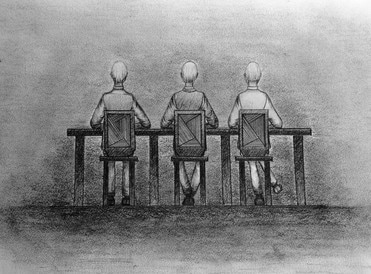

In the wide marble chamber, Heco, Cohe, and Oche sat at the large marble table near the rear door, each with the same stack of papers in front of him, each with a pen between his old fingers. Banks of fluorescent tubes beamed from overhead, illuminating the room in perfect uniformity.

Heco checked his watch, which, like the rest of his outfit, was red.

“It’s time,” he said, clearing his throat, which was as red as the suit jacket on his back, the red pants on his old, thin legs, the thickly soled red shoes on his arthritic feet.

“Who’s up first?” Cohe asked, sliding his white reading glasses over his nose, the pores of which were like craters of a pale moon. He brushed a nearly transparent hand through his wispy white hair, which matched perfectly the color of his suit, as white and spotless as newly fallen snow.

“It says here,” Oche said, clearing in turn his throat and peering at the list of names before him, “that it is one Mitchell Gladney.” Toward the other two men he turned his eyes, filmy orbs as blue as the tie he carefully knotted every morning, and just as carefully unknotted every night before easing himself into bed, whose covers were as blue as the veins that spread like cracks in milky glass along the pale lengths of his feeble calves.

Heco pressed a button on the desk. A woman’s voice came through a speaker overhead.

“Yes, Mr. Heco?”

“Ms. Mowan, please send in the first applicant.”

“Yes, Mr. Heco.”

The three men stared straight ahead toward the front of the room, facing a large blank white wall, without window or adornment. This, they had come to understand, gave them the best chance to review each candidate most clearly, without background interference or complications of context getting in the way.

There were two doors, one on each side wall, near the front of the room. On the left stood a door of mahogany, with a small rhombus of beautiful stained glass, green and yellow, at eye level. Arabesque designs had been carved into the richly stained reddish-brown wood. The ornate doorknob was brass with chips of multicolored glass surrounding it.

On the right stood a door of the same size, but pneumatic, and made entirely of steel. It was smooth and shone like a mirror. A steel knob protruded seamlessly from its surface.

The door on the right opened and in walked a middle-aged man, dressed in a navy blue suit, with a cornflower blue tie, upon which had been adorned a dazzling diamond tie clip. His dyed hair was auburn, his face a pale salmon color. The door closed behind him, and he walked exactly halfway across the front of the room, as if counting his steps, before stopping to face the men.

“Good morning,” Mitchell Gladney said, his voice like a trombone in a marching band.

“Good morning,” the three old men said, first Heco, then Cohe, then Oche.

Heco examined one of the papers in front of him. “It says here you’ve spent your life in finance. Is that right?”

“I would say it’s more correct than right,” Gladney said, making a point of looking at each of the doors, spreading his hands out at his sides as if measuring something.

Cohe raised an eyebrow and coughed. “And what makes you think you’d be right for the job?”

Mitchell smiled his winning smile. “I have spent years listening to various points of view, and consider myself very well-balanced, very well –”

Oche broke in. “So you’re a listener?” he said, with perhaps an air of suspicion creeping into his words. “Someone who looks at the bigger picture?”

Gladney gave him a knowing look and slowly shook his head.

“No, sir,” he said, “that’s not what I’m implying at all. I meant to say that I listen with both ears wide open, with equal attention to those voices with the most –how shall we say – persuasion.”

This last word came out slowly, as if it tasted too good to let it escape from his mouth, and as it did he glanced down at his sparkling tie clip.

The three old men nodded in unison, and a thin smile found its way onto Heco’s lined face.

“Thank you for your time,” the man in red said. “You will be notified soon whether you have been awarded the position.”

Mitchell Gladney bowed slightly, smiled once again, and walked through the opposite door from which he entered, closing it behind him.

“Well?” Cohe said, lifting his white reading glasses and rubbing the skin of his nose.

“I’m skeptical,” the man in blue said. “While he certainly looks the part, and clearly gets the importance of being persuaded, he sounds too willing to listen to just anyone.”

Heco nodded. “It’s one thing to be influenced by value, it’s quite another to allow the possibility of just anyone’s values.”

Cohe finished with his bony nose and again slipped on the bifocals. “But not a bad start, all things considered.”

“Let’s see who’s next,” Oche said, making a note with his blue pen.

Heco again pressed the button.

Ms. Mowan’s voice came through the speaker. “Send in the next applicant?”

“Yes, dear,” Heco said.

This time the door on the left opened and a man, dressed in blue jeans and a black button-up shirt, walked a step into the room before stopping. His complexion reminded one of cedar, and his eyes too were like two small cedar ponds. His hair was long, and it fell, cinnamon brown, upon his shoulders. He had a warm smile for the three men.

The men at the table glanced at each other. Cohe coughed.

“What’s your name?” Heco asked.

“Alejandro Harjo,” the young man said.

Cohe raised an eyebrow. “And how old are you, son?”

“I’m 39 years old.”

Oche marked something down. “Just old enough. And where are your parents from?”

Alejandro folded his hands in front of him. “Oklahoma.”

Oche looked at the other two men.

“I think what Oche wants to know,” Heco said, “is where your parents are from originally.”

Alejandro unfolded his hands and looked down at them. They were strong and capable, and he saw traces of his parents’ hands in them, and their parents’.

“My father was born in Okemah, and my mother was born in Oklahoma City.”

Cohe sighed, the air escaping in stages, rattling out through his ancient windpipe. “I’m sorry if this is confusing. We mean, where are your people from, originally?”

Alejandro nodded, felt the air entering and exiting his lungs, the steady beating of his heart. “For thousands of years previous to the coming of Europeans, my father’s people lived in what is now called the American Midwest. My mother’s mother was born in Monterrey.”

“California?” Oche said.

“Mexico,” the young man said.

“Ah,” Heco said. “Thank you very much for coming in, uh, Alexander. You will hear from us shortly about whether you have been given the job.”

“Thank you for your time,” Alejandro Harjo said. He reached for the brass knob, opened the exquisite mahogany door, and left.

As soon as the door closed Cohe put down his white pen and took off his white glasses. “I’ll be the first to say it. He was being evasive.”

Heco stopped scribbling with his red pen. “Nearly impossible to get a straight answer out of him.”

“And I think,” Oche added, “we can all agree that 39 is hardly old enough for a position this important.”

Heco again pressed the button, Ms. Mowan responded, and the three men had enough time to ruffle their papers before a woman of early middle-age walked through the door on the left. She was wearing a long yellow dress, and she had hair the color of a raven’s wings and skin the hue of wet beach sand. She walked from the door, and then stopped, about a third of the way into the room.

“Hello,” Cohe said. He squinted at the paper. “Mrs. Li, we presume?”

“Julian Li,” the woman said.

Oche peered at her. “Not married?”

Julian Li’s eyes narrowed a hundredth of an inch, perhaps due to the bright fluorescence. “I am married.”

Heco ran a scrawny finger absentmindedly across the rim of the button on the desk. “Any children?”

Li looked at the old man. “I have no children.”

Cohe furrowed his brow. “You mean they are grown?”

Her voice was soft and resonant, like a clarinet. “No, I mean I have no children.”

Oche looked at the paper in front of him. “Thank you, Mrs. Li. We will be letting applicants know shortly about the results.”

She paused for a moment, perhaps considering to speak, and then walked the few steps toward the door she had entered, and again the three men were by themselves.

“Opinionated,” Heco said, after a brief moment of quiet.

“Career seems quite important to her,” Cohe said, crossing out her name with his pen.

Oche closed his eyes. “There appeared to be some confusion about the order of things,” he said.

Heco took a sip from his red coffee mug, the ceramic shaking lightly between his trembling fingers. “In agreement as usual, gentlemen.” He placed the mug back onto the desk and pressed the button. Again the voice of Ms. Mowan, the rustling of paper upon the desk.

And through the steel door on the right came a woman of late middle-age wearing a beige suit and a string of pearls. Her skin was the shade of old newspaper, her hair dyed blonde, her eyes cobalt blue, her lips painted ruby. Cohe emitted what could have been a groan when the woman smoothed the pleats of her pants and walked slowly toward the center, then back toward the door through which she came.

“Good morning,” she said, her voice like glacial ice breaking apart in the arctic.

“Good morning,” the men said in unison. Cohe leaned forward in his chair, his bones creaking with the effort.

“Mrs. Goodwin?” Cohe said, moistening his lips.

“That’s right. It’s a pleasure to be here with you today.”

Cohe’s mouth was forming a word but Oche beat him to it. “The pleasure is all ours, we are sure.”

Patricia Goodwin smiled, the corners of her mouth pulled back as if with strings, revealing a row of even white teeth.

Heco examined his papers. “Your track record is, as it were, without blemish. The names of these contacts, very remarkable indeed. How do you account for such a flawless string of success?”

Goodwin ran her fingers lightly over her pearls, took another step toward the right, and then stopped. She glanced at the door on the left. “My primary concern is the good of everyone. So long as I focus on the well-being of others” – again she glanced at the mahogany door – “success is guaranteed.”

Cohe grunted in approval. “And your, um, children must be very proud of you?”

She smiled again, the fluorescent lighting glinting off her perfect teeth.

“Our lovely daughter works with my husband and myself at our foundation. And her husband is a banker.”

Oche marked something with his blue pen. “This is the sort of job that most people think requires conflict-resolution. What do you say about that?”

Patricia Goodwin’s eyes flashed and she lowered them, as if thinking. She slowly walked from right to left, the heels of her shiny leather shoes clacking smartly on the marble floor. She came to a stop in front of the other wall, and for a moment she examined the stained glass in the wooden door, running her gaze over the delicate multicolored glass shards decorating the brass knob. Then, her eyes still lowered as if in contemplation, she recrossed the room and leaned against the steel door. Her posture was cool, relaxed, yet still powerful. Heco and Oche glanced at Cohe, whose eyelids had apparently ceased to work.

“Conflict-resolution is, I suppose, fine in a pinch,” she began, the red of her nail polish a striking contrast against the gleaming opalescence of the pearls dangling elegantly upon the warm beige of her suit. “But who is to say that conflict itself isn’t more productive? After all, isn’t innovation born of competition? Isn’t war more a time of prosperity than peace? I certainly wouldn’t be standing here in front of you fine men” – she winked at Cohe, who coughed into his fist – “if it weren’t for the great war effort some generations ago.”

She paused, running her fingers from the pearls to the door behind her, letting them softly encircle the steel knob. The three men leaned forward. The pen shook in Cohe’s hand. Patricia Goodwin traced the perimeter of the doorknob like a sculptor molding clay.

“I understand the need for negotiation,” she said, her left eyebrow rising slightly. “If one does not have sufficient force.” Her hand fully enveloped the shiny knob, and then she let her fingers slowly release from the cold of the metal, the scarlet fingernails like tiny flecks of fire trailing lightly into the air. She stared unblinkingly at the men as a hawk might focus on three blind mice.

Cohe’s breathing was audible. “And you feel you have sufficient, um—”

Patricia stared directly at the old man. “I have more than sufficient everything. But I want to make one thing very clear.” She paused again, and when next she spoke her voice had taken on a melodic quality. “Equality is a pretty word I like to play with,” she breathed, her cadence a spell, “only in the presence of polite society.”

The three men were scribbling, the paper-thin skin of their fingers stretched tightly around their pens. Patricia Goodwin walked casually across their view, the practiced measure of her gait pressurizing the room. Their pens finally stopped moving and they looked up at her, the expectant silence in the room so loud that Cohe unthinkingly reached to turn down his hearing aid.

Mrs. Goodwin had returned to her original spot, just a step from the steel door she had entered. Her hands rested comfortably by her sides; the men could have stared for eternity at the polished gracefulness of her powerful demeanor. It was finally Heco who roused himself to speak.

“Well, Mrs. Goodwin. Patricia. May we call you that?”

“You may.”

“Patricia. I think I can speak for my two colleagues when I say that you have impressed us greatly.”

The other two men smiled and nodded vigorously. Cohe was still holding his pen, a large spot of ink developing where it lingered on the page.

“The feeling is mutual,” she said.

Oche smoothed his blue tie. “Unfortunately we can’t offer you the job until we’ve seen the remaining applicants.”

“I understand.” Her fingers once again traced the loop of her pearls.

“But we will most certainly be in touch,” Heco said.

“I certainly expect so,” she said. Gracefully, magnificently, she turned for the steel door, opened it, and before leaving stole one more look at the wooden door. With a final glance at the three men, letting her eyes fall lastly upon Cohe, whose grip had tightened even more on his pen, she exited the room.

The three men were silent a long time.

“Now that’s a woman,” Oche said at last. “Cohe certainly thought so, didn’t you?”

Cohe coughed. “What? Yes. Very well qualified. Very well balanced. I’m with her.”

“It feels rather superfluous at this point,” Heco said. “But we should, I suppose, screen all of the applicants before making a decision.”

“Before formalizing our decision,” Oche corrected.

“Right,” Cohe said, wiping sweat from the nose pads of his bifocals.

Heco pressed the button, Ms. Mowan’s pleasant voice briefly entered the room, and a moment later the door on the left opened. In stepped a woman with skin the hue of chestnut, hair like thick onyx foliage, irises like acorns still on the branch. She was wearing a shirt the color of ivy and a long russet skirt made of corduroy. A delicate brooch in the likeness of a goldfinch rested upon the fabric that traced her left clavicle. She was not wearing shoes. Gently she closed the door and stood next to it, never once looking at the door on the right, smiling warmly at the nearly agape men.

They stared. She stood like an oak in the prime of her life, the wind of their gazes passing harmlessly around her trunk, their scrutiny slipping innocuously through the sturdiness of her branches. She waited patiently for them, as if expecting this.

“Hello,” she said at last. “My name is Morrow.” The notes of her words fell and then danced lightly upon the air, reverberating softly against the marble walls like the music of a songbird faintly foreshadowing the arrival of a long-awaited dawn.

“Hello,” the three men muttered, though that was all they could say at the moment. They were alternating their glances between her and their files– mostly between her bare feet and their files. At last Oche seemed to find something.

“All of your experience,” he said as evenly as he could, “seems to be based in organizations I have never heard of.”

“Nor I,” Heco said.

Cohe remained with his head down, pen in hand, his mind perhaps still upon tiny rectangles of red glittering atop small opaline balls.

“May I speak in metaphor?” the woman asked.

Heco frowned. “Metaphor?”

Oche, who considered himself somewhat literary, felt a part of his heart warm to this anomalous creature before him. “Humor us,” he said.

Morrow stood easily before them, her guileless gaze like a caressing stream running over the rocks of their beings.

“I am of the grass,” she said. “I am soil that teems with life; I am the tender crops that emerge fragile and pure in the spring. From heavy clouds I am summer rain that kisses thirsty roots; I am the sickle of autumn that guides earthen grains into woven baskets. But who I am is not important; it is what I am that matters. What blows through me, and guides me, and speaks through this chest, this mouth, this body – all of which It borrows for a brief time, before moving on to somewhere else.”

She paused, the brown of her eyes alight with their own bright gleaming, almost like candlelight, whose gentle radiance effortlessly repelled the fluorescence above.

Oche politely cleared his throat. “While I appreciate the depth of your lyricism, perhaps for the sake of my colleagues it might be best to speak in plainer terms.”

She smiled. “As you wish.”

Heco looked at Oche, then back at the disturbance before them. “What exactly would you bring to this job?” the man in red asked.

“I would bring only honesty, even in the most challenging moments. Truth would be my sole source of inspiration. Virtue would write my speeches; integrity would lead my words and deeds. My voice would simply be the messenger for that which needs body to find utterance.”

Oche raised his hand slowly from the table. “Please, your language is still rather—”

“Vague,” Cohe said, apparently broken enough out of his spell to finally consider the interruption now before them. “Is there anything you can tell us of substance?”

Oche nodded, and Heco began listlessly running his finger around the lip of the button.

Morrow closed her eyes and began to sing. Like hundreds of radiant butterflies released at once from the cocoon of her soul, the shimmering notes of her melody glimmered and glided into every corner of that chamber, rising and diving, gaining strength and falling away, the echoes of the dying words interlacing with those newly born:

This earth, I know to be home,

and I know you to be of this house;

I welcome all things that are here,

for all that is, is holy.

In love we find our voice

in magic we sing and dance

in spirit we find our place

as One, we have a chance.

When she finished she opened her eyes, which were wet. Heco was staring at her feet, his finger now running nervously atop the button. Cohe had returned to his notes on Mrs. Goodwin, and his hand had once again gripped his white pen tightly. Oche was picking a piece of lint from his blue pants, and looked up when the last of the echoes had finally faded.

“Very nice, Ms. Morrow,” Heco said. “We’re still interviewing, and we’ll let everyone know shortly whether they’ve been selected for the position.”

Morrow bowed her head slightly and smiled. With a look mixed equally of sadness and hope, she waved goodbye, turned the brass knob, and slipped from view. The door closed nearly inaudibly behind her.

Then, all at once, the three old men began to laugh, slowly at first, quietly, but gaining force, until the room was filled with the sound of their reverberating guffaws, their withered frames shaking with mirth.

“That was rich,” Cohe said when he had finally regained composure.

“Perhaps our secretary played a little joke on us,” the man in blue said.

Heco pressed the button.

“Yes, Mr. Heco?”

“Ms. Mowan,” the man in red said. “Was that an attempt at humor? Because if so, well done. Very well done.”

“I assure you,” she said, a note of unease in her voice, “all of these applicants are here for a reason.”

Heco shrugged. “If you say so. Are there any more remaining?”

“One more. Can I please send him in?”

“Of course,” he said.

After a minute the steel door opened slightly, but no one yet emerged. The three old men could hear the voice of a man, as well as the voice of their secretary. They could not discern what was being said, but soon they heard loud laughter from the man, and then the door opened wide, revealing the last of their candidates.

He was a tall man in late middle-age, with skin like a rotting peach and dyed hair the color of long-spoiled milk. His suit was blue, his tie red, his shirt a snowy white. He held the steel door open and took from his breast pocket his wallet, which he tried unsuccessfully to stuff under the door to prop it open. He smiled at the three men, opened the wallet, removed a massive wad of bills, and then again tried to slide the wallet under the door. It was still too thick. He thought for a moment, and then peeled a number of bills from the thick stack. He folded them in half and slipped them under the door, which slid a couple inches before coming to a stop.

He nodded, and rested his hand on the steel knob.

“Morning, gentlemen,” the man said. “Hope you don’t mind, I’d like to keep admiring the view while I speak with you.” As he said this he looked back into the other room, taking a long moment before turning again to the three men.

“It is highly unusual,” Heco said.

The man in front of the room blinked. As if remembering something, he looked down and saw he was still holding his money.

“They say this stuff can open a lot of doors,” he said, gently caressing the bills before placing them tenderly back into his wallet, which he slid with a deft movement into the breast pocket over his heart.

There was a silence, and then Cohe let out what sounded like something between a cough and a laugh. “Ah, a good joke, Mr.—”

“Richard Magnus,” he said, glancing again through the open door. “I must say, you have a fantastic decoration in your waiting room.”

“Thank you, Mr. Magnus,” Oche said. “Though that’s all Ms. Mowan’s doing.”

Richard Magnus winked. “You couldn’t be more right.”

“Well,” Heco said. “Shall we get down to business?”

“Business?” Magnus said. “Glad you asked. Business is my business.”

The old men took a moment to examine their files. While waiting for them, Richard Magnus alternated glances between the waiting room and the steel door, where his reflection gleamed. He adjusted his red tie, smoothing it along the length of his immaculate white shirt.

Heco looked up from the paper he had been reading, an eyebrow raised. “Are these figures accurate?”

Richard Magnus pealed his eyes from the door and looked at Heco. “I can’t say for sure. Depends how large they are.”

Oche let out a chuckle. “They are very large indeed. How exactly do you define success, Mr. Magnus?”

“I’m going to tell you a story,” the man said, his voice like a steel girder falling from a crane and landing on a group of people far below. “I was on the roof of my tower the other day, some quarter mile up, and as the wind blew through my hair, I peered down at the streets. And I saw the most wonderful thing there is to see. Humanity. But miniaturized, so small that it was like I was looking at an animated train set. All of them in the shadow of the building bearing my name.”

“Impressive,” Heco said, making a brief note with his red pen.

“Extremely impressive,” Oche agreed, circling one of the numbers with his blue pen.

Cohe had been doodling on Patricia Goodwin’s files, but he put them aside and began to peruse Mr. Magnus’s records. After a moment he said, “And how did you rise to such heights?”

Richard nodded at this question, one he had certainly been asked countless times before. “How do any of us achieve real success? How did you men get to sit in those chairs in this room? Understanding how the system works. That’s how.” He paused for a moment, glancing into the adjoining room before leveling his gaze upon the old men.

“Let me tell you another story. When I was a kid, my brothers and sisters and I would play a game to see who was best at hiding and finding pennies. The rule was this: they had to be put somewhere in the house, with the only place off limits our parents’ room. We would mark each of the pennies with a piece of tape with our initial on it to show who they belonged to. After we hid them, we would search for each other’s pennies. Those that we found, we got to keep. I’d often find many belonging to my brothers and sisters, even though I was the fourth youngest and their hiding places were clever. But they never found any with my initial on it.”

“And why is that?” asked Heco, who was jotting down notes while Magnus told his story.

“Because my hiding place was better.”

“Did you place them in your parents’ room?” Cohe asked.

“Or outside?” Oche suggested.

Richard Magnus shook his head. “I am not a cheater, gentlemen. I followed the rules the whole time.”

The three men sat frustrated, each wanting to guess where the young Richard had hidden his pennies.

“Give up?” Magnus asked at last.

They nodded. “I’m afraid we do,” Heco said. “Where did you hide your pennies?”

Richard Magnus grinned, snuck a glance at himself in the steel door, and then gently patted his stomach. “I swallowed them.”

The men were taken aback. Heco raised a hand to his mouth, running a finger around his lips. “Wasn’t that dangerous?”

Magnus shook his head. “I coated them in Vaseline, and swallowed them one at a time. They would just slide right down my throat.”

Cohe’s brow furrowed. “But then, how did you--?”

Magnus nodded. “A couple days later they would come out. Sometimes it hurt a little, but it was worth it. And they were easy to spot. I’d just fish them out, rinse them off, and add them to my collection. To this day, my brothers and sisters still think I cheated. But I simply outsmarted them.”

The men were speechless for a long moment. Then, Oche put his hands up and clapped them softly together.

“What resourcefulness for someone so young,” Oche said.

Heco nodded. “Bravo, sir.”

Cohe was busy scribbling, and then stopped to look up. “So, it’s loopholes then? That’s your secret?”

Richard Magnus glanced again into the waiting room, smiled in that direction, and then refocused on the men.

“My success is based on being smarter than those around me. That’s it.”

The men were leaning forward in their chairs now. Their earlier certainty regarding Patricia Goodwin had dissolved, even Cohe’s, and they looked with fascination at the man before them.

“What do you stand for?” Heco asked.

Magnus looked startled. “Stand for?”

Cohe glanced at Heco. “What are your principles?” the man in white clarified.

“Principles?” the man said, perplexed.

“Yes,” the man in blue said. “What guides your business practices? Why do you do what you do? What motivates you?”

The light of recognition went on in Magnus’s eyes, though he still seemed a bit confused.

“I don’t want to sound rude, gentlemen, but those two stories, of the tower and the pennies, are the only ones I brought.”

Heco stared at him for a moment, and then he seemed to understand. “You are not a rule breaker, are you Mr. Magnus?”

“You’re exactly right,” Richard said. “I simply try to work well within the rules. And if that doesn’t work, I find ways to change them for my benefit.”

Cohe too appeared to recognize the gift that had been laid before them. “You’ll say whatever it takes, won’t you Mr. Magnus?”

“I’ve never understood why people attach so much importance to words,” the man agreed.

“Mr. Magnus,” Oche said. “How do you think the system is working?”

Magnus beamed at the man. “It always makes me laugh when I hear people say how broken the system is. It’s only broken for those who aren’t smart enough to work within it. As you gentlemen know quite well, the system is working just fine.”

Under the revelatory glow of the fluorescents above them, the three old men finally understood. They slowly swiveled their necks and met each other’s eyes and smiled. They had found their man.

Heco looked down at his watch. “Well, Mr. Magnus. You’re the last candidate of the day. We thought earlier that we had found the right fit, but we were mistaken. Weren’t we, gentlemen?”

“Oh yes,” Oche said. He had written down the last words Magnus had uttered, and was underlining them with his pen.

With one last lingering glance at Patricia Goodwin’s file, Cohe too nodded, his bald dome with scant white hair shining beneath the lights. “Mr. Magnus, you have left us no doubt. No doubt at all.”

“So that’s it?” Richard Magnus asked.

“That’s it,” Heco said.

Magnus nodded and knelt to collect the money from beneath the door. He smiled again into the waiting room before letting the steel door slowly close shut. Then he smoothly unfolded the bills, took out his wallet and slipped them inside, tenderly placing the thick leather object back into his breast pocket. With long strides he approached the men at their desk and shook each of their feeble hands in turn. After doing so, he turned to go.

“Oh, Mr. Magnus,” Heco said, easing himself gingerly from his chair. “You can leave with us, through here.” He motioned behind himself to a door, a flimsy piece of particle board slathered a dark brown.

“That’s right,” Cohe said, pushing himself up to a standing position. “You’re with us, now.”

Oche gradually got up and patted Magnus on the arm. “How does lunch sound?” the old man said.

“It sounds great,” the newly hired man said.

Heco grabbed his red cane, slowly moved to the door and opened it. The old man in red went through, followed by the man in white and the man in blue. Richard Magnus, bringing up the rear in his red tie, white shirt and blue suit, followed them through, pausing for a moment to see if he could find a trace of his reflection in the thick chunky dark brown paint. He could, and he smiled. Then he too passed out of sight through the back door.

Heco checked his watch, which, like the rest of his outfit, was red.

“It’s time,” he said, clearing his throat, which was as red as the suit jacket on his back, the red pants on his old, thin legs, the thickly soled red shoes on his arthritic feet.

“Who’s up first?” Cohe asked, sliding his white reading glasses over his nose, the pores of which were like craters of a pale moon. He brushed a nearly transparent hand through his wispy white hair, which matched perfectly the color of his suit, as white and spotless as newly fallen snow.

“It says here,” Oche said, clearing in turn his throat and peering at the list of names before him, “that it is one Mitchell Gladney.” Toward the other two men he turned his eyes, filmy orbs as blue as the tie he carefully knotted every morning, and just as carefully unknotted every night before easing himself into bed, whose covers were as blue as the veins that spread like cracks in milky glass along the pale lengths of his feeble calves.

Heco pressed a button on the desk. A woman’s voice came through a speaker overhead.

“Yes, Mr. Heco?”

“Ms. Mowan, please send in the first applicant.”

“Yes, Mr. Heco.”

The three men stared straight ahead toward the front of the room, facing a large blank white wall, without window or adornment. This, they had come to understand, gave them the best chance to review each candidate most clearly, without background interference or complications of context getting in the way.

There were two doors, one on each side wall, near the front of the room. On the left stood a door of mahogany, with a small rhombus of beautiful stained glass, green and yellow, at eye level. Arabesque designs had been carved into the richly stained reddish-brown wood. The ornate doorknob was brass with chips of multicolored glass surrounding it.

On the right stood a door of the same size, but pneumatic, and made entirely of steel. It was smooth and shone like a mirror. A steel knob protruded seamlessly from its surface.

The door on the right opened and in walked a middle-aged man, dressed in a navy blue suit, with a cornflower blue tie, upon which had been adorned a dazzling diamond tie clip. His dyed hair was auburn, his face a pale salmon color. The door closed behind him, and he walked exactly halfway across the front of the room, as if counting his steps, before stopping to face the men.

“Good morning,” Mitchell Gladney said, his voice like a trombone in a marching band.

“Good morning,” the three old men said, first Heco, then Cohe, then Oche.

Heco examined one of the papers in front of him. “It says here you’ve spent your life in finance. Is that right?”

“I would say it’s more correct than right,” Gladney said, making a point of looking at each of the doors, spreading his hands out at his sides as if measuring something.

Cohe raised an eyebrow and coughed. “And what makes you think you’d be right for the job?”

Mitchell smiled his winning smile. “I have spent years listening to various points of view, and consider myself very well-balanced, very well –”

Oche broke in. “So you’re a listener?” he said, with perhaps an air of suspicion creeping into his words. “Someone who looks at the bigger picture?”

Gladney gave him a knowing look and slowly shook his head.

“No, sir,” he said, “that’s not what I’m implying at all. I meant to say that I listen with both ears wide open, with equal attention to those voices with the most –how shall we say – persuasion.”

This last word came out slowly, as if it tasted too good to let it escape from his mouth, and as it did he glanced down at his sparkling tie clip.

The three old men nodded in unison, and a thin smile found its way onto Heco’s lined face.

“Thank you for your time,” the man in red said. “You will be notified soon whether you have been awarded the position.”

Mitchell Gladney bowed slightly, smiled once again, and walked through the opposite door from which he entered, closing it behind him.

“Well?” Cohe said, lifting his white reading glasses and rubbing the skin of his nose.

“I’m skeptical,” the man in blue said. “While he certainly looks the part, and clearly gets the importance of being persuaded, he sounds too willing to listen to just anyone.”

Heco nodded. “It’s one thing to be influenced by value, it’s quite another to allow the possibility of just anyone’s values.”

Cohe finished with his bony nose and again slipped on the bifocals. “But not a bad start, all things considered.”

“Let’s see who’s next,” Oche said, making a note with his blue pen.

Heco again pressed the button.

Ms. Mowan’s voice came through the speaker. “Send in the next applicant?”

“Yes, dear,” Heco said.

This time the door on the left opened and a man, dressed in blue jeans and a black button-up shirt, walked a step into the room before stopping. His complexion reminded one of cedar, and his eyes too were like two small cedar ponds. His hair was long, and it fell, cinnamon brown, upon his shoulders. He had a warm smile for the three men.

The men at the table glanced at each other. Cohe coughed.

“What’s your name?” Heco asked.

“Alejandro Harjo,” the young man said.

Cohe raised an eyebrow. “And how old are you, son?”

“I’m 39 years old.”

Oche marked something down. “Just old enough. And where are your parents from?”

Alejandro folded his hands in front of him. “Oklahoma.”

Oche looked at the other two men.

“I think what Oche wants to know,” Heco said, “is where your parents are from originally.”

Alejandro unfolded his hands and looked down at them. They were strong and capable, and he saw traces of his parents’ hands in them, and their parents’.

“My father was born in Okemah, and my mother was born in Oklahoma City.”

Cohe sighed, the air escaping in stages, rattling out through his ancient windpipe. “I’m sorry if this is confusing. We mean, where are your people from, originally?”

Alejandro nodded, felt the air entering and exiting his lungs, the steady beating of his heart. “For thousands of years previous to the coming of Europeans, my father’s people lived in what is now called the American Midwest. My mother’s mother was born in Monterrey.”

“California?” Oche said.

“Mexico,” the young man said.

“Ah,” Heco said. “Thank you very much for coming in, uh, Alexander. You will hear from us shortly about whether you have been given the job.”

“Thank you for your time,” Alejandro Harjo said. He reached for the brass knob, opened the exquisite mahogany door, and left.

As soon as the door closed Cohe put down his white pen and took off his white glasses. “I’ll be the first to say it. He was being evasive.”

Heco stopped scribbling with his red pen. “Nearly impossible to get a straight answer out of him.”

“And I think,” Oche added, “we can all agree that 39 is hardly old enough for a position this important.”

Heco again pressed the button, Ms. Mowan responded, and the three men had enough time to ruffle their papers before a woman of early middle-age walked through the door on the left. She was wearing a long yellow dress, and she had hair the color of a raven’s wings and skin the hue of wet beach sand. She walked from the door, and then stopped, about a third of the way into the room.

“Hello,” Cohe said. He squinted at the paper. “Mrs. Li, we presume?”

“Julian Li,” the woman said.

Oche peered at her. “Not married?”

Julian Li’s eyes narrowed a hundredth of an inch, perhaps due to the bright fluorescence. “I am married.”

Heco ran a scrawny finger absentmindedly across the rim of the button on the desk. “Any children?”

Li looked at the old man. “I have no children.”

Cohe furrowed his brow. “You mean they are grown?”

Her voice was soft and resonant, like a clarinet. “No, I mean I have no children.”

Oche looked at the paper in front of him. “Thank you, Mrs. Li. We will be letting applicants know shortly about the results.”

She paused for a moment, perhaps considering to speak, and then walked the few steps toward the door she had entered, and again the three men were by themselves.

“Opinionated,” Heco said, after a brief moment of quiet.

“Career seems quite important to her,” Cohe said, crossing out her name with his pen.

Oche closed his eyes. “There appeared to be some confusion about the order of things,” he said.

Heco took a sip from his red coffee mug, the ceramic shaking lightly between his trembling fingers. “In agreement as usual, gentlemen.” He placed the mug back onto the desk and pressed the button. Again the voice of Ms. Mowan, the rustling of paper upon the desk.

And through the steel door on the right came a woman of late middle-age wearing a beige suit and a string of pearls. Her skin was the shade of old newspaper, her hair dyed blonde, her eyes cobalt blue, her lips painted ruby. Cohe emitted what could have been a groan when the woman smoothed the pleats of her pants and walked slowly toward the center, then back toward the door through which she came.

“Good morning,” she said, her voice like glacial ice breaking apart in the arctic.

“Good morning,” the men said in unison. Cohe leaned forward in his chair, his bones creaking with the effort.

“Mrs. Goodwin?” Cohe said, moistening his lips.

“That’s right. It’s a pleasure to be here with you today.”

Cohe’s mouth was forming a word but Oche beat him to it. “The pleasure is all ours, we are sure.”

Patricia Goodwin smiled, the corners of her mouth pulled back as if with strings, revealing a row of even white teeth.

Heco examined his papers. “Your track record is, as it were, without blemish. The names of these contacts, very remarkable indeed. How do you account for such a flawless string of success?”

Goodwin ran her fingers lightly over her pearls, took another step toward the right, and then stopped. She glanced at the door on the left. “My primary concern is the good of everyone. So long as I focus on the well-being of others” – again she glanced at the mahogany door – “success is guaranteed.”

Cohe grunted in approval. “And your, um, children must be very proud of you?”

She smiled again, the fluorescent lighting glinting off her perfect teeth.

“Our lovely daughter works with my husband and myself at our foundation. And her husband is a banker.”

Oche marked something with his blue pen. “This is the sort of job that most people think requires conflict-resolution. What do you say about that?”

Patricia Goodwin’s eyes flashed and she lowered them, as if thinking. She slowly walked from right to left, the heels of her shiny leather shoes clacking smartly on the marble floor. She came to a stop in front of the other wall, and for a moment she examined the stained glass in the wooden door, running her gaze over the delicate multicolored glass shards decorating the brass knob. Then, her eyes still lowered as if in contemplation, she recrossed the room and leaned against the steel door. Her posture was cool, relaxed, yet still powerful. Heco and Oche glanced at Cohe, whose eyelids had apparently ceased to work.

“Conflict-resolution is, I suppose, fine in a pinch,” she began, the red of her nail polish a striking contrast against the gleaming opalescence of the pearls dangling elegantly upon the warm beige of her suit. “But who is to say that conflict itself isn’t more productive? After all, isn’t innovation born of competition? Isn’t war more a time of prosperity than peace? I certainly wouldn’t be standing here in front of you fine men” – she winked at Cohe, who coughed into his fist – “if it weren’t for the great war effort some generations ago.”

She paused, running her fingers from the pearls to the door behind her, letting them softly encircle the steel knob. The three men leaned forward. The pen shook in Cohe’s hand. Patricia Goodwin traced the perimeter of the doorknob like a sculptor molding clay.

“I understand the need for negotiation,” she said, her left eyebrow rising slightly. “If one does not have sufficient force.” Her hand fully enveloped the shiny knob, and then she let her fingers slowly release from the cold of the metal, the scarlet fingernails like tiny flecks of fire trailing lightly into the air. She stared unblinkingly at the men as a hawk might focus on three blind mice.

Cohe’s breathing was audible. “And you feel you have sufficient, um—”

Patricia stared directly at the old man. “I have more than sufficient everything. But I want to make one thing very clear.” She paused again, and when next she spoke her voice had taken on a melodic quality. “Equality is a pretty word I like to play with,” she breathed, her cadence a spell, “only in the presence of polite society.”

The three men were scribbling, the paper-thin skin of their fingers stretched tightly around their pens. Patricia Goodwin walked casually across their view, the practiced measure of her gait pressurizing the room. Their pens finally stopped moving and they looked up at her, the expectant silence in the room so loud that Cohe unthinkingly reached to turn down his hearing aid.

Mrs. Goodwin had returned to her original spot, just a step from the steel door she had entered. Her hands rested comfortably by her sides; the men could have stared for eternity at the polished gracefulness of her powerful demeanor. It was finally Heco who roused himself to speak.

“Well, Mrs. Goodwin. Patricia. May we call you that?”

“You may.”

“Patricia. I think I can speak for my two colleagues when I say that you have impressed us greatly.”

The other two men smiled and nodded vigorously. Cohe was still holding his pen, a large spot of ink developing where it lingered on the page.

“The feeling is mutual,” she said.

Oche smoothed his blue tie. “Unfortunately we can’t offer you the job until we’ve seen the remaining applicants.”

“I understand.” Her fingers once again traced the loop of her pearls.

“But we will most certainly be in touch,” Heco said.

“I certainly expect so,” she said. Gracefully, magnificently, she turned for the steel door, opened it, and before leaving stole one more look at the wooden door. With a final glance at the three men, letting her eyes fall lastly upon Cohe, whose grip had tightened even more on his pen, she exited the room.

The three men were silent a long time.

“Now that’s a woman,” Oche said at last. “Cohe certainly thought so, didn’t you?”

Cohe coughed. “What? Yes. Very well qualified. Very well balanced. I’m with her.”

“It feels rather superfluous at this point,” Heco said. “But we should, I suppose, screen all of the applicants before making a decision.”

“Before formalizing our decision,” Oche corrected.

“Right,” Cohe said, wiping sweat from the nose pads of his bifocals.

Heco pressed the button, Ms. Mowan’s pleasant voice briefly entered the room, and a moment later the door on the left opened. In stepped a woman with skin the hue of chestnut, hair like thick onyx foliage, irises like acorns still on the branch. She was wearing a shirt the color of ivy and a long russet skirt made of corduroy. A delicate brooch in the likeness of a goldfinch rested upon the fabric that traced her left clavicle. She was not wearing shoes. Gently she closed the door and stood next to it, never once looking at the door on the right, smiling warmly at the nearly agape men.

They stared. She stood like an oak in the prime of her life, the wind of their gazes passing harmlessly around her trunk, their scrutiny slipping innocuously through the sturdiness of her branches. She waited patiently for them, as if expecting this.

“Hello,” she said at last. “My name is Morrow.” The notes of her words fell and then danced lightly upon the air, reverberating softly against the marble walls like the music of a songbird faintly foreshadowing the arrival of a long-awaited dawn.

“Hello,” the three men muttered, though that was all they could say at the moment. They were alternating their glances between her and their files– mostly between her bare feet and their files. At last Oche seemed to find something.

“All of your experience,” he said as evenly as he could, “seems to be based in organizations I have never heard of.”

“Nor I,” Heco said.

Cohe remained with his head down, pen in hand, his mind perhaps still upon tiny rectangles of red glittering atop small opaline balls.

“May I speak in metaphor?” the woman asked.

Heco frowned. “Metaphor?”

Oche, who considered himself somewhat literary, felt a part of his heart warm to this anomalous creature before him. “Humor us,” he said.

Morrow stood easily before them, her guileless gaze like a caressing stream running over the rocks of their beings.

“I am of the grass,” she said. “I am soil that teems with life; I am the tender crops that emerge fragile and pure in the spring. From heavy clouds I am summer rain that kisses thirsty roots; I am the sickle of autumn that guides earthen grains into woven baskets. But who I am is not important; it is what I am that matters. What blows through me, and guides me, and speaks through this chest, this mouth, this body – all of which It borrows for a brief time, before moving on to somewhere else.”

She paused, the brown of her eyes alight with their own bright gleaming, almost like candlelight, whose gentle radiance effortlessly repelled the fluorescence above.

Oche politely cleared his throat. “While I appreciate the depth of your lyricism, perhaps for the sake of my colleagues it might be best to speak in plainer terms.”

She smiled. “As you wish.”

Heco looked at Oche, then back at the disturbance before them. “What exactly would you bring to this job?” the man in red asked.

“I would bring only honesty, even in the most challenging moments. Truth would be my sole source of inspiration. Virtue would write my speeches; integrity would lead my words and deeds. My voice would simply be the messenger for that which needs body to find utterance.”

Oche raised his hand slowly from the table. “Please, your language is still rather—”

“Vague,” Cohe said, apparently broken enough out of his spell to finally consider the interruption now before them. “Is there anything you can tell us of substance?”

Oche nodded, and Heco began listlessly running his finger around the lip of the button.

Morrow closed her eyes and began to sing. Like hundreds of radiant butterflies released at once from the cocoon of her soul, the shimmering notes of her melody glimmered and glided into every corner of that chamber, rising and diving, gaining strength and falling away, the echoes of the dying words interlacing with those newly born:

This earth, I know to be home,

and I know you to be of this house;

I welcome all things that are here,

for all that is, is holy.

In love we find our voice

in magic we sing and dance

in spirit we find our place

as One, we have a chance.

When she finished she opened her eyes, which were wet. Heco was staring at her feet, his finger now running nervously atop the button. Cohe had returned to his notes on Mrs. Goodwin, and his hand had once again gripped his white pen tightly. Oche was picking a piece of lint from his blue pants, and looked up when the last of the echoes had finally faded.

“Very nice, Ms. Morrow,” Heco said. “We’re still interviewing, and we’ll let everyone know shortly whether they’ve been selected for the position.”

Morrow bowed her head slightly and smiled. With a look mixed equally of sadness and hope, she waved goodbye, turned the brass knob, and slipped from view. The door closed nearly inaudibly behind her.

Then, all at once, the three old men began to laugh, slowly at first, quietly, but gaining force, until the room was filled with the sound of their reverberating guffaws, their withered frames shaking with mirth.

“That was rich,” Cohe said when he had finally regained composure.

“Perhaps our secretary played a little joke on us,” the man in blue said.

Heco pressed the button.

“Yes, Mr. Heco?”

“Ms. Mowan,” the man in red said. “Was that an attempt at humor? Because if so, well done. Very well done.”

“I assure you,” she said, a note of unease in her voice, “all of these applicants are here for a reason.”

Heco shrugged. “If you say so. Are there any more remaining?”

“One more. Can I please send him in?”

“Of course,” he said.

After a minute the steel door opened slightly, but no one yet emerged. The three old men could hear the voice of a man, as well as the voice of their secretary. They could not discern what was being said, but soon they heard loud laughter from the man, and then the door opened wide, revealing the last of their candidates.

He was a tall man in late middle-age, with skin like a rotting peach and dyed hair the color of long-spoiled milk. His suit was blue, his tie red, his shirt a snowy white. He held the steel door open and took from his breast pocket his wallet, which he tried unsuccessfully to stuff under the door to prop it open. He smiled at the three men, opened the wallet, removed a massive wad of bills, and then again tried to slide the wallet under the door. It was still too thick. He thought for a moment, and then peeled a number of bills from the thick stack. He folded them in half and slipped them under the door, which slid a couple inches before coming to a stop.

He nodded, and rested his hand on the steel knob.

“Morning, gentlemen,” the man said. “Hope you don’t mind, I’d like to keep admiring the view while I speak with you.” As he said this he looked back into the other room, taking a long moment before turning again to the three men.

“It is highly unusual,” Heco said.

The man in front of the room blinked. As if remembering something, he looked down and saw he was still holding his money.

“They say this stuff can open a lot of doors,” he said, gently caressing the bills before placing them tenderly back into his wallet, which he slid with a deft movement into the breast pocket over his heart.

There was a silence, and then Cohe let out what sounded like something between a cough and a laugh. “Ah, a good joke, Mr.—”

“Richard Magnus,” he said, glancing again through the open door. “I must say, you have a fantastic decoration in your waiting room.”

“Thank you, Mr. Magnus,” Oche said. “Though that’s all Ms. Mowan’s doing.”

Richard Magnus winked. “You couldn’t be more right.”

“Well,” Heco said. “Shall we get down to business?”

“Business?” Magnus said. “Glad you asked. Business is my business.”

The old men took a moment to examine their files. While waiting for them, Richard Magnus alternated glances between the waiting room and the steel door, where his reflection gleamed. He adjusted his red tie, smoothing it along the length of his immaculate white shirt.

Heco looked up from the paper he had been reading, an eyebrow raised. “Are these figures accurate?”

Richard Magnus pealed his eyes from the door and looked at Heco. “I can’t say for sure. Depends how large they are.”

Oche let out a chuckle. “They are very large indeed. How exactly do you define success, Mr. Magnus?”

“I’m going to tell you a story,” the man said, his voice like a steel girder falling from a crane and landing on a group of people far below. “I was on the roof of my tower the other day, some quarter mile up, and as the wind blew through my hair, I peered down at the streets. And I saw the most wonderful thing there is to see. Humanity. But miniaturized, so small that it was like I was looking at an animated train set. All of them in the shadow of the building bearing my name.”

“Impressive,” Heco said, making a brief note with his red pen.

“Extremely impressive,” Oche agreed, circling one of the numbers with his blue pen.

Cohe had been doodling on Patricia Goodwin’s files, but he put them aside and began to peruse Mr. Magnus’s records. After a moment he said, “And how did you rise to such heights?”

Richard nodded at this question, one he had certainly been asked countless times before. “How do any of us achieve real success? How did you men get to sit in those chairs in this room? Understanding how the system works. That’s how.” He paused for a moment, glancing into the adjoining room before leveling his gaze upon the old men.

“Let me tell you another story. When I was a kid, my brothers and sisters and I would play a game to see who was best at hiding and finding pennies. The rule was this: they had to be put somewhere in the house, with the only place off limits our parents’ room. We would mark each of the pennies with a piece of tape with our initial on it to show who they belonged to. After we hid them, we would search for each other’s pennies. Those that we found, we got to keep. I’d often find many belonging to my brothers and sisters, even though I was the fourth youngest and their hiding places were clever. But they never found any with my initial on it.”

“And why is that?” asked Heco, who was jotting down notes while Magnus told his story.

“Because my hiding place was better.”

“Did you place them in your parents’ room?” Cohe asked.

“Or outside?” Oche suggested.

Richard Magnus shook his head. “I am not a cheater, gentlemen. I followed the rules the whole time.”

The three men sat frustrated, each wanting to guess where the young Richard had hidden his pennies.

“Give up?” Magnus asked at last.

They nodded. “I’m afraid we do,” Heco said. “Where did you hide your pennies?”

Richard Magnus grinned, snuck a glance at himself in the steel door, and then gently patted his stomach. “I swallowed them.”

The men were taken aback. Heco raised a hand to his mouth, running a finger around his lips. “Wasn’t that dangerous?”

Magnus shook his head. “I coated them in Vaseline, and swallowed them one at a time. They would just slide right down my throat.”

Cohe’s brow furrowed. “But then, how did you--?”

Magnus nodded. “A couple days later they would come out. Sometimes it hurt a little, but it was worth it. And they were easy to spot. I’d just fish them out, rinse them off, and add them to my collection. To this day, my brothers and sisters still think I cheated. But I simply outsmarted them.”

The men were speechless for a long moment. Then, Oche put his hands up and clapped them softly together.

“What resourcefulness for someone so young,” Oche said.

Heco nodded. “Bravo, sir.”

Cohe was busy scribbling, and then stopped to look up. “So, it’s loopholes then? That’s your secret?”

Richard Magnus glanced again into the waiting room, smiled in that direction, and then refocused on the men.

“My success is based on being smarter than those around me. That’s it.”

The men were leaning forward in their chairs now. Their earlier certainty regarding Patricia Goodwin had dissolved, even Cohe’s, and they looked with fascination at the man before them.

“What do you stand for?” Heco asked.

Magnus looked startled. “Stand for?”

Cohe glanced at Heco. “What are your principles?” the man in white clarified.

“Principles?” the man said, perplexed.

“Yes,” the man in blue said. “What guides your business practices? Why do you do what you do? What motivates you?”

The light of recognition went on in Magnus’s eyes, though he still seemed a bit confused.

“I don’t want to sound rude, gentlemen, but those two stories, of the tower and the pennies, are the only ones I brought.”

Heco stared at him for a moment, and then he seemed to understand. “You are not a rule breaker, are you Mr. Magnus?”

“You’re exactly right,” Richard said. “I simply try to work well within the rules. And if that doesn’t work, I find ways to change them for my benefit.”

Cohe too appeared to recognize the gift that had been laid before them. “You’ll say whatever it takes, won’t you Mr. Magnus?”

“I’ve never understood why people attach so much importance to words,” the man agreed.

“Mr. Magnus,” Oche said. “How do you think the system is working?”

Magnus beamed at the man. “It always makes me laugh when I hear people say how broken the system is. It’s only broken for those who aren’t smart enough to work within it. As you gentlemen know quite well, the system is working just fine.”

Under the revelatory glow of the fluorescents above them, the three old men finally understood. They slowly swiveled their necks and met each other’s eyes and smiled. They had found their man.

Heco looked down at his watch. “Well, Mr. Magnus. You’re the last candidate of the day. We thought earlier that we had found the right fit, but we were mistaken. Weren’t we, gentlemen?”

“Oh yes,” Oche said. He had written down the last words Magnus had uttered, and was underlining them with his pen.

With one last lingering glance at Patricia Goodwin’s file, Cohe too nodded, his bald dome with scant white hair shining beneath the lights. “Mr. Magnus, you have left us no doubt. No doubt at all.”

“So that’s it?” Richard Magnus asked.

“That’s it,” Heco said.

Magnus nodded and knelt to collect the money from beneath the door. He smiled again into the waiting room before letting the steel door slowly close shut. Then he smoothly unfolded the bills, took out his wallet and slipped them inside, tenderly placing the thick leather object back into his breast pocket. With long strides he approached the men at their desk and shook each of their feeble hands in turn. After doing so, he turned to go.

“Oh, Mr. Magnus,” Heco said, easing himself gingerly from his chair. “You can leave with us, through here.” He motioned behind himself to a door, a flimsy piece of particle board slathered a dark brown.

“That’s right,” Cohe said, pushing himself up to a standing position. “You’re with us, now.”

Oche gradually got up and patted Magnus on the arm. “How does lunch sound?” the old man said.

“It sounds great,” the newly hired man said.

Heco grabbed his red cane, slowly moved to the door and opened it. The old man in red went through, followed by the man in white and the man in blue. Richard Magnus, bringing up the rear in his red tie, white shirt and blue suit, followed them through, pausing for a moment to see if he could find a trace of his reflection in the thick chunky dark brown paint. He could, and he smiled. Then he too passed out of sight through the back door.

Daniel Freeman is a writer and teacher deeply concerned with social and environmental justice.