Now these stories can be told better with strip drawings than with a story composed of sentences one after the other. […] It’s best for you to try on your own to imagine the series of cartoons with all the little figures of the characters in their places, against an effectively outlined background, but you must try at the same time not to imagine the figures, or the background either.

—Italo Calvino, “The Origin of the Birds”

—Italo Calvino, “The Origin of the Birds”

For the imagery of the classic modern physics thought experiments, picture an elevator floating in space, someone chasing a light beam, a bowling ball on a trampoline, a warping rubber mat, dots on a stretching balloon, or a spinning bucket in outer space—that would be a good start. Beside the light beam, for example, picture the running person skewed—stretched or squeezed, I forget which—according to the rules of the thought experiment (there are rules).

For the imagery of a thought experiment itself, picture a shared thought bubble between two thinking beings. Now, already this picture is a lie, and I mean this is in a stronger sense than all pictures are mental distortions, simplifications, cartoons. The shared thought bubble is a lie—isn’t it?—because thinking beings, as far as we know, never share the same picture in their minds’ eyes, only approximations based on descriptions.

Suppose I am right so far, and that the shared thought bubble representing a thought experiment is only a sketch of what happens when two thinking beings engage in this kind of physics. We have the cartoon of an idea, its contours only. (And it isn’t as if equations are not involved—this could be shown by drawing equations in thought bubbles—but we must remember that the equations we choose to represent physical phenomena depend on our underlying conceptual scheme, which comes back to pictures. (This, we can suppose, rules out the possibility of someone with aphantasia engaging in the physics of thought experiments, because we are exploring the space where visual—even fantastical—intuitions align.))

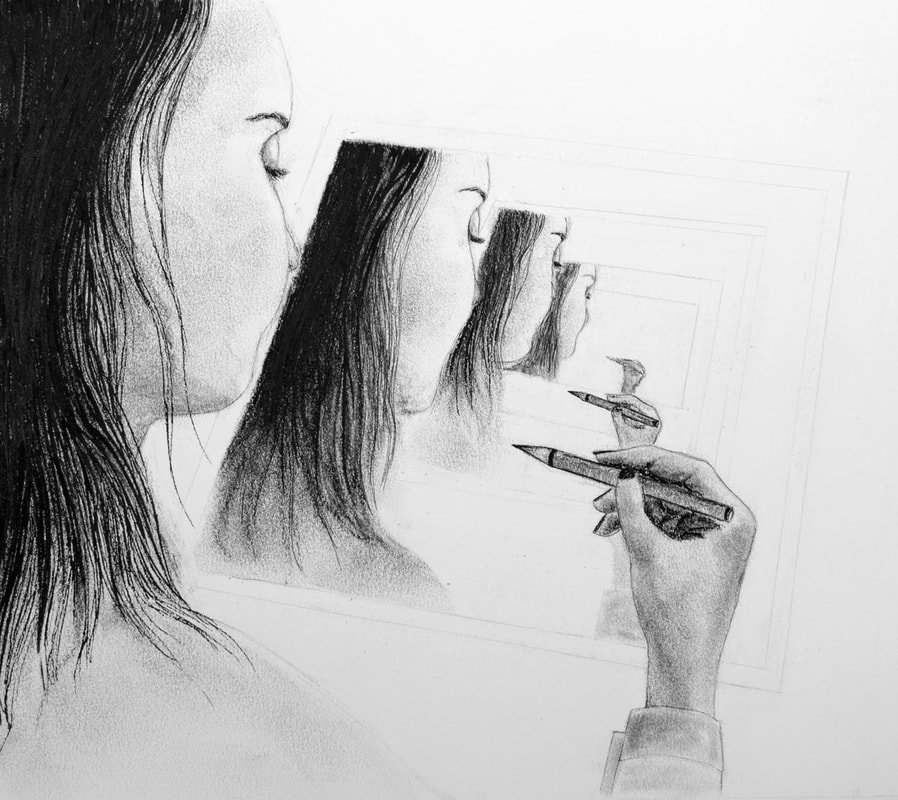

Now picture the illustrator of a comic, charged to render the wonder of physics thought experiments on the page. How might she show that it is remarkable that it works? That it is remarkable that two thinkers can not only share images but compare imaginations? It won’t do to draw exclamations marks outside the shared bubble, because that might only signal that the thinkers are excited about their shared thought, not that it is remarkable that they are having the same thought. In fact, thinkers rarely pause to reflect on how remarkable it is that to do (some) actual physics, they compare imaginations. Our illustrator must appeal to her readers’ sense of incredulity that one thinker can compel another to picture a scenario, set it in motion, and ask questions about what happens. These thinkers launch their imaginations with imperatives like “Suppose” or “Consider” before the picture and the question, such as, “would you agree that a person would not feel her own weight,” etc. Our illustrator marvels at this form of persuasion. How to show that there are rules to the shared imagination? Roads with guard rails to show that we must follow a certain path? But wouldn’t the path, predetermined, beg the question of the thought experiment? The guard rails would have to be nearly transparent, a gentle guide, but not so obvious that the thought experimenter is aware of them. Consider an illustration of the illustrator herself and the panels so far, her pen to mouth in a gesture of puzzlement. Perhaps a series of if-then drawings demonstrating unequivocal causal relationships, showing that the shared imagination has an inevitability to it. She might finally nod in agreement with herself, wouldn’t she?

For the imagery of a thought experiment itself, picture a shared thought bubble between two thinking beings. Now, already this picture is a lie, and I mean this is in a stronger sense than all pictures are mental distortions, simplifications, cartoons. The shared thought bubble is a lie—isn’t it?—because thinking beings, as far as we know, never share the same picture in their minds’ eyes, only approximations based on descriptions.

Suppose I am right so far, and that the shared thought bubble representing a thought experiment is only a sketch of what happens when two thinking beings engage in this kind of physics. We have the cartoon of an idea, its contours only. (And it isn’t as if equations are not involved—this could be shown by drawing equations in thought bubbles—but we must remember that the equations we choose to represent physical phenomena depend on our underlying conceptual scheme, which comes back to pictures. (This, we can suppose, rules out the possibility of someone with aphantasia engaging in the physics of thought experiments, because we are exploring the space where visual—even fantastical—intuitions align.))

Now picture the illustrator of a comic, charged to render the wonder of physics thought experiments on the page. How might she show that it is remarkable that it works? That it is remarkable that two thinkers can not only share images but compare imaginations? It won’t do to draw exclamations marks outside the shared bubble, because that might only signal that the thinkers are excited about their shared thought, not that it is remarkable that they are having the same thought. In fact, thinkers rarely pause to reflect on how remarkable it is that to do (some) actual physics, they compare imaginations. Our illustrator must appeal to her readers’ sense of incredulity that one thinker can compel another to picture a scenario, set it in motion, and ask questions about what happens. These thinkers launch their imaginations with imperatives like “Suppose” or “Consider” before the picture and the question, such as, “would you agree that a person would not feel her own weight,” etc. Our illustrator marvels at this form of persuasion. How to show that there are rules to the shared imagination? Roads with guard rails to show that we must follow a certain path? But wouldn’t the path, predetermined, beg the question of the thought experiment? The guard rails would have to be nearly transparent, a gentle guide, but not so obvious that the thought experimenter is aware of them. Consider an illustration of the illustrator herself and the panels so far, her pen to mouth in a gesture of puzzlement. Perhaps a series of if-then drawings demonstrating unequivocal causal relationships, showing that the shared imagination has an inevitability to it. She might finally nod in agreement with herself, wouldn’t she?

Jessica Reed’s chapbooks include Still Recognizable Forms (Laurel Review Greentower Press) and World, Composed (Finishing Line Press, finalist for the Etchings Press Whirling Prize). Her work has appeared in Conjunctions, Quarterly West, Colorado Review, Chicago Review online, Denver Quarterly, Crazyhorse, Inverted Syntax, Bellingham Review, New American Writing, Exposition Review, The Fourth River, DIAGRAM, [Pank], Scientific American, and elsewhere. https://www.jessicareed.info