CHAPTER ONE

A turkey vulture drops a rope of intestine and lifts away into a hard blue sky. The dog at the roadside is some kind of mixed breed with a delicate snout and brindled coat. Mel eases the truck to a stop, and I clamp on my hardhat.

Overhead, the big bird carves a dark circle while Mel drags the shovel out of the truck bed. Even though I know the dog is dead, I squat to touch it just in case, but its jaw gapes, its legs are stiff as branches, and its milky eyes are open.

Michelangelo peeled the skins of cadavers. He was searching for a deeper mystery than how muscle attaches to bone. I am searching for something more too; not just a tag to name the owner of a dog. In the dead, Michelangelo found the underpinnings for his art. I haven't yet been able to name what it is I find in these still creatures.

There's no tag on this dog. He's scrawny. I touch a rib bone that pokes through the skin like a tire spoke. Was he abandoned or did he simply leave, the scent of wild things pulling him from the safety of home?

Mel drives a boot on to the shovel's edge and begins to dig. The crunch of hard-packed summer dirt, the scent of forgotten things deep in the earth, the steady rasping pulse of Mel's breathing.

We didn't bury my sister, Goldie, or my father. After the fire they brought two clay urns to the edge of the Kootenay River. The wind picked up the ash and bits of bone, casting them in a wide arc over the cold river. Before they settled into the water, a gust of wind caught a handful of ash and flung it into my mouth.

When we slide the dog into the hole, its skull bone shows white through the cracked bowl of his head. This doesn't cause me to gag the way it used to. I still smell smoke, though, whenever the dull moon of an eye lies exposed like this.

Mel labors onto one knee and opens his fist, letting a confetti of tobacco drift over the small corpse. I keep my eyes on the still form while Mel lifts his head to intone a prayer. I hear “nimoosh” and “miigwech,” the words for “dog” and “thank you.”

The first roadkill I buried was a fox. Nothing about it seemed dead that cool spring morning. It was as if the fox had simply lain down to rest in the middle of the Second Line, the white tip of its tail curled over the sun flare of its body. I'd sensed Mel's eyes on me even though he faced straight ahead. I’d removed my gloves to search for a pulse and found a hardness that made me rock back on my heels.

“Waagosh,” Mel had said.

The fox smelled of juniper and cedar. Turning my head away so Mel couldn't see my face, I'd heard the shovel’s metal-on-metal across the truck sides.

It was the prayer that undid me, the soft syllables like a lullaby.

Once we were back in the truck, Mel touched a finger to the box of tissues tucked into the console and started the engine. When he'd turned to the left to check for traffic, I yanked one from the box and made as if checking traffic from the right.

Mel is the only one I ever want to ride with; the only one who's never made lame lunges to grab my ass on the pretense of helping me into the cab, and the only one who doesn't bitch – not about the weather, the road conditions, or his wife, and not even about the cutbacks that have forced us to drive the snowplows without a wingman.

After we've mounded the earth and tamped it down over the young dog, I toss the shovel into the truck bed and step up into the cab. Mel has the truck in gear.

“Teach me how to pray, Mel,” I say.

Without turning his head, Mel lifts a gray eyebrow.

“You pray to real things, like animals. I need you to teach me.”

His answer comes like it always does, after a long pause. “Don't pray to animals. Pray for them.” Now he turns a half turn, almost facing me. “To give thanks.”

I want some of what he has; that steady sweeping gaze over the land, the ease with which he dangles his fingers through the steering wheel, the slow nod when one of the good old boys at the yard calls him Chief. “Is that what makes you peaceful?”

“Peaceful?” he says as if trying out the word.

“Yeah,” I say. “How does it start? It sounds like bonjour.”

“Boozhoo,” he corrects. “We say, Boozhoo Gzheminido. Means, Hello Creator.”

“The other things you say – after that?”

Mel nods, returns his gaze to the road. “Mshkiki nini ndizhinikaaz, is how I start.”

I try out the words but they feel like pebbles in my mouth. And it looks like Mel is trying not to smile.

“What?”

“You said, ‘My name is Strong Earth Man.’”

“Well, I like that. How do you say, ‘My name is Strong Earth Woman’?”

The smile that was forming vanishes.

There are these times when I feel I've stepped over some sacred invisible boundary. It's in the density of his quiet, as if all the light has been sucked into a vacuum. “What did I say?”

I lean the side of my head into the window and see through the outside mirror that we've done a fine job. Not even a ripple in the gravel remains to mark the spot where the dog is buried. In the beginning, I'd try to insist we find the owners, but if the animals weren't close to a house, the mandate was simply to bury them. No time to go calling door to door.

“Mel, what should I say?”

Easing his foot from the pedal, Mel turns the truck back onto the road. “Just your name.”

“Can't I have a cool name too?”

We're on the road heading south, on the lookout for roadkill, bent signs, and potholes. Sun comes hot and thick through the heavy leaves of maple, oak, and poplar. When Mel doesn't answer, I turn to look full at him. His eyes are closed for a bit too long.

“Mel? How do I get a name like that?”

His eyelids lift and it seems to take some effort for him to focus. He blinks. The fingers dangling from the top of the steering wheel tap at air.

I've screwed things up; the long silence makes that clear. I want to apologize but I'm not exactly sure for what. “Okay, so no special name, okay. So how do I say it with the name I've got?”

The hard line of Mel's jaw softens. “You say your name, then ndizhinikaaz.”

The sharp sound of my own name is jarring when followed by the warmth of the Ojibwe syllables. I want a name that's tough and wild, like Cougar Woman. But given that the man I live with is that much younger than I am, it might not be the best choice. And given that my request has been met with Mel's inscrutable silence, I decide not to push it. After a second attempt at ‘Brett ndizhinikaaz’ I say, “What do you say next?”

From under his eyelids, Mel watches ahead through the sun-stained windshield. “I say, Rama ndoonjibaa, waawaashkeshi doodem.”

This invocation flows like a song, warms me right into my belly, where it's been cold for some time. “Does that mean, ‘I'm from Rama’?”

Mel nods.

“And the rest?”

“My clan.”

“You have a clan? What kind of clan?”

“Deer.”

On the far side of the road, guard posts list toward the ditch, their guide wires stretched tight. “There it is,” I say, pointing.

“I don't have a clan,” I say as Mel swings the truck around in a smooth U. “So what would come next for me?”

“Just where you're from, then ndoonjibaa.”

“Where I'm from?”

“Where your heart is,” Mel says.

“But they're not the same place,” I say.

For the rest of the afternoon Mel and I are mostly silent. That's what I like about him. Once when I asked him why he never asked questions, he told me if a person wanted to tell a thing, they would. When I said that inquiring after the well-being of people you care about was supposed to be the polite thing to do, he just shook his head.

I push on my sunglasses to combat the glare that blazes through the pocked windshield and content myself with watching for potholes to fill and signs to straighten.

“I read somewhere that it's going to be a mild winter,” I say.

Mel glances out his window.

When he doesn't comment, I say, “Late start. That would be good.”

We have the windows open. Neither of us likes air-conditioning, even when it's this hot. A few strands of hair have broken loose from my braid and whip across my mouth. I don't want to think about winter, but when I close my eyes I see snow, ice, sand and brine. A dark empty road and an almost empty hopper. Alone at three in the morning stuffed into my padded coveralls, the drone of engine, the steady scrape of blade, lights – in my rear view, overhead, ahead, blue, red, white – and coming down that hill on glare ice. At the low dip a little blue car revolved like something at a fall fair. I flip open my eyes and resolve anew my pledge to get out before winter sets in.

I'm used to waiting for Mel to answer. When we first started riding together, I'd fill in the quiet by answering for him or asking more questions. Because it finally registered that when I did that he never actually answered, I've trained myself to wait. Now I like the waiting. It's as if the world stops just then and my mind goes still, too.

A slow smile forms on his face. “Once, Web, my older brother, told me we were in for a cold winter. He said you could tell because the caterpillars had thick coats.” Mel scratches the sparse stubble on his chin. His smile fades. “I laughed. I thought he was joking.”

“He wasn't? That's how you can tell?”

Only Mel's eyes move to take a quick look at me. “Maybe,” he says, flicking on the turn signal and spinning the wheel to the right.

“How do the caterpillars look this year?”

His smile is a smaller version of the one a moment before. “It's still hot. Maybe check in September.”

Mel and I replace three road signs perforated with bullet holes, coldpatch half a dozen potholes, remove a fallen ash off a county road and pull a mattress from a ditch. No more dead things today.

At the yard, Mel tips the brim of the ball cap that has replaced his hardhat and we get into our respective vehicles – me in my Yaris, he in “Pony”, his Dodge van that he's snazzed up for camping at pow wows.

* * *

I don't talk about dead animals to Cole. He's a sweet guy with soft hands, except for the calluses on the fingers of the left one. When I get home, I find him on the ottoman by the window. His shape is dark against the yellow afternoon sky, the sun sparking through his hair like new pennies. In the kitchen, I strip off my work clothes and sort them into the washing machine.

Cole likes to sing me songs like “My Girl,” and “Ain't No Sunshine When She's Gone,” but he also writes songs, which the girls who show up at his gigs tell him sound like Ryan Adam's, although, to be honest, I find them a bit corny.

Beckett pads over to the washing machine, his nails clicking on the parquet, and pushes his head against my leg, fur crinkling above his eyes. Beckett is sleek and calm. Cole and I scanned dozens of breeds before choosing a smooth-haired fox terrier. There were many Wire-haired ones available, but we had to go to Missouri to get Beckett. On the drive down, I counted fourteen deer by the side of the highway. For large animals like deer, moose and bear, we use a fork lift. That is, if they haven't been gone too long.

After changing into a clean shirt and jeans I come into the living room. “Listen,” Cole says without turning around. He strums a G and hums for a moment. He doesn't need to do this; he has perfect pitch. Not like me – when I sing, which isn't often, I have to close my eyes and imagine no one. Like after the fire when my cousin Dylan left my room I'd lie on my back and sing made-up songs – not to him, but just for me.

Cole's warm voice streams into the room. I sit with my side nestled into his back. I think about leaving all the time; it’s one thing I do very well. There's always one thing or another to put off the leaving. Cole’s hands for one thing. His mouth for another.

He likes old songs, particularly folk songs from my parents’ time. He’s singing “Fire and Rain” now, which is nice. I close my eyes, letting the vibration from his ribs move mine. But right after the part about things in pieces on the ground, he stops singing and turns to me. “Let’s have a baby,” he says.

“Cole,” I say, trying to breathe some air back into my lungs.

“We could. It’s not too late.” He looks so earnest, so innocent, so trusting. He wants me to think I’m not too old, as if that’s the reason.

“Is the air conditioning on?” I say, unbuttoning my blouse.

Stroking my upper arm, Cole says, “You’d be a great mom.”

I catch his hand and bring it to my mouth, kissing the cup of his palm. “I'm sorry, Cole,” I say, “I can’t.”

He draws away his hand to finger the frayed set list on the side of his guitar, and drops his head so I can't see his face.

“Sex or food first?” I ask into his ear.

“I hate it when you talk like that.”

I straighten my shirt and push myself off the ottoman.

Cole begins to strum, his gaze floating out through the window and over the roofs of our neighborhood.

Beckett follows me to the kitchen, quiet except for the clicking of his nails. I squat and scrub behind his ears. He bows to bat me with the top of his hard skull.

Across the counter are four small plates littered with crumbs, two cereal bowls with gluey flakes, a coffee mug with congealed sugar, a yogurt cup and a glass tumbler stuck with bits of pulp.

“Cole...”

“Norah called.”

I stretch out of my crouch. I don't want to think about Norah; not her flushed hopeful face and not her crumpled one either.

“She wants you to call,” Cole says when I don't answer.

“She has my cell number,” I say.

Beckett's eyes track from mine to his dish. It's still half-full of dry food.

The guitar's strings twang as the hollow sound of its wood reverberates against the wall. I set the dishes into the sink, turn on the tap and squeeze out dish soap in a green line. Beside me Beckett sits, shifting from paw to paw, the skin lifting over each eye into alternate wrinkles. I turn off the tap and reach under the counter to dig into his bag of treats.

Cole is leaning on the archway into the kitchen, one thumb hooked into the front pocket of his jeans.

Beckett takes the chicken-cheese strip in one gulp.

“You should call her,” Cole says, moving close. “What’s with you two anyway?”

“I’ll call her,” I say, although I'm not sure I want to. It’s been sort of strangled between us ever since she had her second miscarriage. I brought her flowers, but I couldn’t stay with her for long. We've both created ghosts, the smell of their breath like those tiny white flowers that show up in sympathy arrangements.

Cole takes my face in both hands. “You okay?”

I kiss him hard, pushing my tongue into his mouth, and drop my hand to his crotch.

We do a quickstep, with me leading and Cole back-stepping, until we fall into the couch. Hoisting one leg over his thighs, I straddle him and unzip his jeans.

“Well, hello there,” I say, running my fingers along the length of his penis.

“Hush, baby,” Cole says, reaching for my face with one hand, my breast with the other. “Come here.” I love the saw-against-wood sound of his voice when he's aroused. Afternoons are my favorite time for sex. Cole hasn't been up for long, so he's full of young male wake-up horniness, and I'm letting down from the stink of the road, my body begging for release.

It's quick and satisfying.

I propel myself off him, leaving a slippery trail across his belly. “I'm starving,” I say.

He doesn't answer. When I turn to ask him what he wants to do about dinner, it doesn't surprise me that his eyes are closed, one arm arched across his forehead, one leg sloping to the floor, his chest with its fine ginger curls circling the nipples in the slow rise and collapse of sleep.

* * *

Cole was twenty-two when I met him, squatting in the aisle of Zehr's with a sliver of skin showing between the knot of his apron sash and the top of his jeans, his hair the color of arbutus bark just before it sheds.

“Aisle Four, about halfway, on the right,” he said, rising to meet my eyes.

His eyes were gold-brown with dark flecks. “Here, let me take you. It's a bit hard to find,” he said, slowing so we could walk side-by-side. “You like Thai food?”

I nodded, taking him all in. “You?”

“I love all kinds of food. Just put it in my mouth and I'll eat it.”

Oh my, I wanted to say, but instead asked him, “What's the strangest thing you've ever eaten?”

His grin revealed perfect teeth. “Frogs. Octopus. Crickets. You?” He indicated a left turn at the end of the aisle.

I gripped his eyes with mine. “Bulls' balls.”

He took in a quick breath and then shot it out with a laugh. “No kidding?” Indicating the shelves of Asian foods, he said, “Here we are.” He hesitated, those fawn eyes scanning me in a way that made me heat and swell. “Bulls' balls, eh? Did it work?”

I hoped that the look I returned made him heat and swell. “I guess it did.”

“Okay then,” he said, wiping his hands down the length of his green apron. Big hands, smooth skin. “I'd better get back to my spices.”

“I'm making cold rolls,” I said, reaching for a pad of rice paper.

“Cool,” he said, taking a small step backward.

“I could make enough for two?”

Five years later he is still almost twelve years younger than I am.

* * *

After finishing the dishes, I rummage through the fridge where I find only a dried-out chicken breast and a bowl of leftover pesto linguine. I begin to tick off dishes from the Indian take-out menu stuck to the fridge when I hear Cole's feet shuffle toward the bathroom, followed by the metallic squabble of curtain rings and the squelch of the bathtub faucet.

“Move over, I'm coming in,” I say, pulling back the shower curtain.

Cole's eyes are shut, face tilted to the spray, his copper lashes against his cheek. The first time I went to one of his gigs, I saw his beauty all over again through the upturned faces of the sleek-haired, tight-jeaned, double-camisole-wearing young women whose cell phones were aimed only at Cole.

He smiles, opens his eyes, and steps to the rear of the tub. I stand under the jet, and he begins to lather my back. Sliding his hands through the space between my torso and arms he cups my breasts. As his hands descend I spread my legs.

“What's that?” he says, sounding alarmed.

“What?”

He points to a viscous brown-red puddle by my feet.

We both watch droplets of water dapple and disperse the blob.

“Mid-cycle spotting,” I say. I take the soap and begin to wash him.

“Brett.” His voice makes me stop.

“Yes?”

“It doesn’t look like that kind of blood.”

Swishing the now pink water with one foot, I escort it down the drain.

He points to the inside of my thigh where a dark, almost brown, trickle of blood has begun. “Maybe you should have it checked, anyway. Just in case.”

When I soap myself and tip my pelvis, the water runs clear. “I'm fine,” I say, parting the curtain and stepping out of the tub.

Of course I'm fine.

CHAPTER TWO

Before pulling the lever, Mel sets his jaw so tight that veins show through the sparse hairs there. I hate the brush cutters too, the way they shred the trees, leaving them left for dead, all twisted and raw. Cost effective and quick, they say.

My cousin Dylan taught me to use a chainsaw when I was twelve. He took me up the mountain after they'd clear-cut to get the surviving cedar. Dylan taught me to buck it, zipping off the branches with deft swipes, and choke it with a heavy chain onto the back of his Jeep so we could drag it down the switchbacks. “You're a real lumberjack now,” Dylan said, planting a warm kiss on my cheek. “A real pretty one.”

The good old boys on the yard stopped their snickering after I cleaned and oiled one and it roared awake with just one pull. Now I’m down in the culvert with a chainsaw getting branches the cutter can’t reach. I'd rather be up close with the trees looking me right in the eyes than be like a drone, ripping them up at a distance. The way some drivers look at me brings a hot flush of shame nonetheless. I'd rather them give me the once-over, wondering who I've blown to get this job than feel the burn of those righteous tree-hugger stares.

When we finish at Road 11, I throw in the chainsaw and climb into the cab. Mel doesn't speak and I don't have much to say either.

I don't know how to pray for the trees.

* * *

I never meant to stay here in this town. I chose it because it was far enough away from the stain left by Mark, my last shitty relationship, but not too far from the city. It was supposed to be a place to make enough money to get further away. East and farther east. As far as I could get. Then farther still.

After taking getting my DZ license, I landed a part time job with the county doing road maintenance. It was good money, I was outside, and I would be gone within a year. But then there was the full-time posting. Then there was Cole. Then, Beckett.

When I get home from work, Cole is still in bed. The warm, slightly sour sleep smell of him wafts through the open bedroom door, thin stripes of late sun through the blinds fan out across the blankets, the rest of the room in darkness. He's been working nights in the bakery for two years. Beckett clicks across the floor and begins to circle his bed, once, twice, three times, before he plops down with a soft sigh. I stand with my shoulder against the door frame and listen for Cole's breathing; his untroubled breathing, and try to imagine his dreams. The covers rustle like shuffling paper as he turns under them.

“Come here,” he murmurs, his long fingers curving in.

As I come to him, he lifts the covers and a cloud of that boy-smell pulls me in.

But after a few moments of lying with my head on his chest, Cole's breathing drops into an even rhythm. I slide off the bed and go to the bathroom. Pulling out the drawer, I stare at the round packet of pills that sit between the tampons and my toothbrush. I hate taking pills, but these are less crazy-making than the ones I took when I was younger. They're called mini pills, as if they're cute. The IUD was so much more convenient. Convenient. But ineffectual. I pop out a pill and swallow it without water.

Cole is still asleep when I come back. I lift the covers and run my tongue along his penis. He jumps, swatting at my head.

“Hey!” I sit up. “That's no way to show your appreciation.”

“Oh, baby, sorry,” he says, propping himself up on his elbows. “I didn't know it was you.”

I laugh. “Did you think it was Beckett?”

A smile begins to shape itself on his face but is replaced by the shock of wakefulness. “What time is it?” he asks, leaping off the bed.

“You've got an hour, yet,” I laugh. “I wouldn't let you be late.”

“Oh.” His shoulders slump as he breathes out, stopping in the middle of the bedroom. “I thought I slept a long time.”

“About five minutes.”

“Oh,” he says again, as if I had said something very wise. He bends to gather up his clothes scattered across the floor and heads to the bathroom.

“I want to travel,” I say to his back.

“Cool,” he says and disappears into the bathroom. The faucet squeaks, followed by the shishing of water that sounds like bubbling bacon fat.

I glance at Beckett curled on his mat, his ears at half-mast and eyes closed but moving under the lids to the sounds in the apartment, and go to the window overlooking downtown. Seedy, small-town downtown, where city planners and restaurateurs constantly attempt to gentrify its crumbling reputation. I have to get out of here. I have to leave. Five years is too long. I open the drawer of my writing desk and slide out my journal.

Don't be such a sissy, don't be such a fool

Open up your wings, let your spirit fly

The roads are smeared with dead things

But you can't stop to cry you can't even cry

Don't even

The rest of that page is blank. On the opposite page I have written an Anais Nin quote: “I am only responsible for my own heart, you offered yours up for the smashing my darling. Only a fool would give out such a vital organ.”

The heart. You can get your heart replaced if it is faulty. I read about a woman who loved opera, ate only organic food and drove an Audi. After she had a heart transplant she craved MacDonald's French fries, hard rock and the long seat of a Harley Davidson. What would someone who received my heart crave? Flight to some tropical isle? The deep thrum of a Mac engine under the scrape and grind of blades? The revelations of entrails? The steady thrust of a young man's hips? Or would they ache for reunion with a fair-haired sister and a quiet, bearded father who were hazing out of focus?

My pen is wedged between the pages. I write: My heart is small and tired. I'm sure I once had a heart that beat strong and knew how to love...

Beside the words, I let the felt tip create loops and tangles. It isn't anything. I draw about as well as I can sing. But my hand continues to move in swirls and zigzags. It stops and the ink continues to leak from the tip, seeping into a blotch, a blossom, a pool of blood.

The Balinese calendar I have pinned to the wall is all blue blues and green greens. In Bali, everything is celebrated, including death. Everyone dances and sings and wears brilliant headgear heavy with fruit. Anais Nin wanted to go there to die, but I don't think she made it. Do the Balinese celebrate roadkill? And how might they celebrate a stillborn or one taken out before its eyes even open?

“That's interesting,” Cole says, making me start. He's right behind me, the moist heat from his belly on my shoulder.

Covering the page with a splayed hand, I ask, “What?”

“Your drawing. It's good.”

When I lift the edge of my hand I see that the ink stain has spread into rivulets that look like entrails and spots of paper show through like eyes.

“What does it look like to you?” I ask.

He touches the page with the tip of a damp finger. “It kind of looks like an animal. Sort of like Beckett.”

What I see is not that, but I don't say so. Sometimes, not often, but sometimes, I can keep my mouth shut.

* * *

When Cole leaves for work, I get ready to take Beckett for his run. The sunscreen smells like that first summer without Daddy and Goldie, in the park at the south end of Kootenay Lake, Mama and Aunt June drinking cups of lemonade by the concession booth while I pushed sand around and listened to other children shrieking and splashing in the water. It was the little ones I couldn't watch. I hated them for being alive.

I fasten on Beckett's leash and we walk down to the lake. Once away from traffic, I let him go and he trots away to sniff and pee and then runs back to keep pace with me as I stride north along the path. The lake is calm and dark, clusters of geese rip its surface as they land, braying at each other like bitter old women. The path is lit in regular pools by streetlight. As soon as the sun disappeared, the wind died and now cooler air pushes in.

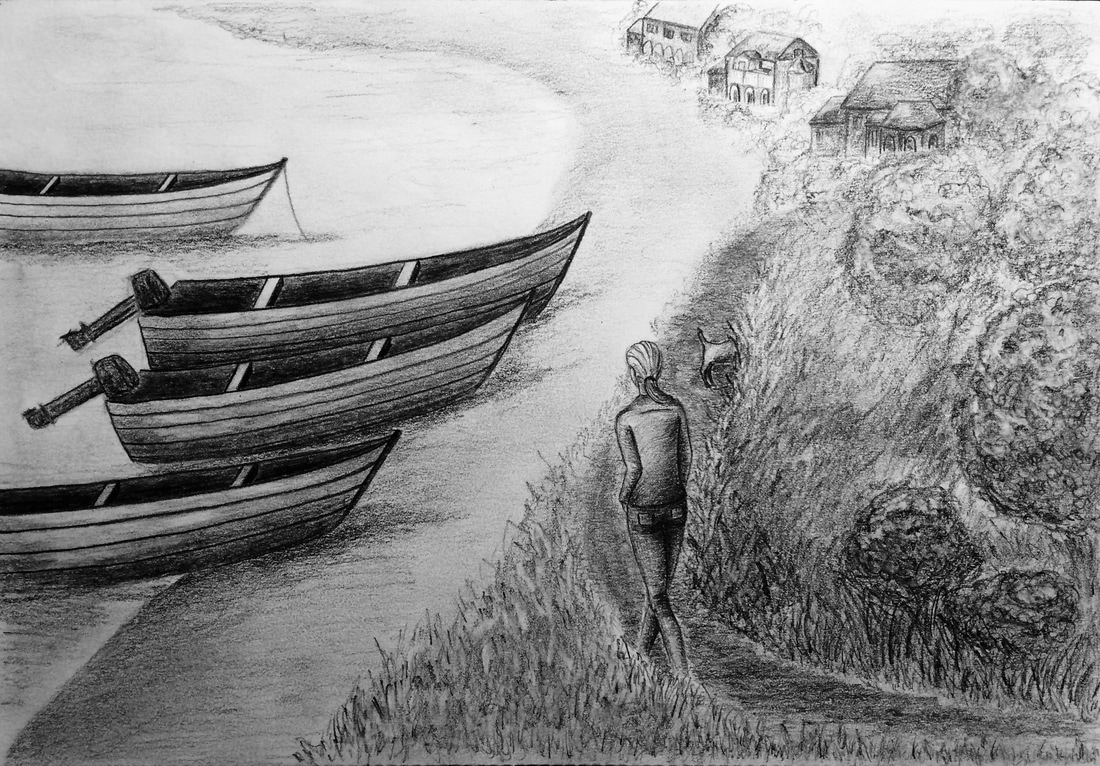

The path veers sharply east and passes under finer homes. Boats lift and tug at their ropes at the edge of the water. I want to untie their moorings, set them free into the open lake. But even the open lake is finite, enclosed. I suppose they might find the mouth to the waterway that would eventually lead to open sea. It's just so easy to get lost along the way, to end up ripped open on jagged rocks or drift for days without making headway.

Beckett squeals and jumps forward, bouncing like a rabbit into a thicket near the water.

“Beckett!” I hurry after him.

One, two bounces and he plunges into the tall grasses and emerges with a black creature clamped in his jaws.

“Drop it!” I shout, but Beckett shakes the animal as if it were a stuffed toy. White streaks in its black fur tell me that it isn't a cat he's caught.

I scream, “Down, Beckett, down! Drop it!”

Beckett's jaws open and the skunk tumbles out. A pissy burnt-coffee smell lifts out of the grasses. My eyes tear and I slap my hand over my mouth. Beckett spins and races back to me. We run along the pathway, Beckett just ahead. We keep running as if we could outrun that smell.

After putting Beckett in the bathroom, I drive to the grocery store. When I walk in through the swoosh of automatic doors into the ice-cool, all heads turn toward me, their faces in an array of shock, disgust and amusement.

I'm putting the last of three large cans of tomato juice in my basket when Cole appears at the end of the aisle. He starts to laugh, but stops by the applesauce about ten feet away.

“Beckett?” he calls down the aisle.

I nod. I had hoped that at least I'd stop smelling it after a while, but it continues to waft around me, just as the singe of Goldie's hair did.

Cole takes a few steps and stops two feet away. “A rose by any other name...” he says.

It's intolerable – my smell. I have to get out of my skin, out of this cold store, out of this town, this country, out of sacrificial animals, even out of Cole. “I've got to go,” I say without looking at him.

Cole takes a long step back. Waving a hand in front of his face, he says, “Good idea.”

I nod, keeping my head down. “I have to get out.”

“So you said.”

“Bali,” I say.

“Bali? That’s extreme,” he says. Then he brightens. “What about a week in Mexico or Cuba? That’d be cheaper.”

I grip the handles of the basket until I feel them cut into my palms. “I don’t want to go for a week. I want to go forever.”

There’s a pause before he laughs.

“I mean it, Cole, I have to go.”

“What?” He takes another step back. “What’s going on?”

I'm starting to feel a bit nauseous. Maybe it's the skunk or maybe it's that stretching twisting sense that I might actually buy a plane ticket and fly across the world. “We’ll talk when you get home, okay?”

He snaps into a rigid stance. “Don't mess with me.” He grips my elbow and steers me close into the shelves, glancing down the aisle at a woman intent on a box's label.

I tilt my head back. “I’m sorry. I just have to go.”

The woman with the box doesn't move.

Cole opens his fingers, but I still feel their imprint. He backs away, his jaw open like the rictus of a cadaver, his eyes narrowed. He starts to walk away but then half-turns. “Tomato juice won’t get rid of that smell.”

A turkey vulture drops a rope of intestine and lifts away into a hard blue sky. The dog at the roadside is some kind of mixed breed with a delicate snout and brindled coat. Mel eases the truck to a stop, and I clamp on my hardhat.

Overhead, the big bird carves a dark circle while Mel drags the shovel out of the truck bed. Even though I know the dog is dead, I squat to touch it just in case, but its jaw gapes, its legs are stiff as branches, and its milky eyes are open.

Michelangelo peeled the skins of cadavers. He was searching for a deeper mystery than how muscle attaches to bone. I am searching for something more too; not just a tag to name the owner of a dog. In the dead, Michelangelo found the underpinnings for his art. I haven't yet been able to name what it is I find in these still creatures.

There's no tag on this dog. He's scrawny. I touch a rib bone that pokes through the skin like a tire spoke. Was he abandoned or did he simply leave, the scent of wild things pulling him from the safety of home?

Mel drives a boot on to the shovel's edge and begins to dig. The crunch of hard-packed summer dirt, the scent of forgotten things deep in the earth, the steady rasping pulse of Mel's breathing.

We didn't bury my sister, Goldie, or my father. After the fire they brought two clay urns to the edge of the Kootenay River. The wind picked up the ash and bits of bone, casting them in a wide arc over the cold river. Before they settled into the water, a gust of wind caught a handful of ash and flung it into my mouth.

When we slide the dog into the hole, its skull bone shows white through the cracked bowl of his head. This doesn't cause me to gag the way it used to. I still smell smoke, though, whenever the dull moon of an eye lies exposed like this.

Mel labors onto one knee and opens his fist, letting a confetti of tobacco drift over the small corpse. I keep my eyes on the still form while Mel lifts his head to intone a prayer. I hear “nimoosh” and “miigwech,” the words for “dog” and “thank you.”

The first roadkill I buried was a fox. Nothing about it seemed dead that cool spring morning. It was as if the fox had simply lain down to rest in the middle of the Second Line, the white tip of its tail curled over the sun flare of its body. I'd sensed Mel's eyes on me even though he faced straight ahead. I’d removed my gloves to search for a pulse and found a hardness that made me rock back on my heels.

“Waagosh,” Mel had said.

The fox smelled of juniper and cedar. Turning my head away so Mel couldn't see my face, I'd heard the shovel’s metal-on-metal across the truck sides.

It was the prayer that undid me, the soft syllables like a lullaby.

Once we were back in the truck, Mel touched a finger to the box of tissues tucked into the console and started the engine. When he'd turned to the left to check for traffic, I yanked one from the box and made as if checking traffic from the right.

Mel is the only one I ever want to ride with; the only one who's never made lame lunges to grab my ass on the pretense of helping me into the cab, and the only one who doesn't bitch – not about the weather, the road conditions, or his wife, and not even about the cutbacks that have forced us to drive the snowplows without a wingman.

After we've mounded the earth and tamped it down over the young dog, I toss the shovel into the truck bed and step up into the cab. Mel has the truck in gear.

“Teach me how to pray, Mel,” I say.

Without turning his head, Mel lifts a gray eyebrow.

“You pray to real things, like animals. I need you to teach me.”

His answer comes like it always does, after a long pause. “Don't pray to animals. Pray for them.” Now he turns a half turn, almost facing me. “To give thanks.”

I want some of what he has; that steady sweeping gaze over the land, the ease with which he dangles his fingers through the steering wheel, the slow nod when one of the good old boys at the yard calls him Chief. “Is that what makes you peaceful?”

“Peaceful?” he says as if trying out the word.

“Yeah,” I say. “How does it start? It sounds like bonjour.”

“Boozhoo,” he corrects. “We say, Boozhoo Gzheminido. Means, Hello Creator.”

“The other things you say – after that?”

Mel nods, returns his gaze to the road. “Mshkiki nini ndizhinikaaz, is how I start.”

I try out the words but they feel like pebbles in my mouth. And it looks like Mel is trying not to smile.

“What?”

“You said, ‘My name is Strong Earth Man.’”

“Well, I like that. How do you say, ‘My name is Strong Earth Woman’?”

The smile that was forming vanishes.

There are these times when I feel I've stepped over some sacred invisible boundary. It's in the density of his quiet, as if all the light has been sucked into a vacuum. “What did I say?”

I lean the side of my head into the window and see through the outside mirror that we've done a fine job. Not even a ripple in the gravel remains to mark the spot where the dog is buried. In the beginning, I'd try to insist we find the owners, but if the animals weren't close to a house, the mandate was simply to bury them. No time to go calling door to door.

“Mel, what should I say?”

Easing his foot from the pedal, Mel turns the truck back onto the road. “Just your name.”

“Can't I have a cool name too?”

We're on the road heading south, on the lookout for roadkill, bent signs, and potholes. Sun comes hot and thick through the heavy leaves of maple, oak, and poplar. When Mel doesn't answer, I turn to look full at him. His eyes are closed for a bit too long.

“Mel? How do I get a name like that?”

His eyelids lift and it seems to take some effort for him to focus. He blinks. The fingers dangling from the top of the steering wheel tap at air.

I've screwed things up; the long silence makes that clear. I want to apologize but I'm not exactly sure for what. “Okay, so no special name, okay. So how do I say it with the name I've got?”

The hard line of Mel's jaw softens. “You say your name, then ndizhinikaaz.”

The sharp sound of my own name is jarring when followed by the warmth of the Ojibwe syllables. I want a name that's tough and wild, like Cougar Woman. But given that the man I live with is that much younger than I am, it might not be the best choice. And given that my request has been met with Mel's inscrutable silence, I decide not to push it. After a second attempt at ‘Brett ndizhinikaaz’ I say, “What do you say next?”

From under his eyelids, Mel watches ahead through the sun-stained windshield. “I say, Rama ndoonjibaa, waawaashkeshi doodem.”

This invocation flows like a song, warms me right into my belly, where it's been cold for some time. “Does that mean, ‘I'm from Rama’?”

Mel nods.

“And the rest?”

“My clan.”

“You have a clan? What kind of clan?”

“Deer.”

On the far side of the road, guard posts list toward the ditch, their guide wires stretched tight. “There it is,” I say, pointing.

“I don't have a clan,” I say as Mel swings the truck around in a smooth U. “So what would come next for me?”

“Just where you're from, then ndoonjibaa.”

“Where I'm from?”

“Where your heart is,” Mel says.

“But they're not the same place,” I say.

For the rest of the afternoon Mel and I are mostly silent. That's what I like about him. Once when I asked him why he never asked questions, he told me if a person wanted to tell a thing, they would. When I said that inquiring after the well-being of people you care about was supposed to be the polite thing to do, he just shook his head.

I push on my sunglasses to combat the glare that blazes through the pocked windshield and content myself with watching for potholes to fill and signs to straighten.

“I read somewhere that it's going to be a mild winter,” I say.

Mel glances out his window.

When he doesn't comment, I say, “Late start. That would be good.”

We have the windows open. Neither of us likes air-conditioning, even when it's this hot. A few strands of hair have broken loose from my braid and whip across my mouth. I don't want to think about winter, but when I close my eyes I see snow, ice, sand and brine. A dark empty road and an almost empty hopper. Alone at three in the morning stuffed into my padded coveralls, the drone of engine, the steady scrape of blade, lights – in my rear view, overhead, ahead, blue, red, white – and coming down that hill on glare ice. At the low dip a little blue car revolved like something at a fall fair. I flip open my eyes and resolve anew my pledge to get out before winter sets in.

I'm used to waiting for Mel to answer. When we first started riding together, I'd fill in the quiet by answering for him or asking more questions. Because it finally registered that when I did that he never actually answered, I've trained myself to wait. Now I like the waiting. It's as if the world stops just then and my mind goes still, too.

A slow smile forms on his face. “Once, Web, my older brother, told me we were in for a cold winter. He said you could tell because the caterpillars had thick coats.” Mel scratches the sparse stubble on his chin. His smile fades. “I laughed. I thought he was joking.”

“He wasn't? That's how you can tell?”

Only Mel's eyes move to take a quick look at me. “Maybe,” he says, flicking on the turn signal and spinning the wheel to the right.

“How do the caterpillars look this year?”

His smile is a smaller version of the one a moment before. “It's still hot. Maybe check in September.”

Mel and I replace three road signs perforated with bullet holes, coldpatch half a dozen potholes, remove a fallen ash off a county road and pull a mattress from a ditch. No more dead things today.

At the yard, Mel tips the brim of the ball cap that has replaced his hardhat and we get into our respective vehicles – me in my Yaris, he in “Pony”, his Dodge van that he's snazzed up for camping at pow wows.

* * *

I don't talk about dead animals to Cole. He's a sweet guy with soft hands, except for the calluses on the fingers of the left one. When I get home, I find him on the ottoman by the window. His shape is dark against the yellow afternoon sky, the sun sparking through his hair like new pennies. In the kitchen, I strip off my work clothes and sort them into the washing machine.

Cole likes to sing me songs like “My Girl,” and “Ain't No Sunshine When She's Gone,” but he also writes songs, which the girls who show up at his gigs tell him sound like Ryan Adam's, although, to be honest, I find them a bit corny.

Beckett pads over to the washing machine, his nails clicking on the parquet, and pushes his head against my leg, fur crinkling above his eyes. Beckett is sleek and calm. Cole and I scanned dozens of breeds before choosing a smooth-haired fox terrier. There were many Wire-haired ones available, but we had to go to Missouri to get Beckett. On the drive down, I counted fourteen deer by the side of the highway. For large animals like deer, moose and bear, we use a fork lift. That is, if they haven't been gone too long.

After changing into a clean shirt and jeans I come into the living room. “Listen,” Cole says without turning around. He strums a G and hums for a moment. He doesn't need to do this; he has perfect pitch. Not like me – when I sing, which isn't often, I have to close my eyes and imagine no one. Like after the fire when my cousin Dylan left my room I'd lie on my back and sing made-up songs – not to him, but just for me.

Cole's warm voice streams into the room. I sit with my side nestled into his back. I think about leaving all the time; it’s one thing I do very well. There's always one thing or another to put off the leaving. Cole’s hands for one thing. His mouth for another.

He likes old songs, particularly folk songs from my parents’ time. He’s singing “Fire and Rain” now, which is nice. I close my eyes, letting the vibration from his ribs move mine. But right after the part about things in pieces on the ground, he stops singing and turns to me. “Let’s have a baby,” he says.

“Cole,” I say, trying to breathe some air back into my lungs.

“We could. It’s not too late.” He looks so earnest, so innocent, so trusting. He wants me to think I’m not too old, as if that’s the reason.

“Is the air conditioning on?” I say, unbuttoning my blouse.

Stroking my upper arm, Cole says, “You’d be a great mom.”

I catch his hand and bring it to my mouth, kissing the cup of his palm. “I'm sorry, Cole,” I say, “I can’t.”

He draws away his hand to finger the frayed set list on the side of his guitar, and drops his head so I can't see his face.

“Sex or food first?” I ask into his ear.

“I hate it when you talk like that.”

I straighten my shirt and push myself off the ottoman.

Cole begins to strum, his gaze floating out through the window and over the roofs of our neighborhood.

Beckett follows me to the kitchen, quiet except for the clicking of his nails. I squat and scrub behind his ears. He bows to bat me with the top of his hard skull.

Across the counter are four small plates littered with crumbs, two cereal bowls with gluey flakes, a coffee mug with congealed sugar, a yogurt cup and a glass tumbler stuck with bits of pulp.

“Cole...”

“Norah called.”

I stretch out of my crouch. I don't want to think about Norah; not her flushed hopeful face and not her crumpled one either.

“She wants you to call,” Cole says when I don't answer.

“She has my cell number,” I say.

Beckett's eyes track from mine to his dish. It's still half-full of dry food.

The guitar's strings twang as the hollow sound of its wood reverberates against the wall. I set the dishes into the sink, turn on the tap and squeeze out dish soap in a green line. Beside me Beckett sits, shifting from paw to paw, the skin lifting over each eye into alternate wrinkles. I turn off the tap and reach under the counter to dig into his bag of treats.

Cole is leaning on the archway into the kitchen, one thumb hooked into the front pocket of his jeans.

Beckett takes the chicken-cheese strip in one gulp.

“You should call her,” Cole says, moving close. “What’s with you two anyway?”

“I’ll call her,” I say, although I'm not sure I want to. It’s been sort of strangled between us ever since she had her second miscarriage. I brought her flowers, but I couldn’t stay with her for long. We've both created ghosts, the smell of their breath like those tiny white flowers that show up in sympathy arrangements.

Cole takes my face in both hands. “You okay?”

I kiss him hard, pushing my tongue into his mouth, and drop my hand to his crotch.

We do a quickstep, with me leading and Cole back-stepping, until we fall into the couch. Hoisting one leg over his thighs, I straddle him and unzip his jeans.

“Well, hello there,” I say, running my fingers along the length of his penis.

“Hush, baby,” Cole says, reaching for my face with one hand, my breast with the other. “Come here.” I love the saw-against-wood sound of his voice when he's aroused. Afternoons are my favorite time for sex. Cole hasn't been up for long, so he's full of young male wake-up horniness, and I'm letting down from the stink of the road, my body begging for release.

It's quick and satisfying.

I propel myself off him, leaving a slippery trail across his belly. “I'm starving,” I say.

He doesn't answer. When I turn to ask him what he wants to do about dinner, it doesn't surprise me that his eyes are closed, one arm arched across his forehead, one leg sloping to the floor, his chest with its fine ginger curls circling the nipples in the slow rise and collapse of sleep.

* * *

Cole was twenty-two when I met him, squatting in the aisle of Zehr's with a sliver of skin showing between the knot of his apron sash and the top of his jeans, his hair the color of arbutus bark just before it sheds.

“Aisle Four, about halfway, on the right,” he said, rising to meet my eyes.

His eyes were gold-brown with dark flecks. “Here, let me take you. It's a bit hard to find,” he said, slowing so we could walk side-by-side. “You like Thai food?”

I nodded, taking him all in. “You?”

“I love all kinds of food. Just put it in my mouth and I'll eat it.”

Oh my, I wanted to say, but instead asked him, “What's the strangest thing you've ever eaten?”

His grin revealed perfect teeth. “Frogs. Octopus. Crickets. You?” He indicated a left turn at the end of the aisle.

I gripped his eyes with mine. “Bulls' balls.”

He took in a quick breath and then shot it out with a laugh. “No kidding?” Indicating the shelves of Asian foods, he said, “Here we are.” He hesitated, those fawn eyes scanning me in a way that made me heat and swell. “Bulls' balls, eh? Did it work?”

I hoped that the look I returned made him heat and swell. “I guess it did.”

“Okay then,” he said, wiping his hands down the length of his green apron. Big hands, smooth skin. “I'd better get back to my spices.”

“I'm making cold rolls,” I said, reaching for a pad of rice paper.

“Cool,” he said, taking a small step backward.

“I could make enough for two?”

Five years later he is still almost twelve years younger than I am.

* * *

After finishing the dishes, I rummage through the fridge where I find only a dried-out chicken breast and a bowl of leftover pesto linguine. I begin to tick off dishes from the Indian take-out menu stuck to the fridge when I hear Cole's feet shuffle toward the bathroom, followed by the metallic squabble of curtain rings and the squelch of the bathtub faucet.

“Move over, I'm coming in,” I say, pulling back the shower curtain.

Cole's eyes are shut, face tilted to the spray, his copper lashes against his cheek. The first time I went to one of his gigs, I saw his beauty all over again through the upturned faces of the sleek-haired, tight-jeaned, double-camisole-wearing young women whose cell phones were aimed only at Cole.

He smiles, opens his eyes, and steps to the rear of the tub. I stand under the jet, and he begins to lather my back. Sliding his hands through the space between my torso and arms he cups my breasts. As his hands descend I spread my legs.

“What's that?” he says, sounding alarmed.

“What?”

He points to a viscous brown-red puddle by my feet.

We both watch droplets of water dapple and disperse the blob.

“Mid-cycle spotting,” I say. I take the soap and begin to wash him.

“Brett.” His voice makes me stop.

“Yes?”

“It doesn’t look like that kind of blood.”

Swishing the now pink water with one foot, I escort it down the drain.

He points to the inside of my thigh where a dark, almost brown, trickle of blood has begun. “Maybe you should have it checked, anyway. Just in case.”

When I soap myself and tip my pelvis, the water runs clear. “I'm fine,” I say, parting the curtain and stepping out of the tub.

Of course I'm fine.

CHAPTER TWO

Before pulling the lever, Mel sets his jaw so tight that veins show through the sparse hairs there. I hate the brush cutters too, the way they shred the trees, leaving them left for dead, all twisted and raw. Cost effective and quick, they say.

My cousin Dylan taught me to use a chainsaw when I was twelve. He took me up the mountain after they'd clear-cut to get the surviving cedar. Dylan taught me to buck it, zipping off the branches with deft swipes, and choke it with a heavy chain onto the back of his Jeep so we could drag it down the switchbacks. “You're a real lumberjack now,” Dylan said, planting a warm kiss on my cheek. “A real pretty one.”

The good old boys on the yard stopped their snickering after I cleaned and oiled one and it roared awake with just one pull. Now I’m down in the culvert with a chainsaw getting branches the cutter can’t reach. I'd rather be up close with the trees looking me right in the eyes than be like a drone, ripping them up at a distance. The way some drivers look at me brings a hot flush of shame nonetheless. I'd rather them give me the once-over, wondering who I've blown to get this job than feel the burn of those righteous tree-hugger stares.

When we finish at Road 11, I throw in the chainsaw and climb into the cab. Mel doesn't speak and I don't have much to say either.

I don't know how to pray for the trees.

* * *

I never meant to stay here in this town. I chose it because it was far enough away from the stain left by Mark, my last shitty relationship, but not too far from the city. It was supposed to be a place to make enough money to get further away. East and farther east. As far as I could get. Then farther still.

After taking getting my DZ license, I landed a part time job with the county doing road maintenance. It was good money, I was outside, and I would be gone within a year. But then there was the full-time posting. Then there was Cole. Then, Beckett.

When I get home from work, Cole is still in bed. The warm, slightly sour sleep smell of him wafts through the open bedroom door, thin stripes of late sun through the blinds fan out across the blankets, the rest of the room in darkness. He's been working nights in the bakery for two years. Beckett clicks across the floor and begins to circle his bed, once, twice, three times, before he plops down with a soft sigh. I stand with my shoulder against the door frame and listen for Cole's breathing; his untroubled breathing, and try to imagine his dreams. The covers rustle like shuffling paper as he turns under them.

“Come here,” he murmurs, his long fingers curving in.

As I come to him, he lifts the covers and a cloud of that boy-smell pulls me in.

But after a few moments of lying with my head on his chest, Cole's breathing drops into an even rhythm. I slide off the bed and go to the bathroom. Pulling out the drawer, I stare at the round packet of pills that sit between the tampons and my toothbrush. I hate taking pills, but these are less crazy-making than the ones I took when I was younger. They're called mini pills, as if they're cute. The IUD was so much more convenient. Convenient. But ineffectual. I pop out a pill and swallow it without water.

Cole is still asleep when I come back. I lift the covers and run my tongue along his penis. He jumps, swatting at my head.

“Hey!” I sit up. “That's no way to show your appreciation.”

“Oh, baby, sorry,” he says, propping himself up on his elbows. “I didn't know it was you.”

I laugh. “Did you think it was Beckett?”

A smile begins to shape itself on his face but is replaced by the shock of wakefulness. “What time is it?” he asks, leaping off the bed.

“You've got an hour, yet,” I laugh. “I wouldn't let you be late.”

“Oh.” His shoulders slump as he breathes out, stopping in the middle of the bedroom. “I thought I slept a long time.”

“About five minutes.”

“Oh,” he says again, as if I had said something very wise. He bends to gather up his clothes scattered across the floor and heads to the bathroom.

“I want to travel,” I say to his back.

“Cool,” he says and disappears into the bathroom. The faucet squeaks, followed by the shishing of water that sounds like bubbling bacon fat.

I glance at Beckett curled on his mat, his ears at half-mast and eyes closed but moving under the lids to the sounds in the apartment, and go to the window overlooking downtown. Seedy, small-town downtown, where city planners and restaurateurs constantly attempt to gentrify its crumbling reputation. I have to get out of here. I have to leave. Five years is too long. I open the drawer of my writing desk and slide out my journal.

Don't be such a sissy, don't be such a fool

Open up your wings, let your spirit fly

The roads are smeared with dead things

But you can't stop to cry you can't even cry

Don't even

The rest of that page is blank. On the opposite page I have written an Anais Nin quote: “I am only responsible for my own heart, you offered yours up for the smashing my darling. Only a fool would give out such a vital organ.”

The heart. You can get your heart replaced if it is faulty. I read about a woman who loved opera, ate only organic food and drove an Audi. After she had a heart transplant she craved MacDonald's French fries, hard rock and the long seat of a Harley Davidson. What would someone who received my heart crave? Flight to some tropical isle? The deep thrum of a Mac engine under the scrape and grind of blades? The revelations of entrails? The steady thrust of a young man's hips? Or would they ache for reunion with a fair-haired sister and a quiet, bearded father who were hazing out of focus?

My pen is wedged between the pages. I write: My heart is small and tired. I'm sure I once had a heart that beat strong and knew how to love...

Beside the words, I let the felt tip create loops and tangles. It isn't anything. I draw about as well as I can sing. But my hand continues to move in swirls and zigzags. It stops and the ink continues to leak from the tip, seeping into a blotch, a blossom, a pool of blood.

The Balinese calendar I have pinned to the wall is all blue blues and green greens. In Bali, everything is celebrated, including death. Everyone dances and sings and wears brilliant headgear heavy with fruit. Anais Nin wanted to go there to die, but I don't think she made it. Do the Balinese celebrate roadkill? And how might they celebrate a stillborn or one taken out before its eyes even open?

“That's interesting,” Cole says, making me start. He's right behind me, the moist heat from his belly on my shoulder.

Covering the page with a splayed hand, I ask, “What?”

“Your drawing. It's good.”

When I lift the edge of my hand I see that the ink stain has spread into rivulets that look like entrails and spots of paper show through like eyes.

“What does it look like to you?” I ask.

He touches the page with the tip of a damp finger. “It kind of looks like an animal. Sort of like Beckett.”

What I see is not that, but I don't say so. Sometimes, not often, but sometimes, I can keep my mouth shut.

* * *

When Cole leaves for work, I get ready to take Beckett for his run. The sunscreen smells like that first summer without Daddy and Goldie, in the park at the south end of Kootenay Lake, Mama and Aunt June drinking cups of lemonade by the concession booth while I pushed sand around and listened to other children shrieking and splashing in the water. It was the little ones I couldn't watch. I hated them for being alive.

I fasten on Beckett's leash and we walk down to the lake. Once away from traffic, I let him go and he trots away to sniff and pee and then runs back to keep pace with me as I stride north along the path. The lake is calm and dark, clusters of geese rip its surface as they land, braying at each other like bitter old women. The path is lit in regular pools by streetlight. As soon as the sun disappeared, the wind died and now cooler air pushes in.

The path veers sharply east and passes under finer homes. Boats lift and tug at their ropes at the edge of the water. I want to untie their moorings, set them free into the open lake. But even the open lake is finite, enclosed. I suppose they might find the mouth to the waterway that would eventually lead to open sea. It's just so easy to get lost along the way, to end up ripped open on jagged rocks or drift for days without making headway.

Beckett squeals and jumps forward, bouncing like a rabbit into a thicket near the water.

“Beckett!” I hurry after him.

One, two bounces and he plunges into the tall grasses and emerges with a black creature clamped in his jaws.

“Drop it!” I shout, but Beckett shakes the animal as if it were a stuffed toy. White streaks in its black fur tell me that it isn't a cat he's caught.

I scream, “Down, Beckett, down! Drop it!”

Beckett's jaws open and the skunk tumbles out. A pissy burnt-coffee smell lifts out of the grasses. My eyes tear and I slap my hand over my mouth. Beckett spins and races back to me. We run along the pathway, Beckett just ahead. We keep running as if we could outrun that smell.

After putting Beckett in the bathroom, I drive to the grocery store. When I walk in through the swoosh of automatic doors into the ice-cool, all heads turn toward me, their faces in an array of shock, disgust and amusement.

I'm putting the last of three large cans of tomato juice in my basket when Cole appears at the end of the aisle. He starts to laugh, but stops by the applesauce about ten feet away.

“Beckett?” he calls down the aisle.

I nod. I had hoped that at least I'd stop smelling it after a while, but it continues to waft around me, just as the singe of Goldie's hair did.

Cole takes a few steps and stops two feet away. “A rose by any other name...” he says.

It's intolerable – my smell. I have to get out of my skin, out of this cold store, out of this town, this country, out of sacrificial animals, even out of Cole. “I've got to go,” I say without looking at him.

Cole takes a long step back. Waving a hand in front of his face, he says, “Good idea.”

I nod, keeping my head down. “I have to get out.”

“So you said.”

“Bali,” I say.

“Bali? That’s extreme,” he says. Then he brightens. “What about a week in Mexico or Cuba? That’d be cheaper.”

I grip the handles of the basket until I feel them cut into my palms. “I don’t want to go for a week. I want to go forever.”

There’s a pause before he laughs.

“I mean it, Cole, I have to go.”

“What?” He takes another step back. “What’s going on?”

I'm starting to feel a bit nauseous. Maybe it's the skunk or maybe it's that stretching twisting sense that I might actually buy a plane ticket and fly across the world. “We’ll talk when you get home, okay?”

He snaps into a rigid stance. “Don't mess with me.” He grips my elbow and steers me close into the shelves, glancing down the aisle at a woman intent on a box's label.

I tilt my head back. “I’m sorry. I just have to go.”

The woman with the box doesn't move.

Cole opens his fingers, but I still feel their imprint. He backs away, his jaw open like the rictus of a cadaver, his eyes narrowed. He starts to walk away but then half-turns. “Tomato juice won’t get rid of that smell.”

Susan E. Wadds. Winner of The Writers' Union of Canada's 2016 short prose contest for developing writers, Susan Wadds' short fiction and poetry have been featured in several literary journals and anthologies. Two of her poems will appear in Room Magazine’s 40.2 issue. Her short story, "Misconception," won the Scugog Council for the Arts literary contest. "What's Left" took first place in Whispered Words short prose contest, judged by Antanas Sileika. Her short story, "Choose the Hammock," was featured in carte blanche Magazine and submitted to The Journey Prize and the Canadian Magazine Awards.

Past President of the Writers' Community of Simcoe County (WCSC), Susan is a graduate of the Humber School for Writers. She is the recipient of an Ontario Arts Council Writers' Reserve, as well as a WCDR (Writers' Community of Durham Region) grant.