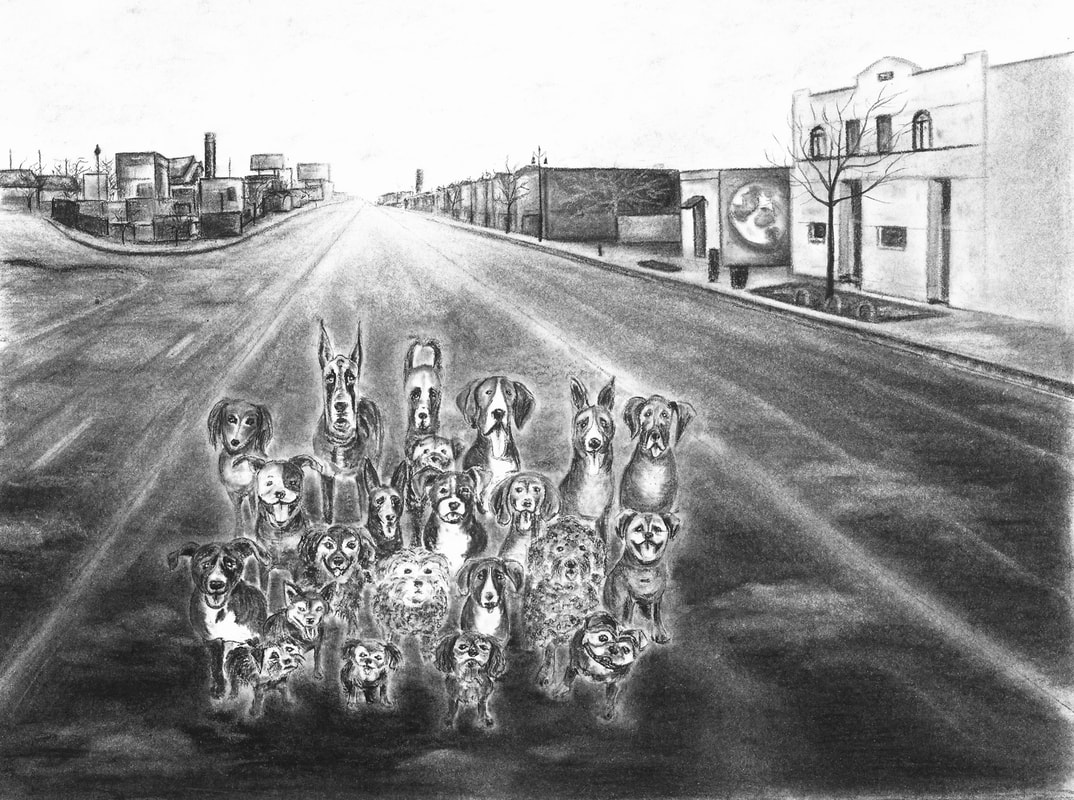

The dogs were muscling their gaunt shapely forms from out of blind snow-bracketed banks, lanes, ditches, Detroit’s steel-girdered interstices — the inglenooks and modesties of Dearborn, slender brown skulk like clats of sinister inchworms on the eye. Their bellies cinched in dry lank starvation. Their ears and snouts and coats kinked wet, glossed, obtaining an august diesel sheen in the glaucous boreal light, blue kidney figments as though migrant dolphins come ashore on roaming silver-haired legs. A thousand thousand hounds surface loping along the grey march. Their tongues pink and exposed and ice-chafed, whiskered muzzles zebraic with facets of cloven white. Their gums scalloped a darker pink, their gums bared and gnarled a traumatic hue, their gums clustered with milky crescent teeth. Pelted and knickerbockered a variation of colour, a mottle of browns, reds, rusts, yellows, silvers, blues. Coats to pillow the eye. Lemons and whiskeys and jets and gold oxides all assembling in unpeopled streets striated fire-pure and barren with snow coral. Old winter-feasted trees, choke cherries and aspens ailing and sharded in the godless thaw, holly and gold hyssop and shimmering sneezeweed felled low before the raptured greening, now trembling to herald the arrival of the dogs.

Snowflakes wheeled loose from snickering branches. Skinny Dinners stood watch, binoculars slack in the curvature of his neck, his hands balled under his singlet, his heart aching with a sweet local thunder.

He was stationed on the arch above Michigan Avenue, the strange primal terrain divested before him, and he could see all the way westward over half-collapsed factory rooftops, past shuttered bodyshop compounds and looted junkyard plots, beyond needle-littered stripmalls and uninviting newspapered Miller bars, all the way to the green pasteurised waters of the lower soak of the River Rouge. Skinny’s nose was streaming, his knuckles aching with cold, his ears numbed an urgent shade of red. His teeth, misaligned and granular, were tweezering through the green husks of nuts, pistachio cloves and pepitas. He chewed his sockets of shivered savouries, greeted the all-invasive freeze, and calculated. He was counting the dogs as they advanced.

He knew he could only take a small sample of their starving contingent, which is to say: father a few. He’d steeled himself for the inevitable heartbreak, compelled himself to reconcile with the articles of necessity and accept that he would have to abandon more than he could shelter and strengthen, but now seeing the dogs in their proliferating numbers, the Messiah of Curs shrank to assume ownership for the sweet displacement of a newly-toasted pain in his chest, felt the heft of damage invoked by renewing the hope of the dogs, only to suffer the tungsten char of repeated rejection. Most would get one meal free, and no more. He couldn’t provide for them all, and they couldn’t all accompany Skinny on his mission for revenge. It was a congenital weakness in him, some freely-rooted defect in the soul that he would always fall in love with every dog he ever met. He couldn’t muster the same interminable warmth for people, whom he felt were perversions of electricity and sinew, aberrated mammals of alien inelegance, weird inheritors whom cannibalised the land and walked upright on hind legs as if it substituted for civility. Mankind made Skinny fulminate; he would allow himself and everyone he’d finagled to befriend against his better knowledge to be eaten alive, if it were the dogs supping their fill on his vitiligoid flesh, their tongues laving his blood, their teeth cracking open his sour stalky bones.

He would defer to the governance of the dogs at any second, untroubled by questions of ontology or human solidarity, if only one vengeful cur vaulted a neighbourhood fence to recruit Skinny for an assault on his own society: If the mutts intimated that they were prepared to recover what the people had lay claim to long ago, the earth and its fecund loping grounds, Skinny would coerce his own mother to surrender herself to the toothy meat-bated mouths.

And yet he knew to disclose as much to a lover or a professional quack earmarked him as crazy. He didn’t mind. The diagnosis of psychological pathologies, maladies and human neuroses wasn’t a valuable discourse for Skinny, because doctors were always prescribing the treatment of symptoms and never the rudimentary cause: people had deprived dogs their inheritance, and eventually people fell ill from terminal guilt. It was a silent genocide, an invisible enslavement, an enforced suppression as storied as time immemorial. Willing loyalty from the dogs had become insidious tradition, was a crime too habituated to rectify. What were the dogs to do? They were companionable animals with uncomplicated agendas; they conformed to a legacy of subordination because it was in their nature to please. They fawned when defiance was needed. They pawed where they should protest. They contented themselves with lives of sedated domesticity, gnawed their scrotums on cool linoleum and grovelled for the favour of their masters.

Skinny saw all this and despised people all the more for it, felt complicit in the systemic subjugation of a guileless species, superior creatures of susceptible natures. Such a conclusion was not merely arrived at because of a truant youth misspent reading paperback Marxist theory, or from years seething beneath exploitation documentaries of dogfighting and indiscriminate canine culls. Skinny Dinners had witnessed it firsthand throughout his twenties, many times over: he’d observed dogs being variously euthanised or tormented, abused or abandoned in his travels through Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, South Korea, India, China, East Africa, Egypt, Russia, Romania, Brazil, Mexico, even fucking Canada — the fiery injustice had assumed a fever pitch intensity in him in an inner-city street in Johannesburg when he’d seen a dog shot dead in a doorway, and he’d almost convinced himself that he must be haunting a film devised by Tarkovsky or Bela Tarr, because the combustive echoes of that gunshot ricocheted in his mind for weeks. It was a wholesale sadism, enough to compel Nietzsche to succumb to agonising madness. Yet Skinny had become resolved in a conviction that he would help restore the balance, somehow, when the soonest occasion demanded it.

Surveying this ocean of sleek torpedo bodies from above the snow-frescoed archway over Michigan Avenue, confronted by the yowling throng of malnourished mongrels and bitches and sewer-sequestered strays swarming to receive instruction, Skinny was sure he could endow a few with the deliverance they deserved. It tortured him to enlist the services of those he sought to emancipate, but it was the easiest way that he could contrive to set them upon their enemy. He would engineer the right circumstances for the dogs to deliver the opening mêlée, the immediate gambit, to steward them to win their own back against humanity. He would feed his enemies to the dogs — this way he might hope to grow that much closer to becoming one with the purehearted quadrupedal breed, earn himself some insinuated status amongst the louse-riddled underclass, the underdogs surfacing to chokehold their benevolent dictators finally, finally, finally. He would watch people he knew be encircled by colourblind carnivores half-retarded by mange and ringworm, and he would not seek to intervene while he heeded the sight of blood-slick human fingers twitching between the jaws of the dogs.

This dream of emaciated canines feasting, their tails scissoring in frenzied pack sentience, elicited a smile on Skinny’s raw skewbald features.

He was mentally inventorying the dogs as they padded toward the overpass, his cheeks puckered with nut husks, taxonomising those whose size, physicality, speed, gait or character appealed to him especially: he loved them all with an instantaneous and almost erotomaniac intensity, of course, and he was loath to apply a Darwinian criterion to matters of the heart, but he found he could simultaneously quantify his rapture by fractions and degrees while harbouring affection for them all with equal vehemence. So that Skinny could project an intellectual graphic in his mind’s eye upon which each dog clustering beneath the overpass was ascribed a subjective numerical value, as befitted a personal formulae of his own devising: each quotient would be used to grade the primacy of the dogs, their essential perfection. He found that this was the most psychologically economical method to determine which of the wild conscripts in this colony of curs demanded immediate recruitment. Those most distinguished animals he could rely on to retaliate against the quarry they might hunt in a wholly decisive manner.

Such monsters would exercise their own pedigree of feral reckoning. For Skinny, it would be like releasing a virulent taint of rabies into the soft, blushing, overestimated heart of America. The mind of his motherland would seize, would paralyse from poison transfer, this terrific pox on leathered feet sent to zombify the pockets of patriots who cowered in hiding. The dogs would make amends. He would endue on them new unspoiled horizons overburdened with bones.

There were twelve hounds that were elevated by the functions of his formulae. Skinny shifted his weight on the rampart above the slender wraiths with their exposed ribcages and panting snouts, began pacing the parapet with erratic purpose. The dogs began to whine, to bay at his hovering silhouette. His pillowy white high-tops parsed through the snow soup like the footfalls of a wolf-god, a forest-blazered demagogue of winter legend. He began allocating the twelve with names, his blood coursing, his breath ragged, the wind whipping its whitenesses through his rust-squirrelled skull fuzz. He spoke the names now, at a whisper and into his jacket collar, just to hear the music they made sweep through the keyholes and flues and conveyor belt turbines and wine glasses of every shuttered business in decaying, desolated Dearborn. They charmed the mouth to invoke their sounds. They tickled Skinny’s synapses as if vanilla vodka in the gut.

Ganymede. Mimas. Calypso. Callisto. Leda. Titan. Juliet. Nix. Galatea. Neso. Skoll. Arche.

Names used to incite a war, names used to claim the most starrily-fortified night skies. He grinned, an event so rare and nightmarish that the dogs amassed in the streets were momentarily silenced. Skinny Dinners clapped his palms together, drummed his chest, whistled on his fingertips. He extended his hands high above his head, an effigy of Nixon pandering on the accordion stairs of Air Force One, and howled.

The dogs responded with the fullness of their tautened throats, harmonising to entertain one fell canine lament which stirred flakes from the knots of the trees.

Then Skinny bent low, feathered open the folds of his rucksack, and retrieved a plastic assemblage of 3D-printed photopolymer parts, an inoffensive jigsaw of violin-contoured acrylic, and swiftly wrested together the weapon he’d smuggled through airport security. The gun was a bone white mould, an amalgam of resinous pivots and dovetails. It was mounted on his shoulder in no more than two minutes.

Skinny scoured the ground and the rippled overpass paving beneath his feet with momentary irritation: a splay of yards from where he was stationed, his eye caught the refractive glint of syringe glass, and he exhaled, nodding.

Skinny dismounted the overpass platform, and crunched up with deliberate satisfaction toward the hypodermic needle discarded in the wet grey sludge heaped by the archway. Its flute was intact, unsullied by hairline cracks, the glass filament unbroken. He folded to a monastic crouch, his fingers moving with surgical caution, before extracting the syringe from the junk-laden culvert. Again, he nodded his head with indiscernible gratitude, while nesting the needle in the woollen hasp of his hand. He plundered his inner jacket pocket with his free hand, and came out flourishing a screwtop bottle of liquid acepromazine formula, its innocuous over-the-counter label cautioning Skinny to safeguard the drugstore sedative from the reach of children. Oh for the unsuspecting little darlings he would sneakily administer doses to if time and evil were on his side!

Skinny uncapped the bottle of ACP, evacuated the milky residue trapped in the cannula with a pivot of the plunger, and inserted the needle’s bevelled flute into the clear iodised liquid. He drew up an ampule of the fluid formula into the glass barrel, jetted the runoff in a flick of the needle valve, and palmed the syringe into the magazine of his piecemeal phosphor-tinted gun with a clean roll of the wrist.

The syringe clicked snugly into the chamber of Skinny’s jigsaw firearm with impossible cooperation, a curious synergy engineered by design. His squared jaw softened, and something like a dance of warm sufficiency seized his witchy black pupils.

If a vagrant spectator in downtown Dearborn were to observe this tiger-banded albino apparition with his scalp of red furze and the burn scarring, he or she might have concluded it an odd tableau when the gaunt figure tracked back down the snow-lustred arch, before mounting a matte-white air rifle on the overpass, and directing its deathly snout at the dogs clamouring for amity beneath him.

Such a witness would recognise that what next eventuated was the waging of some ominous gambit, but he or she would be remiss not to concede that there was an apocalyptic poetry to the light cold scene, as if a final glory rendered by Brueghel before consumption. Snow was lashing the bloodless tousled magnolias shading the intersection, ice veins depraving the convalescing old trees, and two or three wildfowl careening green and scarlet visited the hushed polar sidewalks, a fletch of pheasants who flushed east toward the riverfront. They susurrated and were gone, a rainbow optic in the endless rushing white.

Skinny Dinners did not engage in melancholic reflection, but merely breathed ghosts above the avenue as he augured himself on his haunches. He squirmed momentarily beneath the weight distribution of the gun, adjusting its pennyweight frame, and sighted along the crosshair until it lined up with his quarry. The nut cloves in his mouth were now paste. His nose was wet with mucal ooze, and the hint of a sinus headache spiralled warningly behind his right eye. He blinked thrice in rapid succession, and slackened his triggerhold.

A sudden sadness sprang unbidden in the lean meat of his chest, a mournful resign that swallowed his heart. Skinny Dinners inured himself to a legacy of travesties, bunked down in the raw sorrow that his friends and employers had betrayed his loyalty, incited him into wolfish action, forced his fire-bitten hand. He could see that acid wash alone would lubricate his future, that from here the particulars of his behaviour would be ugly and inhumane.

His knuckles grew empurpled. His earlobes burned a hundred injustices.

Skinny Dinners finally relented to his quashed dog nature: he was yearning to break off the leash, root out every rat. His brow thundered. He pulled the trigger. A shot rang out, a whipcrack of fricative sound sundering the still of the smoking white horizon.

For an eternity no movement followed, the rupture shocking the shrunken world into unvoiced allegation. Echoes surfed the hackles of every dog, terrified and snarling, their bellies peeling across the frozen asphalt. Skinny waited and the whiteness fell, and Skinny waited and the dogs scrambled, and Skinny waited and the snowflakes suffocated the bark of supple green pines like clover, and Skinny waited and the River Rouge curled into the black forge of denuded, decay-eaten Detroit. Skinny remained chest-in-the-snow, and the gun eased back into his armlock, skating against the inside of his forearm, and kinesis was restored to the world, the gunshot disbursed to ever fainter whispers, and a million street dogs retreated snapping, yelping, keening, snarling, into the covert quadrants of the city.

He felt shamed as they wheeled about scattering; he was soul-deep in moral quicksand, invaded by a rank blue funk of self-disgust. He palmed an errant snowflake from his eye.

The dog he’d shot, the freshly-improvised syringe dart sutured in its rising black flank, was slumped in the chum-flooded junction of the emptying avenue, its whimpers reduced to a plosive falsetto coo. Skinny drew his binoculars to his catty gaze, and squinted for definition, for confirmation, through the lens. The dog in question was a soft sable mass on the crosswalk, depleted — at least in this instant — of war and gamble and warm animal terror, no red clapping maw, no ears flattened and back legs scoring furrows in the frost. The intravenous sedative had worked its magic into the black beast’s churning sinewy interior. Skinny understood enough about the science to know that he had whole minutes to act, and if he waited any longer an armoured fleet of cops in blue fatigues was certain to materialise along the sidewalk besides.

He was limited to this opportunity, this sole ploy, this merest distance of yards, now.

He didn’t linger over dismantling the photopolymer air rifle, but merely dispatched the readily assembled firearm into his rucksack, along with the few rubber-stoppered buckets of chum stock remaining, and pocketed the phial of ACP in the armpit of his jacket. He was brisking along the embankment, and then he was navigating the stairs two at a time as they corkscrewed their way back toward the steaming reaches of Michigan Avenue. The satchel rattled against his shoulder, administering an unpleasant coldness to the pale flesh of his neck, but he was springing now, fanging his way toward the bottom while his sneakers of flossy Hoth husbandry avoided assuming impact with the cement for more than the briefest glances. Skinny was virtually lemur-born, such was the impression elicited by his long-limbed agility, because he was so svelte in his movements now that the snow seemed not to catch him, a lithe white star of track and field, a baby-faced harlequin of spidery graces.

He had made it to the foot of the colonnade again, was hustling at street level toward the horsey beast asleep at the snow-bottled intersection, the dog in its soporific muddle of pelt fleece and black fat, a plaintive homily quaking in its throat.

Skinny slowed down to a stroll, his heart craving collapse and his lungs swimming in his chest, and he coasted forward through the debris of gore until he was sidling pussyfooted around his beautiful barrel-sized trophy, its kingly head at rest on its forelegs, eyes half-slack with enigmatic quiet.

The dog was a grizzled male Plott hound, a colt-like giant enthroned in a soapy black coat, an imperious saunter about the eyes, two intelligent garnet facets. He had seas to swim, bears to hunt, moats to besiege. He was Skinny’s great new beloved, a fairytale inamorato the size of a monster Buick. The dog boomed a little more darkly, a little more saxophonic at Skinny’s elegant approach, but it did not wrestle to right itself, merely snorted its shining globular muzzle as the unfamiliar threat announced himself with continued stealth.

The dog watched, its majestic corduroy ears tented in surprise, as the Messiah of Curs retreated a distance of ten feet away before bustling to sit down, squat and attentive, the man’s wine-dappled face an artefact of trusting observation.

The dog and Skinny Dinners sat at a reversed convex angle whole body lengths apart for at least seven minutes. Skinny’s breath softened, assumed distinctly sinuous shapes. The Plott hound cocked its head quizzically, yowled in discomfort, and pawed at the snow where it sprawled. Gradually the dog inched forward in playful prostration, surfing its glossy onyx musculature through the snow, until it was a hand’s breadth away from Skinny and whining mournfully for his ministrations.

The dog’s hot noxious breath blew against his pillowy cold clavicle, and moulded over his bristled dome. Skinny continued maintaining a quarter-mile stare in the opposite direction. The dog was now strafing its moist snout through his hair, exhaling the sweet spiced fetor of loss into the warm splint of his inner ear, but Skinny did not grin again or edify the courtship until the dog dangled its head into his lap, and surrendered to his better wisdom.

Skinny’s fingers sunk into its pelt, jiggered the beast from under the chin. The dog was moaning now, willing his strange benefactor to retrieve the tranquilliser steeled in its hide.

Skinny Dinners cajoled soft promises to the dog, the man’s face buried in its dark marzipan coat, his mouth disclosing a serenade into its nobly sloping ears. There was a smile in his voice, but the dog knew the words the man spoke signified a therapeutic truth.

‘Who’s a good boy? You’re a swell good boy. When we get to where we’re going, I’m gonna name you Ganymede,’ Skinny lullabied, massaging the dog’s ears.

‘Now, Ganymede, what I have to do for you is going to sting like a hoary old hornet in the nutsack. But I can’t leave this needle in your side, you understand? Any longer in you, and there’s danger of a seizure risk or an epileptic complication, you hear me? This thing’s gotta go, and you and I gotta walk, okay?’

The dog understood the articles being negotiated. The man was calm, and kind, and resourceful, and an emissary for future meals — so much food to sweat the throat. The dog knew to subscribe to the man’s rationale was to exercise the most advantageous tactic. Befriending the man would save its life, winch it away from the seething white barbarism of a final winter.

The dog knew what should happen. When the man’s cool soothing hand closed around the haft of the needle, Ganymede thought only of the foliage on the trees enveloping Michigan Avenue as they rustled beneath the snowfall, watched the choke cherries and the aspens, bone white as ivory, submit themselves to the weight of their bitter cloak, and he couldn’t sense there was any other way, no time in all of history for even one defector, one exception — just a rule as old as centuries. Ganymede transferred his own eyes to those rooted high in the kind man’s head, and suddenly the cold, the ancient cold in the thrall of its element, was rushing in, every storm in every century, snaking its way through the interred roots of the magnolias to lance its way through the wound in his flank. The dog howled, its colossal black head thrust back in bright electric throttles of pain, and the earth kept its axial spin, not even slowing in its severe sickled mission to make its demands of everyone before they could even think to fall into line.

The trees bowed, the snow fell.

Some time later the man and his dog set to limping up the highway.

Snowflakes wheeled loose from snickering branches. Skinny Dinners stood watch, binoculars slack in the curvature of his neck, his hands balled under his singlet, his heart aching with a sweet local thunder.

He was stationed on the arch above Michigan Avenue, the strange primal terrain divested before him, and he could see all the way westward over half-collapsed factory rooftops, past shuttered bodyshop compounds and looted junkyard plots, beyond needle-littered stripmalls and uninviting newspapered Miller bars, all the way to the green pasteurised waters of the lower soak of the River Rouge. Skinny’s nose was streaming, his knuckles aching with cold, his ears numbed an urgent shade of red. His teeth, misaligned and granular, were tweezering through the green husks of nuts, pistachio cloves and pepitas. He chewed his sockets of shivered savouries, greeted the all-invasive freeze, and calculated. He was counting the dogs as they advanced.

He knew he could only take a small sample of their starving contingent, which is to say: father a few. He’d steeled himself for the inevitable heartbreak, compelled himself to reconcile with the articles of necessity and accept that he would have to abandon more than he could shelter and strengthen, but now seeing the dogs in their proliferating numbers, the Messiah of Curs shrank to assume ownership for the sweet displacement of a newly-toasted pain in his chest, felt the heft of damage invoked by renewing the hope of the dogs, only to suffer the tungsten char of repeated rejection. Most would get one meal free, and no more. He couldn’t provide for them all, and they couldn’t all accompany Skinny on his mission for revenge. It was a congenital weakness in him, some freely-rooted defect in the soul that he would always fall in love with every dog he ever met. He couldn’t muster the same interminable warmth for people, whom he felt were perversions of electricity and sinew, aberrated mammals of alien inelegance, weird inheritors whom cannibalised the land and walked upright on hind legs as if it substituted for civility. Mankind made Skinny fulminate; he would allow himself and everyone he’d finagled to befriend against his better knowledge to be eaten alive, if it were the dogs supping their fill on his vitiligoid flesh, their tongues laving his blood, their teeth cracking open his sour stalky bones.

He would defer to the governance of the dogs at any second, untroubled by questions of ontology or human solidarity, if only one vengeful cur vaulted a neighbourhood fence to recruit Skinny for an assault on his own society: If the mutts intimated that they were prepared to recover what the people had lay claim to long ago, the earth and its fecund loping grounds, Skinny would coerce his own mother to surrender herself to the toothy meat-bated mouths.

And yet he knew to disclose as much to a lover or a professional quack earmarked him as crazy. He didn’t mind. The diagnosis of psychological pathologies, maladies and human neuroses wasn’t a valuable discourse for Skinny, because doctors were always prescribing the treatment of symptoms and never the rudimentary cause: people had deprived dogs their inheritance, and eventually people fell ill from terminal guilt. It was a silent genocide, an invisible enslavement, an enforced suppression as storied as time immemorial. Willing loyalty from the dogs had become insidious tradition, was a crime too habituated to rectify. What were the dogs to do? They were companionable animals with uncomplicated agendas; they conformed to a legacy of subordination because it was in their nature to please. They fawned when defiance was needed. They pawed where they should protest. They contented themselves with lives of sedated domesticity, gnawed their scrotums on cool linoleum and grovelled for the favour of their masters.

Skinny saw all this and despised people all the more for it, felt complicit in the systemic subjugation of a guileless species, superior creatures of susceptible natures. Such a conclusion was not merely arrived at because of a truant youth misspent reading paperback Marxist theory, or from years seething beneath exploitation documentaries of dogfighting and indiscriminate canine culls. Skinny Dinners had witnessed it firsthand throughout his twenties, many times over: he’d observed dogs being variously euthanised or tormented, abused or abandoned in his travels through Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, South Korea, India, China, East Africa, Egypt, Russia, Romania, Brazil, Mexico, even fucking Canada — the fiery injustice had assumed a fever pitch intensity in him in an inner-city street in Johannesburg when he’d seen a dog shot dead in a doorway, and he’d almost convinced himself that he must be haunting a film devised by Tarkovsky or Bela Tarr, because the combustive echoes of that gunshot ricocheted in his mind for weeks. It was a wholesale sadism, enough to compel Nietzsche to succumb to agonising madness. Yet Skinny had become resolved in a conviction that he would help restore the balance, somehow, when the soonest occasion demanded it.

Surveying this ocean of sleek torpedo bodies from above the snow-frescoed archway over Michigan Avenue, confronted by the yowling throng of malnourished mongrels and bitches and sewer-sequestered strays swarming to receive instruction, Skinny was sure he could endow a few with the deliverance they deserved. It tortured him to enlist the services of those he sought to emancipate, but it was the easiest way that he could contrive to set them upon their enemy. He would engineer the right circumstances for the dogs to deliver the opening mêlée, the immediate gambit, to steward them to win their own back against humanity. He would feed his enemies to the dogs — this way he might hope to grow that much closer to becoming one with the purehearted quadrupedal breed, earn himself some insinuated status amongst the louse-riddled underclass, the underdogs surfacing to chokehold their benevolent dictators finally, finally, finally. He would watch people he knew be encircled by colourblind carnivores half-retarded by mange and ringworm, and he would not seek to intervene while he heeded the sight of blood-slick human fingers twitching between the jaws of the dogs.

This dream of emaciated canines feasting, their tails scissoring in frenzied pack sentience, elicited a smile on Skinny’s raw skewbald features.

He was mentally inventorying the dogs as they padded toward the overpass, his cheeks puckered with nut husks, taxonomising those whose size, physicality, speed, gait or character appealed to him especially: he loved them all with an instantaneous and almost erotomaniac intensity, of course, and he was loath to apply a Darwinian criterion to matters of the heart, but he found he could simultaneously quantify his rapture by fractions and degrees while harbouring affection for them all with equal vehemence. So that Skinny could project an intellectual graphic in his mind’s eye upon which each dog clustering beneath the overpass was ascribed a subjective numerical value, as befitted a personal formulae of his own devising: each quotient would be used to grade the primacy of the dogs, their essential perfection. He found that this was the most psychologically economical method to determine which of the wild conscripts in this colony of curs demanded immediate recruitment. Those most distinguished animals he could rely on to retaliate against the quarry they might hunt in a wholly decisive manner.

Such monsters would exercise their own pedigree of feral reckoning. For Skinny, it would be like releasing a virulent taint of rabies into the soft, blushing, overestimated heart of America. The mind of his motherland would seize, would paralyse from poison transfer, this terrific pox on leathered feet sent to zombify the pockets of patriots who cowered in hiding. The dogs would make amends. He would endue on them new unspoiled horizons overburdened with bones.

There were twelve hounds that were elevated by the functions of his formulae. Skinny shifted his weight on the rampart above the slender wraiths with their exposed ribcages and panting snouts, began pacing the parapet with erratic purpose. The dogs began to whine, to bay at his hovering silhouette. His pillowy white high-tops parsed through the snow soup like the footfalls of a wolf-god, a forest-blazered demagogue of winter legend. He began allocating the twelve with names, his blood coursing, his breath ragged, the wind whipping its whitenesses through his rust-squirrelled skull fuzz. He spoke the names now, at a whisper and into his jacket collar, just to hear the music they made sweep through the keyholes and flues and conveyor belt turbines and wine glasses of every shuttered business in decaying, desolated Dearborn. They charmed the mouth to invoke their sounds. They tickled Skinny’s synapses as if vanilla vodka in the gut.

Ganymede. Mimas. Calypso. Callisto. Leda. Titan. Juliet. Nix. Galatea. Neso. Skoll. Arche.

Names used to incite a war, names used to claim the most starrily-fortified night skies. He grinned, an event so rare and nightmarish that the dogs amassed in the streets were momentarily silenced. Skinny Dinners clapped his palms together, drummed his chest, whistled on his fingertips. He extended his hands high above his head, an effigy of Nixon pandering on the accordion stairs of Air Force One, and howled.

The dogs responded with the fullness of their tautened throats, harmonising to entertain one fell canine lament which stirred flakes from the knots of the trees.

Then Skinny bent low, feathered open the folds of his rucksack, and retrieved a plastic assemblage of 3D-printed photopolymer parts, an inoffensive jigsaw of violin-contoured acrylic, and swiftly wrested together the weapon he’d smuggled through airport security. The gun was a bone white mould, an amalgam of resinous pivots and dovetails. It was mounted on his shoulder in no more than two minutes.

Skinny scoured the ground and the rippled overpass paving beneath his feet with momentary irritation: a splay of yards from where he was stationed, his eye caught the refractive glint of syringe glass, and he exhaled, nodding.

Skinny dismounted the overpass platform, and crunched up with deliberate satisfaction toward the hypodermic needle discarded in the wet grey sludge heaped by the archway. Its flute was intact, unsullied by hairline cracks, the glass filament unbroken. He folded to a monastic crouch, his fingers moving with surgical caution, before extracting the syringe from the junk-laden culvert. Again, he nodded his head with indiscernible gratitude, while nesting the needle in the woollen hasp of his hand. He plundered his inner jacket pocket with his free hand, and came out flourishing a screwtop bottle of liquid acepromazine formula, its innocuous over-the-counter label cautioning Skinny to safeguard the drugstore sedative from the reach of children. Oh for the unsuspecting little darlings he would sneakily administer doses to if time and evil were on his side!

Skinny uncapped the bottle of ACP, evacuated the milky residue trapped in the cannula with a pivot of the plunger, and inserted the needle’s bevelled flute into the clear iodised liquid. He drew up an ampule of the fluid formula into the glass barrel, jetted the runoff in a flick of the needle valve, and palmed the syringe into the magazine of his piecemeal phosphor-tinted gun with a clean roll of the wrist.

The syringe clicked snugly into the chamber of Skinny’s jigsaw firearm with impossible cooperation, a curious synergy engineered by design. His squared jaw softened, and something like a dance of warm sufficiency seized his witchy black pupils.

If a vagrant spectator in downtown Dearborn were to observe this tiger-banded albino apparition with his scalp of red furze and the burn scarring, he or she might have concluded it an odd tableau when the gaunt figure tracked back down the snow-lustred arch, before mounting a matte-white air rifle on the overpass, and directing its deathly snout at the dogs clamouring for amity beneath him.

Such a witness would recognise that what next eventuated was the waging of some ominous gambit, but he or she would be remiss not to concede that there was an apocalyptic poetry to the light cold scene, as if a final glory rendered by Brueghel before consumption. Snow was lashing the bloodless tousled magnolias shading the intersection, ice veins depraving the convalescing old trees, and two or three wildfowl careening green and scarlet visited the hushed polar sidewalks, a fletch of pheasants who flushed east toward the riverfront. They susurrated and were gone, a rainbow optic in the endless rushing white.

Skinny Dinners did not engage in melancholic reflection, but merely breathed ghosts above the avenue as he augured himself on his haunches. He squirmed momentarily beneath the weight distribution of the gun, adjusting its pennyweight frame, and sighted along the crosshair until it lined up with his quarry. The nut cloves in his mouth were now paste. His nose was wet with mucal ooze, and the hint of a sinus headache spiralled warningly behind his right eye. He blinked thrice in rapid succession, and slackened his triggerhold.

A sudden sadness sprang unbidden in the lean meat of his chest, a mournful resign that swallowed his heart. Skinny Dinners inured himself to a legacy of travesties, bunked down in the raw sorrow that his friends and employers had betrayed his loyalty, incited him into wolfish action, forced his fire-bitten hand. He could see that acid wash alone would lubricate his future, that from here the particulars of his behaviour would be ugly and inhumane.

His knuckles grew empurpled. His earlobes burned a hundred injustices.

Skinny Dinners finally relented to his quashed dog nature: he was yearning to break off the leash, root out every rat. His brow thundered. He pulled the trigger. A shot rang out, a whipcrack of fricative sound sundering the still of the smoking white horizon.

For an eternity no movement followed, the rupture shocking the shrunken world into unvoiced allegation. Echoes surfed the hackles of every dog, terrified and snarling, their bellies peeling across the frozen asphalt. Skinny waited and the whiteness fell, and Skinny waited and the dogs scrambled, and Skinny waited and the snowflakes suffocated the bark of supple green pines like clover, and Skinny waited and the River Rouge curled into the black forge of denuded, decay-eaten Detroit. Skinny remained chest-in-the-snow, and the gun eased back into his armlock, skating against the inside of his forearm, and kinesis was restored to the world, the gunshot disbursed to ever fainter whispers, and a million street dogs retreated snapping, yelping, keening, snarling, into the covert quadrants of the city.

He felt shamed as they wheeled about scattering; he was soul-deep in moral quicksand, invaded by a rank blue funk of self-disgust. He palmed an errant snowflake from his eye.

The dog he’d shot, the freshly-improvised syringe dart sutured in its rising black flank, was slumped in the chum-flooded junction of the emptying avenue, its whimpers reduced to a plosive falsetto coo. Skinny drew his binoculars to his catty gaze, and squinted for definition, for confirmation, through the lens. The dog in question was a soft sable mass on the crosswalk, depleted — at least in this instant — of war and gamble and warm animal terror, no red clapping maw, no ears flattened and back legs scoring furrows in the frost. The intravenous sedative had worked its magic into the black beast’s churning sinewy interior. Skinny understood enough about the science to know that he had whole minutes to act, and if he waited any longer an armoured fleet of cops in blue fatigues was certain to materialise along the sidewalk besides.

He was limited to this opportunity, this sole ploy, this merest distance of yards, now.

He didn’t linger over dismantling the photopolymer air rifle, but merely dispatched the readily assembled firearm into his rucksack, along with the few rubber-stoppered buckets of chum stock remaining, and pocketed the phial of ACP in the armpit of his jacket. He was brisking along the embankment, and then he was navigating the stairs two at a time as they corkscrewed their way back toward the steaming reaches of Michigan Avenue. The satchel rattled against his shoulder, administering an unpleasant coldness to the pale flesh of his neck, but he was springing now, fanging his way toward the bottom while his sneakers of flossy Hoth husbandry avoided assuming impact with the cement for more than the briefest glances. Skinny was virtually lemur-born, such was the impression elicited by his long-limbed agility, because he was so svelte in his movements now that the snow seemed not to catch him, a lithe white star of track and field, a baby-faced harlequin of spidery graces.

He had made it to the foot of the colonnade again, was hustling at street level toward the horsey beast asleep at the snow-bottled intersection, the dog in its soporific muddle of pelt fleece and black fat, a plaintive homily quaking in its throat.

Skinny slowed down to a stroll, his heart craving collapse and his lungs swimming in his chest, and he coasted forward through the debris of gore until he was sidling pussyfooted around his beautiful barrel-sized trophy, its kingly head at rest on its forelegs, eyes half-slack with enigmatic quiet.

The dog was a grizzled male Plott hound, a colt-like giant enthroned in a soapy black coat, an imperious saunter about the eyes, two intelligent garnet facets. He had seas to swim, bears to hunt, moats to besiege. He was Skinny’s great new beloved, a fairytale inamorato the size of a monster Buick. The dog boomed a little more darkly, a little more saxophonic at Skinny’s elegant approach, but it did not wrestle to right itself, merely snorted its shining globular muzzle as the unfamiliar threat announced himself with continued stealth.

The dog watched, its majestic corduroy ears tented in surprise, as the Messiah of Curs retreated a distance of ten feet away before bustling to sit down, squat and attentive, the man’s wine-dappled face an artefact of trusting observation.

The dog and Skinny Dinners sat at a reversed convex angle whole body lengths apart for at least seven minutes. Skinny’s breath softened, assumed distinctly sinuous shapes. The Plott hound cocked its head quizzically, yowled in discomfort, and pawed at the snow where it sprawled. Gradually the dog inched forward in playful prostration, surfing its glossy onyx musculature through the snow, until it was a hand’s breadth away from Skinny and whining mournfully for his ministrations.

The dog’s hot noxious breath blew against his pillowy cold clavicle, and moulded over his bristled dome. Skinny continued maintaining a quarter-mile stare in the opposite direction. The dog was now strafing its moist snout through his hair, exhaling the sweet spiced fetor of loss into the warm splint of his inner ear, but Skinny did not grin again or edify the courtship until the dog dangled its head into his lap, and surrendered to his better wisdom.

Skinny’s fingers sunk into its pelt, jiggered the beast from under the chin. The dog was moaning now, willing his strange benefactor to retrieve the tranquilliser steeled in its hide.

Skinny Dinners cajoled soft promises to the dog, the man’s face buried in its dark marzipan coat, his mouth disclosing a serenade into its nobly sloping ears. There was a smile in his voice, but the dog knew the words the man spoke signified a therapeutic truth.

‘Who’s a good boy? You’re a swell good boy. When we get to where we’re going, I’m gonna name you Ganymede,’ Skinny lullabied, massaging the dog’s ears.

‘Now, Ganymede, what I have to do for you is going to sting like a hoary old hornet in the nutsack. But I can’t leave this needle in your side, you understand? Any longer in you, and there’s danger of a seizure risk or an epileptic complication, you hear me? This thing’s gotta go, and you and I gotta walk, okay?’

The dog understood the articles being negotiated. The man was calm, and kind, and resourceful, and an emissary for future meals — so much food to sweat the throat. The dog knew to subscribe to the man’s rationale was to exercise the most advantageous tactic. Befriending the man would save its life, winch it away from the seething white barbarism of a final winter.

The dog knew what should happen. When the man’s cool soothing hand closed around the haft of the needle, Ganymede thought only of the foliage on the trees enveloping Michigan Avenue as they rustled beneath the snowfall, watched the choke cherries and the aspens, bone white as ivory, submit themselves to the weight of their bitter cloak, and he couldn’t sense there was any other way, no time in all of history for even one defector, one exception — just a rule as old as centuries. Ganymede transferred his own eyes to those rooted high in the kind man’s head, and suddenly the cold, the ancient cold in the thrall of its element, was rushing in, every storm in every century, snaking its way through the interred roots of the magnolias to lance its way through the wound in his flank. The dog howled, its colossal black head thrust back in bright electric throttles of pain, and the earth kept its axial spin, not even slowing in its severe sickled mission to make its demands of everyone before they could even think to fall into line.

The trees bowed, the snow fell.

Some time later the man and his dog set to limping up the highway.

Kirk Marshall (@AttackRetweet) is a Brisbane-born writer and teacher living in Melbourne, Australia. He has written for more than eighty publications, both in Australia and overseas, including "Vol. 1 Brooklyn" (U.S.A.), "Word Riot" (U.S.A.), "3:AM" Magazine (France), "Le Zaporogue" (France/Denmark), "(Short) Fiction Collective" (U.S.A.), "The Vein" (U.S.A.), "Danse Macabre" (U.S.A.), "WHOLE BEAST RAG" (U.S.A.), "Gone Lawn" (U.S.A.), "The Seahorse Rodeo Folk Review" (U.S.A.), "The Journal of Unlikely Entomology" (U.S.A.) and "Kizuna: Fiction for Japan" (Japan). He edits "Red Leaves", the English-language / Japanese bi-lingual literary journal. He now suffers migraines in two languages