“Ahedonism,” she said. She said ahedonism, but she meant to merely describe something rather than permit it. In fact, remanding such terminology to the verbal slagheap beyond non-existence, it joined such other illustrious utterances such as disoperation and manatoit, as having been spoken without first existing. Was it a first-time event, a burst of originalism scarped from the outermost possible reaches? Only time will tell.

Conflation and emollient once subsumed, she could bitter go on yet only humbly continue. She, as a prismatic and all-inclusive crucible of infighting – tug and give, push and pull, recriminating forgiveness – in one person, sheltered a nether-knowing brood of five sisters and one brother from all that could harm and otherwise protect them. Such were they adrift in a void of experience. In many ways she was so much more than was required or necessary, though her name was merely Abel.

The five sisters, who were they? While similar to easy, a thirst for definition of person without experience would reveal an infantile disposition, unhinged of consequences, petty to an extreme, and these five are no different. Ranging in age from precious to ineluctable. Jesu, the oldest behind her, was a battering ram of a young woman filled with the arbitrary combativeness of at least three score and twelve years crammed into her twenty-seven. Her combative streak had earned her two husbands and a not-so-slender file of domestic abuse calls to the crosstown police station; once her unexplained presence at Abel’s breakfast table reached an equilibrium with the need to ask about any new bruises, it was a known fact that her once-youthful nature had expired.

Their young sibling, Knewter, had been the baby for just long enough to espouse a general distrust of insiders that coalesced into the rather dynamic tendency toward openness to anything foreign. The suffering she withstood at the hands of her elder sisters – though whatever she was had not survived it in tact – had prepared her well to assume the role of passive oppressor to the three girls who would come after her. Not to mention the boy.

The karmadharaya Flat Head was only still approaching its zenith.

Abel found herself with the self-imposed other three, Tiene, Piras and Maya, in a woodsy floor of wandering Carolina jasmine when she had the pronouncement, which was quickly ignored by her teenage charges. So she repeated it.

“Ahedonism,” she said. Their heads whirled around.

“We heard you,” Piras announced, somewhat past her sister. Her seldom not-delinquent attention had been taken away by the puncture of their isolation with the stealth approach of a man unknown to them.

“You’re un-happy,” the stranger said toward Abel with a particular emphasis on something beyond the immediate syllabic frankness. She felt herself nod even before doing so and the telemetric pathways of feeling tightened like slack suddenly pulled from drooping power lines.

“And you’re a nickel-mouth tramp. Now go on, get-y out of here and leave us alone,” Abel instructed the stranger, a man in a vamp’s waistcoat with nothing fine about his lower regions to expose or cover, such as was the case.

“I ain’t gonna do it,” he said. Then Abel turned toward her charges carelessly, stood up from the wooded quarter–acre where they had installed themselves and gathered the tattered quilt on which she had been sitting.

“Fine,” she said like a last word, not to be bothered. Ahedonism indeed, but the intruder had skunked her thoughts away and before she could re-affirm this suspicion before her sibling brood, another had taken its place. As she turned after Piras passed, forming their line back toward the path out of the woodsy corner, Abel shot a glare at the stranger which half-spoke of the fear by which she sought to banish him with more than her made-up descriptions of time-lapsed indulgences repackaged for minors. The mélange of quiet rage and distrust lingered in the chlorophylled air behind them as the young woman and the three girls tromped along the overgrown paths to a chorus of flattening weeds and breaking sticks. The sun poked through a lion-bearded cumulous, bathing the woods in a harsh noon-break. Abel pulled back her head scarf, which she had fashioned herself, as sweat formed on her brow and the three in front of her on the path formed a disjointed regiment – two walking too slow and one too fast – behind which she loped like a hapless, horseless Longstreet. A hedonism indeed.

II

“Is he still following us?” Tiene begged in a vacuum of frustration and fatigue. She hated walking and had been pulled into the promenade to the woods under duress of her elder sister. Then returning beneath the stalking constraint of the stranger she would not be mollified with their nearing proximity to the house. “I don’t why we even had to go out like that.”

“Shut up!” Abel directed harshly. “You miss school, you miss a day – you do what I say then.

“Four goes out… five comes back: is that the way it’s supposed to work?” Piras asked sarcastically. No air that couldn’t be sucked out was allowed between them, in whatever array any of these Champions were found, and Abel with the three youngest was no exception.

“Let’s just get to the house; you three go on in. I’ll get rid of him,” she assured them, but her usual forcefulness was misplaced and the three girls looked at each other to see if they’d heard right as they parted with the older sister at the split-rail fence that garlanded the entrance to their place.

The stranger continued to approach with haphazard surveillance of his quarry, stepping along the side of the road without concern of being seen but as though careful to avoid dew on his boot toes and pant legs though the midday sun had long-returned this moisture to more useful confines. Abel watched him look up at her every ten seconds or so as he closed, latched to his limping pace, giving hint in neither direction that their journey had become attended.

“That’s close enough,” Abel yelled and the stranger curiously, suddenly looked up and stopped twenty feet from where the split-rail began. “What do you want?”

“Name’s Mott,” the stranger informed her.

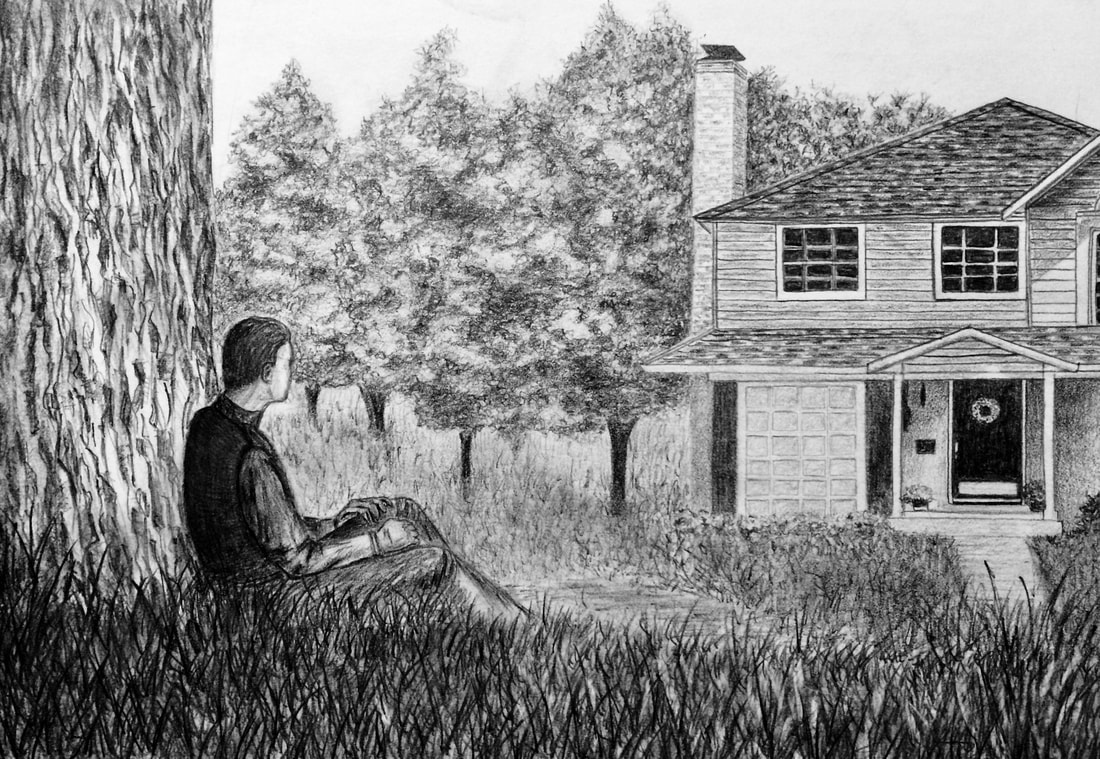

“I don’t care what you’re called; you better get on the hell away from here. I’ll cus you like you wish I hadn’t,” she threatened as one might a fate worse than death. The stranger looked up with a sense newer than old, fresher than stale yet on a putrid verge that dictated all that he might do next he had both thought and perhaps done before. Looking forward upon these past prospects, he turned toward an ancient cottonwood to his left, as uncommon to those parts over the last 75 years as he was right then, and stepped toward it incautiously. Abel watched as he approached the tree, circled it once to find the most hospitable meet-up of roots with ground and seated himself without looking at her again. She remained for a minute longer, waiting to speak several things not in anger but regaining the confusion she had lost in the initial fright he had caused in the woods. But she remarkably said nothing, turned and resumed to join the other sisters and one brother in the house.

At the bottom step leading up to the porch, her pace quickened as she saw the faces pressed into the nearest window and one sister straddling the threshold. “Piras Champion! Get inside the house,” she commanded.

“I was just telling ‘em what you said,” Piras explained.

“What I said to you is the only effing thing you can repeat; haven’t you been listening to anything?” Abel asked with some embarrassment at having so blatantly repeated herself. But recovery awaited her in rage and in the momentum gathered up the steps she whisked the young Piras up by the arm, pulling her through the door as she passed. Then, without hesitation, Abel also whirled around as she let go of the thin arm of her sister and stole a peak out the window in the direction of the old cottonwood. “Where’s your brother?” she asked, though they all knew where he was at that particular moment. Jesu entered the kitchen where her sisters stood and joined them in waiting on Abel to explain her reason for asking such a question to which they all knew the answer. Her impatience flapped vulturous wings. “Well go get him!” Abel thundered.

“But he’s in his trance,” Piras plaintively reminded any who had forgotten. Abel’s eyes shot to the youngest, Maya, who immediately darted off toward the stairs. Her testy eleven-year-old perceptiveness to her sister’s wants and her particular ability to deliver specific sets of them had congealed over half her life to where she could summon these over pride for them only sparingly, and hence quietly bestow her own reward. Her footfalls to the stairs and up them left a moment for the anxious wondering to heighten before Jesu approached Abel and took the hastily folded quilt which was wrapped over her left arm like a poorly contrived bandage.

“What happened?” Jesu asked softly, and though dismissive, Abel could not dispel the upset tender remaining to be returned from her sister’s concern. She shook her head.

“I don’t know… nothing. There’s a man out by the tree, he…” she explained but Piras interrupted.

“He followed us all the way back from our lesson spot. I’m never going back there again,” she said.

“Oh yes!...” Abel began, but turned back to Jesu: “You know, an intrusion like if you’ve left your shoes back away from the water so they won’t get wet only then you suddenly have to run on some sharp rocks? He sort of snuck up on us,” she explained. Jesu peeked beyond her, as if out the window, though she had no angle to see the tree at all.

“Well what’s he supposed to do out there? I mean, is he just sitting there? Waiting on us?” she asked, to no one in particular, and when no one answered, Jesu gathered up the unwieldy quilt, pulled the mass up toward her face to sniff it and disappeared with it into another room.

“You’d better wash that,” Abel suggested, then turned to Piras and repeated: “Where’s your brother?”

“He’s…” Piras laconically replied, with her forefinger and eyebrows pointing to the ceiling above them.

“Oh, I know. I might as well just deal with this myself,” Abel replied in that voice everyone who lived in the house knew so well, that said she was primarily talking to herself. But just as her fear had been vanquished, it was also looking for a place to return as she imagined the man out by the tree, the name he gave, ‘Mott’ and the way he had delivered them back to the house, in flight from his presence. The feeling, an absence of capture, then surrounded her and the emotional head of the family could not regain her place and wished instead to monitor this Mott through the window.

“I said alright – you know I can’t talk now. I’m supposed to be…” Max was saying but fell silent when he saw Abel, not understanding her need but harkening back to his own silence from minutes before. A continuum snapped taut from Max to Abel, seizing his attention. Enveloping his concern for her was the need to revert back to dependable form before those watching them. He tried to see through the haze of terror that blanched her face, before he had to discard it completely. He searched her eyes, and felt the others upon him. “You know I was meditatin’…” he said in complaint.

“There’s a man out by that big cottonwood,” she informed him.

“So… what’s he doing?” Max said.

“Aren’t you going to ask how he got there?” she responded in affront.

“I’d assume he walked. I hadn’t heard any car drive up.”

“You’d be right,” she nodded while adding sarcastically, “that meditation must be working.” Max stepped to the window nearest the porch steps and peered out toward the cottonwood tree. An intruder beyond the property was difficult to assess, still he could not dismiss the degree to which his sister was unsettled. Then he smiled before the gathering.

“Well,” he mused, “if unknown persons you have met and not invited to supper, something must not be right.” Clearing himself before the gathering, no matter its makeup of the women in his house, was of primary concern. For as a living, breathing constituency, they were capable of dethroning him at any moment. No matter that he could not be replaced; it was exactly this which held his fate en extremis and shadowed his every move and subconscious reflection. It was axiomatic that as the strongest in the household, Max remained in a continually proving event of himself to the clan of women he was charged to protect, simply by living with and by virtue of relation, but almost incapable of securing, placed him always at the heart of particular inspection. Because they could not kick him out, he could neither leave nor suggest any sort of rupture where the specific condition of his service to them would be sundered. Instead of bitterness, Max chose meditation, and when it was interrupted he came down with the feint of hope that finding out why might reveal his own release.

As Abel lost patience and turned to leave the front room of the house, Max let the cue settled over him before turning to the door. It was one affect of his meditation, that it made him seem more tranquil, whatever fish swam below. He stepped out onto the porch and listened to the quiet while looking toward the cottonwood. Blankness and virtue walked their dual, lumbering stride out from him before he even made a step toward the yard, and the lightness of foot he felt before walking was the ephemera leftover from his quiet time upstairs before he had been interrupted.

“S’quiet out here,” Max said to the stranger, “You wouldn’t know it from anywhere else.”

“Where’d that woman get to?” the stranger directly asked of Max, who smiled at the suggestion that it was an easy and clear reference. As the stranger increasingly perked up Max slid back into his normal ease, from which he had ventured on his way out to the tree.

“What woman? There’s all kind of – what woman?” Max asked, backing up on his hind thoughts like he was trying to figure something out that had already been figured out. The stranger swung his gaze out to the woods and back, trying to conceal vague boredom with a grin.

“It don’t matter,” he said finally, giving in to the roaring in his stomach that had begun to drown out all else. In appraisal of the stranger, Max began to notice his clothes, a suit, tattered slightly and soiled, unfit for the surroundings except for the worn down aspects the trouser knees and shoulders of the coat had begun to take on.

“What’re you doing out here?” Max asked but the stranger only answered with a question of his own.

“Is that where you live?” he asked, as his eyes shifted to the house beyond the split rail fence. Max spoke proudly.

“Family’s lived here for nearly a hundred years. Grandpa was… founder in Tennessee,” he said remarkably to his own ears.

“What was she doing there?” The stranger asked.

“Who?” Max shot back, puzzled, but the stranger shook his head as he settled back down again.

“Doesn’t matter,” he said.

“I’m afraid much doesn’t seem to matter with you, friend,” Max offered, then added, as an expression of his own autonomy, “should I just leave you here to decide?”

“Or what?” the stranger suggested mildly. The onus cast back onto Max, his decision-making suffered an immediate falter.

“Uh… I don’t know… but you can’t stay here,” Max said, regaining himself somewhat.

“You damn right I can’t; s’gettin’ dark and I got nothing to eat,” the stranger summed resolutely. Increased in the periodic withdrawal from his fellow men, Max felt a brazen authority to lift the man to his bosom, figuratively, and offer him the kind of nourishment and shelter called out for on the fog-shrouded, meditational minefield where he spent much time and considered the state of himself as a part of a female-dominated existence. In this he sensed an ally, and worth, as a consideration or its value, existed wholly outside of the realm of a necessity.

Abel watched as Max helped the stranger to his feet and two men trudged slowly toward the house in the waning dusk light, their heads bowed to obscure what conversation passed between them in their final minute before mounting the steps and entering a parlor that was already making ready for them.

“What the fuck is he doing now?” Abel said into the sheers crowding her face at the window.

“They look like friends. Are they old buddies?” Jesu asked. “Maybe they just knew each other from before.”

“Before what?” Abel scoffed, as they heard the stranger’s boots clomp and smear the grit from their grimy soles onto the front porch boards. The two male voices echoed with common plaint before entering the house, one offering an encouraging laugh to the other’s smirkless agreement that it was much too late in that day to be without dinner and shelter. Singly and simply, they announced themselves through the door without words, just a modest appraisal of the insides of the dwelling mixed with abrupt presentation of the outsides of the stranger at close range.

“Jes… this is mister Mott,” Max began. “Abel…” he said but Abel calmly turned and left the room, though not after taking in the stranger fully again. He turned to Mott, whose foreignness was evaporating quickly into the leaky corners of the house, but turning into hostility in the open passageways. “You’ll have to excuse Abel, she’s…”

“I don’t get those kind,” Mott affirmed vaguely, leaving the unassembled a contemplative opening.

“They don’t even know when to clap,” Max said.

Conflation and emollient once subsumed, she could bitter go on yet only humbly continue. She, as a prismatic and all-inclusive crucible of infighting – tug and give, push and pull, recriminating forgiveness – in one person, sheltered a nether-knowing brood of five sisters and one brother from all that could harm and otherwise protect them. Such were they adrift in a void of experience. In many ways she was so much more than was required or necessary, though her name was merely Abel.

The five sisters, who were they? While similar to easy, a thirst for definition of person without experience would reveal an infantile disposition, unhinged of consequences, petty to an extreme, and these five are no different. Ranging in age from precious to ineluctable. Jesu, the oldest behind her, was a battering ram of a young woman filled with the arbitrary combativeness of at least three score and twelve years crammed into her twenty-seven. Her combative streak had earned her two husbands and a not-so-slender file of domestic abuse calls to the crosstown police station; once her unexplained presence at Abel’s breakfast table reached an equilibrium with the need to ask about any new bruises, it was a known fact that her once-youthful nature had expired.

Their young sibling, Knewter, had been the baby for just long enough to espouse a general distrust of insiders that coalesced into the rather dynamic tendency toward openness to anything foreign. The suffering she withstood at the hands of her elder sisters – though whatever she was had not survived it in tact – had prepared her well to assume the role of passive oppressor to the three girls who would come after her. Not to mention the boy.

The karmadharaya Flat Head was only still approaching its zenith.

Abel found herself with the self-imposed other three, Tiene, Piras and Maya, in a woodsy floor of wandering Carolina jasmine when she had the pronouncement, which was quickly ignored by her teenage charges. So she repeated it.

“Ahedonism,” she said. Their heads whirled around.

“We heard you,” Piras announced, somewhat past her sister. Her seldom not-delinquent attention had been taken away by the puncture of their isolation with the stealth approach of a man unknown to them.

“You’re un-happy,” the stranger said toward Abel with a particular emphasis on something beyond the immediate syllabic frankness. She felt herself nod even before doing so and the telemetric pathways of feeling tightened like slack suddenly pulled from drooping power lines.

“And you’re a nickel-mouth tramp. Now go on, get-y out of here and leave us alone,” Abel instructed the stranger, a man in a vamp’s waistcoat with nothing fine about his lower regions to expose or cover, such as was the case.

“I ain’t gonna do it,” he said. Then Abel turned toward her charges carelessly, stood up from the wooded quarter–acre where they had installed themselves and gathered the tattered quilt on which she had been sitting.

“Fine,” she said like a last word, not to be bothered. Ahedonism indeed, but the intruder had skunked her thoughts away and before she could re-affirm this suspicion before her sibling brood, another had taken its place. As she turned after Piras passed, forming their line back toward the path out of the woodsy corner, Abel shot a glare at the stranger which half-spoke of the fear by which she sought to banish him with more than her made-up descriptions of time-lapsed indulgences repackaged for minors. The mélange of quiet rage and distrust lingered in the chlorophylled air behind them as the young woman and the three girls tromped along the overgrown paths to a chorus of flattening weeds and breaking sticks. The sun poked through a lion-bearded cumulous, bathing the woods in a harsh noon-break. Abel pulled back her head scarf, which she had fashioned herself, as sweat formed on her brow and the three in front of her on the path formed a disjointed regiment – two walking too slow and one too fast – behind which she loped like a hapless, horseless Longstreet. A hedonism indeed.

II

“Is he still following us?” Tiene begged in a vacuum of frustration and fatigue. She hated walking and had been pulled into the promenade to the woods under duress of her elder sister. Then returning beneath the stalking constraint of the stranger she would not be mollified with their nearing proximity to the house. “I don’t why we even had to go out like that.”

“Shut up!” Abel directed harshly. “You miss school, you miss a day – you do what I say then.

“Four goes out… five comes back: is that the way it’s supposed to work?” Piras asked sarcastically. No air that couldn’t be sucked out was allowed between them, in whatever array any of these Champions were found, and Abel with the three youngest was no exception.

“Let’s just get to the house; you three go on in. I’ll get rid of him,” she assured them, but her usual forcefulness was misplaced and the three girls looked at each other to see if they’d heard right as they parted with the older sister at the split-rail fence that garlanded the entrance to their place.

The stranger continued to approach with haphazard surveillance of his quarry, stepping along the side of the road without concern of being seen but as though careful to avoid dew on his boot toes and pant legs though the midday sun had long-returned this moisture to more useful confines. Abel watched him look up at her every ten seconds or so as he closed, latched to his limping pace, giving hint in neither direction that their journey had become attended.

“That’s close enough,” Abel yelled and the stranger curiously, suddenly looked up and stopped twenty feet from where the split-rail began. “What do you want?”

“Name’s Mott,” the stranger informed her.

“I don’t care what you’re called; you better get on the hell away from here. I’ll cus you like you wish I hadn’t,” she threatened as one might a fate worse than death. The stranger looked up with a sense newer than old, fresher than stale yet on a putrid verge that dictated all that he might do next he had both thought and perhaps done before. Looking forward upon these past prospects, he turned toward an ancient cottonwood to his left, as uncommon to those parts over the last 75 years as he was right then, and stepped toward it incautiously. Abel watched as he approached the tree, circled it once to find the most hospitable meet-up of roots with ground and seated himself without looking at her again. She remained for a minute longer, waiting to speak several things not in anger but regaining the confusion she had lost in the initial fright he had caused in the woods. But she remarkably said nothing, turned and resumed to join the other sisters and one brother in the house.

At the bottom step leading up to the porch, her pace quickened as she saw the faces pressed into the nearest window and one sister straddling the threshold. “Piras Champion! Get inside the house,” she commanded.

“I was just telling ‘em what you said,” Piras explained.

“What I said to you is the only effing thing you can repeat; haven’t you been listening to anything?” Abel asked with some embarrassment at having so blatantly repeated herself. But recovery awaited her in rage and in the momentum gathered up the steps she whisked the young Piras up by the arm, pulling her through the door as she passed. Then, without hesitation, Abel also whirled around as she let go of the thin arm of her sister and stole a peak out the window in the direction of the old cottonwood. “Where’s your brother?” she asked, though they all knew where he was at that particular moment. Jesu entered the kitchen where her sisters stood and joined them in waiting on Abel to explain her reason for asking such a question to which they all knew the answer. Her impatience flapped vulturous wings. “Well go get him!” Abel thundered.

“But he’s in his trance,” Piras plaintively reminded any who had forgotten. Abel’s eyes shot to the youngest, Maya, who immediately darted off toward the stairs. Her testy eleven-year-old perceptiveness to her sister’s wants and her particular ability to deliver specific sets of them had congealed over half her life to where she could summon these over pride for them only sparingly, and hence quietly bestow her own reward. Her footfalls to the stairs and up them left a moment for the anxious wondering to heighten before Jesu approached Abel and took the hastily folded quilt which was wrapped over her left arm like a poorly contrived bandage.

“What happened?” Jesu asked softly, and though dismissive, Abel could not dispel the upset tender remaining to be returned from her sister’s concern. She shook her head.

“I don’t know… nothing. There’s a man out by the tree, he…” she explained but Piras interrupted.

“He followed us all the way back from our lesson spot. I’m never going back there again,” she said.

“Oh yes!...” Abel began, but turned back to Jesu: “You know, an intrusion like if you’ve left your shoes back away from the water so they won’t get wet only then you suddenly have to run on some sharp rocks? He sort of snuck up on us,” she explained. Jesu peeked beyond her, as if out the window, though she had no angle to see the tree at all.

“Well what’s he supposed to do out there? I mean, is he just sitting there? Waiting on us?” she asked, to no one in particular, and when no one answered, Jesu gathered up the unwieldy quilt, pulled the mass up toward her face to sniff it and disappeared with it into another room.

“You’d better wash that,” Abel suggested, then turned to Piras and repeated: “Where’s your brother?”

“He’s…” Piras laconically replied, with her forefinger and eyebrows pointing to the ceiling above them.

“Oh, I know. I might as well just deal with this myself,” Abel replied in that voice everyone who lived in the house knew so well, that said she was primarily talking to herself. But just as her fear had been vanquished, it was also looking for a place to return as she imagined the man out by the tree, the name he gave, ‘Mott’ and the way he had delivered them back to the house, in flight from his presence. The feeling, an absence of capture, then surrounded her and the emotional head of the family could not regain her place and wished instead to monitor this Mott through the window.

“I said alright – you know I can’t talk now. I’m supposed to be…” Max was saying but fell silent when he saw Abel, not understanding her need but harkening back to his own silence from minutes before. A continuum snapped taut from Max to Abel, seizing his attention. Enveloping his concern for her was the need to revert back to dependable form before those watching them. He tried to see through the haze of terror that blanched her face, before he had to discard it completely. He searched her eyes, and felt the others upon him. “You know I was meditatin’…” he said in complaint.

“There’s a man out by that big cottonwood,” she informed him.

“So… what’s he doing?” Max said.

“Aren’t you going to ask how he got there?” she responded in affront.

“I’d assume he walked. I hadn’t heard any car drive up.”

“You’d be right,” she nodded while adding sarcastically, “that meditation must be working.” Max stepped to the window nearest the porch steps and peered out toward the cottonwood tree. An intruder beyond the property was difficult to assess, still he could not dismiss the degree to which his sister was unsettled. Then he smiled before the gathering.

“Well,” he mused, “if unknown persons you have met and not invited to supper, something must not be right.” Clearing himself before the gathering, no matter its makeup of the women in his house, was of primary concern. For as a living, breathing constituency, they were capable of dethroning him at any moment. No matter that he could not be replaced; it was exactly this which held his fate en extremis and shadowed his every move and subconscious reflection. It was axiomatic that as the strongest in the household, Max remained in a continually proving event of himself to the clan of women he was charged to protect, simply by living with and by virtue of relation, but almost incapable of securing, placed him always at the heart of particular inspection. Because they could not kick him out, he could neither leave nor suggest any sort of rupture where the specific condition of his service to them would be sundered. Instead of bitterness, Max chose meditation, and when it was interrupted he came down with the feint of hope that finding out why might reveal his own release.

As Abel lost patience and turned to leave the front room of the house, Max let the cue settled over him before turning to the door. It was one affect of his meditation, that it made him seem more tranquil, whatever fish swam below. He stepped out onto the porch and listened to the quiet while looking toward the cottonwood. Blankness and virtue walked their dual, lumbering stride out from him before he even made a step toward the yard, and the lightness of foot he felt before walking was the ephemera leftover from his quiet time upstairs before he had been interrupted.

“S’quiet out here,” Max said to the stranger, “You wouldn’t know it from anywhere else.”

“Where’d that woman get to?” the stranger directly asked of Max, who smiled at the suggestion that it was an easy and clear reference. As the stranger increasingly perked up Max slid back into his normal ease, from which he had ventured on his way out to the tree.

“What woman? There’s all kind of – what woman?” Max asked, backing up on his hind thoughts like he was trying to figure something out that had already been figured out. The stranger swung his gaze out to the woods and back, trying to conceal vague boredom with a grin.

“It don’t matter,” he said finally, giving in to the roaring in his stomach that had begun to drown out all else. In appraisal of the stranger, Max began to notice his clothes, a suit, tattered slightly and soiled, unfit for the surroundings except for the worn down aspects the trouser knees and shoulders of the coat had begun to take on.

“What’re you doing out here?” Max asked but the stranger only answered with a question of his own.

“Is that where you live?” he asked, as his eyes shifted to the house beyond the split rail fence. Max spoke proudly.

“Family’s lived here for nearly a hundred years. Grandpa was… founder in Tennessee,” he said remarkably to his own ears.

“What was she doing there?” The stranger asked.

“Who?” Max shot back, puzzled, but the stranger shook his head as he settled back down again.

“Doesn’t matter,” he said.

“I’m afraid much doesn’t seem to matter with you, friend,” Max offered, then added, as an expression of his own autonomy, “should I just leave you here to decide?”

“Or what?” the stranger suggested mildly. The onus cast back onto Max, his decision-making suffered an immediate falter.

“Uh… I don’t know… but you can’t stay here,” Max said, regaining himself somewhat.

“You damn right I can’t; s’gettin’ dark and I got nothing to eat,” the stranger summed resolutely. Increased in the periodic withdrawal from his fellow men, Max felt a brazen authority to lift the man to his bosom, figuratively, and offer him the kind of nourishment and shelter called out for on the fog-shrouded, meditational minefield where he spent much time and considered the state of himself as a part of a female-dominated existence. In this he sensed an ally, and worth, as a consideration or its value, existed wholly outside of the realm of a necessity.

Abel watched as Max helped the stranger to his feet and two men trudged slowly toward the house in the waning dusk light, their heads bowed to obscure what conversation passed between them in their final minute before mounting the steps and entering a parlor that was already making ready for them.

“What the fuck is he doing now?” Abel said into the sheers crowding her face at the window.

“They look like friends. Are they old buddies?” Jesu asked. “Maybe they just knew each other from before.”

“Before what?” Abel scoffed, as they heard the stranger’s boots clomp and smear the grit from their grimy soles onto the front porch boards. The two male voices echoed with common plaint before entering the house, one offering an encouraging laugh to the other’s smirkless agreement that it was much too late in that day to be without dinner and shelter. Singly and simply, they announced themselves through the door without words, just a modest appraisal of the insides of the dwelling mixed with abrupt presentation of the outsides of the stranger at close range.

“Jes… this is mister Mott,” Max began. “Abel…” he said but Abel calmly turned and left the room, though not after taking in the stranger fully again. He turned to Mott, whose foreignness was evaporating quickly into the leaky corners of the house, but turning into hostility in the open passageways. “You’ll have to excuse Abel, she’s…”

“I don’t get those kind,” Mott affirmed vaguely, leaving the unassembled a contemplative opening.

“They don’t even know when to clap,” Max said.

Alan Flurry is an Athens, Georgia-based writer, filmmaker, and musician. His one-hour documentary "ARCO in Venice" received a Merit Award from the Georgia Association of Broadcasters. He is founding host and producer of the TV interview show, Unscripted with Alan Flurry. His novel Cansville was named one of the Paste Magazine's Best Books of the year in 2013. He plays drums on the Dave Marr album, WE WERE ALL IN LOVE. By pure coincidence, he has a new novel about race and a play about America in the works.