looking on she saw the body by the stream stir gradually, until it stood completely erect on the grass and returned her gaze. The dead body; it was the body of a sleeper.

‘And how very typical of the body,’ thought Katka, ‘that it should be the stumbling block, that which we cannot pass over.’ For there it was: unmoving, facing the ground covered with various grasses (carefully trimmed, for this was, after all, the oldest public garden in the country) – the body which none of them could phase out. The headphones were taken off, unplugged, one by one: the music was gone. An old woman came down the left path, dragging her feet and her lazy dog, which sniffed here a plant, there a cobble, then sniffed no more but trotted in semi-circles round the place where everyone was now standing, eyeing the body behind the wooden fence by the stream.

‘We should call the police,’ somebody thought. ‘Perhaps it was a murder,’ thought another. ‘Or someone must have committed suicide,’ concluded the third. ‘The corpse looks fresh,’ someone said. ‘Certainly, it is impossible to say from this distance. We should go over the fence and check,’ contested the former. ‘But we mustn’t touch anything; it is now a crime scene; we had better just call an ambulance and the police,’ said the paper-faced girl, whose dog was getting restless on the leash, so she undid the chain and let it run around the park.

The trees around them were turning yellow, as they should – it was the right season after all, early autumn. Before she turned the corner and walked to the park, Katka had passed by several old churches where people had been standing, for it was Sunday and the mass had just finished. Now she saw, across the park, the crowded street and felt relieved that it was over. (She could not stand this pretended religious devotion which some people still expressed, going to church on Sunday, then living the rest of the days of the week as if god’s word was no more than a chewing gum whose flavour had been long sucked out. She felt nothing whatever for any god; she only loathed the hypocrisy of her times.) Her eyes sank back down to the view of the body which was lying prostrate on the grass. It looked almost like a body of a man in prayer.

But it was not. ‘It must have been a suicide,’ she agreed. She pondered that idea for a while. ‘Perhaps that is how I should end it too, my life,’ she thought, ‘with a suicide. Some day. I think it only natural that one should go when one feels one should; that one should choose one’s moment. If one were to get up at the break of day some morning, have the habitual coffee, a little food, then feel: this is it, this is the peak, let it end now – then one should certainly take hold of that bundle one calls one’s life and let it drop, like sunlight drops on to the grass through the leaves.’ She looked around her; the sunlight had dropped on to the grass, saturating a patch here, there a streak.

There was death and there was life all around; inside one another. ‘Life and death are like two hands to each other,’ she mused. (‘Two sweaty hands,’ she added on the margin of the previous thought, observing the couple who refused to part even at such a moment.) ‘The nails of death are stung deep into the palm of life; the nails of life are stung deep into the palm of death. Like hooks connecting two ropes that hold the bridge – without either, the void would be unsurpassable,’ she concluded. Then she smiled. For there was a change in the scene before her. Having stood next to the couple holding sweaty hands, the two teens with the ball and the father with the perambulator – on the left, and the grandma with the lazy dog, the paper-faced girl, the martial arts practitioners with their long wooden sticks, the ginger jogger and the old lady with the walking cane – on her right, Katka suddenly realised she was standing all alone; everyone had moved on unnoticeably. Looking on she saw the body by the stream stir gradually, until it stood completely erect on the grass and returned her gaze. The dead body; it was the body of a sleeper.

V. B. Borjen (b.1987) writes in two languages and reads in four. His short stories, essays, articles and literary translations have appeared in various Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, Hungarian, and Montenegrin magazines and dailies. The manuscript of his first poetry collection Priručnik za levitiranje (Levitation Manual) won the prestigious Mak Dizdar Award in 2012 and was published the following year to significant acclaim. In the same year his poem "Momento mori" was published in Hypothetical: A Review of Everything Imaginable, followed by a (still informative) interview. He is a doctoral candidate and lives in the Czech Republic, where he reads (on the trams, the trains, the street corners, in the cafes, on the toilet, between the lessons, while queuing or doing the washing up) and writes, Tumblrs his favourite literature and art and Instagrams his own ink drawings and silliness. Tweets as well, but too sporadically.