Fred Flanders. Flat-Earth Fred. Don't ask me to say Flat-Earth Fred Flanders. It's too hard untie my tongue afterwards.

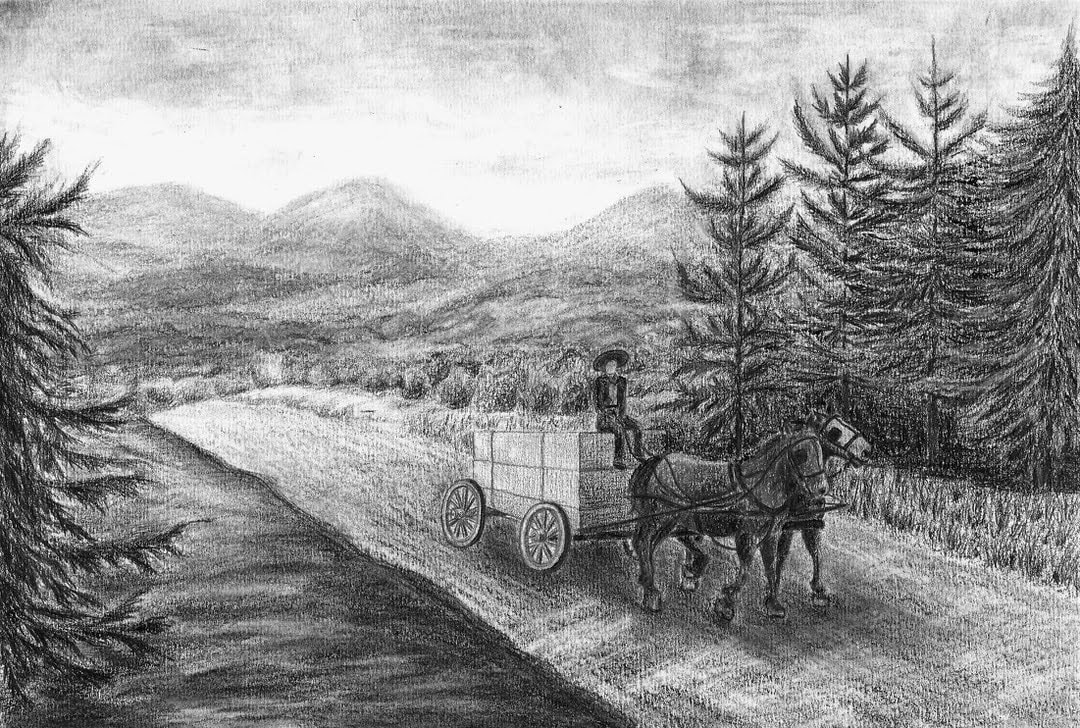

Fred lived far off the grid, a mile and a half from the nearest pavement, hunkering down on an old farmstead at the foot of the Alder Brook Mountains. One could say he was a recluse, making, as he did, an appearance in town four times a year, sitting high on a lumber wagon pulled by a matched pair of black Percherons, a brace of beagles baying from the back. One could also say he was seriously cracked. When he came to Saranac Lake, news of his arrival spread like measles, and the next thing you knew, there'd be a pack of kids dogging him down Main Street, taunting him, chanting, “Flat-Earth Fred; Flat-Earth Fred; how they gonna bury you when you're dead?” He'd cut his eyes at us, wearing a look of withering disdain, not just for his adolescent tormentors but for all of us round-earthers, poor deluded bastards. You could almost hear him thinking it. Well, we round-earthers were thinking the same about him. But the thing about Fred, he didn't merely believe he was right—he knew he was right. His certainty was unshakable; his evidence—to which none of us were privy—incontrovertible.

Another thing about Fred. He hated the State of New York, hated the concept of the Forest Preserve (though he said he loved the forest), hated the Forever Wild Clause of the State Constitution. He swore to anyone who would listen that the State would never get his land, that they already owned too much and didn’t know what to do with it. When he went to the other side, as he put it, he would continue ownership; he would maintain control. “Yeah, yeah. Right, right.” None of us had the faintest inkling that Fred Flanders was loaded, had bags of cash in a half-dozen banks, or that he'd established a trust to pay the taxes on his farm in perpetuity...but he did. And then, one day, he simply vanished.

It's remarkable how people can show concern for someone they have habitually ridiculed. The last time anyone had seen Flat-Earth Fred was in September, on the autumnal equinox. He’d loaded his wagon with supplies as usual and trundled off on his northward journey from Saranac Lake to Alder Brook. When he hadn't returned to town by April, conversation about him acquired an edge of worry. Well, it had been a particularly snowy winter, so it was a very muddy mud season. Maybe Fred was just waiting for things to dry out. His horses weren't getting any younger, and dragging that lumber wagon through a mile and a half of muck holes was maybe a trial he had decided to spare them. But when May passed without Fred coming to town, the ridiculers (now sympathizers) organized a search and rescue party and proceeded to his farm. Everything was as it should have been, with a few notable exceptions. There were no animals—no chickens, no goats, no pigs, no team of Percherons, and no beagles. There was not a speck of food left anywhere, neither for humans nor for critters. And there was no Fred. The search of the surrounding slopes and streams and swamps continued for several more days, turning up nothing of note; after which it was agreed that Fred had up and moved, maybe to someplace where winters didn't last more than five months. There was only one problem with this theory, acknowledged by all but dismissed with a shrug. His wagon was still in the barn and the house was still full of everything one would expect to need to start a new life. The State police and the Conservation Department forest rangers, who had been in on the search, had an alternative view. Fred had either sold or eaten his animals, walked the four miles to the state highway, and stuck his thumb out. Happens all the time.

#

Fifty years after Fred's disappearance, I decided to pay a visit to the place everybody my age new about but few people left living had actually seen. Those of us who were adolescents at the time of Fred's departure had not been invited to the search. For us kids, Fred was just a crazy old coot who lacked the brains to get a driver’s license. We were completely unaware of the majesty of what he was doing. Nor did our parents have much to say about a man who had turned his back on a way of life they had fought a World War to defend—but, though they never noted it, by the time the United States was attacked, Fred was already too old to join the fight. He had come to our attention in the Eisenhower years, after all, when conformity was king. Had it been fifteen years later, he would have been an inspiration to the packs of back-to-the-landers who flocked to the Adirondacks from the late 60s to the late 70s. And no one apparently considered that Fred Flanders may have fought in a prior conflict—or that he had survived gassing in what was then called the Great War—to return home to Utica and, after all the accolades and the triumphant parades and the puffery over how the world had been made safe for democracy, watch helplessly as his wife and his brother were slain by the Spanish flu…a story made known to me by his only Saranac Lake friend, who had sworn not to breathe a word of it to anybody until after Fred was gone; though gone where, the friend did not know.

I followed in reverse the route Flat-Earth Fred followed when he made his quarterly trips to Saranac Lake. As I drove north—out the Bloomingdale Road, then the Fletcher Farm Road, and on to Rock Street which, in Fred's day, was not much of a street (six miles with three houses and no pavement), and as the markers of civilization slipped behind me and the land became emptier and wilder—I could feel the spirit of Fred Flanders drawing near, could see him through the eyes of my memory, could see myself as a ten-year-old standing at the curb on Saranac Lake’s Main Street as Fred made his entry, the two great beasts harnessed to the wagon shafts, the creaking of the straps, clinking of chains, the rumble of the iron-rimmed, oak-spoked wheels as the horses pulled Fred's rig from back roads to state highway to downtown, their massive heads held high, their black coats gleaming, their dark eyes shining like they possessed the key to some secret we humans would never understand. We have all seen the Clydesdales on television hauling the Budweiser beer wagon, prancing, regal. Fred Flanders’ Percherons were something else entirely. They thundered into town like they owned the place. For them, it wasn't about the show. It was about the power, and no one in a car ever made the mistake of getting in their way. Yet, impressed as I was by both him and his horses, I went along with the older boys hounding Flat-Earth Fred, ignoring my instincts, trying to keep my mouth shut but invariably failing, insensitive to the lurking feeling that there was more to this stoop-shouldered, sunbaked, grizzled man than a few peculiar ideas and that perhaps he was deserving of the same respect due anyone who had managed to surpass the age of eighteen.

#

I came into it in a roundabout way, this expedition to Flat-Earth Fred's. His homestead was not, at first, my goal. By the place where the Alder Brook Road bridges the brook itself, there is a view north over marshes that border the stream and northeast to the Alder Brook Mountains. From the highest peak of that range, a spur ridge runs west to a nameless, rock-crowned knob that drops abruptly to the valley floor. For decades, every time I drove that road, I'd stop at the bridge to photograph the scene which always seemed to convey a mood of melancholy enchantment; and I would gaze at the high knob and wonder what it would be like to stand there, on those ledges, and look out over forest and marsh and stream back to where I had been standing by the bridge. One day it dawned on me that from the knob I should be provided a view right down on Fred Flanders’ farm. I could then bushwhack straight south practically to Fred's back door. So, the farm became my goal, then, and the spur and knob the means to get there.

On a brilliant afternoon in the first week of October, I trekked in on an old logging road that skirted the edge of Duncan Mountain over the ends of its western ridges which extend into the valley like toes. The road was straight as a laser for nearly it's entire length through a dark forest of spruce and fir broken occasionally by bands of bright maples, their leaves flashing red and yellow and orange in a light breeze. It came to an end where the land began to rise on the south side of the spur. As I climbed, trailless above the road, the nature of the woods changed from mostly coniferous to mostly deciduous: and, farther up, the maples gave way to birches and aspens, their foliage fluttering butter yellow. At the ridgetop, I turned left, westward, and walked among the pale and slender trunks up an easy incline, crossing two narrow strips of evergreens before scrambling up the knob to the clifftops that were my preliminary destination. From there, I looked almost straight down on my primary destination—the fields of Fred's farm, a tawny swath set in a matrix of the green and gold and crimson of the autumn forest. To the east rose the mass of Duncan Mountain; to the west the floodplain of Alder Brook, the glistening stream embraced by marsh grasses and the water-loving alders from which it derives its name; to the south, the distant, pale blue peaks of the McKenzie Range. And in all that space, with the exception of the patch of pasture and meadow practically at my feet and the little bridge and the snippet of road that crosses it, barely a sign of humankind to be seen. I tried to imagine, but could not, how it must have felt for Fred Flanders to sit upon that rock—as he must have done many times—to look out over this lonesome beauty and call it home.

I retraced my steps from the knob to the spur, then skittered down a steep, dry drainage south until the grade eased and, soon after, I entered Fred’s realm. It was not as cohesive as it had appeared from above. What once had been wide pasture was now fragmented by clusters of hardwoods. South of the farmhouse, though, the land opened up and left me with the sensation, momentarily, of great space, even though I had seen, merely a half hour prior, from the heights to the north, how small and how precious was this breach in the surrounding sea of trees. It left me feeling both comfort and isolation—feelings that would seem to contradict each other but, somehow, in this place, did not.

The fields were mostly tan and brown, the vegetation frost-killed or gone to seed and exhausted. The only intact artifact left on the farm was a masterfully built cobblestone retaining wall in front of the house, supporting it and what had been a lawn on a terrace and separating them from the fields below. The house itself was a ruin. It had been white once but now was more than half grey, the white having flaked off and blown away. The roof was largely caved in. There had been an extensive glass-enclosed veranda. It had collapsed, and the front of the house was guarded by the shards of shattered windows protruding from the grass. The rear of the building was unapproachable, walled off by a tangle of shrubbery gone wild. The barn had completely fallen down. If there was a lumber wagon under the debris, I could not see it. Other smaller auxiliary structures had been reduced to indecipherable heaps of junk.

I tried to visualize all of this whole and undamaged; and, looking at it that way, it became clear to me that the place was too much for one man. This may have been Fred Flanders’ farm, but he hadn't put it here—not a single stick of it. He had bought it complete and “ready for occupancy,” as the realtors say. No, this farm was the legacy of a large and industrious family who had labored here perhaps for generations before the economy became too tough for smalltime agriculture in this remote corner of the Adirondack Highlands, and they sold what they had built with their muscle and their love to the rich man from Utica who wanted only a place to live his life far enough from everything so that people would leave him alone.

Everybody knew about Fred's grievances against the State and how he planned to even the score. Like his flat-earth theories, he made no secret of them. It's just that nobody suspected he had the wherewithal to pull it off. But he had taken ownership, and the trust he'd established owned it still—paying the taxes, keeping it from the grasping hands of the State of New York, (always greedy to take ever more acreage out of private circulation, driven by dreamers of endless wilderness who never would admit to the possibility of enough). But now Fred had been gone fifty years, the enduring irony being that the land he'd succeeded in preventing the State from turning into wilderness before its time (as if a tin sign on a tree can create wilderness by mere declaration) was turning into wilderness anyway...but in its own time; and, perhaps, that would have been acceptable to Fred, wherever he might have gone.

The sun was sinking toward the west, and clouds were approaching from the same direction; yet, despite the threat of darkness and rain, I was reluctant to leave. I wanted to explore the farm more deeply. A sugarbush south of the main fields was particularly enticing. “A half hour,” I told myself. “I'll give it a half hour; then head out.”

A pair or wheel ruts, overgrown by weeds, softened by time, led across the meadow and into the bush, which was parklike in aspect, the sugar maples stately and generously spaced; but there was a haunted feeling to the place, as if those who had created it—long since passed—had not fully departed. Beyond the wreckage of what must have been a sugarhouse, the ruts ended in a small clearing, elliptical and silent—no birds singing, no small rodents scurrying, not even the whisper of a breeze. A few strides into it, I felt the ground sag beneath my weight—not much, but enough to stop me. Then I took another step, hesitant, prepared to leap away should my footing fail. Again, the ground flexing but resilient, my foot sinking but not breaking through. Another step; firm footing. A fourth step; sinking again, but no more than an inch. I removed my daypack, knelt down, pulled a small digging trowel (politically correct personal waste disposal tool) from the pack and proceeded to scrape away several inches of accumulated detritus—last year's leaves at the top; compost at the bottom—until I encountered a surface below the surface. It was verdigris, emitting a metallic sound when tapped. I cleared away more of the organic matter that covered it, then scraped it with the point of my trowel, leaving a shining red-orange scar—copper. I pressed it with my hand. It flexed. I pounded with it with the side of my fist. The timbre of the thumping told me there was a hollow space underneath…and a sizable one, at that. I went to work on it like a hound digging up a bone, and the more I uncovered the faster I dug until the whole thing was revealed.

What I had found was a door made of copper sheathing, with three brass hinges on one side and a pair of stainless steel hasps on the other and stainless steel fasteners all around. It was a big door—big enough to admit a draft horse. The surrounding frame was made of heavily creosoted railroad ties. The hasps were open, and there were no locks. Fred, when he took his leave, must have decided there was no longer any reason to keep this door secured. I grasped the conveniently placed handle with both hands and braced myself for a struggle, but raising the door required almost no effort, assisted as it was by a quartet of pneumatic door openers. The underside of the door revealed that the sheathing had been secured with hundreds of bolts to a frame of aluminum struts. There was also a handle on the inside mirroring the location of the one on the outside.

It was impossible to judge the depth of the opening the door had concealed. Looking down into the hole, it was as black as night. That is to say: not pitch black, not black as coal, but exactly black as night—star-spangled, and with a first-quarter moon hanging in the upper right hand corner. My hands went clammy. I began to tremble. I became disoriented, dizzy, and I felt my legs fold under me. Fortunately, I did not pitch forward. I fell in a sitting position; and sitting I remained on the edge of this doorway to oblivion, awestruck, terrified, and enthralled until I felt the first cold raindrops strike my head. I pushed the door, and the pneumatic openers, now acting as closers, did the rest. The whole contraption, which must have weighed close to hundred pounds, shut without a sound. I covered it with the material I had removed from it as thoroughly as I was able, considering my haste. Then I left the sugarbush and found a wagon road that I guessed must lead to the outside. It soon deteriorated to little more than a path; but I trudged on, the rain pounding, the light failing, having discovered no other paths leading away from the homestead aside from the one ending at the hole in the sugarbush. Barely five minutes after switching on my headlamp, and much to my relief, I emerged onto pavement a half-mile west of where I had left it.

I arrived home in Saranac Lake tired, wet, and hungry. I set the thermostat at 70, shucked my clothes for a pair of flannel lounging pants and a fleece hoodie, pulled a bag of leftover chili from the freezer, microwaved it until it resembled a liquid, and sat down at my kitchen table with this steaming bowl and the day's Adirondack Daily Enterprise in front of me. I read one sentence but could not read more. I did little better with the chili—two spoons full before I gave it up. I couldn't eat. And I could not think about anything but the vision that had confronted me from the depths of that hole beneath the green copper door.

What had I seen? That was not the question. The question was: was it real? And, if it was real, what did it mean? I would have to go back—at night—to either prove or dispel what I feared was true and earnestly wished was a lie. So I resolved to do it—not immediately but when I had regained my composure…and my courage.

#

Three nights later I parked my truck off the shoulder of the county road at Saint Rose of Lima Cemetery, Alder Brook. I strapped on my pack and my headlamp, walked to the spot where I had exited the woods some 72 hours earlier, and dove into the enveloping darkness. When I arrived at the farm, I stopped and looked up at the infinite sky, seemingly alive with its countless stars, its unblinking planets, and its slice of moon. Was this firmament a reflection of what I had seen through a hole in the earth ringed by watchful maples, guardians at the threshold? And would I see it again when I opened the green door? Or would I see something else? I had no idea. But I was sure of one thing. I was afraid.

I asked the sky and the earth, the forest and the fields, and whatever creatures might be willing to listen to the likes of me—a human where humans no longer belonged—for protection, for a clear mind, for a calm heart; and I followed the beam of my headlamp into the sugarbush. I cleared away the leaves and sticks and humus I had spread on the door at my prior departure, grasped the handle, and pulled. It was immediately obvious that what lay beneath was not the same as what I had seen before. As soon as the edge of the door cleared the surface, a warm light escaped to illuminate the ground, the toes of my boots, the feet of the trees behind me. I hesitated for a moment and almost let go of the handle to allow the opening to reseal itself. Then I thought of Fred Flanders. What would have been his assessment of a grown man who, when this close to revealing his secret, had backed away like a shy ten-year-old? Why would Fred leave this door unlocked if he didn't want it to be opened? But what if it was a trap? It was a thought that skipped through my mind, then sank out of sight. The Fred I knew when I was a boy was eccentric—many said crazy—and he was gruff and sometimes haughty. He could be mean when mercilessly antagonized, but he was never malevolent. Not even close.

“No,” I thought. “There's nothing here to fear.” And I flung the door wide open.

The light blared out like a fanfare of trumpets. It blew me off my feet; knocked the breath out of me. I lay on my back for several minutes, propped myself on my elbows, and then took a sitting position several yards from the rim while my eyes adjusted to the beam of light shooting upwards seemingly to the stars. Eventually, I was able to skooch my way to the edge, only to be more astounded than I had been on my first encounter. Looking into the hole was like looking up at a sunny summer day—fluffy white clouds drifting across a robin's-egg sky. I must have sat there, motionless, for fully an hour, bathed in that mid-afternoon glow in the middle of the night, watching that endless cloud parade. Disorienting as the night view had been in daylight, this was even more confounding because I could see the other end of the hole, which seemed ridiculously close—not much more than six feet, judging by the number of railroad ties that lined it in its entirety and by the number of rungs on the ladder that descended into it. I picked up a small pebble and dropped it in out of random curiosity. It fell a little beyond halfway, then slowed and stopped before rising back up, stopping again and remaining suspended as if trapped between opposing gravitational fields. I stared at this chip of defiant matter until my eyes watered. Or was I crying, overwhelmed by the shattering of my complacent arrogance and the upending of the limits of what I had thought possible?

I had a notion, fleeting but compelling, that the ladder was for me, that I should descend it and push through the barrier that had arrested the pebble's fall. Fortunately, fleeting outweighed compelling. I walked around to the hinged side of the door and gave it a sharp shove. As they had three and a half days earlier, the pneumatics took it from there. Just before the final sliver of daylight was extinguished by the closing door, I heard a muffled snort and what sounded like the stamp of a big hoof upon packed soil…accompanied by the faint smell of equine sweat on hot leather. I made a move toward the handle to pull back on it; but I was too late. The door fell fully shut, and the sound and the smell were gone. I replaced the forest litter more carefully this time, trying to match the original layering, with the oldest material at the bottom and the newest at the top.

It was incredibly dark without the big hole blasting daylight into the night. As I prepared to leave the sugarbush and head across the meadow, the beam of my lamp seemed pitifully meek, but I got used to it; and, by the time I finished my work and shouldered my pack, it struck me as almost normal, while the reburied glory would forever be an aberration. But what kind of aberration? Sitting upon the cobblestone wall, waiting for dawn, I was left to grapple with the question: just what was it that I had found? Was it the entry to another world? Or was it a portal to the other side of this one? Or was it a hallucination…or a dream? That would mean the aberration was simply an aberration of the mind. I didn't want to believe I had been hallucinating. That would make me as crazy as Flat-Earth Fred. As for dreams, there was always the light switch test.

A narcoleptic friend of mine often experiences dreams within dreams, sometimes in multiple layers. She'll awaken from a dream only to find she's, in fact, awakened into another dream. This can leave her wondering, no matter how many times she wakes up, if she is truly awake. That's where light switches come into play. In her dreams, and in mine as well, artificial illumination is frightfully unreliable. Flip a switch, and nothing happens…or the light that results is so feeble as to barely extend beyond a lampshade, leaving the darkness all around, pressing implacably inward, threatening to snuff out the light and the dreamer along with it. So, to prove she is really awake, she finds a light switch and, if it works, she knows she's no longer asleep. But there were no light switches at hand on that wall at Fred Flanders' farm. Still, I did have my headlamp. I switched it off and then switched it back on. It wasn't much, but it was something; and that would have to be enough.

So, what lay beneath the copper door was still an aberration, but at least it was a real one, a passageway, perhaps, to a parallel reality. Would I ever muster the courage to come back and climb down that ladder? I doubted it at the time, but that was a dozen years ago, and I find myself thinking that I am twelve years less doubtful. As we draw nearer to the end of our term on this particular plane of existence, maybe we become more willing to explore alternatives.

#

Now, there is only one last nagging question. If the farm had been combed by dozens of searchers on that long-ago spring when Fred Flanders' absence was finally noticed, why hadn't the copper door been found then? Could these trained men—many of them forest rangers and State troopers—actually have missed an opening that Fred could have coaxed his Percherons through? It lay practically in the middle of what, in those days, would have been a road. I found it when it was covered with half a century's worth of rotting leaves, and I was just wandering around, not really looking for anything.

Over time, I have accumulated a number of possible answers ranging from the reasonable to those that defy reason. If it is true that the simplest explanation is most likely correct, then here's what happened. Though the odds were against it, the searchers missed the door. They were near it—maybe only inches away—but they never saw it and never stepped on it. Granted, it was under at least one year's leaf fall. Nevertheless, I find the idea pretty hard to swallow.

The explanation I prefer is that the searchers discovered the door, opened it, and saw nothing but an empty pit. Why Fred Flanders should put such an elaborate door over a hole in the ground was anybody's guess; but, hey, they were talking about Flat-Earth Fred, and that was all the explanation they needed. They closed the door on the stars and the moon and the midnight sky and walked away, asking no further questions. They had not perceived what was actually there because what was there broke all the rules. They had not been ready for the impossible.

#

Time slips from under me like bald tires on black ice. The years have numbers, now, and they are not in my favor. Maybe when my turn comes to pass to the other side—whether it's the other side of this life or the other side of this world—I'll be able to declare, “I know where there's a shortcut.” And perhaps when I get there, wherever there may be, the first person I'll see will be Flat-Earth Fred; and the first thing he'll say to me will be, “I told you so.”

Fred lived far off the grid, a mile and a half from the nearest pavement, hunkering down on an old farmstead at the foot of the Alder Brook Mountains. One could say he was a recluse, making, as he did, an appearance in town four times a year, sitting high on a lumber wagon pulled by a matched pair of black Percherons, a brace of beagles baying from the back. One could also say he was seriously cracked. When he came to Saranac Lake, news of his arrival spread like measles, and the next thing you knew, there'd be a pack of kids dogging him down Main Street, taunting him, chanting, “Flat-Earth Fred; Flat-Earth Fred; how they gonna bury you when you're dead?” He'd cut his eyes at us, wearing a look of withering disdain, not just for his adolescent tormentors but for all of us round-earthers, poor deluded bastards. You could almost hear him thinking it. Well, we round-earthers were thinking the same about him. But the thing about Fred, he didn't merely believe he was right—he knew he was right. His certainty was unshakable; his evidence—to which none of us were privy—incontrovertible.

Another thing about Fred. He hated the State of New York, hated the concept of the Forest Preserve (though he said he loved the forest), hated the Forever Wild Clause of the State Constitution. He swore to anyone who would listen that the State would never get his land, that they already owned too much and didn’t know what to do with it. When he went to the other side, as he put it, he would continue ownership; he would maintain control. “Yeah, yeah. Right, right.” None of us had the faintest inkling that Fred Flanders was loaded, had bags of cash in a half-dozen banks, or that he'd established a trust to pay the taxes on his farm in perpetuity...but he did. And then, one day, he simply vanished.

It's remarkable how people can show concern for someone they have habitually ridiculed. The last time anyone had seen Flat-Earth Fred was in September, on the autumnal equinox. He’d loaded his wagon with supplies as usual and trundled off on his northward journey from Saranac Lake to Alder Brook. When he hadn't returned to town by April, conversation about him acquired an edge of worry. Well, it had been a particularly snowy winter, so it was a very muddy mud season. Maybe Fred was just waiting for things to dry out. His horses weren't getting any younger, and dragging that lumber wagon through a mile and a half of muck holes was maybe a trial he had decided to spare them. But when May passed without Fred coming to town, the ridiculers (now sympathizers) organized a search and rescue party and proceeded to his farm. Everything was as it should have been, with a few notable exceptions. There were no animals—no chickens, no goats, no pigs, no team of Percherons, and no beagles. There was not a speck of food left anywhere, neither for humans nor for critters. And there was no Fred. The search of the surrounding slopes and streams and swamps continued for several more days, turning up nothing of note; after which it was agreed that Fred had up and moved, maybe to someplace where winters didn't last more than five months. There was only one problem with this theory, acknowledged by all but dismissed with a shrug. His wagon was still in the barn and the house was still full of everything one would expect to need to start a new life. The State police and the Conservation Department forest rangers, who had been in on the search, had an alternative view. Fred had either sold or eaten his animals, walked the four miles to the state highway, and stuck his thumb out. Happens all the time.

#

Fifty years after Fred's disappearance, I decided to pay a visit to the place everybody my age new about but few people left living had actually seen. Those of us who were adolescents at the time of Fred's departure had not been invited to the search. For us kids, Fred was just a crazy old coot who lacked the brains to get a driver’s license. We were completely unaware of the majesty of what he was doing. Nor did our parents have much to say about a man who had turned his back on a way of life they had fought a World War to defend—but, though they never noted it, by the time the United States was attacked, Fred was already too old to join the fight. He had come to our attention in the Eisenhower years, after all, when conformity was king. Had it been fifteen years later, he would have been an inspiration to the packs of back-to-the-landers who flocked to the Adirondacks from the late 60s to the late 70s. And no one apparently considered that Fred Flanders may have fought in a prior conflict—or that he had survived gassing in what was then called the Great War—to return home to Utica and, after all the accolades and the triumphant parades and the puffery over how the world had been made safe for democracy, watch helplessly as his wife and his brother were slain by the Spanish flu…a story made known to me by his only Saranac Lake friend, who had sworn not to breathe a word of it to anybody until after Fred was gone; though gone where, the friend did not know.

I followed in reverse the route Flat-Earth Fred followed when he made his quarterly trips to Saranac Lake. As I drove north—out the Bloomingdale Road, then the Fletcher Farm Road, and on to Rock Street which, in Fred's day, was not much of a street (six miles with three houses and no pavement), and as the markers of civilization slipped behind me and the land became emptier and wilder—I could feel the spirit of Fred Flanders drawing near, could see him through the eyes of my memory, could see myself as a ten-year-old standing at the curb on Saranac Lake’s Main Street as Fred made his entry, the two great beasts harnessed to the wagon shafts, the creaking of the straps, clinking of chains, the rumble of the iron-rimmed, oak-spoked wheels as the horses pulled Fred's rig from back roads to state highway to downtown, their massive heads held high, their black coats gleaming, their dark eyes shining like they possessed the key to some secret we humans would never understand. We have all seen the Clydesdales on television hauling the Budweiser beer wagon, prancing, regal. Fred Flanders’ Percherons were something else entirely. They thundered into town like they owned the place. For them, it wasn't about the show. It was about the power, and no one in a car ever made the mistake of getting in their way. Yet, impressed as I was by both him and his horses, I went along with the older boys hounding Flat-Earth Fred, ignoring my instincts, trying to keep my mouth shut but invariably failing, insensitive to the lurking feeling that there was more to this stoop-shouldered, sunbaked, grizzled man than a few peculiar ideas and that perhaps he was deserving of the same respect due anyone who had managed to surpass the age of eighteen.

#

I came into it in a roundabout way, this expedition to Flat-Earth Fred's. His homestead was not, at first, my goal. By the place where the Alder Brook Road bridges the brook itself, there is a view north over marshes that border the stream and northeast to the Alder Brook Mountains. From the highest peak of that range, a spur ridge runs west to a nameless, rock-crowned knob that drops abruptly to the valley floor. For decades, every time I drove that road, I'd stop at the bridge to photograph the scene which always seemed to convey a mood of melancholy enchantment; and I would gaze at the high knob and wonder what it would be like to stand there, on those ledges, and look out over forest and marsh and stream back to where I had been standing by the bridge. One day it dawned on me that from the knob I should be provided a view right down on Fred Flanders’ farm. I could then bushwhack straight south practically to Fred's back door. So, the farm became my goal, then, and the spur and knob the means to get there.

On a brilliant afternoon in the first week of October, I trekked in on an old logging road that skirted the edge of Duncan Mountain over the ends of its western ridges which extend into the valley like toes. The road was straight as a laser for nearly it's entire length through a dark forest of spruce and fir broken occasionally by bands of bright maples, their leaves flashing red and yellow and orange in a light breeze. It came to an end where the land began to rise on the south side of the spur. As I climbed, trailless above the road, the nature of the woods changed from mostly coniferous to mostly deciduous: and, farther up, the maples gave way to birches and aspens, their foliage fluttering butter yellow. At the ridgetop, I turned left, westward, and walked among the pale and slender trunks up an easy incline, crossing two narrow strips of evergreens before scrambling up the knob to the clifftops that were my preliminary destination. From there, I looked almost straight down on my primary destination—the fields of Fred's farm, a tawny swath set in a matrix of the green and gold and crimson of the autumn forest. To the east rose the mass of Duncan Mountain; to the west the floodplain of Alder Brook, the glistening stream embraced by marsh grasses and the water-loving alders from which it derives its name; to the south, the distant, pale blue peaks of the McKenzie Range. And in all that space, with the exception of the patch of pasture and meadow practically at my feet and the little bridge and the snippet of road that crosses it, barely a sign of humankind to be seen. I tried to imagine, but could not, how it must have felt for Fred Flanders to sit upon that rock—as he must have done many times—to look out over this lonesome beauty and call it home.

I retraced my steps from the knob to the spur, then skittered down a steep, dry drainage south until the grade eased and, soon after, I entered Fred’s realm. It was not as cohesive as it had appeared from above. What once had been wide pasture was now fragmented by clusters of hardwoods. South of the farmhouse, though, the land opened up and left me with the sensation, momentarily, of great space, even though I had seen, merely a half hour prior, from the heights to the north, how small and how precious was this breach in the surrounding sea of trees. It left me feeling both comfort and isolation—feelings that would seem to contradict each other but, somehow, in this place, did not.

The fields were mostly tan and brown, the vegetation frost-killed or gone to seed and exhausted. The only intact artifact left on the farm was a masterfully built cobblestone retaining wall in front of the house, supporting it and what had been a lawn on a terrace and separating them from the fields below. The house itself was a ruin. It had been white once but now was more than half grey, the white having flaked off and blown away. The roof was largely caved in. There had been an extensive glass-enclosed veranda. It had collapsed, and the front of the house was guarded by the shards of shattered windows protruding from the grass. The rear of the building was unapproachable, walled off by a tangle of shrubbery gone wild. The barn had completely fallen down. If there was a lumber wagon under the debris, I could not see it. Other smaller auxiliary structures had been reduced to indecipherable heaps of junk.

I tried to visualize all of this whole and undamaged; and, looking at it that way, it became clear to me that the place was too much for one man. This may have been Fred Flanders’ farm, but he hadn't put it here—not a single stick of it. He had bought it complete and “ready for occupancy,” as the realtors say. No, this farm was the legacy of a large and industrious family who had labored here perhaps for generations before the economy became too tough for smalltime agriculture in this remote corner of the Adirondack Highlands, and they sold what they had built with their muscle and their love to the rich man from Utica who wanted only a place to live his life far enough from everything so that people would leave him alone.

Everybody knew about Fred's grievances against the State and how he planned to even the score. Like his flat-earth theories, he made no secret of them. It's just that nobody suspected he had the wherewithal to pull it off. But he had taken ownership, and the trust he'd established owned it still—paying the taxes, keeping it from the grasping hands of the State of New York, (always greedy to take ever more acreage out of private circulation, driven by dreamers of endless wilderness who never would admit to the possibility of enough). But now Fred had been gone fifty years, the enduring irony being that the land he'd succeeded in preventing the State from turning into wilderness before its time (as if a tin sign on a tree can create wilderness by mere declaration) was turning into wilderness anyway...but in its own time; and, perhaps, that would have been acceptable to Fred, wherever he might have gone.

The sun was sinking toward the west, and clouds were approaching from the same direction; yet, despite the threat of darkness and rain, I was reluctant to leave. I wanted to explore the farm more deeply. A sugarbush south of the main fields was particularly enticing. “A half hour,” I told myself. “I'll give it a half hour; then head out.”

A pair or wheel ruts, overgrown by weeds, softened by time, led across the meadow and into the bush, which was parklike in aspect, the sugar maples stately and generously spaced; but there was a haunted feeling to the place, as if those who had created it—long since passed—had not fully departed. Beyond the wreckage of what must have been a sugarhouse, the ruts ended in a small clearing, elliptical and silent—no birds singing, no small rodents scurrying, not even the whisper of a breeze. A few strides into it, I felt the ground sag beneath my weight—not much, but enough to stop me. Then I took another step, hesitant, prepared to leap away should my footing fail. Again, the ground flexing but resilient, my foot sinking but not breaking through. Another step; firm footing. A fourth step; sinking again, but no more than an inch. I removed my daypack, knelt down, pulled a small digging trowel (politically correct personal waste disposal tool) from the pack and proceeded to scrape away several inches of accumulated detritus—last year's leaves at the top; compost at the bottom—until I encountered a surface below the surface. It was verdigris, emitting a metallic sound when tapped. I cleared away more of the organic matter that covered it, then scraped it with the point of my trowel, leaving a shining red-orange scar—copper. I pressed it with my hand. It flexed. I pounded with it with the side of my fist. The timbre of the thumping told me there was a hollow space underneath…and a sizable one, at that. I went to work on it like a hound digging up a bone, and the more I uncovered the faster I dug until the whole thing was revealed.

What I had found was a door made of copper sheathing, with three brass hinges on one side and a pair of stainless steel hasps on the other and stainless steel fasteners all around. It was a big door—big enough to admit a draft horse. The surrounding frame was made of heavily creosoted railroad ties. The hasps were open, and there were no locks. Fred, when he took his leave, must have decided there was no longer any reason to keep this door secured. I grasped the conveniently placed handle with both hands and braced myself for a struggle, but raising the door required almost no effort, assisted as it was by a quartet of pneumatic door openers. The underside of the door revealed that the sheathing had been secured with hundreds of bolts to a frame of aluminum struts. There was also a handle on the inside mirroring the location of the one on the outside.

It was impossible to judge the depth of the opening the door had concealed. Looking down into the hole, it was as black as night. That is to say: not pitch black, not black as coal, but exactly black as night—star-spangled, and with a first-quarter moon hanging in the upper right hand corner. My hands went clammy. I began to tremble. I became disoriented, dizzy, and I felt my legs fold under me. Fortunately, I did not pitch forward. I fell in a sitting position; and sitting I remained on the edge of this doorway to oblivion, awestruck, terrified, and enthralled until I felt the first cold raindrops strike my head. I pushed the door, and the pneumatic openers, now acting as closers, did the rest. The whole contraption, which must have weighed close to hundred pounds, shut without a sound. I covered it with the material I had removed from it as thoroughly as I was able, considering my haste. Then I left the sugarbush and found a wagon road that I guessed must lead to the outside. It soon deteriorated to little more than a path; but I trudged on, the rain pounding, the light failing, having discovered no other paths leading away from the homestead aside from the one ending at the hole in the sugarbush. Barely five minutes after switching on my headlamp, and much to my relief, I emerged onto pavement a half-mile west of where I had left it.

I arrived home in Saranac Lake tired, wet, and hungry. I set the thermostat at 70, shucked my clothes for a pair of flannel lounging pants and a fleece hoodie, pulled a bag of leftover chili from the freezer, microwaved it until it resembled a liquid, and sat down at my kitchen table with this steaming bowl and the day's Adirondack Daily Enterprise in front of me. I read one sentence but could not read more. I did little better with the chili—two spoons full before I gave it up. I couldn't eat. And I could not think about anything but the vision that had confronted me from the depths of that hole beneath the green copper door.

What had I seen? That was not the question. The question was: was it real? And, if it was real, what did it mean? I would have to go back—at night—to either prove or dispel what I feared was true and earnestly wished was a lie. So I resolved to do it—not immediately but when I had regained my composure…and my courage.

#

Three nights later I parked my truck off the shoulder of the county road at Saint Rose of Lima Cemetery, Alder Brook. I strapped on my pack and my headlamp, walked to the spot where I had exited the woods some 72 hours earlier, and dove into the enveloping darkness. When I arrived at the farm, I stopped and looked up at the infinite sky, seemingly alive with its countless stars, its unblinking planets, and its slice of moon. Was this firmament a reflection of what I had seen through a hole in the earth ringed by watchful maples, guardians at the threshold? And would I see it again when I opened the green door? Or would I see something else? I had no idea. But I was sure of one thing. I was afraid.

I asked the sky and the earth, the forest and the fields, and whatever creatures might be willing to listen to the likes of me—a human where humans no longer belonged—for protection, for a clear mind, for a calm heart; and I followed the beam of my headlamp into the sugarbush. I cleared away the leaves and sticks and humus I had spread on the door at my prior departure, grasped the handle, and pulled. It was immediately obvious that what lay beneath was not the same as what I had seen before. As soon as the edge of the door cleared the surface, a warm light escaped to illuminate the ground, the toes of my boots, the feet of the trees behind me. I hesitated for a moment and almost let go of the handle to allow the opening to reseal itself. Then I thought of Fred Flanders. What would have been his assessment of a grown man who, when this close to revealing his secret, had backed away like a shy ten-year-old? Why would Fred leave this door unlocked if he didn't want it to be opened? But what if it was a trap? It was a thought that skipped through my mind, then sank out of sight. The Fred I knew when I was a boy was eccentric—many said crazy—and he was gruff and sometimes haughty. He could be mean when mercilessly antagonized, but he was never malevolent. Not even close.

“No,” I thought. “There's nothing here to fear.” And I flung the door wide open.

The light blared out like a fanfare of trumpets. It blew me off my feet; knocked the breath out of me. I lay on my back for several minutes, propped myself on my elbows, and then took a sitting position several yards from the rim while my eyes adjusted to the beam of light shooting upwards seemingly to the stars. Eventually, I was able to skooch my way to the edge, only to be more astounded than I had been on my first encounter. Looking into the hole was like looking up at a sunny summer day—fluffy white clouds drifting across a robin's-egg sky. I must have sat there, motionless, for fully an hour, bathed in that mid-afternoon glow in the middle of the night, watching that endless cloud parade. Disorienting as the night view had been in daylight, this was even more confounding because I could see the other end of the hole, which seemed ridiculously close—not much more than six feet, judging by the number of railroad ties that lined it in its entirety and by the number of rungs on the ladder that descended into it. I picked up a small pebble and dropped it in out of random curiosity. It fell a little beyond halfway, then slowed and stopped before rising back up, stopping again and remaining suspended as if trapped between opposing gravitational fields. I stared at this chip of defiant matter until my eyes watered. Or was I crying, overwhelmed by the shattering of my complacent arrogance and the upending of the limits of what I had thought possible?

I had a notion, fleeting but compelling, that the ladder was for me, that I should descend it and push through the barrier that had arrested the pebble's fall. Fortunately, fleeting outweighed compelling. I walked around to the hinged side of the door and gave it a sharp shove. As they had three and a half days earlier, the pneumatics took it from there. Just before the final sliver of daylight was extinguished by the closing door, I heard a muffled snort and what sounded like the stamp of a big hoof upon packed soil…accompanied by the faint smell of equine sweat on hot leather. I made a move toward the handle to pull back on it; but I was too late. The door fell fully shut, and the sound and the smell were gone. I replaced the forest litter more carefully this time, trying to match the original layering, with the oldest material at the bottom and the newest at the top.

It was incredibly dark without the big hole blasting daylight into the night. As I prepared to leave the sugarbush and head across the meadow, the beam of my lamp seemed pitifully meek, but I got used to it; and, by the time I finished my work and shouldered my pack, it struck me as almost normal, while the reburied glory would forever be an aberration. But what kind of aberration? Sitting upon the cobblestone wall, waiting for dawn, I was left to grapple with the question: just what was it that I had found? Was it the entry to another world? Or was it a portal to the other side of this one? Or was it a hallucination…or a dream? That would mean the aberration was simply an aberration of the mind. I didn't want to believe I had been hallucinating. That would make me as crazy as Flat-Earth Fred. As for dreams, there was always the light switch test.

A narcoleptic friend of mine often experiences dreams within dreams, sometimes in multiple layers. She'll awaken from a dream only to find she's, in fact, awakened into another dream. This can leave her wondering, no matter how many times she wakes up, if she is truly awake. That's where light switches come into play. In her dreams, and in mine as well, artificial illumination is frightfully unreliable. Flip a switch, and nothing happens…or the light that results is so feeble as to barely extend beyond a lampshade, leaving the darkness all around, pressing implacably inward, threatening to snuff out the light and the dreamer along with it. So, to prove she is really awake, she finds a light switch and, if it works, she knows she's no longer asleep. But there were no light switches at hand on that wall at Fred Flanders' farm. Still, I did have my headlamp. I switched it off and then switched it back on. It wasn't much, but it was something; and that would have to be enough.

So, what lay beneath the copper door was still an aberration, but at least it was a real one, a passageway, perhaps, to a parallel reality. Would I ever muster the courage to come back and climb down that ladder? I doubted it at the time, but that was a dozen years ago, and I find myself thinking that I am twelve years less doubtful. As we draw nearer to the end of our term on this particular plane of existence, maybe we become more willing to explore alternatives.

#

Now, there is only one last nagging question. If the farm had been combed by dozens of searchers on that long-ago spring when Fred Flanders' absence was finally noticed, why hadn't the copper door been found then? Could these trained men—many of them forest rangers and State troopers—actually have missed an opening that Fred could have coaxed his Percherons through? It lay practically in the middle of what, in those days, would have been a road. I found it when it was covered with half a century's worth of rotting leaves, and I was just wandering around, not really looking for anything.

Over time, I have accumulated a number of possible answers ranging from the reasonable to those that defy reason. If it is true that the simplest explanation is most likely correct, then here's what happened. Though the odds were against it, the searchers missed the door. They were near it—maybe only inches away—but they never saw it and never stepped on it. Granted, it was under at least one year's leaf fall. Nevertheless, I find the idea pretty hard to swallow.

The explanation I prefer is that the searchers discovered the door, opened it, and saw nothing but an empty pit. Why Fred Flanders should put such an elaborate door over a hole in the ground was anybody's guess; but, hey, they were talking about Flat-Earth Fred, and that was all the explanation they needed. They closed the door on the stars and the moon and the midnight sky and walked away, asking no further questions. They had not perceived what was actually there because what was there broke all the rules. They had not been ready for the impossible.

#

Time slips from under me like bald tires on black ice. The years have numbers, now, and they are not in my favor. Maybe when my turn comes to pass to the other side—whether it's the other side of this life or the other side of this world—I'll be able to declare, “I know where there's a shortcut.” And perhaps when I get there, wherever there may be, the first person I'll see will be Flat-Earth Fred; and the first thing he'll say to me will be, “I told you so.”

Phil Gallos has been a newspaper reporter and columnist, a researcher/writer in the historic preservation field, and has spent 33 years working in academic libraries (which is more interesting than it sounds). His stories have been published in The Writing Disorder, STORGY Magazine, Dark Moon Lilith, Wisconsin Review, Defunkt Magazine, and Blueline among others. He lives and writes in Saranac Lake, NY.