Some evenings when the sky wears a dark face above the sea, my mother calls me to the window, to the sweeping vista over Avaris. We share in the warm breeze that rises from the Nile and gaze out across the palms. In a quiet voice she tells me of the feast of coming home.

Nowadays, I don’t like to dwell on memories like this. It’s hard to think on life before the stranger from the sea. But when my mother weaves her word-spells in the twilight, I give in with pleasure.

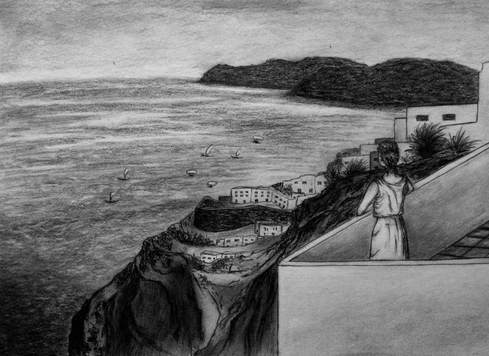

I find myself perched on the topmost house in Thera, nestled like a young skylark with the whole town before me. I see her in her robes again, proud on the high terrace. She makes the holy gesture to welcome in the ships.

Then her words make me a seagull. My breasts skim the waves towards the stately line of ships and I wear the wind like a sheer slip in early morning: cool and loose and free.

Suddenly, and all at once, they’re there—the high sides painted with their many-coloured dolphins, the awnings and the sails billowing and rippling in echo of the water. The tillers all stand to attention and the captains stand in their tents surveying, like little princes, the ranks of deep-bronzed men who heave the oars as one strong heartbeat.

In one or two ships, the oldest hands sit under covered awnings. The others who have served their term are gathered on the shore. They wrap themselves in rich cloaks, their badges of honour, and talk quietly with those old friends with whom they shared the bench. Though there is no disgrace in being past the age of rowing, yet you can see the gleam in every eye in every group: they feel the great call—they long to be part of a whole again.

To start with, though, you can’t quite grasp the mystery. I know for a long time I found the day unnerving. The priestesses—those who judge, who lead, who weave the word-spells of our people—they take their appointed places. For many of us children, these were also our mothers, our teachers, our friends.

But when they appeared to us in those dresses tiered in alternating bands of saffron and lapis lazuli they were also something more. They became the great goddess, the holy spirits painted on the walls in every sacred house. On those days our noise would quiet, and we would let ourselves be led by the chosen guide, as silent as goat-kids when a storm sounds in the distance. Hushed and not quite understanding we would go down through the streets towards the harbour. Oftentimes, the guide was someone I knew well: my aunt, perhaps, or even an older cousin. But never my mother. She had a different role to play.

The year the stranger came, I was nearing thirteen. So, for a long time I had worn this difference like a second skin. No-one had to tell me any more about the things I could not do.

The worst had been the boxing. Here in Egypt they think it strange if girls do any exercise at all, but back in Thera, not only did we take on the boys in the yearly games, but normally we won. And in the midsummer celebrations, when the days reach their longest, we would end the festival with boxing between the nimblest girls, the best of those who had not yet passed through the rites of the great goddess.

Like me, their heads were shaven, save one lock at the front, and a long braid at the back. It was agony to cheer along for two of my best friends. They danced around each other in the last light of the long evening, young lionesses pawing at one another then tumbling away. To know I could have won—could have danced in that adulation—and yet to say nothing, to bear them no unkindness, to cheer with all the rest: that was heavy on me.

If something less was dealt for me, then there was also something more. When the time for our flower harvest came, I knew already that whichever of my friends composed the chosen song, I would be the one to lead the ceremony, the one to sing the spell. It was my job to be a vessel. I had to let the others fill me up, and let the great goddess transmute me as she will. One day, when my mother has gone, I will do the same for all my people, wherever they might be.

The year of the stranger I felt the burden more keenly than ever: this was our year to go up to the fields and collect the saffron, to offer the great goddess the bloom of one flower in exchange for the blooming of another. From then on, we would grow our hair out, cutting off our forelocks to present the goddess with those basketloads of crocus stems.

I knew some girls might start to swell with my responsibility, casting a shadow over all the rest and everything they did. But I had watched my mother well. Soon I found that the more I drew myself back and allowed myself to open, the more the others turned to me to lead.

That day, before the feast of coming home, we were given the holy garments to prepare. This was a little test, and we shared the tense excitement that came with our permission to play a greater role. Little goats no longer (or so we saw ourselves) we rose before the sun and picked our way down to the harbour with the naked fisher boys. At a crossroads, I stopped.

Later, when the great priestesses asked me about this moment, I found it hard to tell them exactly what I felt. After all, it was only the second time I had felt the touch. Now I am older, and am a little closer to the mystery, I can describe it to you a little better, or at least, less badly.

As I said, back on the island we girls would play at all the same games as the boys. Though we did not take to the boats and bring back lines of fish as they would, when the skies looked ill all of us would go together to certain little coves and dive for octopus.

In Egypt, where they look for the raw strength of the hippo or the crocodile, it is hard to convey the magic cunning of our mottled quarry. The way she wraps the shadows around her, or shifts her colour to hide against the rocks. Every one of us had known her blast of ink, and the surprising strength in her soft, thin arms. Half the trick is learning to control your breath. You need to make her curious: diving down before one of the caves in which they make their dens, and hovering above the sand, perhaps blowing out a slow stream of bubbles. You need patience and calm, waiting for the sign—that first curious arm. The boys prefer to use a spear, in practice for their days aboard the ships, but I liked to use my hands. That day I was glad I did.

Looking back, I can see it was the first time I felt the touch. But I had been waiting at the bottom for too long—maybe that is why I didn’t dwell on the strange feeling too much. It was too mingled up with the signs of half-drowning.

We all had shared the sight of the blackness drawing in, as if we had been squirted with ink from either side. That day I knew I was getting close, that I could not risk staying much longer, but I could see the arm drawing further out. It promised an octopus of enormous size. When the feeling began to fade from my finger tips, I had to make a move, so kicking off the seafloor, I made my lunge, aiming for the space between her body and the cave. The octopus, blocked off from her den, shot off into the bay, contracting her great mass through a tiny crevice.

Normally, that would be all; I’d rise up to the surface, draw in the sweet air, and let the others laugh or console me as they like. But I felt a shudder. It ran through me, a bright surge that set me trembling from the tips of my numb toes along my spine up to my scalp, pricking up my forelock like a startled cat.

Although it felt a lifetime, hardly a second had passed and, knowing that I must, I kicked off from the rocks and gave chase over the outcrop out into the bay. By now I really was losing my sight to shadows, but I could still make out her dark form jetting across the sand. She came up short before me, arms wrapped around a dark shape in a spot to which we had never dived before. I fumbled forwards, felt for the thing, and hauling it beneath me, kicked my way up to the surface. I don’t remember reaching air; apparently I breached the surface like a dolphin dancing, then settled on my back clutching the enormous vase.

For a vase it was. It was painted in a style that to my eyes seemed ancient. When we brought it back many of the elders could recognize its type, though none had seen this very piece before. All marvelled at its design. One side showed dolphins swimming around our island. The peak was obvious, with the goddess’s sanctuary and her sacred throne. The other showed a woman who could have been my mother. She had been drawn in thick lines that seemed to throb with power. It was the goddess, one arm to her chest, the other extended out in the gesture of welcome. All took it as a great sign, and for weeks I felt the whispers that rose up in my shadows. I was my mother’s daughter indeed.

The day of the stranger, I felt the touch again. Each of our little troop was laden down with piles of the sacred skirts. But when the boys turned off toward their low fishing boats, I paused. Something about the orange light stretched out across the ocean in rolling lines of mist made me turn towards the east. And then I felt it, rising up my calves and coursing up my spine. I felt my scalp tighten, my long ponytail rise, and my shoulders tightened drawing up my chin. The other girls had fallen silent. When I led us east, away from the bay where we usually washed up, they did not question me, or raise their brows to one another. They trusted.

Still, it did not settle well in me. To try and shrug the worry off, I called for a ball. It’s still the same, even now that we have made our home here: ask any group of Theran girls for a ball to toss, and out will fly a dozen. Before I knew it, we were laughing, trying not to spill our bundles as we tossed and kicked the toy between us, clambering over the rocks towards the reedy bay.

We didn’t go there often. A little spring from on the mountainside made its way down to here, but it used to have an air of secrecy about it. You heard that lovers would meet there for a private tumble; I was not surprised to see two of my friends glance sidelong at each other. You could tell they had the goddess in their eye. She was with me too, that morning, though she played a different role. For between the beds of rushes, naked and bluish-white, lay the broken body of the stranger from the sea.

On other days the other girls would talk about the angles of his legs. You could feel the way his very bones seemed to wound him. Sometimes it was the dead-fish colour of his skin that they remembered, the look you see on drowned men when they wash up days after a storm. It was easy to forgive the others for believing he was dead. And for a few, those with good humour, it was his hair that stayed with him.

Of course we had met Achaeans before; they often came to trade with us, and a few families now had a touch of the golden hair of these north men. But we did not expect to see the pelt that sprouted from this man. His legs were thick with golden bristles, and the thatch around his sex ran up his belly into a deep forest on his chest. Even after we had helped him to recover, he did not shave his body as our men and women do alike, but kept it as thick as the beard we always saw him wear. Only above his lip did he run the razor, and even then, my friends whispered, only to make the beard show thicker.

What I remember, though, more than his storm-wracked body, was the spirit around him. It called to me. Where the others at once believed him dead, drawing back so as not to contaminate the holy robes, I sensed a will to live. I put aside my bundle, and touching my fingers to my temple, felt an echo of the shudder. Not for nothing had we half-drowned ourselves in search of octopus: I knew at once how to expel the brackish water from his chest, to pump sweet air back into this almost-emptied husk.

At last, he spluttered up the final burst of brine, and with my help pulled himself up the beach to lean against a rock. Almost as surprising as his rough, animal pelt was his embarrassment at exposing his sex to us. This was something new, and it puzzles me still: how one can feel ashamed of showing what we all know is there? At least in Egypt, no one minds about our open dresses. Many Egyptian girls wear as little as the bull-dancers on Krete. I wonder how my friends survive who made their way to Ugarit or Hattusi, where they have to wrap themselves in a dozen layers. At any rate, I soon convinced him to borrow one of our shawls, which he wrapped around his waist. He thanked us in a cracked voice, and summoning his formal speech, asked us where he had found himself.

The other girls had shuffled back. This was my role. I spoke for all, but stood apart. He did not recognize the name of Thera but when I described it as the first island north of Krete, his eyes widened and he nodded.

Those green eyes, they seemed to ask me more—perhaps more than I could tell. His ship, his crew: of these I could not yet describe the fates. But as a stranger, he was due all that I could give. So I gave him my name, which he echoed softly back, like the sea when it is caught inside a shell. I told him where to find the great house, how he should approach my mother, the way he must address her. All this he took in as a parched man takes in water: thirsty for kindness.

Before he made his way stumbling up toward our town, he gave me something in return: his own name. Its foreign cadence sounded strange inside my mouth, and I saw the look that darted round the girls when they all heard it. To us, his name sounded exactly like the word for “one who is lost.”

Even close to death, he had a honeyed tongue. He could not tell, he said, whether I was goddess or mortal. At this I felt a knowing look shoot between my friends. It quickened something in me, too, though of a different kind.

Once we had seen him on his way, they asked me why we had not helped him to the town. After all, his limping steps showed how weak he’d grown. I told them that the goddess had sent us there to give help to a stranger, and in return we ought to do her service to repay her. We have these robes, I added, let us not neglect our task.

I did not tell them that I was afraid of what might be said if I passed through the town with my arms around a stranger. So close to our flower harvest, it could prove an ill omen to be seen so close to one of such great spirit—especially if he were overheard making comments like that!

As it was, when we came back into town that evening with the skirts and robes prepared, we felt just like a party returning with captured pirates. I had let the others gossip as the clothes dried in the sun; it could do no harm to wonder at his. My own curiosity was as sharp as theirs.

Something about the way he collected himself told me that this was not the first time that the goddess had delivered him from danger. He even seemed to look at me as if with recognition. It does no good to work over thoughts like this too long: like dough, with too much kneading they grow thick and heavy. So we brought out the ball again, and gradually I turned the conversation to the coming festival. But all our minds burned with a quiet pride as we returned: surely it was a good sign to rescue a stranger before the feast of coming home. After all, that is a day when everyone becomes a stranger.

In the days that followed, I could not help but wonder if that pride had played a part in what took place. The others told me later how they had seen it unfold, and though I could place myself amongst them in my mind, I still catch myself, on black days, wishing I had really been there—as if my presence could have averted the hand of the goddess!

As usual, the night before the feast, each rower had taken his leave and put on a different face. With the evening tide, they had sailed round the island to the harbour-village to the north. As usual, in the morning the youths had all formed into their chorus by the shore, waiting for the arrival of their stranger-family.

No weaving, no painting, no turning pots the day before. Everyone who was not putting on a different face had come together to prepare the welcome feast. Now this was brought out with solemn song to the benches in the square outside my mother’s tower. As usual, she stood proud on the topmost roof in Thera with one hand to her breast waiting to welcome in the strangers, make them family once more.

I did not see it happen. The whole day I waited with the stranger in the shallow room of offering, which in the sacred house sat below the level of the other rooms. It was cool and silent: here I tended to his fever. He had survived the journey to the town, even his audience with my mother, but as night fell the heat rose in him, and though his ribs showed that he had nothing left to give, still he had retched and hurled while the heat raced over him.

I knew how to prepare the poppies, and with their vapours I eased him out of the worst of his struggles. For a long time I tended to him in this half waking slumber, sponging his burning body, tending to his twisted limbs and raw patches of skin with herbs and clear spring water. He seemed to me to be somewhere on the doorstep of the underworld, and several times he broke through the mist of the seeds and called out fearful names—the kind that seemed to come not from our world but that place the Egyptians know so well, where strange creatures emerge from the darkness in monstrous, hybrid knots.

One name was different: when he sounded it, I heard a mixture of desire and loss. It was the name of the she-hawk. Each time his spirit seemed about to depart at last, he would heave his chest and cry this name aloud. It was as if he saw her, circling around his head. And so it was, between the cool silence of the room and his flaring bursts of heat, that I passed the feast day and missed the turning of the tide.

It happened as the first boats began to draw close to the shore. The captains urged their rowers on; the other priestesses called out welcome to the strangers from their allotted balconies. As my friends described it, I could feel the crowd swelling with excitement as if I was there. Bur my mother remained silent as she always did. The goddess was in her. All the signs were good.

Suddenly and without warning the sea began to draw back from the shore—not as the tide does, in slow rolling waves, but like a blanket pulled back from a bed, a rapid jerk revealing long stretches of sand. They told me you could see the crabs—suddenly exposed—racing to find shelter. Several boats were pulled back, far out into the sea, while the leading ones were beached, still too far from the harbour.

At least some of the men managed to keep their cool. Remembering those stories of colossal waves that all the traders know, they quickly leapt down to the shore and, shouting to their teams of rowers, hefted up two of the smaller boats together as best they could, trying to manoeuvre them to higher ground. The other ships they had to leave in the goddess’s hand. On the shore, though, everyone was thrown into a quiet panic.

It was not the first time that we had been shown displeasure: it had rained one year, while two men drowned another. Dark skies, rough weather, or ill-birds they could understand. But this was beyond thinking. Only my mother saved the day from falling into chaos. In that clear, bright voice that I have not yet learned the trick of, she called out over the crowd, stilling them just a word.

She began, This is a day when we remember what is due to the stranger. We put on a foreign face and show that this makes no difference. Everybody here knows our bargain with the goddess: so long as we show proper service to those strangers she throws our way, she will protect our own, and bring them safely back to our shores.

I could picture how these words must have stilled the crowd. When you are used to ceremony sometimes you forget the sacred pact.

She continued, Yesterday, as many of you know, she sent another stranger to our island. His body bears witness to the dangers of the ocean, which all who sail on the great green must understand too well. Did we turn him away? Did we ignore his wounds? No. We welcomed him as if he was a brother or a son returned from some great travels. So, did you think the goddess would not pay heed to our service? She draws back the ocean now to show her power over the sea-father. Look at those plains of sand, hidden for generations. If she can reveal them in just an instant, then surely she can protect us from a sudden wave or tempest? So rejoice! See, even that great wave that the earth shaker might have sent as retribution, she has turned this away.

You can imagine how they feasted after this. Once the remaining boats had been brought close to the harbour, the tables were moved down onto the open shore and my mother led the celebrations from an impromptu throne that the men assembled from some of the boulders that now lay exposed.

In the sacred room, I had little sense of passing time. It caught me by surprise when she came to me at last, and told me the feast was done. She spoke to me as if from a great distance, and when she stroked my forehead it felt as if even her touch was somehow remote. By now the Achaean had settled into a deep sleep; still, my mother asked to take over the tending.

She told me a little of the strange events that day, leaving others to indulge in the dramatic detail, and told me where I could find a little food that had been set aside. As I turned to go she caught my wrist.

Did he say anything, she asked, did he call out through the darkness? She listened deeply, and even with her granite composure, I saw her start when I mentioned the name of the she-hawk. She whispered something to herself. My wrist still in her grasp, she fixed her eyes on me and said, Do not sleep this night. Meet us at the shrine with the first light of dawn. I must convene the others.

You could not be a girl on Thera and not learn, somehow, of the concealed one. Sometimes she was the unnamed threat a mother whispered to her daughter: a monstrous beauty wreathed with snake-hair, whose tribute was those girls who misbehaved.

Other times, from the reverential tones in which the priestesses talked about her, you might think she was the goddess-on-earth. It was when an illness came that was beyond the aid of even the oldest mother, or when there came an omen impossible to understand: those were the times that she was mentioned, and an envoy would disappear at evening, sailing towards the east.

As I waited on the mountain slope, watching the web of stars slowly turn above me, I grew more confident that it was her name my mother had whispered. How the concealed one related to the she-hawk, though, I could only guess. I shivered in the dark.

When the first ring of pink light edged over the horizon I stood up, stretched, and made my way up towards the peak. As I had expected, every priestess was there, breasts bare and hips laden with three- or four-flounce skirts. They lined the pathway to the throne, which had not caught the first light yet.

On a normal day, I would see this one leading the millers, keeping pace and telling stories as they ground the grain from Egypt. That one was the chief weaver, and passed her craft to every boy and girl brought up in the trade. One close to the end I seldom met. She oversaw the storehouse at the far end of town, cataloguing all the material that came in from overseas. Her apprentice scribes would scurry round the dock, taking note of what each ship brought and took away. They would do the rounds of each workshop once or twice a week, documenting what they had produced.

Close to me, with her deep eyes, was my own teacher. Though I would take on my mother’s role one day, I still had to do my part in our daily life. My family had always had the touch for painting, and I worked in the small well-lit room with three other youths on every workshop day learning the craft. She was a light woman, with a graceful, even touch. But she did not give praise lightly, and I am sure now I have learnt this trait from her.

At the end of the rows of women, sitting on the gryphon throne, was the living goddess. You know that, just like me, she has a little upturned nose and wide-sweeping cat’s eyes. But if you could have seen her then, you would not quite believe her beauty. I have never been able to come close.

That morning, all was silent. Then from somewhere nearby a skylark began to sing. The sun was starting to burn orange. The light caught the ivory of the two carved gryphons; their jewel-eyes gleamed. And then her face was lit up by a sudden flare and in one radiant moment the goddess was before me. Around me the two files of priestesses dropped down to one knee and I—who thought she knew her best—could not help but gasp. She looked at me unblinking. She spoke.

Come forwards; you are recognised. The day before the feast, you led the girls to a strange bay in which to do the washing. Explain.

At first, I could not. This was not my mother. The goddess was present. Yet still I wanted nothing more than just to talk to her as we would when I was little. Under the weight of all those heavy gazes I wanted to be close to her, simply to be held. In the end, I took a breath, and tried to tell it as simply as I could.

Around me, the priestesses murmured when I described the shudder. They seemed at once surprised and not surprised. I told them all—but mostly, her—about how I had brought the Achaean back from the doors of death. One of the other women asked me to describe tending to him, so I told them of that, too. Then I caught a glance from the goddess. In a hesitant voice, I told them how he had cried out the name of the she-hawk.

At first I had wondered why I had been called before the conclave. Did they suspect that I had some other foreknowledge of the stranger? But at once it was clear this was the moment the interrogation had been building towards. Everyone fell silent. They knew something I did not. The goddess spoke, Summon the Achaean to speak before us.

Her voice was clear. It carried down the peak. And in the distance I heard footsteps. Slowly, through the gateway, came the stranger from the sea, led by one of the women I had missed earlier. His weakness was obvious, but he kept his chin high, and when he came up next to me, I caught the brilliance of his eye.

Perhaps it was the presence of the goddess but something else caught hold of me. I turned to the stranger, the one who was lost, and said, You stand before the Mistress of All. Do not try to hide behind smooth words today. Tell us truthfully how you came here, and what you know of the she-hawk. There was a murmur of consent. He looked at me, then at the goddess. He swallowed. He spoke.

Here, his story is still sometimes heard down in the docks; it’s said they like to retell it all over the northern lands. Who knows how he remembered it to his town when he returned. All that I can say is, before the gryphon throne, he did not breathe a lie.

We came from Ithaka, he said. There, I am king and chief priest. He looked a little bashful here. He knew he was before a greater power. Our fleet of twelve ships set out to win gold and renown. His voice, which had grown stronger, suddenly stuck in his throat. He had met her gaze. That is, he said, to put it bluntly, we were pirating.

Our ships were well-laden when we came across the island. One of the older hands had heard it was a sanctuary. We could see large flocks of sheep, and smoke rising from the mountainside. So my ship made land while the others waited a little out to sea. We found a cave, a rugged cleft in the mountainside. It was rich with offerings. The walls were daubed with crude pictures, and it was clear to all this was a shrine to the earth-shaker.

We heard footsteps approaching, so were not caught by surprise when we saw the priest. He was taller by a head than any of my men, and sturdier too. In our land, we honour the stranger too, and I made obeisance towards him, asking for the rights of the guest.

He stopped again. No birds cried out, though I could see swallows darting around the sanctuary now the sun had risen. No one stirred amongst the priestesses. Their eyes were all on him. He said, softly, so soft that you might miss it, He refused. He laughed at us, called us mangy dogs, and ordered us to leave on pains of a thrashing. Perhaps I could have stomached a mere refusal. After all, the food was dedicated to the one with the blue hair. But to suffer such insults before my men, my people? It was too heavy to bear.

He looked for a moment like a swimmer caught in rough surf, his head up for air. He knows he cannot stay there treading water long. So he plunges on. We had left our weapons on board as a sign of good faith. Pirates perhaps we were, but no barbarians. I snatched up one of the burning torches, and sweeping before my men, thrust it in his face. His hands clawed at his eyes as he let out a monstrous howl, while my men and I slipped out between the grazing flock outside. Blinded, he still could summon up his friends, and as we gained our ships they came, lumbering shepherd priests down from the grazing slopes.

I lost many men to the heavy stones they hurled down with their slings. They were like the bolts the thunderer lets loose from on high. And all the while, their blind chief called out a curse upon me and all who followed my sail. A grim feeling settled on us as we rowed out from the bay. I remember wiping the blood of a close friend from off my calf. We had to leave his body to the carrion. That dark mood was nothing to what we were to feel.

At first the winds seemed favourable, and we let out the sails and seemed to make good progress. Without warning, though, the wind changed direction, bringing with it storm clouds and colossal waves. Before long, driven deep into the ocean, our fleet began to separate. A flash of a signal from the crest of a wave was the last I saw of any of the other ships. From then it was all that we could do, after our losses on the island, to keep the water out and our ship upright. I could tell you stories of the things I made out dimly through the roiling clouds—here he stopped, looked at the ground, and said, softly again, But in the end, after more than a day, we ran aground. Our ship, like our bodies, had been broken.

On the shore, I drifted in and out of sleep for a long time. As night crept closer I managed to draw myself up. I thought I saw strange creatures, more animal than man, coming towards us from the woods that sloped above us. But darkness swallowed me. When I came to once more I was lying on a bed, inside a high-roofed house. Through the wide window I could see across a clearing to the woods. Birdsong flooded in, and underneath, the steady drone of bees. A noise to my other side surprised me. It was the she-hawk.

All the months I lived there, I never saw her without animals. Even when we lay together, she would have a monkey perched on the footboard, or cats would play around us as we tumbled in the sheets. That first day, I saw her with a hawk perched on her shoulder. Later, she told me that was her title and name.

She led me to my crew, who lay in a deep sleep across a row of mattresses. That she had known without words that I was their king convinced me at once of her sacred powers. It was only as I inspected their bodies, though, that I began to sense how great those powers were. I had managed to make out, through the mist of my half-sleep, how bruised and torn my fellows were, strewn across the beach. But now I saw their wounds were gone. I checked my limbs, then, too and saw that she had cured me of all my pains. I began to ask her how she had managed this, but she pressed a finger to her lips, and drew me outside.

This is my island, she told me, And here, if I desire it, it is so. She looked at me then, and I felt my legs suddenly go stiff. It was a terrible gift. I must own to my own part in staying there so long. She was truly beautiful, and life on her island was as it must be with the gods. But whenever my head began to truly clear, and thoughts of home took over me, she would summon that look and root me to the spot.

The crew she kept in other ways, as I quickly discovered. They woke over the course of the day, and though she told us to stay out of the large house, she gave us the run of the island. After a little exploration, we rested in a pleasant spot at the edge of the clearing, smiling at the play of all the animals. In the early evening she gathered us for a feast. We sat along a great table with places laid out for all. I was seated next to her, and when we all had settled, she called out for food and wine. We all looked to the entrance wondering, for we had seen no indication of another person on the island—just her vast menagerie.

They wore the ragged skins of beasts and, with their dumb expressions and jerking movements, seemed more animal than man. The sight of these, her servants, made us all a little queasy. But the food they brought out smelled delicious, and the wine that one bristling, pig-nosed man poured out for us had a rich lustre. I watched my men as they fell into eating. Just the smell from the heaving table made my stomach tighten. Only then did I remember how long it had been since I had last tasted food.

But I felt a voice, a whisper, tugging at my ear. Perhaps it was my daemon. It stayed my hand, and I did not drink from the wide wine-cup, or eat the cheese and rich, honeyed soup. Instead, I broke a little of the plain bread that the she-hawk had before her, and chewed it carefully, watching over my crew.

The transformation happened quickly. Their black of their eyes grew wide, their movement more erratic, and soon they were no longer eating like men, but grunted like animals, plunging their faces into bowl and wine-cup. I stood up, and if I had my sword, would have drawn it without question. But she summoned her look and bound me to the floor. Then, if you believe me, she laughed, leaned up, and kissed me.

Here the stranger’s voice caught in his throat once more, and I took a moment to glance around the peak. Two of the priestesses had turned to one another, but the rest stood still, gazing at the man. Even the living goddess seemed deep in contemplation. But I also felt a hum of recognition running through them all.

Now I am free of her, he said at last, I would rather not dwell too long on these last months. It makes me feel queasy again just remembering. I may not have given in to the animal delights that her potions offered, but I lived no better than an animal myself. I watched as my crew lost their senses further every day, and gave myself over to yet other kinds of pleasure. Yet through it all, the thought of coming home would return to me, sometimes with my dreams, other times with the distant smell of the sea carried over the woods.

In the end—and here the stranger turned to look at me—It was a vision of the goddess that convinced me to leave. A few of my men I managed to talk out of their deep obsession. With them at my side, the she-hawk could no longer restrain me with the power of her gaze. The moment she realised her powers had failed, she sang a different tune, and bade some of her willing-slaves help us to build a new craft. She gave us charms to ward away ill weather, and told me the secrets of which currents to catch to find my way back home.

The stranger sighed. I was only half listening. I was lost in thought, remembering the way he had looked at me when I had revived him on the shore.

I must not have followed her instructions, he said. I was sure that, when we left, she bore us no ill-intention. But two days out, we hit another storm. That is the last thing I remember before this—he looked at me, and could not seem to find the word he wanted, then, finished, lamely,—this girl brought me back to life.

He looked up at the goddess. If any word I say has been a lie, he said, confident once more, You may strike me down. I know such things to be within your power.

When her judgment came it rolled down like a wave. You speak truly, Achaean, she began. You came to us a stranger, and we have shown you all the care demanded of the host. Yet still more is demanded. This day, a stout ship will be fitted out with all the strongest hands, and they will take you back to Ithaka—return you to your land. You were not cast down again for nothing; your coming has brought great signs for our people. Now it is in our hands to repay you for your suffering.

The stranger was speechless. I wondered afterwards if he had perhaps expected punishment, not reward. The priestesses all nodded. Not one of them appeared to be in any way surprised. Four of them now stepped forwards, and escorted the Achaean back down to the town. The others bowed before the goddess; I caught the action, bowing too, but when I stood up, saw that they were filing out in turn. The sun was high, and a flash of it left me blind for a moment. When I turned back towards the throne, blinking back my sight, I found myself alone.

I still remember that first brush of salt spray against my face. I had been in and out of the ocean my whole life, but the journey to the island was my first time aboard a ship. The light was still dim when we left. The rowers cut a smooth path between the circle islands, which loomed as shadows in the distance, but every now and then the prow would hit a larger wave and send a fine mist across our faces.

We left early. It was important that we slip away before the ceremony where the stranger took his leave. I was still young, so don’t think badly of me if I tell you that I hoped he’d look for me amongst the crowd when he boarded the flagship.

The town had hardly settled from the omen and the feast. When I made it back down from the peak, I had expected everyone to feel the same deep stillness I had experienced alone. But as I joined the others in the house of images, I found them light and chattering. However hard I tried, I could not raise my spirit up and meet them in lightness. An expectation weighed on me. Something more was coming.

When at last the painter master took my shoulder and led me aside—when she whispered to me that I was summoned to the tower—I was not surprised. If anything, I felt relief. Equally, when I knelt before my mother and the gathered women, I understood what they were about to ask me before their words were out.

There was a nervous energy running bright between them. One started to say something, when my mother interrupted. She needs to know, she said. Then, looking closely at me, she sighed. This she-hawk is no ordinary woman, she explained. She is—she is close to the goddess. The stranger did not come to us by chance. She wanted us to meet him, and we think her reason is connected to the unexpected tide.

The women shifted around her, and she looked still more uncomfortable. Now in the private quarters, they were all simply dressed—just a single blue skirt wrapped over their clean white linen dresses. This was my mother speaking, I realised. Human. Fallible.

You were the one who found him, she said to me at last. The message came to you. You felt the touch. Here a little pride came into her voice. So it is on you that the duty falls. Before the stranger leaves, a small boat will take you to the island of the she-hawk. To meet the concealed one.

My face must have betrayed my confusion. I had guessed, vaguely that they must know something of this more-than-woman. After all the ghost stories passed between the girls at night, it shocked me that they could talk of sailing to her island so casually.

She was—that is, she is known to us, my mother said. And then she added, I am sorry. You must…. You have to go alone. Here my cousin stepped in, and said, We need to make as little disruption as we can. But we know you can do this. My mother looked so grateful in that moment, and the other women who were there agreed: You can do this, The goddess has sent her sign.

But it wasn’t ‘til I found myself alone, shivering, beneath the awning at the rear of the small ship in the thin, first light of the day, that I began to feel worry. More than that, I was afraid. In the presence of the goddess, I had hardly cared about the strange powers the Achaean had described. But now it dawned on me that I was heading to confront something that made even my mother feel awe.

I watched the rowers. The smooth movement of their push and pull began to calm my nerves. Even alone I felt myself a part of something greater. The ship cut through the mist, between the shadows of the islands, towards whatever waited.

Even from a distance you could tell it was her island. There was something unearthly about the mist curled round the treeline. In the fading light, I heard the sound of birds and monkeys in the distance. It was enough to make even the rowers squirm.

Despite our early start, it was close to sunset when we found the bay. The winds were still all day, which the captain said was odd. We had not said much—I was too preoccupied with what lay ahead. From one point of view, my task was easy: to meet the she-hawk, and return her message. But what message that might be—and how willing she would be to part with it—I would have to wait and see.

One thing was clear: it would not do to meet her in the darkness. I shared rations with the men, huddled on the ship, and spent a fitful night underneath the stars. At dawn, the captain silently took me ashore. He pointed to a path that led through the thick woods, and put one hand on my shoulder. On the brink of saying something, he finally shook his head. Go with the goddess, he whispered. So, as I stepped beneath the dark boughs, I bowed my head to her.

No animal-men approached me in the woods, but a blue-furred monkey, of the kind my friends kept at home, ran up to meet me after half an hour. It stopped mid-path, and stood on its hind legs, scratching at its chin. Then chittering it led me up the path to the mansion.

The stranger had not done it justice in his story. This was a strong house, built in the style of Thera, but at least three times as large. I gasped a little as it came into view. The monkey looked at me, and it seemed to smile. The sound of bees was all around me as I stepped into the clearing, and walking to the door, I felt the weight of many eyes.

Waiting on the threshold, beneath a face carved in the lintel, was the mistress of the house: the she-hawk, or, the concealed one. From childhood stories, I had expected a worn crone; from the stranger’s tale, a girl not much older than me, barely come of age. She was both and neither. Her red hair was rich and plaited into heavy, snaky braids—the kind they wear on Krete—while here eyes were rimmed with exaggerated lines, just like you see in Egypt, and which I often wear myself.

Back then, these seemed to me an outward sign of strange, inner power: the burning snake hair, the all-seeing eyes. She didn’t wait for me to introduce myself. When I was a few paces from the entranceway, she called my name. The sound of it set my soles tingling, and I felt the blood draining from my fingertips. She had a power over me at once; when she beckoned me inside, past vast, open rooms towards her inner sanctum, I followed without thought.

It was only when she settled on her cushioned stool that I gasped, and regained a little of myself. Painted in white behind her were the gryphons of the mountain shrine. I knew then for sure what I had only suspected: she was one of us, a great priestess who had been sent away for some great crime against the goddess.

In my memory, this had only happened twice: young men who had transgressed her rules, and now (or so I’d heard) lived as fishermen across the green in Krete. But I knew from veiled comments that even priestesses had been banished in the past. This recognition gave me strength: whatever power she might have, the goddess had turned away from her.

Almost at once this confidence began to fade. The way she looked at me, I felt as though she could hear the smallest whisper in my heart. After all, she had known my name without my telling. As I filled with doubt, she simply waited, leaning her strong chin in her palm, legs crossed casually. It was not until I met her eye that she spoke to me. She must have read my weakness.

I see you got my message. How did my sisters interpret the signs? She laughed, closing her eyes and tossing back her head. When our eyes broke contact, I felt a little of my strength come back. She was not as beautiful as I first had thought; flat across her nose and cheeks, heavy in the chin. But then she dropped her eyes, and I stammered a reply. I told her how the goddess had shown us good favour for our care of the stranger. She smiled at the story I relayed.

Did no one question her? She asked, speaking of the goddess as if she were a little girl. Did they not wonder if it was the start of another great upheaval? She looked at me sternly, searching in my face.

What do you mean, I asked, Another upheaval? The she-hawk crossed her arms, and tightened her lips. After a long pause, she asked, You really don’t know, do you? All I could do was shake my head. This made her think awhile. At last she smiled.

That is typical of her: so scared of what she cannot control, she refuses to face the truth. I bet you never noticed all the little lies.

I did not know what to say. What did she mean by lies? And what was this upheaval? Had my mother misinterpreted the signs? Had she even willingly deceived the people, giving them false hope? After all, she had hidden the fact of my departure—just as she and the other priestesses had concealed the she-hawk from us. I tried to find an answer in this strange, superior face.

When I was close to your age, our town was stricken by the earth-shaker. Some unspeakable crime had been committed—a great trespass against the blue-bearded one—and not even the goddess (here she seemed to sneer a little) could prevent catastrophe. Houses were shaken, roofs caved in, and people died. The details were hidden from me, but it was clear from the elders’ reactions that this had occurred before. They knew of the danger, and still they had done nothing.

You think you live in a perfect world? Your city still lingers under a dreadful curse. That’s why they prune the edges. It was when I started asking too many questions that they decided they would have to get rid of me. Their world can’t handle difference, and when it became clear that I was thinking for myself, they started to plan my demise. It was only my knowledge that allowed me to save myself. Already I was wiser than the goddess herself!

I could hardly believe her arrogance! But something about her story rang true; if I thought about small things overheard, and the way that certain roofs still showed the signs of similar repairs, I could believe that such a giant earthquake could have happened.

At the same time, I had the feeling that she was speaking a little slant. There was more to the story of her exile than she let on. How can I put this? Already, I had the sense that the two things she had described—the earthquake and her banishment—had to be connected.

She seemed to sense my challenge. I do not tell you this so that you will think better of me, she said. Her words were betrayed by her terse tone. Instead, consider this a friendly warning. I can see you are a girl of huge potential. I will pass on the true meaning of the sign to you. All I want is for you to know the truth of your people—so that, when you return, you don’t find yourself… compromised.

The earth-shaker’s anger towards your people has been re-awakened by the stranger from the sea. He is a criminal, an animal, fit only to be sacrificed. Perhaps if you had done as I had tried to show you, and offered him up as a gift to the sea-father, then his anger could have been turned away. But you have done the opposite. I can read the signs engraved in your heart. You chose the goddess. So, before the season ends, the goddess will be brought low from her mountain shrine and all of your great town shall be swallowed by the earth. The island has been claimed by the sea.

At first I could not speak. I stood rooted to the spot, the life drained from my legs. Then, as if I had been stung, I shouted out, You lie! It was the only response that I could muster.

She stood up so quickly I could barely register the movement. Her hair tossed up and down around her, and her eyes held me in place. You dare to question me? She hissed. After I show you such kindness? You have brought this on yourself!

She had drawn back her hand as if to rake me with her claws. Feeling all the world slow down and grow still around me, I listened. This time, I summoned the touch. I felt the rippling in my spine, the tension in my neck. In a voice no longer my own, I spoke.

It was you who brought the last upheaval, she-hawk. Like me, you had been chosen, picked to stand apart. But you went too far—you thought, no doubt, that rules did not apply to you. I don’t know your crime, but I can see that, for all your arrogance, you still hate my people. For all your power, you are goddess of nothing here.

I see it was no goddess, but you who sent the stranger to our. You did this not from kindness, but from hate. If the earth-shaker has sworn to destroy our town, it is your evil that has caused this, no crime of ours.

I will take this warning with me, and do what I can to turn away disaster. But know, she-hawk, that from this day your power is broken. No one will come to you in supplication, no one will even whisper your name. You are empty now: a cicada’s shell, an instrument for the wind.

The strength ebbed from me as quickly as it had risen. As I was speaking, I had felt as though I had been floating from the earth. Now I felt deeply grounded—as if under a great weight. But as I tried to straighten up and gather my breath, I saw that my words—mere guesses, drawn together in the heat of desperation—had still managed to find their mark.

Her glamour was broken. She was concealed no more. The smooth skin across her cheeks and beneath her eyes had darkened and begun to sag. The life in her body was gone, as though she were the skin of some long, red-gold snake sloughed off, ready to crumble. She panted, collapsed on her seat, and once I turned my back on her I never took a second look.

Yet I could not block out her words. With a rattle, she croaked out a final prophecy as I strode from her house. You can warn them and be safe, her husky voice cried, but you will never have that wholeness again. You cannot stop the fractures, and all of that togetherness will fall apart.

Whatever you might say about the she-hawk—and these days, true to my word, I do not say much—from her empty throne she still spoke the truth. The first tremors shook the town just as our ship was sighted on the horizon.

Everybody took this as a sign of harmony. The people poured out from the workshops, down into the harbour, and a return that should have been solemn was upended into joy. Someone hung a chain of crocus flowers round my neck, and the cheering and singing was so loud that I could barely think.

Through the throng, I said nothing. I walked to the high tower, up the sacred staircase, and made my way up to the station of the living goddess. Though I had told them nothing, the rowers and their captain must have read more in my looks than I had imagined. The formed a guard around the entranceway behind me. I felt, as I ascended the cool, silent staircase, that a wave was rippling outward through the crowd. By the time I stood in my mother’s station, the whole town was quiet. When I spoke, my voice would carry everywhere. My words could not be taken back.

I don’t know what I had expected after my speech was done. Maybe I was waiting for someone to cry out, call me a liar—to contest my words, the way I had challenged the she-hawk. It was almost too large a truth for me to speak—the town must be evacuated, for the earth-shaker had promised to destroy it.

But nobody called out. Nobody challenged me. From the way the older men and women nodded to each other, a strange calm in their expression, I knew that a large part of what I had been told was true. They had been waiting for another visitation from the sea.

It was then I backed away, out of sight of the crowd. Wrapped in the cool darkness, I felt tears run down my cheeks—felt myself bend over, sobbing silently. Only then did I understand. I had been hoping that someone would tell me I was wrong. I longed to be wrong. I shuddered then, not with the touch, but the memory of the she-hawk’s final words.

Every time I felt another rumble, I would climb up to the roof of our house in Krete. I would gaze across the great green, towards the shadow of our home. On clear days, when there was little haze on the horizon, you could make the peak out clearly. So I kept a lonely vigil, measuring the height against my memory, hoping that I had misread the signs etched in my heart.

At first I was convinced that the curse would never hold. We worked together to gather up all of our tools and treasures, sailing them in convoys to the island of Minos. The king of the twin-axe was more than happy with our presence. Long had the people of Krete treasured the clothes, the tools, the art we made. Our strong heartbeat still pulsed in time, as we established new workshops and a new community amongst the bull-lovers.

But, bit-by-bit, it started. First it was a few young men, too proud in themselves. They sailed back to the empty town and began to repair the damage from the tremors. When, after a week, they did not return, my mother led a party to gather the truth. She gathered their bodies instead, curled up and putrid with some strange poison.

After this, some of the middling craftsmen, who would never rise to the head of their workshop, began to take up posts with great ladies and lords of the house of the twin-axe. Others followed their lead, trickling away to the smaller palaces that dot the wide island.

I bore my new burden better than the first. You see, I could not speak the curse. All that I could do was practice my painting, and let the goddess guide my hand. I waited for the sign.

When I saw the painted eyes of the Egyptian embassy, I knew the time had come. It made it easier that they loved our work. I took aside a princess, one of the ambassadors, and with the little of her tongue that I had learnt, told her of my desire. It was not hard, once they had made a formal offer, to convince the remaining priestesses. Now our numbers were diminished, it was easy to collect our lives again. Our rowers were proud to keep pace with the bright Egyptian ships.

The first night out, I could not sleep. We had put in to a harbour at the eastern end of the island. Stepping out into the moon, I felt a great stillness. All my life, I had found peace in her light. That night, for just a moment, she made everything calm, silver, and perfect. All the world was one great whole. Then silently, I felt the ocean slip away. I felt the whole world tremble, felt the earth give a great shudder. In the distance, I saw the first bright flashes in the sky.

Nowadays, I don’t like to dwell on memories like this. It’s hard to think on life before the stranger from the sea. But when my mother weaves her word-spells in the twilight, I give in with pleasure.

I find myself perched on the topmost house in Thera, nestled like a young skylark with the whole town before me. I see her in her robes again, proud on the high terrace. She makes the holy gesture to welcome in the ships.

Then her words make me a seagull. My breasts skim the waves towards the stately line of ships and I wear the wind like a sheer slip in early morning: cool and loose and free.

Suddenly, and all at once, they’re there—the high sides painted with their many-coloured dolphins, the awnings and the sails billowing and rippling in echo of the water. The tillers all stand to attention and the captains stand in their tents surveying, like little princes, the ranks of deep-bronzed men who heave the oars as one strong heartbeat.

In one or two ships, the oldest hands sit under covered awnings. The others who have served their term are gathered on the shore. They wrap themselves in rich cloaks, their badges of honour, and talk quietly with those old friends with whom they shared the bench. Though there is no disgrace in being past the age of rowing, yet you can see the gleam in every eye in every group: they feel the great call—they long to be part of a whole again.

To start with, though, you can’t quite grasp the mystery. I know for a long time I found the day unnerving. The priestesses—those who judge, who lead, who weave the word-spells of our people—they take their appointed places. For many of us children, these were also our mothers, our teachers, our friends.

But when they appeared to us in those dresses tiered in alternating bands of saffron and lapis lazuli they were also something more. They became the great goddess, the holy spirits painted on the walls in every sacred house. On those days our noise would quiet, and we would let ourselves be led by the chosen guide, as silent as goat-kids when a storm sounds in the distance. Hushed and not quite understanding we would go down through the streets towards the harbour. Oftentimes, the guide was someone I knew well: my aunt, perhaps, or even an older cousin. But never my mother. She had a different role to play.

The year the stranger came, I was nearing thirteen. So, for a long time I had worn this difference like a second skin. No-one had to tell me any more about the things I could not do.

The worst had been the boxing. Here in Egypt they think it strange if girls do any exercise at all, but back in Thera, not only did we take on the boys in the yearly games, but normally we won. And in the midsummer celebrations, when the days reach their longest, we would end the festival with boxing between the nimblest girls, the best of those who had not yet passed through the rites of the great goddess.

Like me, their heads were shaven, save one lock at the front, and a long braid at the back. It was agony to cheer along for two of my best friends. They danced around each other in the last light of the long evening, young lionesses pawing at one another then tumbling away. To know I could have won—could have danced in that adulation—and yet to say nothing, to bear them no unkindness, to cheer with all the rest: that was heavy on me.

If something less was dealt for me, then there was also something more. When the time for our flower harvest came, I knew already that whichever of my friends composed the chosen song, I would be the one to lead the ceremony, the one to sing the spell. It was my job to be a vessel. I had to let the others fill me up, and let the great goddess transmute me as she will. One day, when my mother has gone, I will do the same for all my people, wherever they might be.

The year of the stranger I felt the burden more keenly than ever: this was our year to go up to the fields and collect the saffron, to offer the great goddess the bloom of one flower in exchange for the blooming of another. From then on, we would grow our hair out, cutting off our forelocks to present the goddess with those basketloads of crocus stems.

I knew some girls might start to swell with my responsibility, casting a shadow over all the rest and everything they did. But I had watched my mother well. Soon I found that the more I drew myself back and allowed myself to open, the more the others turned to me to lead.

That day, before the feast of coming home, we were given the holy garments to prepare. This was a little test, and we shared the tense excitement that came with our permission to play a greater role. Little goats no longer (or so we saw ourselves) we rose before the sun and picked our way down to the harbour with the naked fisher boys. At a crossroads, I stopped.

Later, when the great priestesses asked me about this moment, I found it hard to tell them exactly what I felt. After all, it was only the second time I had felt the touch. Now I am older, and am a little closer to the mystery, I can describe it to you a little better, or at least, less badly.

As I said, back on the island we girls would play at all the same games as the boys. Though we did not take to the boats and bring back lines of fish as they would, when the skies looked ill all of us would go together to certain little coves and dive for octopus.

In Egypt, where they look for the raw strength of the hippo or the crocodile, it is hard to convey the magic cunning of our mottled quarry. The way she wraps the shadows around her, or shifts her colour to hide against the rocks. Every one of us had known her blast of ink, and the surprising strength in her soft, thin arms. Half the trick is learning to control your breath. You need to make her curious: diving down before one of the caves in which they make their dens, and hovering above the sand, perhaps blowing out a slow stream of bubbles. You need patience and calm, waiting for the sign—that first curious arm. The boys prefer to use a spear, in practice for their days aboard the ships, but I liked to use my hands. That day I was glad I did.

Looking back, I can see it was the first time I felt the touch. But I had been waiting at the bottom for too long—maybe that is why I didn’t dwell on the strange feeling too much. It was too mingled up with the signs of half-drowning.

We all had shared the sight of the blackness drawing in, as if we had been squirted with ink from either side. That day I knew I was getting close, that I could not risk staying much longer, but I could see the arm drawing further out. It promised an octopus of enormous size. When the feeling began to fade from my finger tips, I had to make a move, so kicking off the seafloor, I made my lunge, aiming for the space between her body and the cave. The octopus, blocked off from her den, shot off into the bay, contracting her great mass through a tiny crevice.

Normally, that would be all; I’d rise up to the surface, draw in the sweet air, and let the others laugh or console me as they like. But I felt a shudder. It ran through me, a bright surge that set me trembling from the tips of my numb toes along my spine up to my scalp, pricking up my forelock like a startled cat.

Although it felt a lifetime, hardly a second had passed and, knowing that I must, I kicked off from the rocks and gave chase over the outcrop out into the bay. By now I really was losing my sight to shadows, but I could still make out her dark form jetting across the sand. She came up short before me, arms wrapped around a dark shape in a spot to which we had never dived before. I fumbled forwards, felt for the thing, and hauling it beneath me, kicked my way up to the surface. I don’t remember reaching air; apparently I breached the surface like a dolphin dancing, then settled on my back clutching the enormous vase.

For a vase it was. It was painted in a style that to my eyes seemed ancient. When we brought it back many of the elders could recognize its type, though none had seen this very piece before. All marvelled at its design. One side showed dolphins swimming around our island. The peak was obvious, with the goddess’s sanctuary and her sacred throne. The other showed a woman who could have been my mother. She had been drawn in thick lines that seemed to throb with power. It was the goddess, one arm to her chest, the other extended out in the gesture of welcome. All took it as a great sign, and for weeks I felt the whispers that rose up in my shadows. I was my mother’s daughter indeed.

The day of the stranger, I felt the touch again. Each of our little troop was laden down with piles of the sacred skirts. But when the boys turned off toward their low fishing boats, I paused. Something about the orange light stretched out across the ocean in rolling lines of mist made me turn towards the east. And then I felt it, rising up my calves and coursing up my spine. I felt my scalp tighten, my long ponytail rise, and my shoulders tightened drawing up my chin. The other girls had fallen silent. When I led us east, away from the bay where we usually washed up, they did not question me, or raise their brows to one another. They trusted.

Still, it did not settle well in me. To try and shrug the worry off, I called for a ball. It’s still the same, even now that we have made our home here: ask any group of Theran girls for a ball to toss, and out will fly a dozen. Before I knew it, we were laughing, trying not to spill our bundles as we tossed and kicked the toy between us, clambering over the rocks towards the reedy bay.

We didn’t go there often. A little spring from on the mountainside made its way down to here, but it used to have an air of secrecy about it. You heard that lovers would meet there for a private tumble; I was not surprised to see two of my friends glance sidelong at each other. You could tell they had the goddess in their eye. She was with me too, that morning, though she played a different role. For between the beds of rushes, naked and bluish-white, lay the broken body of the stranger from the sea.

On other days the other girls would talk about the angles of his legs. You could feel the way his very bones seemed to wound him. Sometimes it was the dead-fish colour of his skin that they remembered, the look you see on drowned men when they wash up days after a storm. It was easy to forgive the others for believing he was dead. And for a few, those with good humour, it was his hair that stayed with him.

Of course we had met Achaeans before; they often came to trade with us, and a few families now had a touch of the golden hair of these north men. But we did not expect to see the pelt that sprouted from this man. His legs were thick with golden bristles, and the thatch around his sex ran up his belly into a deep forest on his chest. Even after we had helped him to recover, he did not shave his body as our men and women do alike, but kept it as thick as the beard we always saw him wear. Only above his lip did he run the razor, and even then, my friends whispered, only to make the beard show thicker.

What I remember, though, more than his storm-wracked body, was the spirit around him. It called to me. Where the others at once believed him dead, drawing back so as not to contaminate the holy robes, I sensed a will to live. I put aside my bundle, and touching my fingers to my temple, felt an echo of the shudder. Not for nothing had we half-drowned ourselves in search of octopus: I knew at once how to expel the brackish water from his chest, to pump sweet air back into this almost-emptied husk.

At last, he spluttered up the final burst of brine, and with my help pulled himself up the beach to lean against a rock. Almost as surprising as his rough, animal pelt was his embarrassment at exposing his sex to us. This was something new, and it puzzles me still: how one can feel ashamed of showing what we all know is there? At least in Egypt, no one minds about our open dresses. Many Egyptian girls wear as little as the bull-dancers on Krete. I wonder how my friends survive who made their way to Ugarit or Hattusi, where they have to wrap themselves in a dozen layers. At any rate, I soon convinced him to borrow one of our shawls, which he wrapped around his waist. He thanked us in a cracked voice, and summoning his formal speech, asked us where he had found himself.

The other girls had shuffled back. This was my role. I spoke for all, but stood apart. He did not recognize the name of Thera but when I described it as the first island north of Krete, his eyes widened and he nodded.

Those green eyes, they seemed to ask me more—perhaps more than I could tell. His ship, his crew: of these I could not yet describe the fates. But as a stranger, he was due all that I could give. So I gave him my name, which he echoed softly back, like the sea when it is caught inside a shell. I told him where to find the great house, how he should approach my mother, the way he must address her. All this he took in as a parched man takes in water: thirsty for kindness.

Before he made his way stumbling up toward our town, he gave me something in return: his own name. Its foreign cadence sounded strange inside my mouth, and I saw the look that darted round the girls when they all heard it. To us, his name sounded exactly like the word for “one who is lost.”

Even close to death, he had a honeyed tongue. He could not tell, he said, whether I was goddess or mortal. At this I felt a knowing look shoot between my friends. It quickened something in me, too, though of a different kind.

Once we had seen him on his way, they asked me why we had not helped him to the town. After all, his limping steps showed how weak he’d grown. I told them that the goddess had sent us there to give help to a stranger, and in return we ought to do her service to repay her. We have these robes, I added, let us not neglect our task.

I did not tell them that I was afraid of what might be said if I passed through the town with my arms around a stranger. So close to our flower harvest, it could prove an ill omen to be seen so close to one of such great spirit—especially if he were overheard making comments like that!

As it was, when we came back into town that evening with the skirts and robes prepared, we felt just like a party returning with captured pirates. I had let the others gossip as the clothes dried in the sun; it could do no harm to wonder at his. My own curiosity was as sharp as theirs.

Something about the way he collected himself told me that this was not the first time that the goddess had delivered him from danger. He even seemed to look at me as if with recognition. It does no good to work over thoughts like this too long: like dough, with too much kneading they grow thick and heavy. So we brought out the ball again, and gradually I turned the conversation to the coming festival. But all our minds burned with a quiet pride as we returned: surely it was a good sign to rescue a stranger before the feast of coming home. After all, that is a day when everyone becomes a stranger.

In the days that followed, I could not help but wonder if that pride had played a part in what took place. The others told me later how they had seen it unfold, and though I could place myself amongst them in my mind, I still catch myself, on black days, wishing I had really been there—as if my presence could have averted the hand of the goddess!

As usual, the night before the feast, each rower had taken his leave and put on a different face. With the evening tide, they had sailed round the island to the harbour-village to the north. As usual, in the morning the youths had all formed into their chorus by the shore, waiting for the arrival of their stranger-family.

No weaving, no painting, no turning pots the day before. Everyone who was not putting on a different face had come together to prepare the welcome feast. Now this was brought out with solemn song to the benches in the square outside my mother’s tower. As usual, she stood proud on the topmost roof in Thera with one hand to her breast waiting to welcome in the strangers, make them family once more.

I did not see it happen. The whole day I waited with the stranger in the shallow room of offering, which in the sacred house sat below the level of the other rooms. It was cool and silent: here I tended to his fever. He had survived the journey to the town, even his audience with my mother, but as night fell the heat rose in him, and though his ribs showed that he had nothing left to give, still he had retched and hurled while the heat raced over him.

I knew how to prepare the poppies, and with their vapours I eased him out of the worst of his struggles. For a long time I tended to him in this half waking slumber, sponging his burning body, tending to his twisted limbs and raw patches of skin with herbs and clear spring water. He seemed to me to be somewhere on the doorstep of the underworld, and several times he broke through the mist of the seeds and called out fearful names—the kind that seemed to come not from our world but that place the Egyptians know so well, where strange creatures emerge from the darkness in monstrous, hybrid knots.

One name was different: when he sounded it, I heard a mixture of desire and loss. It was the name of the she-hawk. Each time his spirit seemed about to depart at last, he would heave his chest and cry this name aloud. It was as if he saw her, circling around his head. And so it was, between the cool silence of the room and his flaring bursts of heat, that I passed the feast day and missed the turning of the tide.

It happened as the first boats began to draw close to the shore. The captains urged their rowers on; the other priestesses called out welcome to the strangers from their allotted balconies. As my friends described it, I could feel the crowd swelling with excitement as if I was there. Bur my mother remained silent as she always did. The goddess was in her. All the signs were good.

Suddenly and without warning the sea began to draw back from the shore—not as the tide does, in slow rolling waves, but like a blanket pulled back from a bed, a rapid jerk revealing long stretches of sand. They told me you could see the crabs—suddenly exposed—racing to find shelter. Several boats were pulled back, far out into the sea, while the leading ones were beached, still too far from the harbour.

At least some of the men managed to keep their cool. Remembering those stories of colossal waves that all the traders know, they quickly leapt down to the shore and, shouting to their teams of rowers, hefted up two of the smaller boats together as best they could, trying to manoeuvre them to higher ground. The other ships they had to leave in the goddess’s hand. On the shore, though, everyone was thrown into a quiet panic.

It was not the first time that we had been shown displeasure: it had rained one year, while two men drowned another. Dark skies, rough weather, or ill-birds they could understand. But this was beyond thinking. Only my mother saved the day from falling into chaos. In that clear, bright voice that I have not yet learned the trick of, she called out over the crowd, stilling them just a word.

She began, This is a day when we remember what is due to the stranger. We put on a foreign face and show that this makes no difference. Everybody here knows our bargain with the goddess: so long as we show proper service to those strangers she throws our way, she will protect our own, and bring them safely back to our shores.

I could picture how these words must have stilled the crowd. When you are used to ceremony sometimes you forget the sacred pact.

She continued, Yesterday, as many of you know, she sent another stranger to our island. His body bears witness to the dangers of the ocean, which all who sail on the great green must understand too well. Did we turn him away? Did we ignore his wounds? No. We welcomed him as if he was a brother or a son returned from some great travels. So, did you think the goddess would not pay heed to our service? She draws back the ocean now to show her power over the sea-father. Look at those plains of sand, hidden for generations. If she can reveal them in just an instant, then surely she can protect us from a sudden wave or tempest? So rejoice! See, even that great wave that the earth shaker might have sent as retribution, she has turned this away.

You can imagine how they feasted after this. Once the remaining boats had been brought close to the harbour, the tables were moved down onto the open shore and my mother led the celebrations from an impromptu throne that the men assembled from some of the boulders that now lay exposed.

In the sacred room, I had little sense of passing time. It caught me by surprise when she came to me at last, and told me the feast was done. She spoke to me as if from a great distance, and when she stroked my forehead it felt as if even her touch was somehow remote. By now the Achaean had settled into a deep sleep; still, my mother asked to take over the tending.

She told me a little of the strange events that day, leaving others to indulge in the dramatic detail, and told me where I could find a little food that had been set aside. As I turned to go she caught my wrist.

Did he say anything, she asked, did he call out through the darkness? She listened deeply, and even with her granite composure, I saw her start when I mentioned the name of the she-hawk. She whispered something to herself. My wrist still in her grasp, she fixed her eyes on me and said, Do not sleep this night. Meet us at the shrine with the first light of dawn. I must convene the others.

You could not be a girl on Thera and not learn, somehow, of the concealed one. Sometimes she was the unnamed threat a mother whispered to her daughter: a monstrous beauty wreathed with snake-hair, whose tribute was those girls who misbehaved.

Other times, from the reverential tones in which the priestesses talked about her, you might think she was the goddess-on-earth. It was when an illness came that was beyond the aid of even the oldest mother, or when there came an omen impossible to understand: those were the times that she was mentioned, and an envoy would disappear at evening, sailing towards the east.

As I waited on the mountain slope, watching the web of stars slowly turn above me, I grew more confident that it was her name my mother had whispered. How the concealed one related to the she-hawk, though, I could only guess. I shivered in the dark.

When the first ring of pink light edged over the horizon I stood up, stretched, and made my way up towards the peak. As I had expected, every priestess was there, breasts bare and hips laden with three- or four-flounce skirts. They lined the pathway to the throne, which had not caught the first light yet.