SANJA

[January, Solni trg]

[January, Solni trg]

The snow outside and the snow-white cloth inside, in front of me, with nothing but an empty red plate to cancel this utter, blinding whiteness. In a moment mother shall call and I shall pretend that my phone is too deep inside my handbag for me to hear it. Did you not promise to change, I whisper to myself, as I lit yet another cigarette – this is not a proper way to start one’s days. But I do not answer; I only ask questions and carry on all the same. My peripheral sight catches a glimpse of a person moving on the right – a beautiful contrast of a shadow against the snow, but no one comes. The table is still empty, as is the plate and the ashtray too full, as is my mind. How do I stop?

Mother said she does not understand: her life was a different life; Perhaps it is enough to acknowledge that different generations have it differently, she said, And be done with it. So she says, but she calls and asks the same questions and makes the same demands wrapped into neat little sentences of passive-aggressive advice. I listen to them, then burn them like cigarettes. There are no simple lives; only simple questions.

Something swoops down towards me from the milky sky, snatching me back from the aimless mental eddying: a pigeon bangs its body and flaps its wings against the window pane of the winter garden. Is that us, banging our bodies against the actuality of life? I ask. Another shadow rushes past on the left, then turns with a spin like a gyrating dervish: ‘What would You like?’

Mother said she does not understand: her life was a different life; Perhaps it is enough to acknowledge that different generations have it differently, she said, And be done with it. So she says, but she calls and asks the same questions and makes the same demands wrapped into neat little sentences of passive-aggressive advice. I listen to them, then burn them like cigarettes. There are no simple lives; only simple questions.

Something swoops down towards me from the milky sky, snatching me back from the aimless mental eddying: a pigeon bangs its body and flaps its wings against the window pane of the winter garden. Is that us, banging our bodies against the actuality of life? I ask. Another shadow rushes past on the left, then turns with a spin like a gyrating dervish: ‘What would You like?’

SAU

[October, Gorkého 2/12]

[October, Gorkého 2/12]

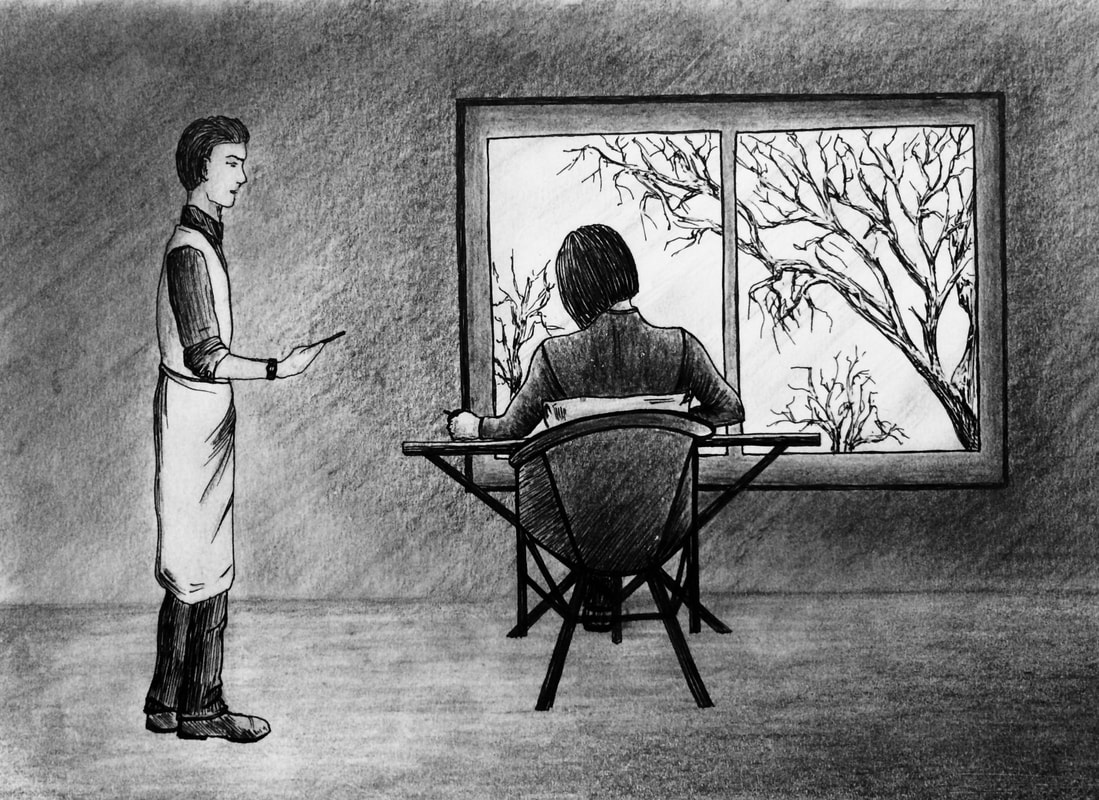

―It seems like a sequence of pointless attempts at the same thing. The branches can grow all they like, they still remain part of the tree. – says Evá, her hands and arms forming a semi-circle on the table, wrapping around a green cup of English Breakfast with milk.

All this fuss about relationships? I ask.

―Well, relationships too, but life in general is what I meant. It is a sequence of pointless attempts to make the fragments come together and remain that way. A rather silly idea, when you think about it, this that anything can ever be yoked together despite its parts clearly pulling it asunder.

But, branches can grow all they like, they still remain part of the tree – you said that, I contradict.

―I did, didn’t I? But I did not mean it like that. The two were not . . . the same thing . . .

Here a chatter from the other end of the room swallows her words and nothing reaches me but snippets. I divert my eyes towards the window in the fashion of a somebody who is trying to discern what the other person has just said. Not me, I think. I fill myself like a cup and empty myself but remain who I am. What attempts is she talking about?

― . . . but then he wanted to be present in everything, and that is simply not a sane demand on anyone; I thought we were attempting something fundamentally different. Aren’t people tired of the same old thing by now? – she comes back into the focus.

No, not really; creatures of habits, I say.

―Well, let them evolve already. Or at least stop hindering the evolution of others.

That would require for the change itself to become a habit, I retort. A server emerges from behind the numerous tables, collecting the cups and the glasses: ‘Anything else for You?’

The same, we both return.

All this fuss about relationships? I ask.

―Well, relationships too, but life in general is what I meant. It is a sequence of pointless attempts to make the fragments come together and remain that way. A rather silly idea, when you think about it, this that anything can ever be yoked together despite its parts clearly pulling it asunder.

But, branches can grow all they like, they still remain part of the tree – you said that, I contradict.

―I did, didn’t I? But I did not mean it like that. The two were not . . . the same thing . . .

Here a chatter from the other end of the room swallows her words and nothing reaches me but snippets. I divert my eyes towards the window in the fashion of a somebody who is trying to discern what the other person has just said. Not me, I think. I fill myself like a cup and empty myself but remain who I am. What attempts is she talking about?

― . . . but then he wanted to be present in everything, and that is simply not a sane demand on anyone; I thought we were attempting something fundamentally different. Aren’t people tired of the same old thing by now? – she comes back into the focus.

No, not really; creatures of habits, I say.

―Well, let them evolve already. Or at least stop hindering the evolution of others.

That would require for the change itself to become a habit, I retort. A server emerges from behind the numerous tables, collecting the cups and the glasses: ‘Anything else for You?’

The same, we both return.

MÁRIÁN

[July, Ferenczy István u. 5]

[July, Ferenczy István u. 5]

I sit down first; then Ilona comes in and Tibor follows; her cheeks flushed with the heat, his pale and dry like paper. We have been meandering in the summer heaviness.

―So, next summer we definitely have to go for a trip around Europe together; you will come back and Ilona will be finished here, Canada will still be a few months away – we’ll make it the most memorable summer of our lives, Tibor says.

We all exchange assuring looks, smiles and nods. Perhaps we even believe our own words; certainly, earlier we have all seen people keeping their word or not dying before the set date. Tibor’s fingers coil in the most magnificent ways as he handles his teacup for the new ‘Egészségedre’.

It often seems to me we do not really live much beyond the musings of will or shall. But I give my best to absorb this moment and its tiny details orbiting around it like planets around suns: if I am to remember, let me remember his coiling fingers and her tulip cheekbones; perhaps a desired kiss upon my sunburnt lips (it will never occur; how marvellous!) and certainly the muted chink of our ceramic teacups in the summer parchedness. This memorable July.

It feels good, being finished with it all – the studies over, the thesis defended and another paper for the world that runs on degrees and honours – in stock. How happy does it really make one on the scale from well done to what's next? We seem to long for others and true epiphanies and adventures but always end up adding yet another written proof to the tower of Babylon of our experience that yields nothing but melancholy, like hot wind sweeping over a sun-dried savannah.

You, then, Ilona and Tibor are what I desire – your company, your body movements, your silly wandering eyes, the way you hold your teacups – to be exposed to these daily. Still, more than anything I seem to lead a life of parting; always coming and always going and so am never able to continuously witness these tiny miracles, momentary flashings, fleeting scents . . . Is it this that can explain it, the particular flood of pleasure that I get out of goodbyes? Perhaps I’ve only learnt to cope with the choice of lifestyle I’ve made? Is the pleasure of goodbyes nothing but a thing I persuaded myself to feel in order to get past the empty structures and the mental quicksand?

―So, what does it feel like to be done with it? – says Ilona.

―It feels . . . finished. – says Tibor.

Nothing special, I add. We can rush off to new things; sharks must always continue swimming.

―And I’ve got another year to fight out with this monster; you two are so lucky.

Depends. You see, I say, you’ve got it all sorted. One more year here, than Canada, Tibor, a whole life together. I am still on point zero; I must wriggle on but naturally I can’t just go about aimlessly – what lies ahead is equally nerve-wracking as what lies behind.

―Oh, but you are a genius, Máriánuš! You will rise above all of this. And my God you are so cute! – Ilona says.

―Yes, we were saying the other night how cute you are! – Tibor adds.

To many of these encounters! I say, raising my cup.

― Egészségedre! – Ilona returns, to which we finish our teas.

―But, before we go, do we want anything else? – Tibor says.

―So, next summer we definitely have to go for a trip around Europe together; you will come back and Ilona will be finished here, Canada will still be a few months away – we’ll make it the most memorable summer of our lives, Tibor says.

We all exchange assuring looks, smiles and nods. Perhaps we even believe our own words; certainly, earlier we have all seen people keeping their word or not dying before the set date. Tibor’s fingers coil in the most magnificent ways as he handles his teacup for the new ‘Egészségedre’.

It often seems to me we do not really live much beyond the musings of will or shall. But I give my best to absorb this moment and its tiny details orbiting around it like planets around suns: if I am to remember, let me remember his coiling fingers and her tulip cheekbones; perhaps a desired kiss upon my sunburnt lips (it will never occur; how marvellous!) and certainly the muted chink of our ceramic teacups in the summer parchedness. This memorable July.

It feels good, being finished with it all – the studies over, the thesis defended and another paper for the world that runs on degrees and honours – in stock. How happy does it really make one on the scale from well done to what's next? We seem to long for others and true epiphanies and adventures but always end up adding yet another written proof to the tower of Babylon of our experience that yields nothing but melancholy, like hot wind sweeping over a sun-dried savannah.

You, then, Ilona and Tibor are what I desire – your company, your body movements, your silly wandering eyes, the way you hold your teacups – to be exposed to these daily. Still, more than anything I seem to lead a life of parting; always coming and always going and so am never able to continuously witness these tiny miracles, momentary flashings, fleeting scents . . . Is it this that can explain it, the particular flood of pleasure that I get out of goodbyes? Perhaps I’ve only learnt to cope with the choice of lifestyle I’ve made? Is the pleasure of goodbyes nothing but a thing I persuaded myself to feel in order to get past the empty structures and the mental quicksand?

―So, what does it feel like to be done with it? – says Ilona.

―It feels . . . finished. – says Tibor.

Nothing special, I add. We can rush off to new things; sharks must always continue swimming.

―And I’ve got another year to fight out with this monster; you two are so lucky.

Depends. You see, I say, you’ve got it all sorted. One more year here, than Canada, Tibor, a whole life together. I am still on point zero; I must wriggle on but naturally I can’t just go about aimlessly – what lies ahead is equally nerve-wracking as what lies behind.

―Oh, but you are a genius, Máriánuš! You will rise above all of this. And my God you are so cute! – Ilona says.

―Yes, we were saying the other night how cute you are! – Tibor adds.

To many of these encounters! I say, raising my cup.

― Egészségedre! – Ilona returns, to which we finish our teas.

―But, before we go, do we want anything else? – Tibor says.

V. B. Borjen (b.1987) writes in two languages and reads in four. His short stories, essays, articles and literary translations have appeared in various Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, Hungarian, and Montenegrin magazines and dailies. The manuscript of his first poetry collection Priručnik za levitiranje (Levitation Manual) won the prestigious Mak Dizdar Award in 2012 and was published the following year to significant acclaim. In the same year his poem "Momento mori" was published in Hypothetical: A Review of Everything Imaginable, followed by a (still informative) interview. He is a doctoral candidate and lives in the Czech Republic, where he reads (on the trams, the trains, the street corners, in the cafes, on the toilet, between the lessons, while queuing or doing the washing up) and writes, Tumblrs his favourite literature and art and Instagrams his own ink drawings and silliness. Tweets as well, but too sporadically.