Aurelia: A Ballet in Prose (Act 1)

By Sakina B. Fakhri

If you were to happen upon the once-elaborate monastery now in the hills of Northern England, you would find its jagged mass of ruins to be something of an unfinished sketch: The lantern tower at the northwest corner of the grounds is measured by the uneven shadow cast by the presbytery at the eastern end of the expanse, and the cloister, once arcaded in black marble, has eroded to a simple white sandstone. Legends that have since fallen into disrepute speak of a medieval order of lapsed nuns who had taken for their residence this abandoned fortress after having suffered expulsion for their sins by the now extinct Order of Circassia. It was said, though mostly in jest and generally as counter-point to a moralistic tale, that these nuns had danced a knight to his fiery death to secure their safe escape.

The towns and villages that had once sprung around the monastery had died away, and so these lapsed nuns remained upon this vast tract of land, undisturbed, amidst the lush, rolling hills of Yorkshire--flanked on all sides by mountains and forests of farms connected by dusty ochre roads which fell into disuse except, from time to time, by wayward travellers in search of a legendary thing that they only, by dint of their own personal certainty, could have believed to abide there.

The nuns were believed to have harnessed rare alchemical powers as their path to the divine; by transmuting the four elements and maintaining their delicate balance, they were able to bring the interactions of matter to their purest and most perfect synthesis—they transformed, thus, plainness into a most innate beauty and malady into instinctive percipience; they released the nature of each existing thing into an atmosphere in which it could breathe. Their fervor, in this respect, had been of detriment to the sacrosanct humility of the Order and an embarrassment to their abbess, and so it was that the band of offending nuns was expelled by swift and incontrovertible Papal decree. Their powers, though dubious, were famed, and they were beset by constant marauders who believed their magics to lie in their physical accoutrements; several hundred miles from their abbey, they were cornered by a knight in a graveyard who sought to divest them of their talisman. But he was a fool—their power no more resided in their talisman than a conductor’s resides in her baton—for it is the gestures themselves, and not the wand, that prompt the stirrings of a vast orchestra. So, to protect their secrecy as they stole away in the night, these nuns crowded the knight in their flowing white robes and left him flailing amidst the gravestones, their habits cast into the air where they settled amongst the tombstones like ghosts in the moonlight. Thus obscured to the knight, they continued along their way, their long hair now fallen upon their shoulders and the wind casting its gaze upon their necks.

Every so often, the legend—spread most vastly by skeptics—fell upon ears that saw in this slip of a tongue a possibility for escape, and so it was that, from time to time, these nuns were applied to for succor by the desperate and strong-willed from towns all over England. The nuns would adjust the vibrations of the elements so that they vibrated in tune with the person—water that passed the gullet with the burn of fire, they would not adjust the fire, but the throat; for those who felt they breathed through earth or walked upon air, they would make the earth a thing that could be breathed, the air a thing to be trodden upon. It was thus that they respected the proclivities of the individuals to their elements; that they made the earth rise for those who needed it so, made it dissolve for those who could not abide by it. Some believed the nuns could drink fire, and be sustained.

The makeshift pilgrims who sought this deliverance imbibed the idea of this pleasant fiction and, in the certainty of their own belief, chose this legendary landscape over an identifiably undesireable reality. As such, these iconoclastic nuns of the Order of Circassia could boast a unique collection of headstrong sojourners who had joined their ranks. The nuns, having brought very few menfolk to their escape, had few children to birth, and thereby the Order was condemned to the life span of only a few generations.

Now the monastery is inhabited by no one; but the sun shines upon it all the same with nothing extraneous to absorb its light except for the hand-crafted bricks that once supported the heavy Romanesque archways. The pink-yellow brown glimmers against the moss that still grows; and there are the ancestors of the Swainson’s thrush, gray birds that seem to materialize from a gust of wind, and from the monastery can be seen the upswirl of thousands of birds that animate at once from all the windows and the archways and the parapets and the chimneys, as though the monastery were a giant flute expelling its melody in the form of swirling birds.

The vast expanse of its grounds remain covered in verdant grasslands, rolling hills, and mossy vines still cling to the maze-like walls of this once-fortress. The monastery has made no significant impression on the academic world beyond the discovery of a few choice pieces - wooden bowls with mysterious staining, a decrepit lyre with two strings still intact (B and F), and written notes detailing the medical conditions of those who had travelled to the nuns for succor. But beyond even this, there is a residue of this hidden era that persists all throughout Europe and through the world; an idea forged here without its inhabitants recognizing it as such, they perceiving it only in the form of a young woman come to their door with a strange request. She is Aurelia.

***

On the night before she undertook her journey, Aurelia regarded the skyscape of London one last time from atop the turret balcony of her bedchamber. A full moon illuminated a thick penumbra of clouds that scattered the light, rendering the sky a shade of darkened ultramarine, and the sky appeared, as the skin of an old woman’s face, stretched with age. A white light was apparent in delicate adumbrations, as though it were wisdom that shone through the cracks.

And so Aurelia looked upon a city of Norman spires daubed in azurite; the heads of criminals were arranged haphazardly on spikes atop the gatehouse of the Southwark Cathedral. The stillness of the Thames was marred insignificantly by the steady moorings of a single cog, visible only by the slight folding of its mast sail, and she tracked its movement and thought that if she looked upon this, if she gazed upon only this--the movement of it as a single point--then there might be some deliverance from the tyranny of lines and angles, the persistence of curves.

Aurelia imagined the arduous path that would take her into the hills of Yorkshire far beyond the borders of the city. The wails of the mad enthroned within the local confines of the Royal Hospital of St. Bartholomew’s rose into the night like the wails of Gregorian chanters, and she saw these thoughts rising in cloudy tufts and abutting the dome from underneath; their desperation, so unavailingly human, sought outlet in the bay windows of the upper embankments. The howls rose like threads in the night and twisted about the city, running along the castle walls and down the city streets. Something had come loose in the city’s nighttime--visible to a single cog that set out on its nighttime voyage to trade its wares across the Thames--and these mad thoughts, imprisoned in the daytime within the walls of the monastery, were allowed play to outline the cityscape. They travelled in arabesques over the cathedrals and danced alongside the London Bridge, smudged out the heads of criminals and instead floated upon the water, surging towards the sky with virtuosic dignity and a formidable grace. It was beautiful for a moment; but then it was all afire--or so it seemed, as Aurelia wrapped her shawl about her shoulders and made her way secretly to the stables, where she was offered by the stable boy the release of her Suffolk mare.

***

Aurelia saw the map of her course as though from above, weaving throughout the countryside and its multifarious terrain; she knew it for no reason in particular except for that the movements of the unshorn path seemed to her the intricate footwork of a single body, swaying and twirling upon a stage that grew light and dark in intervals. Like this, days passed, and

Aurelia and her horse had followed the River Skell to its thinnest point along the Yorkshire Highlands.

Aurelia was more adept than any other at the maneuvering of her mare, for she understood the ways that the muscles and sinews of a horse made it move, and she calibrated the forces and angles of her own limbs into its perfect synchronicity, being almost uncomfortably aware of the new balance struck between the human machinery and the equine, second by second, as hundreds of lines and angles reconstituted with a burst of force to re-acquaint with the terrain, and to take again as if to the skies. It was said that Aurelia could perform powerful and elegant feats by horse that very few had learned to master--and of those, only soldiers, and that for the purposes of war.

The hours of sunlight were the most taxing; the world was bared in its extraordinary array, and this saturated canvas struggled thus against the plane of the imagination. Aurelia clasped her forehead and led her mare to rest for a moment upon the sloping embankment of the river.

The noonday sun illuminated a pathway—invisible by night—that cross-stepped up the side of the mountain. From this distance it looked generally unpromising to the casual traveller—a wayward hair fallen from some divinity’s careless tress, liable to change its orientation at any moment. For Aurelia, the challenge of precipitous height offered relief from the monotonous meanderings of the river stream; from above would be visible not the one path along the river, but many, and the promise of this stultified the laggard boredom that had begun to thicken in Aurelia’s chest like a viscous mist. But now, so close to the river journey’s end, she took a special pleasure in observing her horse lapping up the water, which seemed to echo across the green brush that dotted the bare cliffs. Cruel, the sparseness of the vegetation gave the impression of limited verdure in the valley beyond the peak, and yet Aurelia was certain that her destination would be quietly lush; that there were nuns fluttering to and fro and that there lived beyond the hill a fabled community, boisterously flourishing in its own regard. She did not hazard to think that what she was looking for did not exist beyond the cliff.

“Hallo,” an approaching pilgrim in a broad-brimmed hat took Aurelia by surprise. He donned the clothes of a wealthy man but appeared in his manner to be a glorified peasant; and in fact the broad-brimmed hat seemed to have been obtained from one travail and the robe, not in the least part of a set, from some discarded raiment of a passing nobleman. Aurelia eyed him dubiously, for he did not resemble the pilgrims with whom she was familiar, and he seemed, by all counts, to be travelling by himself. She quietly hid her satchel beneath the folds of her olive-green dress; in this was her betrothal ring, measured in gold and thinned into the shape of two hands that clasped one another; she had thought that if she came to some trouble she might sell it, or if she were captured by marauders she would exchange it for her release.

The pilgrim furnished an amulet in Aurelia’s direction, frightening her as she sat upon the grass pulling stalks from the bank of the river. The amulet was a silver medallion upon a striated link chain, which he pushed invasively into Aurelia’s line of sight. She considered the image of the engraved saint, leaning upon a tired scavein with his back hunched horizontally.Then, she pushed the amulet towards the traveller, who pocketed it again in the leather scrip that hung from his waistband.

“Just by way of explanation,” he admitted. “I don’t mean to cause you any fright. Perhaps you could make use of a companion on your journey.” He furnished again the amulet by way of corroboration, “By the grace of St. Christopher.”

“I am fine on my own, thank you,” Aurelia responded with a kindness more earnest than manners often allow.

She had hoped the traveller would immediately take his leave upon this rebuff, but he set himself up a curious station upon the bank of this river, putting out all his curios along the boulder. He bent down and regarded their shadows, seeming to measure something, and then scratched his chin. His beard moved from side to side, casting a full shadow upon his array and then revealing it in violent gusts of light. “Mmm, mmm…” he murmured to himself with every measurement as he moved these from side to side, seeming alarmed at the effect his own shadow had upon the piece. He then took to cleaning himself in the river, as this army of curious he had lined up stood as sentinels on the watch.

“Where are y’going to?” he called from the river when he seemed refreshed enough to have gathered his bearings. Now his locks glittered in the sunlight and Aurelia imagined that he was a statue come to life. “From your clothes, you don’t look to be in a solitary way,” he said.

“I am ill.”

“All the more reason you should command accompaniment.”

“It is not that sort of illness. If I had stayed—if I had made it known to anybody—it would be my lot to be consigned forever to a life within the walls of St. Bartholomew’s.”

The traveller now dried himself off, stray specks of water dotting the boulder as he shook his locks. His curios flinched as they maintained their hallowed posts. He swept them up into his satchel and they felt again to be irredeemably inanimate as they clicked together and he tightened the cord.

“I wish you good fortune and solace,” the traveller said, tipping his hat, and thus the stranger went whistling upon his way.

Later, Aurelia would think upon this as she lay in her monastery quarters and wonder, as the constellations played themselves out above her head, where the traveller might have gone to and whether he bathed always with his curios all settled into rows or whether it had been a chance occurrence, shared by them both, upon the River Skell.

***

She felt inside of her the drum of her circulation, along the journey, as she felt herself either closer to or farther from her goal - this reaching a high pitch at those moments when she wondered at the existence of the monastery at all - but as Aurelia and her mare turned the last hill, she saw the grounds of the monastery nestled within the hills - as though the world held it between its index and its forefinger and held it up to the light for examination. She wondered for a moment whether merely having believed it caused it to appear at this moment instead of any other; she wanted to believe that this is how it must work, and that really this monastery could have appeared anywhere in this infinitely malleable universe, and that a triumph more emotional than physical, more personal than situational, caused it to appear before her now; that this was how the mare, who could not possibly have known his destination, blazed his weary tread into a steady trot and made its way steadily down the sinuous path towards the edifice, knowing that that was the place where they had been heading.

The monastery was the residue of ruins and reconstructions, a temporal patchwork of sorts: three fortress walls that indefatigably beg a fourth; grass sprung from where once the monks of the Order of Albigensia walked along the marble corridors on the balls of their feet; a burbling moat--emitting constantly a sound as of numerous butterflies batting their thousand wings--that must have burbled so even as it commingled with the echoing boom of a young soldier’s blunderbuss--fired for the very first time. Following this ravaging military conflict, the grass grew verdant upon the embankments and the weeds gave way to bright moss that glittered green even in the moonlight. Our story, however, is not that of the war that ironically brought these young defectors to their knees, nor is it that of the Order of Albigensia and its systematic demise. After the abandonment of the grounds in the 11th Century by the soldiers at the Battle of Hastings; after the subsequent raids by the Norman invaders; after the adoption by and dissolution of the Order of Albigensian monks, Aurelia had come to call upon the nuns who were the sole inhabitants of these grounds, and she found that it was no boisterous compound; no flourishing village.

As Aurelia wound her way through the final foothills and descended upon the entrance to the monastery, the sun shone upon representations of Apollo and Mercury were integrated into the engravings that appeared both on the facade and in the main corridor. The image of the lyre, of which it is said that Mercury created one morning and learned to play by noon, was seen everywhere. Upon the tympanum, Mercury stood at the center with his winged sandals and his winged hat, leaning upon his caduceus, Jupiter’s stolen thunderbolt burning in his left hand. Along the supports of the archway was a representation of Mercury plucking the four strings of a lyre to angels that floated in mid-air, in stone relief; the sculptural tufts of a bird flapped in accordance with the melody, a broken string of the lyre in its beak. Aurelia thought of the stone bird and wondered if perhaps her heart skipping a beat was concomitant with a bird falling somewhere. With each pluck of the lyre, one of the four humors was struck; this could affect one greatly.

Aurelia knocked on the heavy wooden door, flanked on either side by imposing Romanesque figures who must have been the donors to the monastery in its original incarnation. The figure on the right held an unfurling scroll; the figure on the left looked at her crossly.

“The carvings were once vermilion,” Aurelia told the nuns when they answered her call at the door, though she had no way of knowing so, “and the image of the lyre was painted in bronze.” She collapsed at the doorway; a thrush landed upon her hair, which was splayed over the stone step. Groups of these thrushes swept from the parapets, and it appeared as though the edges of the roof disintegrated into the blue sky.

***

It was not immediately that the nuns had agreed to grant Aurelia’s request - they bade her stay with them for a full week until she had reached full physical recovery from her journey and could be deemed of sound mental state to decide her own affairs. The nuns left Aurelia free, for the most part, to wander the grounds as she wished. They noticed that she came to be more and more laggard in the daylight, but as night fell, and she was free to wander in only the punctuated darkness of her own candle, her vision became more manageable by her and she was calmer.

The original band of individuals who constructed the monastery were believers of the Manichaean philosophy, and indeed many of the architectural components of the monastery reflect the particulars of this creed of darkness and light. Some corners are kept dark, intentionally unilluminated, but just because it is never seen does not mean it is considered “wasted”; other spots experience light or darkness according to the time of day, so the building has not experienced a repetitive moment but has instead been recreated in infinite visual iterations delineated by the shifting light. Light is either radiated unabashedly, pervasively by the sun, abstractly spreading throughout, or it is a concentrated, viscous thing from a candle that chooses what to make material.

Beside her bed they placed a small wooden box for her meager belongings, painted—only on the inside—a Venetian red. Aurelia recalled that the goldsmith had measured perfectly its weight, rolling the fragile suspension between his two fingers and pointing the others straight ahead until the two bronze scale plates reached a stasis; she had held her breath, without knowing she was doing so, until the pendulum had come to a stop. In the moments when she felt at peace in the monastery, she would forget for a moment why she had escaped, and would hold this ring and weep for her family, for the man to whom she was to be betrothed, to the stable hand who had so innocently unlocked the mare for her that night. But then she would remember the visions that plagued her and she would hear the cries of St. Bartholomew’s again, blotting out the stars.

The monastery was designed specifically according to the interaction of the constellations with Pythagorean/Platonic cosmic numerical theories, and openings in the roofs corresponded to the movements of the stars in particular seasons. Later, those in the court of Catherine d’Medici would dance according to the configurations by which this monastery admitted starlight.

Aurelia’s bedchamber was open to the sky, and at night she would calculate the movements of the constellations; stepping with her feet upon the stars, one by one, in the patterns that they carved out and the subtle variations that they mapped. She had followed the stars since she had been a child, had slept on the balcony when the weather allowed, rested her head on her shawl as she calculated the number of boats on the Thames by the mere sound of the water and imagined a ship cutting its movements through the stars, transferring wares from this port to that one. She carried a compendium of these constellations in her heart and felt that each day she weaved another string held together by beads of starlight, a brocade of sorts, wrapped gently around her heart; that she would lay them out, each string a timeline of stars of various provenance, unfurl them from herself and they would wind and branch over the city of London and then she would walk upon paths of her own starlit veins. She would dance upon the streams of constellations, glide as through rivers, her feet barely touching - lifted by light only, dancing through air. At times, it would seem as though she flew.

***

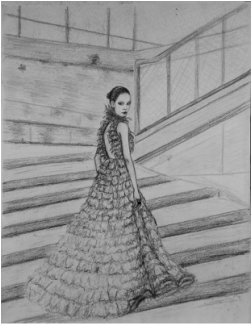

At last, the nuns agreed to assess Aurelia’s request. Each night for seven nights, a different nun would sit at Aurelia’s bedside and hear of her illness: She had become increasingly plagued with visions of lines and angles that recoordinated and reconstituted any landscape in front of her; she could not set her eyes upon the sloping roofs of the palace without feeling an uncontrollable ache in her spine, could not look upon the creases in her lover’s face without calculating the aerial velocity of an extended line and balance. Seeing these lines everywhere she looked, she imagined a beautiful confluence - so much so that she was glutted with it, day by day, and without outlet.

These notes were recorded comprehensively - religiously - and following the seventh night and a secret conference of the nuns, the last session was conducted. Aurelia’s words had filled three books. The nuns deemed her worthy of the recompense for her suffering, and indeed, that evening, as sunset approached and Aurelia saw the last hint of daylight she was ever to see, the nun brought a gold mazer filled with arsenic; first, she bade Aurelia wash her hands in the bowl and recite an oath; then, with the acid, the nun blotted out the girl’s eyes.

This nun lit the candle by Aurelia’s bed as she left; the stars had grown blurry in their physical incarnations, though Aurelia still retained of them the encyclopedic memory she had honed for a lifetime. “It will take several hours,” the nun said, “before the blindness overcomes you - you will find in it just compensation, and eventual peace.”

“I hear bells,” Aurelia told her, “And I imagine that I am in a garden of high stone walls.”

“There are no bells here, dear,” the nun said. “They have ceased long ago; we have not bothered to tend to the disrepair, there being so few people here to hear them.”

Aurelia thought of human figures that could move like flames; that a flame might bring a limestone caricature to life. And in her mind, in the light cast by the flame, she saw around the room a thousand moments that passed in a flash of shadow play along the walls. They say that once a man tried to keep the memory of his departed lover by outlining the shadow where she last stood. But alas, he failed not in respecting a shadow but in trusting an outline; it was not her in her essence, for she did not move. Now, upon the walls of Aurelia’s chambers, a shadow of a dancer takes her mask off for the first time and the audience whom she has always seen can now see her; the King of France hears of the storming of the Bastille through a whisper, as he sits in his stage balcony, and the tragedy being played out in front of him takes on a morbid sheen; in indoor circus in Russia sees its elephants replaced by heirs and heiresses, whose earrings twinkle as they clap; and, during the performance of her career, a ballerina falls into an open grave as the nuns dance in her wake…

The heartbeat, as they say, is the stamping of the feet, and breathing is the hint of the melodic phrase. As Apollo the sun god banishes the horrors of night and heralds the dawn, the shadows on the wall fade to the ochre. Aurelia does not wake up.

The notes on Aurelia’s condition, of no use to the nuns any longer, are deposited in a dark corner of the monastery and remained there untouched for nearly a hundred years. These are to be found a century later by traveling marauders and sold at the time of the Renaissance to the throne of Italy, which is to be the first site of the ballet--of which the record of Aurelia’s illness is to be the first formal treatise.

***

The birds near the monastery now spread throughout the grounds as starlings, sweeping upwards in a unified gale and then scattering like dark dust upon the fortress turrets. They mirror the scattering of the pigeons at Trafalgar, which seems a far way off, and suggest the scattering of grains that served as Beauchamp’s inspiration for the choreography of his ballet. These birds travel continents easily (if not quickly) and have been known to be the cause of exotic seeds that have been transported and planted as far as North America. These grains came to be traded at high value in the late 18th century on the trading floor at Wall Street, before it was the machine-driven thoroughfare it is now - when it was in fact a trading post for farmers toting bags of grain.

An apple tree now hangs above Aurelia’s grave; the Swainson’s thrush plays with the stalks of grass that move to and fro to the beats of the starlight upon her headstone.

The towns and villages that had once sprung around the monastery had died away, and so these lapsed nuns remained upon this vast tract of land, undisturbed, amidst the lush, rolling hills of Yorkshire--flanked on all sides by mountains and forests of farms connected by dusty ochre roads which fell into disuse except, from time to time, by wayward travellers in search of a legendary thing that they only, by dint of their own personal certainty, could have believed to abide there.

The nuns were believed to have harnessed rare alchemical powers as their path to the divine; by transmuting the four elements and maintaining their delicate balance, they were able to bring the interactions of matter to their purest and most perfect synthesis—they transformed, thus, plainness into a most innate beauty and malady into instinctive percipience; they released the nature of each existing thing into an atmosphere in which it could breathe. Their fervor, in this respect, had been of detriment to the sacrosanct humility of the Order and an embarrassment to their abbess, and so it was that the band of offending nuns was expelled by swift and incontrovertible Papal decree. Their powers, though dubious, were famed, and they were beset by constant marauders who believed their magics to lie in their physical accoutrements; several hundred miles from their abbey, they were cornered by a knight in a graveyard who sought to divest them of their talisman. But he was a fool—their power no more resided in their talisman than a conductor’s resides in her baton—for it is the gestures themselves, and not the wand, that prompt the stirrings of a vast orchestra. So, to protect their secrecy as they stole away in the night, these nuns crowded the knight in their flowing white robes and left him flailing amidst the gravestones, their habits cast into the air where they settled amongst the tombstones like ghosts in the moonlight. Thus obscured to the knight, they continued along their way, their long hair now fallen upon their shoulders and the wind casting its gaze upon their necks.

Every so often, the legend—spread most vastly by skeptics—fell upon ears that saw in this slip of a tongue a possibility for escape, and so it was that, from time to time, these nuns were applied to for succor by the desperate and strong-willed from towns all over England. The nuns would adjust the vibrations of the elements so that they vibrated in tune with the person—water that passed the gullet with the burn of fire, they would not adjust the fire, but the throat; for those who felt they breathed through earth or walked upon air, they would make the earth a thing that could be breathed, the air a thing to be trodden upon. It was thus that they respected the proclivities of the individuals to their elements; that they made the earth rise for those who needed it so, made it dissolve for those who could not abide by it. Some believed the nuns could drink fire, and be sustained.

The makeshift pilgrims who sought this deliverance imbibed the idea of this pleasant fiction and, in the certainty of their own belief, chose this legendary landscape over an identifiably undesireable reality. As such, these iconoclastic nuns of the Order of Circassia could boast a unique collection of headstrong sojourners who had joined their ranks. The nuns, having brought very few menfolk to their escape, had few children to birth, and thereby the Order was condemned to the life span of only a few generations.

Now the monastery is inhabited by no one; but the sun shines upon it all the same with nothing extraneous to absorb its light except for the hand-crafted bricks that once supported the heavy Romanesque archways. The pink-yellow brown glimmers against the moss that still grows; and there are the ancestors of the Swainson’s thrush, gray birds that seem to materialize from a gust of wind, and from the monastery can be seen the upswirl of thousands of birds that animate at once from all the windows and the archways and the parapets and the chimneys, as though the monastery were a giant flute expelling its melody in the form of swirling birds.

The vast expanse of its grounds remain covered in verdant grasslands, rolling hills, and mossy vines still cling to the maze-like walls of this once-fortress. The monastery has made no significant impression on the academic world beyond the discovery of a few choice pieces - wooden bowls with mysterious staining, a decrepit lyre with two strings still intact (B and F), and written notes detailing the medical conditions of those who had travelled to the nuns for succor. But beyond even this, there is a residue of this hidden era that persists all throughout Europe and through the world; an idea forged here without its inhabitants recognizing it as such, they perceiving it only in the form of a young woman come to their door with a strange request. She is Aurelia.

***

On the night before she undertook her journey, Aurelia regarded the skyscape of London one last time from atop the turret balcony of her bedchamber. A full moon illuminated a thick penumbra of clouds that scattered the light, rendering the sky a shade of darkened ultramarine, and the sky appeared, as the skin of an old woman’s face, stretched with age. A white light was apparent in delicate adumbrations, as though it were wisdom that shone through the cracks.

And so Aurelia looked upon a city of Norman spires daubed in azurite; the heads of criminals were arranged haphazardly on spikes atop the gatehouse of the Southwark Cathedral. The stillness of the Thames was marred insignificantly by the steady moorings of a single cog, visible only by the slight folding of its mast sail, and she tracked its movement and thought that if she looked upon this, if she gazed upon only this--the movement of it as a single point--then there might be some deliverance from the tyranny of lines and angles, the persistence of curves.

Aurelia imagined the arduous path that would take her into the hills of Yorkshire far beyond the borders of the city. The wails of the mad enthroned within the local confines of the Royal Hospital of St. Bartholomew’s rose into the night like the wails of Gregorian chanters, and she saw these thoughts rising in cloudy tufts and abutting the dome from underneath; their desperation, so unavailingly human, sought outlet in the bay windows of the upper embankments. The howls rose like threads in the night and twisted about the city, running along the castle walls and down the city streets. Something had come loose in the city’s nighttime--visible to a single cog that set out on its nighttime voyage to trade its wares across the Thames--and these mad thoughts, imprisoned in the daytime within the walls of the monastery, were allowed play to outline the cityscape. They travelled in arabesques over the cathedrals and danced alongside the London Bridge, smudged out the heads of criminals and instead floated upon the water, surging towards the sky with virtuosic dignity and a formidable grace. It was beautiful for a moment; but then it was all afire--or so it seemed, as Aurelia wrapped her shawl about her shoulders and made her way secretly to the stables, where she was offered by the stable boy the release of her Suffolk mare.

***

Aurelia saw the map of her course as though from above, weaving throughout the countryside and its multifarious terrain; she knew it for no reason in particular except for that the movements of the unshorn path seemed to her the intricate footwork of a single body, swaying and twirling upon a stage that grew light and dark in intervals. Like this, days passed, and

Aurelia and her horse had followed the River Skell to its thinnest point along the Yorkshire Highlands.

Aurelia was more adept than any other at the maneuvering of her mare, for she understood the ways that the muscles and sinews of a horse made it move, and she calibrated the forces and angles of her own limbs into its perfect synchronicity, being almost uncomfortably aware of the new balance struck between the human machinery and the equine, second by second, as hundreds of lines and angles reconstituted with a burst of force to re-acquaint with the terrain, and to take again as if to the skies. It was said that Aurelia could perform powerful and elegant feats by horse that very few had learned to master--and of those, only soldiers, and that for the purposes of war.

The hours of sunlight were the most taxing; the world was bared in its extraordinary array, and this saturated canvas struggled thus against the plane of the imagination. Aurelia clasped her forehead and led her mare to rest for a moment upon the sloping embankment of the river.

The noonday sun illuminated a pathway—invisible by night—that cross-stepped up the side of the mountain. From this distance it looked generally unpromising to the casual traveller—a wayward hair fallen from some divinity’s careless tress, liable to change its orientation at any moment. For Aurelia, the challenge of precipitous height offered relief from the monotonous meanderings of the river stream; from above would be visible not the one path along the river, but many, and the promise of this stultified the laggard boredom that had begun to thicken in Aurelia’s chest like a viscous mist. But now, so close to the river journey’s end, she took a special pleasure in observing her horse lapping up the water, which seemed to echo across the green brush that dotted the bare cliffs. Cruel, the sparseness of the vegetation gave the impression of limited verdure in the valley beyond the peak, and yet Aurelia was certain that her destination would be quietly lush; that there were nuns fluttering to and fro and that there lived beyond the hill a fabled community, boisterously flourishing in its own regard. She did not hazard to think that what she was looking for did not exist beyond the cliff.

“Hallo,” an approaching pilgrim in a broad-brimmed hat took Aurelia by surprise. He donned the clothes of a wealthy man but appeared in his manner to be a glorified peasant; and in fact the broad-brimmed hat seemed to have been obtained from one travail and the robe, not in the least part of a set, from some discarded raiment of a passing nobleman. Aurelia eyed him dubiously, for he did not resemble the pilgrims with whom she was familiar, and he seemed, by all counts, to be travelling by himself. She quietly hid her satchel beneath the folds of her olive-green dress; in this was her betrothal ring, measured in gold and thinned into the shape of two hands that clasped one another; she had thought that if she came to some trouble she might sell it, or if she were captured by marauders she would exchange it for her release.

The pilgrim furnished an amulet in Aurelia’s direction, frightening her as she sat upon the grass pulling stalks from the bank of the river. The amulet was a silver medallion upon a striated link chain, which he pushed invasively into Aurelia’s line of sight. She considered the image of the engraved saint, leaning upon a tired scavein with his back hunched horizontally.Then, she pushed the amulet towards the traveller, who pocketed it again in the leather scrip that hung from his waistband.

“Just by way of explanation,” he admitted. “I don’t mean to cause you any fright. Perhaps you could make use of a companion on your journey.” He furnished again the amulet by way of corroboration, “By the grace of St. Christopher.”

“I am fine on my own, thank you,” Aurelia responded with a kindness more earnest than manners often allow.

She had hoped the traveller would immediately take his leave upon this rebuff, but he set himself up a curious station upon the bank of this river, putting out all his curios along the boulder. He bent down and regarded their shadows, seeming to measure something, and then scratched his chin. His beard moved from side to side, casting a full shadow upon his array and then revealing it in violent gusts of light. “Mmm, mmm…” he murmured to himself with every measurement as he moved these from side to side, seeming alarmed at the effect his own shadow had upon the piece. He then took to cleaning himself in the river, as this army of curious he had lined up stood as sentinels on the watch.

“Where are y’going to?” he called from the river when he seemed refreshed enough to have gathered his bearings. Now his locks glittered in the sunlight and Aurelia imagined that he was a statue come to life. “From your clothes, you don’t look to be in a solitary way,” he said.

“I am ill.”

“All the more reason you should command accompaniment.”

“It is not that sort of illness. If I had stayed—if I had made it known to anybody—it would be my lot to be consigned forever to a life within the walls of St. Bartholomew’s.”

The traveller now dried himself off, stray specks of water dotting the boulder as he shook his locks. His curios flinched as they maintained their hallowed posts. He swept them up into his satchel and they felt again to be irredeemably inanimate as they clicked together and he tightened the cord.

“I wish you good fortune and solace,” the traveller said, tipping his hat, and thus the stranger went whistling upon his way.

Later, Aurelia would think upon this as she lay in her monastery quarters and wonder, as the constellations played themselves out above her head, where the traveller might have gone to and whether he bathed always with his curios all settled into rows or whether it had been a chance occurrence, shared by them both, upon the River Skell.

***

She felt inside of her the drum of her circulation, along the journey, as she felt herself either closer to or farther from her goal - this reaching a high pitch at those moments when she wondered at the existence of the monastery at all - but as Aurelia and her mare turned the last hill, she saw the grounds of the monastery nestled within the hills - as though the world held it between its index and its forefinger and held it up to the light for examination. She wondered for a moment whether merely having believed it caused it to appear at this moment instead of any other; she wanted to believe that this is how it must work, and that really this monastery could have appeared anywhere in this infinitely malleable universe, and that a triumph more emotional than physical, more personal than situational, caused it to appear before her now; that this was how the mare, who could not possibly have known his destination, blazed his weary tread into a steady trot and made its way steadily down the sinuous path towards the edifice, knowing that that was the place where they had been heading.

The monastery was the residue of ruins and reconstructions, a temporal patchwork of sorts: three fortress walls that indefatigably beg a fourth; grass sprung from where once the monks of the Order of Albigensia walked along the marble corridors on the balls of their feet; a burbling moat--emitting constantly a sound as of numerous butterflies batting their thousand wings--that must have burbled so even as it commingled with the echoing boom of a young soldier’s blunderbuss--fired for the very first time. Following this ravaging military conflict, the grass grew verdant upon the embankments and the weeds gave way to bright moss that glittered green even in the moonlight. Our story, however, is not that of the war that ironically brought these young defectors to their knees, nor is it that of the Order of Albigensia and its systematic demise. After the abandonment of the grounds in the 11th Century by the soldiers at the Battle of Hastings; after the subsequent raids by the Norman invaders; after the adoption by and dissolution of the Order of Albigensian monks, Aurelia had come to call upon the nuns who were the sole inhabitants of these grounds, and she found that it was no boisterous compound; no flourishing village.

As Aurelia wound her way through the final foothills and descended upon the entrance to the monastery, the sun shone upon representations of Apollo and Mercury were integrated into the engravings that appeared both on the facade and in the main corridor. The image of the lyre, of which it is said that Mercury created one morning and learned to play by noon, was seen everywhere. Upon the tympanum, Mercury stood at the center with his winged sandals and his winged hat, leaning upon his caduceus, Jupiter’s stolen thunderbolt burning in his left hand. Along the supports of the archway was a representation of Mercury plucking the four strings of a lyre to angels that floated in mid-air, in stone relief; the sculptural tufts of a bird flapped in accordance with the melody, a broken string of the lyre in its beak. Aurelia thought of the stone bird and wondered if perhaps her heart skipping a beat was concomitant with a bird falling somewhere. With each pluck of the lyre, one of the four humors was struck; this could affect one greatly.

Aurelia knocked on the heavy wooden door, flanked on either side by imposing Romanesque figures who must have been the donors to the monastery in its original incarnation. The figure on the right held an unfurling scroll; the figure on the left looked at her crossly.

“The carvings were once vermilion,” Aurelia told the nuns when they answered her call at the door, though she had no way of knowing so, “and the image of the lyre was painted in bronze.” She collapsed at the doorway; a thrush landed upon her hair, which was splayed over the stone step. Groups of these thrushes swept from the parapets, and it appeared as though the edges of the roof disintegrated into the blue sky.

***

It was not immediately that the nuns had agreed to grant Aurelia’s request - they bade her stay with them for a full week until she had reached full physical recovery from her journey and could be deemed of sound mental state to decide her own affairs. The nuns left Aurelia free, for the most part, to wander the grounds as she wished. They noticed that she came to be more and more laggard in the daylight, but as night fell, and she was free to wander in only the punctuated darkness of her own candle, her vision became more manageable by her and she was calmer.

The original band of individuals who constructed the monastery were believers of the Manichaean philosophy, and indeed many of the architectural components of the monastery reflect the particulars of this creed of darkness and light. Some corners are kept dark, intentionally unilluminated, but just because it is never seen does not mean it is considered “wasted”; other spots experience light or darkness according to the time of day, so the building has not experienced a repetitive moment but has instead been recreated in infinite visual iterations delineated by the shifting light. Light is either radiated unabashedly, pervasively by the sun, abstractly spreading throughout, or it is a concentrated, viscous thing from a candle that chooses what to make material.

Beside her bed they placed a small wooden box for her meager belongings, painted—only on the inside—a Venetian red. Aurelia recalled that the goldsmith had measured perfectly its weight, rolling the fragile suspension between his two fingers and pointing the others straight ahead until the two bronze scale plates reached a stasis; she had held her breath, without knowing she was doing so, until the pendulum had come to a stop. In the moments when she felt at peace in the monastery, she would forget for a moment why she had escaped, and would hold this ring and weep for her family, for the man to whom she was to be betrothed, to the stable hand who had so innocently unlocked the mare for her that night. But then she would remember the visions that plagued her and she would hear the cries of St. Bartholomew’s again, blotting out the stars.

The monastery was designed specifically according to the interaction of the constellations with Pythagorean/Platonic cosmic numerical theories, and openings in the roofs corresponded to the movements of the stars in particular seasons. Later, those in the court of Catherine d’Medici would dance according to the configurations by which this monastery admitted starlight.

Aurelia’s bedchamber was open to the sky, and at night she would calculate the movements of the constellations; stepping with her feet upon the stars, one by one, in the patterns that they carved out and the subtle variations that they mapped. She had followed the stars since she had been a child, had slept on the balcony when the weather allowed, rested her head on her shawl as she calculated the number of boats on the Thames by the mere sound of the water and imagined a ship cutting its movements through the stars, transferring wares from this port to that one. She carried a compendium of these constellations in her heart and felt that each day she weaved another string held together by beads of starlight, a brocade of sorts, wrapped gently around her heart; that she would lay them out, each string a timeline of stars of various provenance, unfurl them from herself and they would wind and branch over the city of London and then she would walk upon paths of her own starlit veins. She would dance upon the streams of constellations, glide as through rivers, her feet barely touching - lifted by light only, dancing through air. At times, it would seem as though she flew.

***

At last, the nuns agreed to assess Aurelia’s request. Each night for seven nights, a different nun would sit at Aurelia’s bedside and hear of her illness: She had become increasingly plagued with visions of lines and angles that recoordinated and reconstituted any landscape in front of her; she could not set her eyes upon the sloping roofs of the palace without feeling an uncontrollable ache in her spine, could not look upon the creases in her lover’s face without calculating the aerial velocity of an extended line and balance. Seeing these lines everywhere she looked, she imagined a beautiful confluence - so much so that she was glutted with it, day by day, and without outlet.

These notes were recorded comprehensively - religiously - and following the seventh night and a secret conference of the nuns, the last session was conducted. Aurelia’s words had filled three books. The nuns deemed her worthy of the recompense for her suffering, and indeed, that evening, as sunset approached and Aurelia saw the last hint of daylight she was ever to see, the nun brought a gold mazer filled with arsenic; first, she bade Aurelia wash her hands in the bowl and recite an oath; then, with the acid, the nun blotted out the girl’s eyes.

This nun lit the candle by Aurelia’s bed as she left; the stars had grown blurry in their physical incarnations, though Aurelia still retained of them the encyclopedic memory she had honed for a lifetime. “It will take several hours,” the nun said, “before the blindness overcomes you - you will find in it just compensation, and eventual peace.”

“I hear bells,” Aurelia told her, “And I imagine that I am in a garden of high stone walls.”

“There are no bells here, dear,” the nun said. “They have ceased long ago; we have not bothered to tend to the disrepair, there being so few people here to hear them.”

Aurelia thought of human figures that could move like flames; that a flame might bring a limestone caricature to life. And in her mind, in the light cast by the flame, she saw around the room a thousand moments that passed in a flash of shadow play along the walls. They say that once a man tried to keep the memory of his departed lover by outlining the shadow where she last stood. But alas, he failed not in respecting a shadow but in trusting an outline; it was not her in her essence, for she did not move. Now, upon the walls of Aurelia’s chambers, a shadow of a dancer takes her mask off for the first time and the audience whom she has always seen can now see her; the King of France hears of the storming of the Bastille through a whisper, as he sits in his stage balcony, and the tragedy being played out in front of him takes on a morbid sheen; in indoor circus in Russia sees its elephants replaced by heirs and heiresses, whose earrings twinkle as they clap; and, during the performance of her career, a ballerina falls into an open grave as the nuns dance in her wake…

The heartbeat, as they say, is the stamping of the feet, and breathing is the hint of the melodic phrase. As Apollo the sun god banishes the horrors of night and heralds the dawn, the shadows on the wall fade to the ochre. Aurelia does not wake up.

The notes on Aurelia’s condition, of no use to the nuns any longer, are deposited in a dark corner of the monastery and remained there untouched for nearly a hundred years. These are to be found a century later by traveling marauders and sold at the time of the Renaissance to the throne of Italy, which is to be the first site of the ballet--of which the record of Aurelia’s illness is to be the first formal treatise.

***

The birds near the monastery now spread throughout the grounds as starlings, sweeping upwards in a unified gale and then scattering like dark dust upon the fortress turrets. They mirror the scattering of the pigeons at Trafalgar, which seems a far way off, and suggest the scattering of grains that served as Beauchamp’s inspiration for the choreography of his ballet. These birds travel continents easily (if not quickly) and have been known to be the cause of exotic seeds that have been transported and planted as far as North America. These grains came to be traded at high value in the late 18th century on the trading floor at Wall Street, before it was the machine-driven thoroughfare it is now - when it was in fact a trading post for farmers toting bags of grain.

An apple tree now hangs above Aurelia’s grave; the Swainson’s thrush plays with the stalks of grass that move to and fro to the beats of the starlight upon her headstone.