The carnations on the table look exactly like the ones on condensed milk labels. The sight of them cloys. The tiger lilies, though they are a touch shriveled, suggest a low flame waiting to be turned up. The man who called after me stands by his open car at the curb and gestures to the flowers, laid out in bunches side by side. “Take them,” he says. “They’re just going to get thrown out.” I leave the carnations and take the lilies, even if it is inconvenient to carry them on my errand, and a little much, too, walking down the street like a self-proclaimed goddess with a plastic-wrapped torch.

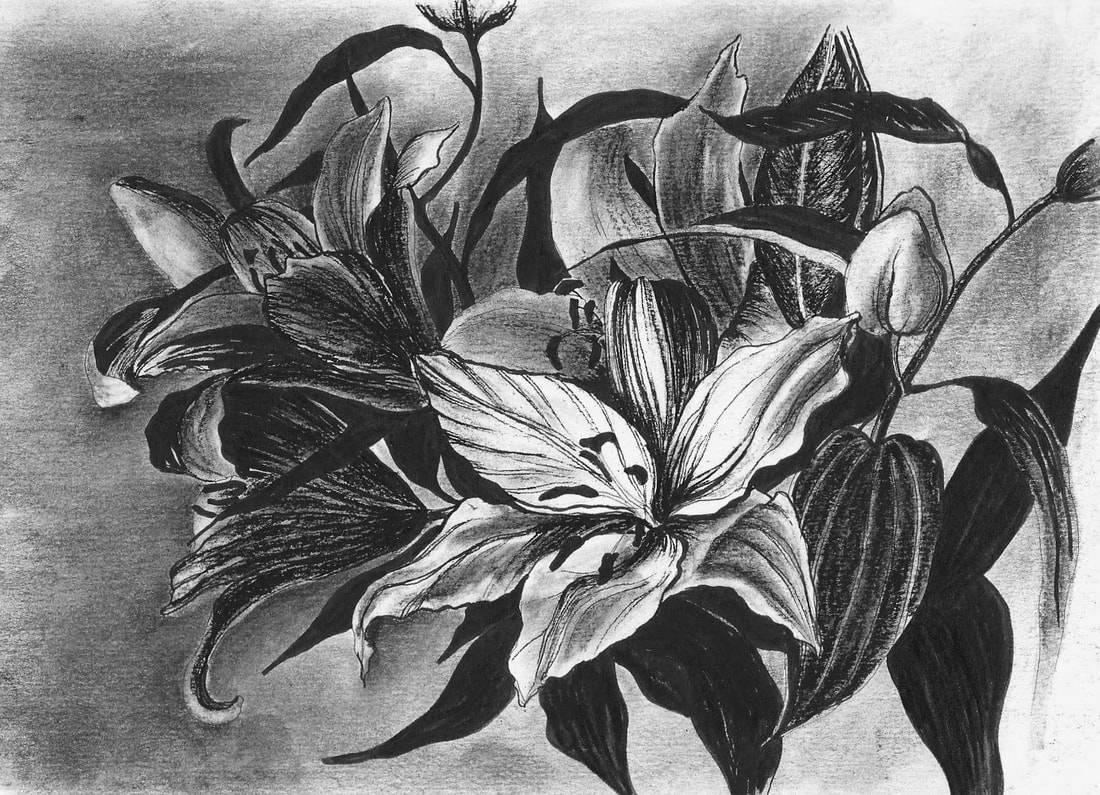

Home now, on my mantle, the lilies bloom, wide and vibrant and sticky. I must take special care to make sure they do not poison the cats. Next to them, a cactus wrapped in foil lurches towards the sun. It is my favorite time of year when New York City dismembers its Christmas trees and arranges them in the spring planters. Look down, see crocuses pushing through the pines, see potted hedges wearing skirts. With the signs of seasons upended, the branches are a reliable emblem of time passing.

So are the flowers. For a year, I bought them almost weekly, budgeting for them, and sometimes not, like food. Now, I find myself more inclined than usual to admire them while out, even the most common varieties. And I find that I admire them more often on screen. I fixate on film flowers because they are impossible to ignore, and they are often a pivotal form of cinematic vocabulary. Take Madeline’s bouquet in Vertigo (1958): procured from a shop she slips into an alleyway to enter, arranged in tight concentricity, structured like the deep void of her blonde bun. A dead woman bringing herself flowers: that’s what it would mean, wouldn’t it, in Hitchcock’s sense. The rough and ready Judy, short on work, acts the part of Madeline, the murdered wife, possessed by the spirit of a woman in a Spanish portrait. If the viewer is ever fooled (and they aren’t), they must believe that Carlotta, the woman inside the wife, visits her own portrait and mimics it with a bouquet identical to the one she held when sitting to be painted.

What a solipsistic ghost Carlotta would be! Maybe I would do the same thing; maybe I’m already doing it, now, my head filled with these flowers that want to be something more than ornamental, more than just dreamy diversions in a symbolically-driven plot. Flowers mark time so well because they distract from it. But they demand time, too, tangled up in all the care and consideration they take to acquire, even offhandedly.

Tiger lilies are the same color as Lucille Ball’s hair. “The hair is brown—but the soul is on fire!” That line, which makes it into Aaron Sorkin’s Being the Ricardos (2021), describes Lucille’s transition into Lucy, the mediocre picture girl’s entry into television stardom. It escapes my mind when, exactly, Lucy dyes her hair, and in any case, one wouldn’t want to see the transformation happen quite so visibly. The flame bursts through and engulfs her, the curls always blazing on the crown of her head, so much her own muse that the marital power struggles on the set of I Love Lucy feel perfunctory.

Those struggles are real, too—they’re in the flowers. The one I Love Lucy episode that figures throughout the entirety of Sorkin’s film, “Fred and Ethel Fight,” begins with Lucy setting the table for dinner. She’s putting a bouquet into a vase, trying to make the flowers stand up without toppling the vase over. After trimming the stems and fumbling with the arrangement, the flowers look to be in place—and then, they push up, making Lucy jump and the live audience chuckle. It’s a petaled memento mori of sorts: for Lucy, for Lucille, for Lucy and Desi’s marriage.

The producers of the episode ultimately have this bit of the sequence removed—you won’t find it in the rerun of “Fred and Ethel Fight.” But Lucille fights for it to be included. The battle of the flowers feeds into a creative disagreement over how Desi should make his initial appearance as Ricky. Lucille thinks it should be kept to a simple, “Honey, I’m home!” The producers think that Ricky should sneak up behind Lucy, covering her eyes and making her guess who it might be. Lucille points out that no matter what task absorbed her, Lucy would never fail to notice an intruder.

Cut the flowers, or cut Ricky’s sneaky entrance?

I wondered how to understand the floral dilemma that anchors the narrative of Being the Ricardos. It lingered in my mind far longer than the questions the film wants to explore in more overt ways—about power dynamics in a marriage, gender and creative control in a 1950s sitcom, political hysteria. The flowers pushing up out of the water, like a gag, like a corpse popping out of a ditch: it somehow encompasses all of these elements, without overdetermining them.

But overdetermination might be the only way to find the place between ornament and duration, the flowers’ apparent lack of function and their persistent reappearance, freshly cut, throughout the film. The argument about whether the sequence of their trimming should be included in the episode looks very much like the one about whether Ricky should sneak up on Lucy. The producers give no good reason for having Ricky sneak into the apartment, and of course, Desi is sneaking around on Lucille over the course of their marriage. This is why it perplexes me to think that the only options the film provides for the sequence consist of credibility and its absence. He either surprises her, or he doesn’t.

The third option, which neither Lucille nor the producers are given to consider, is that the couple knows exactly what they’re up to. Ricky plays a game and Lucy goes along with it—or truer yet to her character, Lucy realizes what Ricky has in mind and disrupts his plans. But the physical outcome of Lucy’s scheming always takes precedent over whatever clever ruse she may concoct. Perhaps this is why it’s so strangely satisfying to see the flowers push back at her in the cut scene.

What if Lucy’s bouquet had suddenly caught on fire—like her soul, manifest through her hair? That would really be within the realm of implausibility; there would have to be candles on the table for Fred and Ethel’s dinner, and that’s simply too much risk for a New York City apartment recreated on a Hollywood film set.

*

On a communal table at a Montana homestead, fire is present and dangerous, and flowers are the language of the tormented soul. A widow named Rose lives there with her son, Peter, who likes making nervous, prickly music by running his thumb across the teeth of a comb. Peter likes making flowers, too; he painstakingly cuts fringes into strips of paper and rolls them up into lifelike blooms. The paper flowers ought to outlast the freshly trimmed, except a sadistic rancher named Phil Burbank, dining with his men at Rose’s table, chooses them as objects of derision. The burning flower is a foregone conclusion: Phil takes one from the vase and incinerates it in a matter of seconds, as Peter watches, expressionless.

By the ending of The Power of the Dog (2021), there is only the rough music of the plastic comb, less nervous now, the replacement for the strings of the banjo Phil plays throughout the film. We don’t need another open carcass to consider that the strings must be made of catgut (a fiber that is only apocryphally associated with cats. It might be any ranch animal). Necks snap and skins stretch, softly, imperceptibly, like flowers. Violence is the film’s silent noise.

Jane Campion’s direction makes these choices come across as deliberate without losing any of their symbolic force. Benedict Cumberbatch, who portrays Phil in the film, has spoken in interviews about the discussions he had with Campion over the course of its production, many of them involving dream imagery. Several of these interviews have mentioned the relative banality of his dream accounts next to Campion’s, which Cumberbatch metonymizes as “exploding orchids of blood.”

The Power of the Dog unites tenderness with brutality, creation with destruction. It can be difficult to absorb all of these things at once—Campion’s careful direction and the unpredictability of even the most carefully controlled action. I love that Peter’s flowers herald a kind of music that moves through even the quietest scenes in the film: that plucking of the comb, the twanging of the banjo strings. They suggest that our experiences of sound and action might diverge. That’s what makes the flowers so laden with meaning. Who do we imagine they are haunting?

After the flower burns, it is Rose who suffers. In one scene, she is desperately trying to read sheet music for the piano. Her husband, Phil’s brother George, fawns upon a skill he’s taken it on trust she can execute, when actually her days as an accompanist to silent films have left her with only a few rudimentary bars. As Rose clunkily attempts to learn the melody, Phil follows on his banjo, first lagging a few seconds behind, starting and stopping with the piano, and then surging forward into an improvised interpretation of the song.

A friend and I disagreed on the strength of Phil’s menace during this scene. She’d been entirely unconvinced by Cumberbatch’s performance. “I thought he was trying to harmonize with her,” she said. But that isn’t quite how Phil inflicts damage: he’s gruff and gradual, inching ever forward into Rose’s personal space, the distance between them an index of just how close he manages to get without touching her. He loosens and tightens the proverbial rope, and she retaliates with recklessness, slipping into an alcoholic stupor that her doting husband overlooks until she is undeniably ill. Anything for the woman who made him feel less alone, even dissembling.

I remain convinced by Cumberbatch’s interpretation of the character, in part because Phil spends the entire film feeling without touching. And god forbid he let anyone know that he feels. The scene by the creek, where he drags a garment belonging to his late mentor, Bronco Henry, from his bare waist to his chin, his body arching beneath its transparent weightlessness, is as powerfully seductive as any thwarted attempt to make contact with Peter, who comes across for Phil as Henry’s younger, more effeminate incarnation. Henry’s presence hangs over the entire film—he’s a character in it, a ghost we don’t see.

“But that’s the direction,” my friend said. “It isn’t the performance.”

What possible answers are there to the question of whether Phil is trying to harmonize with Rose? He is, or he isn’t.

But maybe there is the harmony of accidental collusion. Flowers disrupt clear directorial choices; orchids explode with blood. Why shouldn’t there be a kind of clangorous harmony between Phil and Rose? Isn’t she haunted by her husband’s death? Isn’t the burning flower at her boarding house as much an affront to her union with him as it is to her son’s craftsmanship, which effloresces, over the course of the film, into a scientifically precise deadliness of execution?

Does failing to harmonize with Rose confirm Phil’s monstrosity, or does a temporary alliance with her deepen his humanity—their shared grief for a male partner overriding any imbalance of skill between them?

An orchid masquerading as a rose would smell as sweet.

*

One might still call Phil Burbank a cruel menace, but it is worth thinking about the choice Campion’s film provides—a testament to her exchange with the actors who bring her films to life, as to Lucille Ball’s meticulousness in overseeing the physicality of a scripted scene. Flowers outgrow the scenes they’re given, warping the needle of a film’s moral compass with each cut. They gather the elements around them, returning to earth all that’s ripped from it. Just how this happens—and how stories are assembled from the process—depends more on the unclarity of their ornamental purpose than the decisiveness of any specific symbolic action. Just try to make a flower mean something particular and the story will push back.

The most infamous scene in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) involves a scattering of potentially plot-altering flowers. The scene features in the documentary Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster (2021), a title that suggests the actor’s capability of becoming so completely monstrous that humanity is all that’s left to find in his performances. Stumbling through the growth alongside a lake, Karloff’s creature meets a young girl named Maria, who asks him if he would like one of her flowers. The creature lifts the anemone tenderly between his fingers, and it almost takes on the appearance of a spider there as he sets his lips in bewildered approval. Maria then pops off several of the flowers’ heads, letting them float in the lake. The creature utters a whimper of elation, seeing that he, too, can make the flowers rest on the water’s surface. He turns to the child and seizes her, as she cries out. By the time the creature has tossed her into the lake, it’s too late to think about what, exactly, he meant. The flowers float; the child drowns.

The Man Behind the Monster emphasizes that it was Karloff’s idea to have the creature flee in sudden, agonized realization of the horror he has just committed. For years, however, the scene was censored. Edited versions show the creature’s approach, and cut to Maria’s body being carried through the village.

I find Karloff’s performance equal parts moving and troubling. Some might see a mirror of the child’s innocence in the creature’s actions. I see blank mimicry pendulating with joy. When Maria shrieks, “You’re hurting me,” the last expression we’ve seen from the creature is joy, his back now to the camera. When he turns, his face is frozen in an agonized wail.

There is no question Karloff’s performance colors the monster’s features with unspoken emotion. And yet a century later, an audience hardly has a choice between versions. What would that choice even look like? The creature kills Maria, or he doesn’t intend to. In both versions, she dies.

*

Flowers petal over the ground that shifts with time. They grow back when they’re cut from scenes; their colors burn through ravaged landscapes covered with snow. In one of the final scenes of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car (2021), the twenty-three-year-old Misaki stands in front of the ruins of her family home, slowly tossing the individual flowers of a bouquet that she bought to honor the memory of the mother she chose not to save. She tells Kufuku, her passenger, that her mother had a divided personality, often slipping entirely into the character of a young girl. These moments, Misaki explains, were the only times she was spared her mother’s abuse and manipulation. One might say that Misaki’s mother perished in the collapsed house after a mudslide; Misaki insists that she let her mother die.

She knows exactly what she’s up to: in both versions of the story, the daughter survives.

*

A long, dark winter of flowers, lasting years, lone hands arounds stems submerged in water.

My walks to the cinema have had all the deliberateness of flower-buying, and all the relentless silence of returning empty-handed, thinking how surprising it was to see the tiny buds of cherry blossoms pushing into the cold. One might suppose I’d turn to Virginia Woolf--Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself—but just now, I am not thinking of Clarissa Dalloway’s flowers, the ones on the table when death comes to her party. I am thinking of the cardboard rustling as Lucy opens the box of roses and gladiolas Ricky sends her after giving her a black eye (by accident, of course). That I Love Lucy episode isn’t featured in Being the Ricardos. “Gladiolas!” my mother always said. “Funeral flowers—no wonder you like them.” They’re sometimes known as sword lilies; I like that, too.

If there is poetry in cinematic flowers—if they frustrate, confuse, leave unresolved the details that one could hardly expect to unfold differently in real time—then poetry might go some way towards articulating the terrible splendor of their possibility. As Etel Adnan has it in “The Spring Flowers Own”:

I know flowers to be funeral companions

they make poisons and venoms

and eat abandoned stone walls

I know flowers shine stronger

than the sun

their eclipse means the end of

times

but I love flowers for their treachery

their fragile bodies

grace my imagination’s avenues

without their presence

my mind would be an unmarked

grave.

It seems my weekly errand of flower-buying has shifted to the screen. The flowers are everywhere, and everywhere they evoke the stories of the absent and the dead. I think they must be real. I like going to films alone, because I get to decide for myself, and sometimes I am surprised. The day I took the tiger lilies ended with the evening I saw Drive My Car. Entering the theater, I passed a bouquet of white lilies on the counter of the empty concession stand. Three hours later, I walked through the exit doors. The first sensation I remember is their smell.

Home now, on my mantle, the lilies bloom, wide and vibrant and sticky. I must take special care to make sure they do not poison the cats. Next to them, a cactus wrapped in foil lurches towards the sun. It is my favorite time of year when New York City dismembers its Christmas trees and arranges them in the spring planters. Look down, see crocuses pushing through the pines, see potted hedges wearing skirts. With the signs of seasons upended, the branches are a reliable emblem of time passing.

So are the flowers. For a year, I bought them almost weekly, budgeting for them, and sometimes not, like food. Now, I find myself more inclined than usual to admire them while out, even the most common varieties. And I find that I admire them more often on screen. I fixate on film flowers because they are impossible to ignore, and they are often a pivotal form of cinematic vocabulary. Take Madeline’s bouquet in Vertigo (1958): procured from a shop she slips into an alleyway to enter, arranged in tight concentricity, structured like the deep void of her blonde bun. A dead woman bringing herself flowers: that’s what it would mean, wouldn’t it, in Hitchcock’s sense. The rough and ready Judy, short on work, acts the part of Madeline, the murdered wife, possessed by the spirit of a woman in a Spanish portrait. If the viewer is ever fooled (and they aren’t), they must believe that Carlotta, the woman inside the wife, visits her own portrait and mimics it with a bouquet identical to the one she held when sitting to be painted.

What a solipsistic ghost Carlotta would be! Maybe I would do the same thing; maybe I’m already doing it, now, my head filled with these flowers that want to be something more than ornamental, more than just dreamy diversions in a symbolically-driven plot. Flowers mark time so well because they distract from it. But they demand time, too, tangled up in all the care and consideration they take to acquire, even offhandedly.

Tiger lilies are the same color as Lucille Ball’s hair. “The hair is brown—but the soul is on fire!” That line, which makes it into Aaron Sorkin’s Being the Ricardos (2021), describes Lucille’s transition into Lucy, the mediocre picture girl’s entry into television stardom. It escapes my mind when, exactly, Lucy dyes her hair, and in any case, one wouldn’t want to see the transformation happen quite so visibly. The flame bursts through and engulfs her, the curls always blazing on the crown of her head, so much her own muse that the marital power struggles on the set of I Love Lucy feel perfunctory.

Those struggles are real, too—they’re in the flowers. The one I Love Lucy episode that figures throughout the entirety of Sorkin’s film, “Fred and Ethel Fight,” begins with Lucy setting the table for dinner. She’s putting a bouquet into a vase, trying to make the flowers stand up without toppling the vase over. After trimming the stems and fumbling with the arrangement, the flowers look to be in place—and then, they push up, making Lucy jump and the live audience chuckle. It’s a petaled memento mori of sorts: for Lucy, for Lucille, for Lucy and Desi’s marriage.

The producers of the episode ultimately have this bit of the sequence removed—you won’t find it in the rerun of “Fred and Ethel Fight.” But Lucille fights for it to be included. The battle of the flowers feeds into a creative disagreement over how Desi should make his initial appearance as Ricky. Lucille thinks it should be kept to a simple, “Honey, I’m home!” The producers think that Ricky should sneak up behind Lucy, covering her eyes and making her guess who it might be. Lucille points out that no matter what task absorbed her, Lucy would never fail to notice an intruder.

Cut the flowers, or cut Ricky’s sneaky entrance?

I wondered how to understand the floral dilemma that anchors the narrative of Being the Ricardos. It lingered in my mind far longer than the questions the film wants to explore in more overt ways—about power dynamics in a marriage, gender and creative control in a 1950s sitcom, political hysteria. The flowers pushing up out of the water, like a gag, like a corpse popping out of a ditch: it somehow encompasses all of these elements, without overdetermining them.

But overdetermination might be the only way to find the place between ornament and duration, the flowers’ apparent lack of function and their persistent reappearance, freshly cut, throughout the film. The argument about whether the sequence of their trimming should be included in the episode looks very much like the one about whether Ricky should sneak up on Lucy. The producers give no good reason for having Ricky sneak into the apartment, and of course, Desi is sneaking around on Lucille over the course of their marriage. This is why it perplexes me to think that the only options the film provides for the sequence consist of credibility and its absence. He either surprises her, or he doesn’t.

The third option, which neither Lucille nor the producers are given to consider, is that the couple knows exactly what they’re up to. Ricky plays a game and Lucy goes along with it—or truer yet to her character, Lucy realizes what Ricky has in mind and disrupts his plans. But the physical outcome of Lucy’s scheming always takes precedent over whatever clever ruse she may concoct. Perhaps this is why it’s so strangely satisfying to see the flowers push back at her in the cut scene.

What if Lucy’s bouquet had suddenly caught on fire—like her soul, manifest through her hair? That would really be within the realm of implausibility; there would have to be candles on the table for Fred and Ethel’s dinner, and that’s simply too much risk for a New York City apartment recreated on a Hollywood film set.

*

On a communal table at a Montana homestead, fire is present and dangerous, and flowers are the language of the tormented soul. A widow named Rose lives there with her son, Peter, who likes making nervous, prickly music by running his thumb across the teeth of a comb. Peter likes making flowers, too; he painstakingly cuts fringes into strips of paper and rolls them up into lifelike blooms. The paper flowers ought to outlast the freshly trimmed, except a sadistic rancher named Phil Burbank, dining with his men at Rose’s table, chooses them as objects of derision. The burning flower is a foregone conclusion: Phil takes one from the vase and incinerates it in a matter of seconds, as Peter watches, expressionless.

By the ending of The Power of the Dog (2021), there is only the rough music of the plastic comb, less nervous now, the replacement for the strings of the banjo Phil plays throughout the film. We don’t need another open carcass to consider that the strings must be made of catgut (a fiber that is only apocryphally associated with cats. It might be any ranch animal). Necks snap and skins stretch, softly, imperceptibly, like flowers. Violence is the film’s silent noise.

Jane Campion’s direction makes these choices come across as deliberate without losing any of their symbolic force. Benedict Cumberbatch, who portrays Phil in the film, has spoken in interviews about the discussions he had with Campion over the course of its production, many of them involving dream imagery. Several of these interviews have mentioned the relative banality of his dream accounts next to Campion’s, which Cumberbatch metonymizes as “exploding orchids of blood.”

The Power of the Dog unites tenderness with brutality, creation with destruction. It can be difficult to absorb all of these things at once—Campion’s careful direction and the unpredictability of even the most carefully controlled action. I love that Peter’s flowers herald a kind of music that moves through even the quietest scenes in the film: that plucking of the comb, the twanging of the banjo strings. They suggest that our experiences of sound and action might diverge. That’s what makes the flowers so laden with meaning. Who do we imagine they are haunting?

After the flower burns, it is Rose who suffers. In one scene, she is desperately trying to read sheet music for the piano. Her husband, Phil’s brother George, fawns upon a skill he’s taken it on trust she can execute, when actually her days as an accompanist to silent films have left her with only a few rudimentary bars. As Rose clunkily attempts to learn the melody, Phil follows on his banjo, first lagging a few seconds behind, starting and stopping with the piano, and then surging forward into an improvised interpretation of the song.

A friend and I disagreed on the strength of Phil’s menace during this scene. She’d been entirely unconvinced by Cumberbatch’s performance. “I thought he was trying to harmonize with her,” she said. But that isn’t quite how Phil inflicts damage: he’s gruff and gradual, inching ever forward into Rose’s personal space, the distance between them an index of just how close he manages to get without touching her. He loosens and tightens the proverbial rope, and she retaliates with recklessness, slipping into an alcoholic stupor that her doting husband overlooks until she is undeniably ill. Anything for the woman who made him feel less alone, even dissembling.

I remain convinced by Cumberbatch’s interpretation of the character, in part because Phil spends the entire film feeling without touching. And god forbid he let anyone know that he feels. The scene by the creek, where he drags a garment belonging to his late mentor, Bronco Henry, from his bare waist to his chin, his body arching beneath its transparent weightlessness, is as powerfully seductive as any thwarted attempt to make contact with Peter, who comes across for Phil as Henry’s younger, more effeminate incarnation. Henry’s presence hangs over the entire film—he’s a character in it, a ghost we don’t see.

“But that’s the direction,” my friend said. “It isn’t the performance.”

What possible answers are there to the question of whether Phil is trying to harmonize with Rose? He is, or he isn’t.

But maybe there is the harmony of accidental collusion. Flowers disrupt clear directorial choices; orchids explode with blood. Why shouldn’t there be a kind of clangorous harmony between Phil and Rose? Isn’t she haunted by her husband’s death? Isn’t the burning flower at her boarding house as much an affront to her union with him as it is to her son’s craftsmanship, which effloresces, over the course of the film, into a scientifically precise deadliness of execution?

Does failing to harmonize with Rose confirm Phil’s monstrosity, or does a temporary alliance with her deepen his humanity—their shared grief for a male partner overriding any imbalance of skill between them?

An orchid masquerading as a rose would smell as sweet.

*

One might still call Phil Burbank a cruel menace, but it is worth thinking about the choice Campion’s film provides—a testament to her exchange with the actors who bring her films to life, as to Lucille Ball’s meticulousness in overseeing the physicality of a scripted scene. Flowers outgrow the scenes they’re given, warping the needle of a film’s moral compass with each cut. They gather the elements around them, returning to earth all that’s ripped from it. Just how this happens—and how stories are assembled from the process—depends more on the unclarity of their ornamental purpose than the decisiveness of any specific symbolic action. Just try to make a flower mean something particular and the story will push back.

The most infamous scene in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) involves a scattering of potentially plot-altering flowers. The scene features in the documentary Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster (2021), a title that suggests the actor’s capability of becoming so completely monstrous that humanity is all that’s left to find in his performances. Stumbling through the growth alongside a lake, Karloff’s creature meets a young girl named Maria, who asks him if he would like one of her flowers. The creature lifts the anemone tenderly between his fingers, and it almost takes on the appearance of a spider there as he sets his lips in bewildered approval. Maria then pops off several of the flowers’ heads, letting them float in the lake. The creature utters a whimper of elation, seeing that he, too, can make the flowers rest on the water’s surface. He turns to the child and seizes her, as she cries out. By the time the creature has tossed her into the lake, it’s too late to think about what, exactly, he meant. The flowers float; the child drowns.

The Man Behind the Monster emphasizes that it was Karloff’s idea to have the creature flee in sudden, agonized realization of the horror he has just committed. For years, however, the scene was censored. Edited versions show the creature’s approach, and cut to Maria’s body being carried through the village.

I find Karloff’s performance equal parts moving and troubling. Some might see a mirror of the child’s innocence in the creature’s actions. I see blank mimicry pendulating with joy. When Maria shrieks, “You’re hurting me,” the last expression we’ve seen from the creature is joy, his back now to the camera. When he turns, his face is frozen in an agonized wail.

There is no question Karloff’s performance colors the monster’s features with unspoken emotion. And yet a century later, an audience hardly has a choice between versions. What would that choice even look like? The creature kills Maria, or he doesn’t intend to. In both versions, she dies.

*

Flowers petal over the ground that shifts with time. They grow back when they’re cut from scenes; their colors burn through ravaged landscapes covered with snow. In one of the final scenes of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car (2021), the twenty-three-year-old Misaki stands in front of the ruins of her family home, slowly tossing the individual flowers of a bouquet that she bought to honor the memory of the mother she chose not to save. She tells Kufuku, her passenger, that her mother had a divided personality, often slipping entirely into the character of a young girl. These moments, Misaki explains, were the only times she was spared her mother’s abuse and manipulation. One might say that Misaki’s mother perished in the collapsed house after a mudslide; Misaki insists that she let her mother die.

She knows exactly what she’s up to: in both versions of the story, the daughter survives.

*

A long, dark winter of flowers, lasting years, lone hands arounds stems submerged in water.

My walks to the cinema have had all the deliberateness of flower-buying, and all the relentless silence of returning empty-handed, thinking how surprising it was to see the tiny buds of cherry blossoms pushing into the cold. One might suppose I’d turn to Virginia Woolf--Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself—but just now, I am not thinking of Clarissa Dalloway’s flowers, the ones on the table when death comes to her party. I am thinking of the cardboard rustling as Lucy opens the box of roses and gladiolas Ricky sends her after giving her a black eye (by accident, of course). That I Love Lucy episode isn’t featured in Being the Ricardos. “Gladiolas!” my mother always said. “Funeral flowers—no wonder you like them.” They’re sometimes known as sword lilies; I like that, too.

If there is poetry in cinematic flowers—if they frustrate, confuse, leave unresolved the details that one could hardly expect to unfold differently in real time—then poetry might go some way towards articulating the terrible splendor of their possibility. As Etel Adnan has it in “The Spring Flowers Own”:

I know flowers to be funeral companions

they make poisons and venoms

and eat abandoned stone walls

I know flowers shine stronger

than the sun

their eclipse means the end of

times

but I love flowers for their treachery

their fragile bodies

grace my imagination’s avenues

without their presence

my mind would be an unmarked

grave.

It seems my weekly errand of flower-buying has shifted to the screen. The flowers are everywhere, and everywhere they evoke the stories of the absent and the dead. I think they must be real. I like going to films alone, because I get to decide for myself, and sometimes I am surprised. The day I took the tiger lilies ended with the evening I saw Drive My Car. Entering the theater, I passed a bouquet of white lilies on the counter of the empty concession stand. Three hours later, I walked through the exit doors. The first sensation I remember is their smell.

Amanda Kotch is a writer, educator, and art maker whose work is interested in mortality, ephemerality, the natural world, bodily interiors, sensory experience, relationships and solitude. Her academic background is in nineteenth-century British literature. She teaches at New York University and resides in Jersey City, NJ.