No sooner had he moved to Farrington on the Isle of Wight than Alfred Lord Tennyson developed a bad cough. At first, he thought it was nothing. He had discovered cigars as an after-dinner practice for gentlemen of distinction who came to dine with the Poet Laureate. Everyone smoked. Everyone coughed. His local physician, Mr. Norrington, advised Tennyson to refrain from brandy with his cigars. The drink only made matters worse. On the advice of Norrington, Tennyson was sent to London in the spring of 1858 to see a chest specialist. There, if all went according to plan, he would be cured of his cough and received by Her Majesty and Prince Albert at Buckingham Palace. Tennyson owed his laureateship to the Prince Consort. He had been impressed with In Memoriam and the poet’s deep, tragic lament for a lost friend. It had given Her Majesty a good weep.

The first stop on Tennyson’s sojourn was the office of Mr. Gadsden Bassingthwaite, a noted Harley Street specialist in matters of the respiratory system. The poet was admitted at 10:38 a.m. and shown to a room where a young man, hunched in the corner, sat listening to a ticking clock on the mantle. Various letters of Tennyson’s reveal how much the poet reviled ticking clocks and hunched young men. The young gentleman nodded in the poet’s direction.

Few men of Tennyson’s age and rank had as much facial hair as the poet had. It was useful to Tennyson because he could hide his thoughts behind it. If his nerves grew frayed, as they were at that moment when the mantle clock ticked to 10:45 and chimed the quarter-hour unexpectedly, Tennyson would run his hand over his pale, bald pate, leaving the tangle of beard and flowing side locks to sort themselves out. Both men had coughing fits in unison at 10:46 a.m. then stared at each other in silence.

“We seem to be suffering from similar maladies,” the young man noted when he regained his composure and put his handkerchief back in his waistcoat pocket.

“I hope for your sake, and for mine, you are not consumptive,” Tennyson said, staring steely-eyed at the gaunt young man.

“No, no. I’m just down from Oxford for a day or so.”

“And the cough has something to do with Oxford?”

“No, no. Whooping cough. I had it before I became a student and it left me with a cough. And you?”

“Cigars,” replied Tennyson. “And dampness. I reside on the Isle of Wight. The sea air is supposed to be good but it makes me hack.”

“Perhaps a combination of the two.”

Tennyson was hoping the young man would not get up and introduce himself, which he did. He feared the soft, cold, clammy hand he would have to shake. The young man extended his hand. He hoped that the young man would not tell him that he was an admirer of In Memoriam. He was. Beads of sweat started to appear on Tennyson’s forehead. He then foresaw what the young man would say next: “I too am a poet.” Tennyson closed his eyes for a moment. The cough was a malady. The young man was proving to be a plague.

Mr. Gadsden Bassingthwaite listened to Tennyson’s breathing through a long, brass tube, and then wrote a note on a piece of paper and handed it to the poet. It was, Tennyson presumed, a prescription for some sort of bitter medicine or, perhaps, a notice to refrain from the gentlemen’s after-dinner habit. Tennyson opened the piece of paper and glanced at it. In the odd, almost poisonous-looking handwriting of Mr. Bassingthwaite was an address.

“This might do you good. Get away from the dampness,” the doctor said. “This is the address of a friend of mine in Shropshire. He is a fine chap. Good family. It will be the perfect place for you to get away to somewhere drier and write in quiet.” Tennyson read the address, memorized it, thanked the doctor, and left, repeating the address to himself. Pothery Manor, Wenington, Shropshire. As he departed the Harley Street rooms, the doctor’s manservant who had opened the door delayed the poet to inquire whether the Isle of Wight would be a suitable disposition for retirement.

Meanwhile, the gaunt young man was summoned into the doctor’s examining room and he, too, exited with a piece of paper of the same size and shape. Both Tennyson and the young man, in one of the great moments of literary coincidence, let their pieces of paper slip from their waistcoat pockets. As they exited the building mere moments apart, each headed in a different direction. Tennyson went toward Oxford Street. The young man headed in the direction of Marylebone.

After seeing the young man out, the doctor appeared from his examination room to inquire about the luncheon appointment he had set for noon in Mayfair, but when he looked down on the floor he found the two pieces of paper the patients had dropped. He picked them up and told the servant to go after them. Not bothering to look to see which piece of paper belonged to which patient, the manservant took off after the only one he could see from the vantage of the front steps. That is how Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, later to be known as Lewis Carroll, was given the address of a country retreat in Shropshire and not a prescription for a laudanum-based cough medicine that would have rendered the young mathematician a hallucinatory, Coleridge-esque, rattle-brain of apparitions.

A week later, at Paddington Station, with a shout of its whistle, the train guffed off toward the west country carrying both Lewis Carroll and Alfred Lord Tennyson toward the same destination. Neither man knew the other was on the train. They did not notice each other though they were the only two passengers to disembark at Wenington on the small country platform with a tiny station house. They each hailed different porters. The porters put each man’s luggage into separate hansoms. At the market cross, Tennyson’s rig went right while Dodgson’s went left, and to the casual observer it appeared neither were headed to the same destination, though there are many ways to arrive at Pothery Manor, a Sixteenth-century stone house set well back from the road.

The master of Pothery, Mr. Joshua Phillbee, came out to greet the visitors. He was an older, stooped man, with large, bushy sideburns, who wore his reading glasses firmly fixed on his forehead. His face bore a permanent expression of surprise as if he had just looked up from his reading with an indescribable realization of dismay. Phillbee had only expected Tennyson. The second guest’s arrival was a complete surprise. Dodgson and Tennyson stepped out of their carriages at the same time. Both men strode up to Mr. Phillbee who had extended his hand, but Tennyson paused, annoyed, and turned to Dodgson.

The hansom drivers began unloading the valises and each helped the other carry the trunks to the front door of the manor.

“Good heavens, man! Are you following me?” Tennyson exclaimed, slightly indignant that his cure should be shared with another man.

“No, certainly not, sir. It would appear that it is you who are following me.”

“I am confused,” Mr. Phillbee said. “I was only expecting Lord Tennyson. Do you two know each other?”

Tennyson snorted, “That young man is stalking me! He is an erstwhile poet. He is hiding behind a gauze of malady! We met in Gadsden Bassingthwaite’ s clinic last week. Did the good doctor possess a bottom drawer full of the same prescriptions?”

Dodgson, embarrassed at the situation, blushed, and his stoop became slightly more evident. He reached into his pocket and produced the doctor’s note and introduced himself to Mr. Phillbee. Phillbee pulled his glasses to his nose and read the message.

“Your Lordship, it appears that Mr. Dodgson here is also our guest at the request of Gadsden Bassingthwaite. If you two have not been formally introduced – Mr. Dodgson, Lord Tennyson. Lord Tennyson, Mr. Dodgson. You are most welcome to join us, Mr. Dodgson. I shall have another place set for your for lunch. That is no inconvenience, and I hope your recuperation will be furthered by your time here.”

The three men headed toward the house, their feet crunching on the cinder path. Tennyson turned to Dodgson, and under his breath muttered, “I have come here for quiet and solitude and I trust you will not inundate me with your verse.”

Dodgson smiled and nodded.

After the repast, Mr. Phillbee described the extended grounds of Pothery Manor and suggested that the two men might find the peace and solitude of a dry afternoon by taking a constitutional on the eastern side of the property. There was a lovely forest there, full of strange and enchanting things that might, he offered, inspire a verse from the Poet Laureate and perhaps a moment of quiet contemplation for the young Oxford student? “I am afraid,” Mr. Phillbee added, “that there is little, though, that you will find to your mathematical curiosity.”

Dodgson simply nodded, aware that his stammer had been evident when he replied to the serving maid that “Yes, I would, indeed, be happy with a second helping of turnips.” Tennyson pretended not to notice the stammer, though he articulated all his words during the remainder of the luncheon conversation not to scold the young man but in a veiled attempt to teach him to enunciate every syllable as if it was a gift from the mind and the mouth.

“If you don’t mind me asking, what interests and unique pursuits do you have, sir,” Phillbee inquired of the young stammerer?

“I am a mathematician. I am a don t Oxford, Christ Church College, and my unique pursuit could be defined as a desire to understand paradoxes and conundrums within the scope of mathematics, geometry, and algebra.”

“I say,” said Tennyson, that’s a unique pursuit.” Dodgson went back to studying his soup. As lunch concluded, Mr. Phillbee excused himself and explained he had been in the middle of a peculiar idea prior to welcoming his guests and he desired, with their permission, to return to it before it grew teeth.

“Teeth,” inquired Dodgson?

“Oh yes. Ideas are treacherous. One minute you are cuddling a lion cub and the next minute it is sinking its fangs in your brain.” Tennyson nodded though his eyebrows were raised in surprise. “Your Lordship may desire a walk. We have splendid walking areas here and Pothery and I dare say if you embark upon them in the next half hour you will wander as lonely as a cloud until dinner time.”

In the hallway, Dodgson was slipping on her overcoat as Tennyson stepped up to the pegged tree.

“I suppose you are going to follow me,” said Tennyson, wrapping his tweed cape around his shoulders and donning his broad-brimmed hat at the front door of the manor.

“May I join you?” asked Dodgson without expecting an answer. “I don’t mean to intrude. I shall be silent as a triangle.”

“Why a triangle,” asked Tennyson?

“Because each side is not squared to the other…”

“You don’t need to tell me more. You shall be silent,” the poet said.

As they passed through the vestibule, Tennyson looked through the transom window. “It may rain on us. I hope you are preparing us for rain, Mr. Dodgson.”

Dodgson looked around. In the umbrella stand was the choice of a woman’s parasol in the most delicate shade of pale maroon, and a large black umbrella, likely of French manufacture, that sported a small brass plate on the handle. Dodgson paused to decipher it as Tennyson stood with the door open. “Do you always stop to read your rain implements?”

“I have never seen this make before. It is heavier than any umbrella I have known. It is, perhaps, Belgian. It says “Verpel.”

“Tennyson glanced at it. “No, I think that V is an R in scrollwork lettering. It says ‘Repel.’ That is a statement of the obvious.” About a hundred yards behind the barn, a lane emerged from the rough of the field and led through a copse where the trees met in a low arch over the passage. The two men walked in silence. The silence made Tennyson uneasy.

“Mr. Dodgson, thank you for holding your silence and not jabbering during our walk. One thing I cannot stand is a jabber walk where someone is talking in my ear. That said, I find it difficult to concentrate with you saying nothing. The silence is as annoying as pointless questions. Please feel free to narrate our constitutional with pertinent thoughts.”

“There is a very large, fat bird over there,” Dodgson noted, pointing to an undergrowth of tangled weeds. “It reminds me of a dodo but it is probably a grouse.”

“Ah, that is a bobolink. Bobolinks, when they fly, squeak.” Tennyson clapped his hands and the large, fat bird took flight with a squeak. “There is no reason at all that they should be able to fly. None at all. In that respect, they are like the lamented dodo. Their body weight is greater than the proportional strength of their wings. As they try to take off, the poor things likely feel a tremendous suffering which is my theory as to why a bobolink squeaks. They are an entirely unpoetic bird, though as God made them. He mitigated their shortcomings with the perseverance and determination to do what they should not be able to do. In order to survive, they must strive, and seek to find, and not yield.”

“That last bit – that would make a good poem. I hope, my Lord, you remember that when you find the opportunity to use it.”

“My dear Dodgson, I remember everything. A long-lost college friend of mine said that I have the eye of an artist. An artist must not merely see, he must remember, but above all, he must enumerate, as Samuel Johnson said, all the wonders of nature, and explain things in their proper context.”

Tennyson paused, removed his hat, and drew his handkerchief from his trousers pocket, and mopped his bald head. The ovoid shape of the poet’s skull reminded Dodgson of a large egg, though he dared not say that. It would not have been polite.

Out of the corner of his eye, Dodgson saw an oversized white hare dart across the lane. “Look!” he exclaimed. “Did you see that?”

Suddenly, as if they were two boys in the woods rather than a Poet Laureate and the mathematician, Tennyson shouted, “Quick! Let’s get after that! Let’s see where it goes.” They took to their heels. The hare paused, sat up on its hind legs, and sensing that the two men might be poachers out to bag the creature as their quarry, sprang as fast as it could into a thicket of hazel boughs where it disappeared into a warren. The opening in the earth, a mouth forming an almost perfect expression of awe, was larger than that of a normal rabbit hole, yet just slightly smaller than a London sewer cover.

The two men reached the edge of the opening. They parted the boughs and stared into the darkness. Tennyson reached into the pocket of his tweed coat, removing first a cigar and then a small brass box of matches. He put the cigar back and was about to strike a match.

“Wait a minute,” said Dodgson, who reached into his overcoat and pulled out two short candles. “Isn’t that handy? You have matches and I have candles.”

“Why, sir, do you carry two candles in your pocket?” asked Tennyson, looking surprised at the young man.

“There’s a rhyme I heard somewhere – ‘How many miles to Babylon?’”

“Yes, I’ve heard it, but that doesn’t answer my question.”

“One to get there and the other back again, and the entire journey is by candlelight.”

“Makes sense to me,” Tennyson replied as he lit both candles. Dodgson held his taper just inside the threshold of the rabbit hole. He gasped and pulled out his head.

“My eyes must be playing tricks on me, but I do behold a monastery in there.”

“A monastery? Come now. What would a monastery be doing in a rabbit hole?”

Dodgson stared at Tennyson for a moment and then it occurred to him. “Perhaps in there is the outside of the world and we in our present state, as we are and where we are, are in the inside. Perhaps it is bigger on the inside than on the outside. It is possible, I believe, though no one has proven that yet, mathematically speaking, of course. That would explain the appearance of vaulted Gothic arches.”

Tennyson had to see for himself. He peered inside and moved his candle back and forth as the shadows of the pillars twisted on the walls of the inner chamber. “I think, sir, we may have stumbled upon the lost ruins of Camelot!”

“Shall we investigate?” asked Dodgson.

“Indeed, sir, we must! Please. You first. You are younger and stronger than I. After you.”

“Oh, I insist – you first, my Lord. You are much braver than I, and your lungs are better than mine. I am gasping with surprise and anticipation and the air in there might be to rank for us.”

“Mr. Dodgson, we both accept the treatment of the same respiratory physician, so I recommend that you go first and if you get into any trouble, I will pull you out. I will do you the honor of rescuing you.”

Tennyson held both candles and the umbrella Dodgson had brought with him while Dodgson wrapped his long overcoat around the middle of his body and crawled into the hole. Tennyson passed the candles and umbrella to Dodgson and wiggled in after him. With both candles raised, the two men beheld a spectacle. The chamber in which they stood contained a low, vaulted ceiling that led down a flight of steps into a large crypt-like room. The walls were carved with gargoyles and the pillars were festooned in twists of stone. The floor was clean from debris, and the air, for being so far below ground-level as they descended, was still pure and fresh. They moved forward cautiously.

“Yes!” exclaimed Tennyson, “This is the remains of long-lost Camelot! We have stumbled across the seat of Arthur!”

“I do not think these are the remains of Camelot,” Dodgson noted in a whisper. “I keep thinking where I have seen these pillars before. I’ve seen the like in the Temple Bar in London. I believe we have stumbled upon a Templar structure of some sort.”

Tennyson nodded. The place seemed the epitome of quiet and calm, but there was an eerie solitude about it that made him feel uneasy.

“You are breathing heavily, my friend,” he said to Dodgson. Dodgson held his breath for a moment. Tennyson did likewise. They listened. They looked at each other, each reading the other’s mind. If it is not you, then who is making that sound?

Tennyson turned slowly, raising his candle above his shoulder to let more light flood the room. Dodgson turned in time to gasp with the poet.

An enormous dragon reared up on its hind legs and sent from its nostrils a twinned stream of fire that curled as it struck the stone wall in a vortex of flame and smoke. The beast was green and its skin iridescent in the candlelight. The feet were armored in enormous grey claws, and its tail was spiked with spears that smashed against the pillars to either side of the passageway. Its eyes flared like two explosions of light, and its lips were curled over protruding fangs in the most unpleasant expression of rage.

The two men screamed and ran deeper into the cavern, taking refuge behind a pillar and clutching their candles. They heard the creature’s footsteps treading heavily on the stone floor, each one falling with a thud.

“Should we not extinguish our candles?” Dodgson asked.

“I, sir, do not wish to perish in the dark! Dear God in heaven, what have we gotten ourselves into?” Tennyson realized his voice was loud with fear and tried to whisper the latter portion of his statement, but the beast heard him and spun around.

“Run!” yelled Dodgson. “I shall fend him off so you can make your escape!”

“I am not leaving you!”

But before he could say another word, Dodgson was in the middle of the aisle, hemmed in by pillars to either side of him. The dragon snorted and shot another stream of fire into the stone vaulted ceiling. Dodgson raised his umbrella and lunged at the beast. On his first strike, the umbrella’s point bent on the dragon’s breastplate of scales. The rain device opened by itself on impact, and the beast looked down in surprise, frightened by the snicker-snack of the rain shield as it snapped to full span. Dodgson pulled back and looked at the umbrella, its arms like bat-wings stretching a taut black skin in the half-light.

“That’s not going to help,” yelled Tennyson. “He isn’t going to rain on you!”

Dodgson shook the open Repel at the beast, but it was a pointless gesture. Another lick of flame issued from the dragon’s snout and shriveled the black silk to a crisp. Dodgson tried to throw it away, but the handle came loose from the shaft and he realized, much to his amazement, that the Repel contained a sword scabbarded in its shaft. With a second lunge at the dragon, moving from one side of the demon to another but keeping close enough to the scaly stomach that the dragon would risk burning itself, Dodgson began to think their situation was hopeless. He and Tennyson were trapped. They were facing an improbable fate from a creature of legend. He needed a strategy.

It was then Tennyson stepped forward into the passageway. He held his candle high, waving it back and forth, perhaps to taunt and distract the beast or perhaps in an act of stupefying bravery. At that instant, Dodgson spotted a patch on the beast’s side where the dragon had shed a scale. He raised his sword and rammed it into the unprotected spot.

The creature let out a horrific scream as Dodgson let go of the sword, leaving the crook handle of the umbrella jutting from the creature’s side. As both men backed away, the monster fell face-first on the floor, heaved a sigh of smoke, and its eyelids slowly closed.

“You have slain a dragon, my friend!” Tennyson shouted as he moved toward the dead nightmare on the floor. “Bravo! Bravo! Let’s get out of here in case it has a brother.”

Dodgson sank to his knees, exhausted, out of breath, and stunned. “Thank you for raising your candle at the last minute. The light…the light helped me to see where to strike.” Tennyson grabbed Dodgson under the arm and lifted him to his feet.

The two men ran back to the rabbit hole. Their candles were almost down to stubs, and the smoke from the dragon had soured the air. As they shimmied through the hole and brushed themselves off – they were both covered in dirt from entering and exiting the portal – they looked at each other in stunned disbelief and fell back on the ground beneath the hazel boughs. They were breathing heavily and began to laugh hysterically.

“What freak of nature was that?” asked Tennyson. “I thought we were going to be toast. All I could picture in my mind was holding a piece of bread in a pair of tongs over the fire.”

“You, sir, have a very vivid imagination. I kept imagining that the dragon was going to bite my head off. It was probably thinking ‘Off with his head!’”

They lay on the ground, panting and trying to recover themselves, laughing, then falling silent. Tennyson’s expression changed from elation to concern.

“By God, sir, I thought we were going to die in there,” Dodgson said. “They will never believe us when we tell them.”

The two men turned around to stare at the rabbit hole. The hazel boughs were growing back as if by magic and covering the entrance in a tangle of overgrowth until there was no visible evidence of the hole.

“But we won’t, we can’t. Look, my young friend: we crawled into a rabbit hole. It was much bigger on the inside than on the outside, and the place contained a lost medieval monastery, but not any medieval monastery but presumably a Templar hide-away, and inside this insane place, there was a dragon that chased us about and tried to reduce us to ashes until you stabbed it with an umbrella. Can you imagine the headline in The Times? POET LAUREATE AND MATHEMATICIAN LOSE THEIR MINDS IN A RABBIT HOLE. Any word of this would ruin us. Even though we just lived it all, and are recovering in breathless excitement from the battle, it is a lunatic fantasy, especially the part about going into a rabbit hole. Mr. Dodgson, you can’t say a word about this to anyone. No one would believe such a story, not even a child. Fairy tales and fantasies are not the measures of our age. As much as we would like to dream or even to experience our dreams as reality, people will point to us in disbelief. And until someone can come up with a good explanation for dreams, we have nothing to go on but the shakiest fragments of our word of honor as gentlemen. Dragons and gentlemen simply do not mix well.”

Dodgson stopped laughing. “But it is such a great story.” Then, he paused and thought about it. “You’re right, you know. They will lock us up. And look –”

“You know,” said Dodgson with a heavy note of lament in his voice, “no matter what we say, you’re right, they won’t believe us. They’ll say it is all in our imaginations. But saying that, I feel I learned so much this afternoon. It is growing in my mind, and I know it will find its expression someday, in some way.”

Tennyson and Dodgson walked in silence together back to Pothery Manor. They felt the exhilaration of victory tinged with the pall of defeat. “I know now how Arthur must have felt as he fought his final battle,” Tennyson reflected. “He stood tall in a miasma, and no one bore witness to his noble fight. We shall think of this day as one thinks of the great, lost battles of history.”

That evening, when neither man spoke about their outing to the woodlands of Pothery Manor, Mr. Phillbee assumed that the poet and the mathematician had experienced a falling-out of some kind on their constitutional. His suspicions were confirmed when Dodgson packed up his things and, thanking Mr. Phillbee for his hospitality, announced that he would return to London on the morning train. He apologized for what must have been a mix-up of prescriptions by Mr. Bassingthwaite, and for imposing himself on Mr. Phillbee’s hospitality.

Alfred Lord Tennyson and Charles Dodgson would never meet again.

They did, however, exchange a brief correspondence during the first week of December in 1865 shortly after the publication of Alice in Wonderland. Tennyson wrote from his home on the Isle of Wight to congratulate Dodgson, or should one say Lewis Carroll, on the publication of his unusual tale of rabbit holes.

My Dear Dodgson: I thought we had an agreement that we would

never speak of the events at P------ Manor, but it appears that you

have found a useful purpose for the experiences, and in reminiscing

about them in my moments of quiet introspection, I see that I, too,

now understand where some of my thoughts have led me. I have

just returned from London where my mind was focussed on a

manuscript in the British Library that has only recently become

intelligible to a modern mind. It is known as Cotton MS Vitellius

XV, and it describes an ancient hero who slays not one dragon

or even two, but three dragons. I believe he is our St. George, and

that this ancient poem may be our great, missing, national

epic. The protagonist’s name is Beowulf, and I am the first poet

in almost a thousand years to read it. My Idylls of the King is now

complete, and I must admit that I have borrowed from my wildest

imaginings, as I am certain you have. Congratulations on your

new book. Sincerely, T.

Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, wrote back with two words as the body of his message:

Thank you. CD.

He added a postscript to the letter:

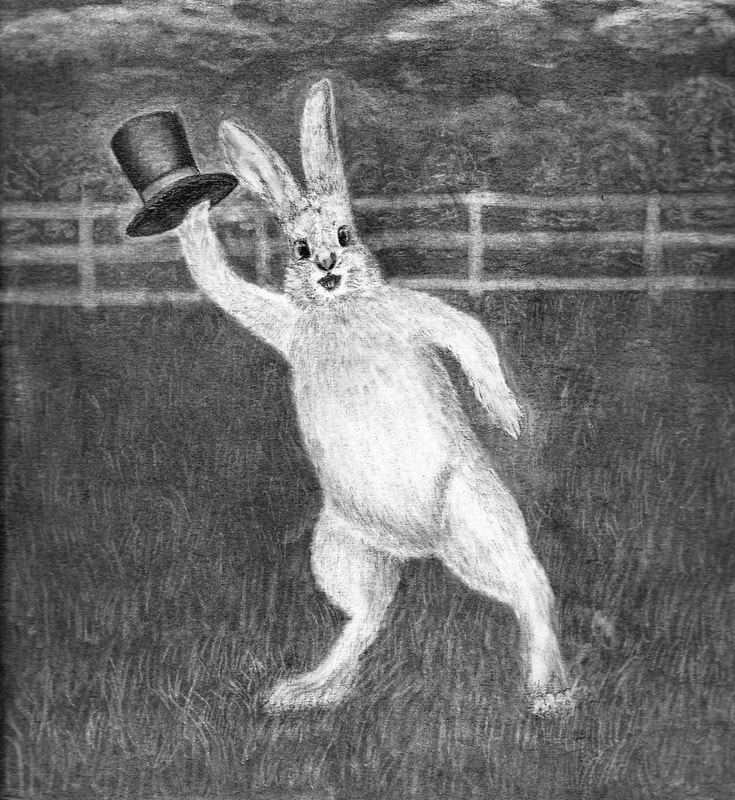

Strange but on my departure from the place, I looked out the

window of the hansom. Even though it was raining heavily,

I saw an enormous white rabbit hurrying along beside me,

perhaps racing my rig to see who would arrive first at my desk

– he or I. I tipped my hat to the aforesaid white Oryctolagus

cuniculus, and he appeared to stop and wave me on in a most

honorable salute. Please treasure our correspondence for the

length of time it would take to fall down a rabbit hole and then

put the matter to the dragon’s breath.

That is the story that has emerged from considerable scholarship. Neither Tennyson nor Lewis Carroll destroyed their correspondence, though both put a one-hundred-and-twenty-year embargo on the letters.

The story should end here with two well-known personages of a by-gone era winking at each other from the feathery hands of their elegant Victorian scripts, except for one small fact that recently came to light and, for the life of me, dear Reader, I cannot keep from you.

In January 2017, a rabbit hole was discovered on an estate in Shropshire (and this is a true story – I would not deceive you), that when entered revealed a large, long-forgotten Templar hideaway with chamber after chamber leading into the darkness of the deep below the tranquil landscape of the West Country. Amid the spiral pillars and the inexplicable delicacy of the vaulted ceilings – all hallmarks of the long-lost order of unlucky knights – some odd bones were found that are currently undergoing extensive testing at the Museum of Natural History in London. Among the debris of calcified remains were found the rusted skeleton of a Victorian umbrella, and a long, sword-like instrument with a brass plate affixed to a curved handle. The brass plate was cleaned so it could be read, and, on close inspection, the word ‘Vorpel’ emerged beneath the layers of tarnish.

The first stop on Tennyson’s sojourn was the office of Mr. Gadsden Bassingthwaite, a noted Harley Street specialist in matters of the respiratory system. The poet was admitted at 10:38 a.m. and shown to a room where a young man, hunched in the corner, sat listening to a ticking clock on the mantle. Various letters of Tennyson’s reveal how much the poet reviled ticking clocks and hunched young men. The young gentleman nodded in the poet’s direction.

Few men of Tennyson’s age and rank had as much facial hair as the poet had. It was useful to Tennyson because he could hide his thoughts behind it. If his nerves grew frayed, as they were at that moment when the mantle clock ticked to 10:45 and chimed the quarter-hour unexpectedly, Tennyson would run his hand over his pale, bald pate, leaving the tangle of beard and flowing side locks to sort themselves out. Both men had coughing fits in unison at 10:46 a.m. then stared at each other in silence.

“We seem to be suffering from similar maladies,” the young man noted when he regained his composure and put his handkerchief back in his waistcoat pocket.

“I hope for your sake, and for mine, you are not consumptive,” Tennyson said, staring steely-eyed at the gaunt young man.

“No, no. I’m just down from Oxford for a day or so.”

“And the cough has something to do with Oxford?”

“No, no. Whooping cough. I had it before I became a student and it left me with a cough. And you?”

“Cigars,” replied Tennyson. “And dampness. I reside on the Isle of Wight. The sea air is supposed to be good but it makes me hack.”

“Perhaps a combination of the two.”

Tennyson was hoping the young man would not get up and introduce himself, which he did. He feared the soft, cold, clammy hand he would have to shake. The young man extended his hand. He hoped that the young man would not tell him that he was an admirer of In Memoriam. He was. Beads of sweat started to appear on Tennyson’s forehead. He then foresaw what the young man would say next: “I too am a poet.” Tennyson closed his eyes for a moment. The cough was a malady. The young man was proving to be a plague.

Mr. Gadsden Bassingthwaite listened to Tennyson’s breathing through a long, brass tube, and then wrote a note on a piece of paper and handed it to the poet. It was, Tennyson presumed, a prescription for some sort of bitter medicine or, perhaps, a notice to refrain from the gentlemen’s after-dinner habit. Tennyson opened the piece of paper and glanced at it. In the odd, almost poisonous-looking handwriting of Mr. Bassingthwaite was an address.

“This might do you good. Get away from the dampness,” the doctor said. “This is the address of a friend of mine in Shropshire. He is a fine chap. Good family. It will be the perfect place for you to get away to somewhere drier and write in quiet.” Tennyson read the address, memorized it, thanked the doctor, and left, repeating the address to himself. Pothery Manor, Wenington, Shropshire. As he departed the Harley Street rooms, the doctor’s manservant who had opened the door delayed the poet to inquire whether the Isle of Wight would be a suitable disposition for retirement.

Meanwhile, the gaunt young man was summoned into the doctor’s examining room and he, too, exited with a piece of paper of the same size and shape. Both Tennyson and the young man, in one of the great moments of literary coincidence, let their pieces of paper slip from their waistcoat pockets. As they exited the building mere moments apart, each headed in a different direction. Tennyson went toward Oxford Street. The young man headed in the direction of Marylebone.

After seeing the young man out, the doctor appeared from his examination room to inquire about the luncheon appointment he had set for noon in Mayfair, but when he looked down on the floor he found the two pieces of paper the patients had dropped. He picked them up and told the servant to go after them. Not bothering to look to see which piece of paper belonged to which patient, the manservant took off after the only one he could see from the vantage of the front steps. That is how Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, later to be known as Lewis Carroll, was given the address of a country retreat in Shropshire and not a prescription for a laudanum-based cough medicine that would have rendered the young mathematician a hallucinatory, Coleridge-esque, rattle-brain of apparitions.

A week later, at Paddington Station, with a shout of its whistle, the train guffed off toward the west country carrying both Lewis Carroll and Alfred Lord Tennyson toward the same destination. Neither man knew the other was on the train. They did not notice each other though they were the only two passengers to disembark at Wenington on the small country platform with a tiny station house. They each hailed different porters. The porters put each man’s luggage into separate hansoms. At the market cross, Tennyson’s rig went right while Dodgson’s went left, and to the casual observer it appeared neither were headed to the same destination, though there are many ways to arrive at Pothery Manor, a Sixteenth-century stone house set well back from the road.

The master of Pothery, Mr. Joshua Phillbee, came out to greet the visitors. He was an older, stooped man, with large, bushy sideburns, who wore his reading glasses firmly fixed on his forehead. His face bore a permanent expression of surprise as if he had just looked up from his reading with an indescribable realization of dismay. Phillbee had only expected Tennyson. The second guest’s arrival was a complete surprise. Dodgson and Tennyson stepped out of their carriages at the same time. Both men strode up to Mr. Phillbee who had extended his hand, but Tennyson paused, annoyed, and turned to Dodgson.

The hansom drivers began unloading the valises and each helped the other carry the trunks to the front door of the manor.

“Good heavens, man! Are you following me?” Tennyson exclaimed, slightly indignant that his cure should be shared with another man.

“No, certainly not, sir. It would appear that it is you who are following me.”

“I am confused,” Mr. Phillbee said. “I was only expecting Lord Tennyson. Do you two know each other?”

Tennyson snorted, “That young man is stalking me! He is an erstwhile poet. He is hiding behind a gauze of malady! We met in Gadsden Bassingthwaite’ s clinic last week. Did the good doctor possess a bottom drawer full of the same prescriptions?”

Dodgson, embarrassed at the situation, blushed, and his stoop became slightly more evident. He reached into his pocket and produced the doctor’s note and introduced himself to Mr. Phillbee. Phillbee pulled his glasses to his nose and read the message.

“Your Lordship, it appears that Mr. Dodgson here is also our guest at the request of Gadsden Bassingthwaite. If you two have not been formally introduced – Mr. Dodgson, Lord Tennyson. Lord Tennyson, Mr. Dodgson. You are most welcome to join us, Mr. Dodgson. I shall have another place set for your for lunch. That is no inconvenience, and I hope your recuperation will be furthered by your time here.”

The three men headed toward the house, their feet crunching on the cinder path. Tennyson turned to Dodgson, and under his breath muttered, “I have come here for quiet and solitude and I trust you will not inundate me with your verse.”

Dodgson smiled and nodded.

After the repast, Mr. Phillbee described the extended grounds of Pothery Manor and suggested that the two men might find the peace and solitude of a dry afternoon by taking a constitutional on the eastern side of the property. There was a lovely forest there, full of strange and enchanting things that might, he offered, inspire a verse from the Poet Laureate and perhaps a moment of quiet contemplation for the young Oxford student? “I am afraid,” Mr. Phillbee added, “that there is little, though, that you will find to your mathematical curiosity.”

Dodgson simply nodded, aware that his stammer had been evident when he replied to the serving maid that “Yes, I would, indeed, be happy with a second helping of turnips.” Tennyson pretended not to notice the stammer, though he articulated all his words during the remainder of the luncheon conversation not to scold the young man but in a veiled attempt to teach him to enunciate every syllable as if it was a gift from the mind and the mouth.

“If you don’t mind me asking, what interests and unique pursuits do you have, sir,” Phillbee inquired of the young stammerer?

“I am a mathematician. I am a don t Oxford, Christ Church College, and my unique pursuit could be defined as a desire to understand paradoxes and conundrums within the scope of mathematics, geometry, and algebra.”

“I say,” said Tennyson, that’s a unique pursuit.” Dodgson went back to studying his soup. As lunch concluded, Mr. Phillbee excused himself and explained he had been in the middle of a peculiar idea prior to welcoming his guests and he desired, with their permission, to return to it before it grew teeth.

“Teeth,” inquired Dodgson?

“Oh yes. Ideas are treacherous. One minute you are cuddling a lion cub and the next minute it is sinking its fangs in your brain.” Tennyson nodded though his eyebrows were raised in surprise. “Your Lordship may desire a walk. We have splendid walking areas here and Pothery and I dare say if you embark upon them in the next half hour you will wander as lonely as a cloud until dinner time.”

In the hallway, Dodgson was slipping on her overcoat as Tennyson stepped up to the pegged tree.

“I suppose you are going to follow me,” said Tennyson, wrapping his tweed cape around his shoulders and donning his broad-brimmed hat at the front door of the manor.

“May I join you?” asked Dodgson without expecting an answer. “I don’t mean to intrude. I shall be silent as a triangle.”

“Why a triangle,” asked Tennyson?

“Because each side is not squared to the other…”

“You don’t need to tell me more. You shall be silent,” the poet said.

As they passed through the vestibule, Tennyson looked through the transom window. “It may rain on us. I hope you are preparing us for rain, Mr. Dodgson.”

Dodgson looked around. In the umbrella stand was the choice of a woman’s parasol in the most delicate shade of pale maroon, and a large black umbrella, likely of French manufacture, that sported a small brass plate on the handle. Dodgson paused to decipher it as Tennyson stood with the door open. “Do you always stop to read your rain implements?”

“I have never seen this make before. It is heavier than any umbrella I have known. It is, perhaps, Belgian. It says “Verpel.”

“Tennyson glanced at it. “No, I think that V is an R in scrollwork lettering. It says ‘Repel.’ That is a statement of the obvious.” About a hundred yards behind the barn, a lane emerged from the rough of the field and led through a copse where the trees met in a low arch over the passage. The two men walked in silence. The silence made Tennyson uneasy.

“Mr. Dodgson, thank you for holding your silence and not jabbering during our walk. One thing I cannot stand is a jabber walk where someone is talking in my ear. That said, I find it difficult to concentrate with you saying nothing. The silence is as annoying as pointless questions. Please feel free to narrate our constitutional with pertinent thoughts.”

“There is a very large, fat bird over there,” Dodgson noted, pointing to an undergrowth of tangled weeds. “It reminds me of a dodo but it is probably a grouse.”

“Ah, that is a bobolink. Bobolinks, when they fly, squeak.” Tennyson clapped his hands and the large, fat bird took flight with a squeak. “There is no reason at all that they should be able to fly. None at all. In that respect, they are like the lamented dodo. Their body weight is greater than the proportional strength of their wings. As they try to take off, the poor things likely feel a tremendous suffering which is my theory as to why a bobolink squeaks. They are an entirely unpoetic bird, though as God made them. He mitigated their shortcomings with the perseverance and determination to do what they should not be able to do. In order to survive, they must strive, and seek to find, and not yield.”

“That last bit – that would make a good poem. I hope, my Lord, you remember that when you find the opportunity to use it.”

“My dear Dodgson, I remember everything. A long-lost college friend of mine said that I have the eye of an artist. An artist must not merely see, he must remember, but above all, he must enumerate, as Samuel Johnson said, all the wonders of nature, and explain things in their proper context.”

Tennyson paused, removed his hat, and drew his handkerchief from his trousers pocket, and mopped his bald head. The ovoid shape of the poet’s skull reminded Dodgson of a large egg, though he dared not say that. It would not have been polite.

Out of the corner of his eye, Dodgson saw an oversized white hare dart across the lane. “Look!” he exclaimed. “Did you see that?”

Suddenly, as if they were two boys in the woods rather than a Poet Laureate and the mathematician, Tennyson shouted, “Quick! Let’s get after that! Let’s see where it goes.” They took to their heels. The hare paused, sat up on its hind legs, and sensing that the two men might be poachers out to bag the creature as their quarry, sprang as fast as it could into a thicket of hazel boughs where it disappeared into a warren. The opening in the earth, a mouth forming an almost perfect expression of awe, was larger than that of a normal rabbit hole, yet just slightly smaller than a London sewer cover.

The two men reached the edge of the opening. They parted the boughs and stared into the darkness. Tennyson reached into the pocket of his tweed coat, removing first a cigar and then a small brass box of matches. He put the cigar back and was about to strike a match.

“Wait a minute,” said Dodgson, who reached into his overcoat and pulled out two short candles. “Isn’t that handy? You have matches and I have candles.”

“Why, sir, do you carry two candles in your pocket?” asked Tennyson, looking surprised at the young man.

“There’s a rhyme I heard somewhere – ‘How many miles to Babylon?’”

“Yes, I’ve heard it, but that doesn’t answer my question.”

“One to get there and the other back again, and the entire journey is by candlelight.”

“Makes sense to me,” Tennyson replied as he lit both candles. Dodgson held his taper just inside the threshold of the rabbit hole. He gasped and pulled out his head.

“My eyes must be playing tricks on me, but I do behold a monastery in there.”

“A monastery? Come now. What would a monastery be doing in a rabbit hole?”

Dodgson stared at Tennyson for a moment and then it occurred to him. “Perhaps in there is the outside of the world and we in our present state, as we are and where we are, are in the inside. Perhaps it is bigger on the inside than on the outside. It is possible, I believe, though no one has proven that yet, mathematically speaking, of course. That would explain the appearance of vaulted Gothic arches.”

Tennyson had to see for himself. He peered inside and moved his candle back and forth as the shadows of the pillars twisted on the walls of the inner chamber. “I think, sir, we may have stumbled upon the lost ruins of Camelot!”

“Shall we investigate?” asked Dodgson.

“Indeed, sir, we must! Please. You first. You are younger and stronger than I. After you.”

“Oh, I insist – you first, my Lord. You are much braver than I, and your lungs are better than mine. I am gasping with surprise and anticipation and the air in there might be to rank for us.”

“Mr. Dodgson, we both accept the treatment of the same respiratory physician, so I recommend that you go first and if you get into any trouble, I will pull you out. I will do you the honor of rescuing you.”

Tennyson held both candles and the umbrella Dodgson had brought with him while Dodgson wrapped his long overcoat around the middle of his body and crawled into the hole. Tennyson passed the candles and umbrella to Dodgson and wiggled in after him. With both candles raised, the two men beheld a spectacle. The chamber in which they stood contained a low, vaulted ceiling that led down a flight of steps into a large crypt-like room. The walls were carved with gargoyles and the pillars were festooned in twists of stone. The floor was clean from debris, and the air, for being so far below ground-level as they descended, was still pure and fresh. They moved forward cautiously.

“Yes!” exclaimed Tennyson, “This is the remains of long-lost Camelot! We have stumbled across the seat of Arthur!”

“I do not think these are the remains of Camelot,” Dodgson noted in a whisper. “I keep thinking where I have seen these pillars before. I’ve seen the like in the Temple Bar in London. I believe we have stumbled upon a Templar structure of some sort.”

Tennyson nodded. The place seemed the epitome of quiet and calm, but there was an eerie solitude about it that made him feel uneasy.

“You are breathing heavily, my friend,” he said to Dodgson. Dodgson held his breath for a moment. Tennyson did likewise. They listened. They looked at each other, each reading the other’s mind. If it is not you, then who is making that sound?

Tennyson turned slowly, raising his candle above his shoulder to let more light flood the room. Dodgson turned in time to gasp with the poet.

An enormous dragon reared up on its hind legs and sent from its nostrils a twinned stream of fire that curled as it struck the stone wall in a vortex of flame and smoke. The beast was green and its skin iridescent in the candlelight. The feet were armored in enormous grey claws, and its tail was spiked with spears that smashed against the pillars to either side of the passageway. Its eyes flared like two explosions of light, and its lips were curled over protruding fangs in the most unpleasant expression of rage.

The two men screamed and ran deeper into the cavern, taking refuge behind a pillar and clutching their candles. They heard the creature’s footsteps treading heavily on the stone floor, each one falling with a thud.

“Should we not extinguish our candles?” Dodgson asked.

“I, sir, do not wish to perish in the dark! Dear God in heaven, what have we gotten ourselves into?” Tennyson realized his voice was loud with fear and tried to whisper the latter portion of his statement, but the beast heard him and spun around.

“Run!” yelled Dodgson. “I shall fend him off so you can make your escape!”

“I am not leaving you!”

But before he could say another word, Dodgson was in the middle of the aisle, hemmed in by pillars to either side of him. The dragon snorted and shot another stream of fire into the stone vaulted ceiling. Dodgson raised his umbrella and lunged at the beast. On his first strike, the umbrella’s point bent on the dragon’s breastplate of scales. The rain device opened by itself on impact, and the beast looked down in surprise, frightened by the snicker-snack of the rain shield as it snapped to full span. Dodgson pulled back and looked at the umbrella, its arms like bat-wings stretching a taut black skin in the half-light.

“That’s not going to help,” yelled Tennyson. “He isn’t going to rain on you!”

Dodgson shook the open Repel at the beast, but it was a pointless gesture. Another lick of flame issued from the dragon’s snout and shriveled the black silk to a crisp. Dodgson tried to throw it away, but the handle came loose from the shaft and he realized, much to his amazement, that the Repel contained a sword scabbarded in its shaft. With a second lunge at the dragon, moving from one side of the demon to another but keeping close enough to the scaly stomach that the dragon would risk burning itself, Dodgson began to think their situation was hopeless. He and Tennyson were trapped. They were facing an improbable fate from a creature of legend. He needed a strategy.

It was then Tennyson stepped forward into the passageway. He held his candle high, waving it back and forth, perhaps to taunt and distract the beast or perhaps in an act of stupefying bravery. At that instant, Dodgson spotted a patch on the beast’s side where the dragon had shed a scale. He raised his sword and rammed it into the unprotected spot.

The creature let out a horrific scream as Dodgson let go of the sword, leaving the crook handle of the umbrella jutting from the creature’s side. As both men backed away, the monster fell face-first on the floor, heaved a sigh of smoke, and its eyelids slowly closed.

“You have slain a dragon, my friend!” Tennyson shouted as he moved toward the dead nightmare on the floor. “Bravo! Bravo! Let’s get out of here in case it has a brother.”

Dodgson sank to his knees, exhausted, out of breath, and stunned. “Thank you for raising your candle at the last minute. The light…the light helped me to see where to strike.” Tennyson grabbed Dodgson under the arm and lifted him to his feet.

The two men ran back to the rabbit hole. Their candles were almost down to stubs, and the smoke from the dragon had soured the air. As they shimmied through the hole and brushed themselves off – they were both covered in dirt from entering and exiting the portal – they looked at each other in stunned disbelief and fell back on the ground beneath the hazel boughs. They were breathing heavily and began to laugh hysterically.

“What freak of nature was that?” asked Tennyson. “I thought we were going to be toast. All I could picture in my mind was holding a piece of bread in a pair of tongs over the fire.”

“You, sir, have a very vivid imagination. I kept imagining that the dragon was going to bite my head off. It was probably thinking ‘Off with his head!’”

They lay on the ground, panting and trying to recover themselves, laughing, then falling silent. Tennyson’s expression changed from elation to concern.

“By God, sir, I thought we were going to die in there,” Dodgson said. “They will never believe us when we tell them.”

The two men turned around to stare at the rabbit hole. The hazel boughs were growing back as if by magic and covering the entrance in a tangle of overgrowth until there was no visible evidence of the hole.

“But we won’t, we can’t. Look, my young friend: we crawled into a rabbit hole. It was much bigger on the inside than on the outside, and the place contained a lost medieval monastery, but not any medieval monastery but presumably a Templar hide-away, and inside this insane place, there was a dragon that chased us about and tried to reduce us to ashes until you stabbed it with an umbrella. Can you imagine the headline in The Times? POET LAUREATE AND MATHEMATICIAN LOSE THEIR MINDS IN A RABBIT HOLE. Any word of this would ruin us. Even though we just lived it all, and are recovering in breathless excitement from the battle, it is a lunatic fantasy, especially the part about going into a rabbit hole. Mr. Dodgson, you can’t say a word about this to anyone. No one would believe such a story, not even a child. Fairy tales and fantasies are not the measures of our age. As much as we would like to dream or even to experience our dreams as reality, people will point to us in disbelief. And until someone can come up with a good explanation for dreams, we have nothing to go on but the shakiest fragments of our word of honor as gentlemen. Dragons and gentlemen simply do not mix well.”

Dodgson stopped laughing. “But it is such a great story.” Then, he paused and thought about it. “You’re right, you know. They will lock us up. And look –”

“You know,” said Dodgson with a heavy note of lament in his voice, “no matter what we say, you’re right, they won’t believe us. They’ll say it is all in our imaginations. But saying that, I feel I learned so much this afternoon. It is growing in my mind, and I know it will find its expression someday, in some way.”

Tennyson and Dodgson walked in silence together back to Pothery Manor. They felt the exhilaration of victory tinged with the pall of defeat. “I know now how Arthur must have felt as he fought his final battle,” Tennyson reflected. “He stood tall in a miasma, and no one bore witness to his noble fight. We shall think of this day as one thinks of the great, lost battles of history.”

That evening, when neither man spoke about their outing to the woodlands of Pothery Manor, Mr. Phillbee assumed that the poet and the mathematician had experienced a falling-out of some kind on their constitutional. His suspicions were confirmed when Dodgson packed up his things and, thanking Mr. Phillbee for his hospitality, announced that he would return to London on the morning train. He apologized for what must have been a mix-up of prescriptions by Mr. Bassingthwaite, and for imposing himself on Mr. Phillbee’s hospitality.

Alfred Lord Tennyson and Charles Dodgson would never meet again.

They did, however, exchange a brief correspondence during the first week of December in 1865 shortly after the publication of Alice in Wonderland. Tennyson wrote from his home on the Isle of Wight to congratulate Dodgson, or should one say Lewis Carroll, on the publication of his unusual tale of rabbit holes.

My Dear Dodgson: I thought we had an agreement that we would

never speak of the events at P------ Manor, but it appears that you

have found a useful purpose for the experiences, and in reminiscing

about them in my moments of quiet introspection, I see that I, too,

now understand where some of my thoughts have led me. I have

just returned from London where my mind was focussed on a

manuscript in the British Library that has only recently become

intelligible to a modern mind. It is known as Cotton MS Vitellius

XV, and it describes an ancient hero who slays not one dragon

or even two, but three dragons. I believe he is our St. George, and

that this ancient poem may be our great, missing, national

epic. The protagonist’s name is Beowulf, and I am the first poet

in almost a thousand years to read it. My Idylls of the King is now

complete, and I must admit that I have borrowed from my wildest

imaginings, as I am certain you have. Congratulations on your

new book. Sincerely, T.

Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, wrote back with two words as the body of his message:

Thank you. CD.

He added a postscript to the letter:

Strange but on my departure from the place, I looked out the

window of the hansom. Even though it was raining heavily,

I saw an enormous white rabbit hurrying along beside me,

perhaps racing my rig to see who would arrive first at my desk

– he or I. I tipped my hat to the aforesaid white Oryctolagus

cuniculus, and he appeared to stop and wave me on in a most

honorable salute. Please treasure our correspondence for the

length of time it would take to fall down a rabbit hole and then

put the matter to the dragon’s breath.

That is the story that has emerged from considerable scholarship. Neither Tennyson nor Lewis Carroll destroyed their correspondence, though both put a one-hundred-and-twenty-year embargo on the letters.

The story should end here with two well-known personages of a by-gone era winking at each other from the feathery hands of their elegant Victorian scripts, except for one small fact that recently came to light and, for the life of me, dear Reader, I cannot keep from you.

In January 2017, a rabbit hole was discovered on an estate in Shropshire (and this is a true story – I would not deceive you), that when entered revealed a large, long-forgotten Templar hideaway with chamber after chamber leading into the darkness of the deep below the tranquil landscape of the West Country. Amid the spiral pillars and the inexplicable delicacy of the vaulted ceilings – all hallmarks of the long-lost order of unlucky knights – some odd bones were found that are currently undergoing extensive testing at the Museum of Natural History in London. Among the debris of calcified remains were found the rusted skeleton of a Victorian umbrella, and a long, sword-like instrument with a brass plate affixed to a curved handle. The brass plate was cleaned so it could be read, and, on close inspection, the word ‘Vorpel’ emerged beneath the layers of tarnish.

Bruce Meyer is author of 68 books of poetry, short stories, flash fiction, and non-fiction. His stories have won or been shortlisted for numerous international awards, and his most recent collections of short fiction are Down in the Ground (Guernica Editions, 2020), The Hour (AOS Publishing, 2021), and Toast Soldiers (Crow's Nest Books, 2021).