Curtains fluttering, sailing over the sill. Nonna’s voice singing a lullaby. “Ninna nanna, ninna o, questa figlia a chi la do?” Margaret stares drowsily into the light at the floaters drifting and darting before her eyes. Ghostly specks of prenatal detritus. One of them, knobby as a seahorse bobs up and down. She tries to hold it in her eye and make it stay still, but it won’t stay still. And from the kitchen of the little second-floor apartment Nonna calling, “vieni, vieni,” motioning, “come, come” to the table. The scent of coffee and burnt toast.

Maybe today they will go for a walk. She and Nonna will go hand in hand and Margaret will jump over the cracks in the sidewalk. Or maybe they will color in her coloring book; and when they get done, she will fall asleep to Nonna's lullaby:

“Ninna nanna, ninna o, questa figlia a chi la do?

“Se la dò alla Befana, me la tiene una settimana…”

Still at the window Margaret stares with the uninterrupted focus only a small child can manage. Large blocks of color - a green rectangle of lawn, the white glider-swing and hydrangea “snowballs” of intense blue - imprint themselves on Margaret's mind.

“Vieni, vien'a mangiare.” Nonna calling.

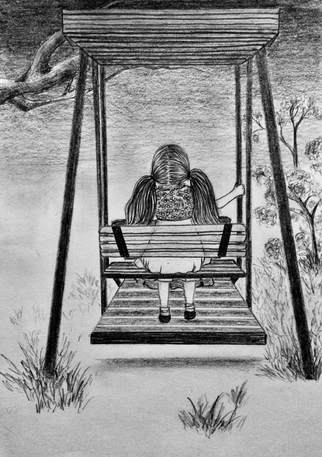

Another girl, maybe five, maybe six, has entered the garden below. A beautiful child, luminous and inevitable as a fairy-tale princess. Honey curls spilling over her sunlit dress. She swipes dew from the grass with the toe of her shoe. Rosalie, yes, that's her name, making an arc of dark green in the grass, and then footprints tracing her path across the lawn to the glider swing. And Margaret at the window mulling the mystery, always alone, that nice girl with no one to play with, why? Longing to go down, longing to swing in the glider swing.

But how would Margaret get to the garden? To turn from the window, to lose sight of the garden, to move deeper into the house in order to use the stairs would be counter-intuitive, so the garden remains unattainable.

Rosalie swinging back and forth inside the glider. All by herself. The empty chair on the opposite side. Forward and back along a flat plane. Unnatural not to swing in an arc. Why doesn’t it swing like swings in the park?

And Margaret imagining herself on the empty side of the glider. “Do you want to be friends?” she would ask... If she knew how to get there.

Beneath Margaret’s window the downstairs screen door sweeps open. An old woman’s head, hair pulled back in a bun, turning to look at the glider, turning like a globe hovering above a rippling shawl. The landlady named, Etsò. The house belongs to her. The house and the stairs and the garden. Rosalie belongs to her, too, the grandmother, Etsò, so nick-named by Nonna.

“She gives that poor child just so much to eat and et sò!” Nonna draws a line in the air, to signify that’s all! “

Ignorant woman! It’s illness that bloats the child’s stomach, the Mediterranean illness.” Nonna leans over Margaret’s head, and looking down from the window sourly while stroking Margaret’s dark hair.

“She thinks her granddaughter is fat, so she starves the poor child. The povera creatura begs for food and all she says is, ‘Et sò!’ Maybe she thinks she'll starve the disease out of her! Her heart is a piece of coal.”

The evil Etsò still under the window. The hem of her dress fluttering about her ankles. A black silk dress. White hair. Enigmatic as a photograph negative. Summoning Rosalie, her bent finger beckoning. Rosalie, leaving the swing, crossing the yard. So pretty how could she be sick? Etsò’s arm reaching out from the threshold, shepherding Rosalie as the child disappears inside, and the screen door closes.

Maybe today they will go for a walk. She and Nonna will go hand in hand and Margaret will jump over the cracks in the sidewalk. Or maybe they will color in her coloring book; and when they get done, she will fall asleep to Nonna's lullaby:

“Ninna nanna, ninna o, questa figlia a chi la do?

“Se la dò alla Befana, me la tiene una settimana…”

Still at the window Margaret stares with the uninterrupted focus only a small child can manage. Large blocks of color - a green rectangle of lawn, the white glider-swing and hydrangea “snowballs” of intense blue - imprint themselves on Margaret's mind.

“Vieni, vien'a mangiare.” Nonna calling.

Another girl, maybe five, maybe six, has entered the garden below. A beautiful child, luminous and inevitable as a fairy-tale princess. Honey curls spilling over her sunlit dress. She swipes dew from the grass with the toe of her shoe. Rosalie, yes, that's her name, making an arc of dark green in the grass, and then footprints tracing her path across the lawn to the glider swing. And Margaret at the window mulling the mystery, always alone, that nice girl with no one to play with, why? Longing to go down, longing to swing in the glider swing.

But how would Margaret get to the garden? To turn from the window, to lose sight of the garden, to move deeper into the house in order to use the stairs would be counter-intuitive, so the garden remains unattainable.

Rosalie swinging back and forth inside the glider. All by herself. The empty chair on the opposite side. Forward and back along a flat plane. Unnatural not to swing in an arc. Why doesn’t it swing like swings in the park?

And Margaret imagining herself on the empty side of the glider. “Do you want to be friends?” she would ask... If she knew how to get there.

Beneath Margaret’s window the downstairs screen door sweeps open. An old woman’s head, hair pulled back in a bun, turning to look at the glider, turning like a globe hovering above a rippling shawl. The landlady named, Etsò. The house belongs to her. The house and the stairs and the garden. Rosalie belongs to her, too, the grandmother, Etsò, so nick-named by Nonna.

“She gives that poor child just so much to eat and et sò!” Nonna draws a line in the air, to signify that’s all! “

Ignorant woman! It’s illness that bloats the child’s stomach, the Mediterranean illness.” Nonna leans over Margaret’s head, and looking down from the window sourly while stroking Margaret’s dark hair.

“She thinks her granddaughter is fat, so she starves the poor child. The povera creatura begs for food and all she says is, ‘Et sò!’ Maybe she thinks she'll starve the disease out of her! Her heart is a piece of coal.”

The evil Etsò still under the window. The hem of her dress fluttering about her ankles. A black silk dress. White hair. Enigmatic as a photograph negative. Summoning Rosalie, her bent finger beckoning. Rosalie, leaving the swing, crossing the yard. So pretty how could she be sick? Etsò’s arm reaching out from the threshold, shepherding Rosalie as the child disappears inside, and the screen door closes.

***

November. Margaret again leaning out of a window. The parlor window this time. The one overlooking the street. Beneath her, long purple ribbons snapping in the wind, cracking like whips from the wreath on Etsò’s front door. On the street two black limousines passing slowly. The sun flashing in shafts from the windshield, the roof; the windshield, the roof. Passing the house, saying good-bye. Nonna leaning out of the window beside Margaret, explaining. That strange word, veglia, on her lips.

Wake? But how? Nonna said Rosalie had looked like a princess asleep.

And Nonna describing, “Her pale cheeks were rosy and her lips, red as rosebuds. For first time in her life. So beautiful in her coffin. And her stomach, perfectly flat. It was death that cured her. Rosalie is safe in heaven now,” Nonna informs. “Safe from Etsò forever.”

The news of Rosalie’s death and her miraculous cure drops gently upon Margaret’s mind, banking and settling, leaving its mark, the way a fallen leaf stains a sidewalk. She imagines her would-be friend, a rose in a field of children-turned-roses adorning Mother Mary’s throne. This last, an image she recalls from a holy picture sent by an orphanage in Italy.

Margaret, leaning into the wind. Morning sunlight, morning wind. The procession beneath her, the wreath on the door, all taken in, simply, without judgement.

But later that day, at sun-set, Margaret's eye is caught by the kitchen window which is a plane of blazing light. Through it, she sees a cloaked figure enter and drift like a shadow across the backyard. It stops beside the glider swing. Etsò. Raising her shawl to her head and drawing it about her body. The afternoon wind ruffling the long, silk fringe of her shawl, rattling the dry hydrangeas beside her. Margaret, at the window, holding the old woman fast in her eye.

Etsò faces the day's dying light. Stands like an obelisk against it. Then, without warning, the old woman’s hands fly to her face. Her body crumples and falls. The black shawl and skirt billowing over the ground like curled layers of char.

The sight sends a spasm of fear though Margaret's heart. From then on a troublesome image will drift in her memory. Like a sloughed cell or floater, prenatal, perhaps even more ancient. And in the tales she will hear but has not yet heard, the Hag will terrify her and thrill her as well, though she may not suspect the source that sustains it.

Wake? But how? Nonna said Rosalie had looked like a princess asleep.

And Nonna describing, “Her pale cheeks were rosy and her lips, red as rosebuds. For first time in her life. So beautiful in her coffin. And her stomach, perfectly flat. It was death that cured her. Rosalie is safe in heaven now,” Nonna informs. “Safe from Etsò forever.”

The news of Rosalie’s death and her miraculous cure drops gently upon Margaret’s mind, banking and settling, leaving its mark, the way a fallen leaf stains a sidewalk. She imagines her would-be friend, a rose in a field of children-turned-roses adorning Mother Mary’s throne. This last, an image she recalls from a holy picture sent by an orphanage in Italy.

Margaret, leaning into the wind. Morning sunlight, morning wind. The procession beneath her, the wreath on the door, all taken in, simply, without judgement.

But later that day, at sun-set, Margaret's eye is caught by the kitchen window which is a plane of blazing light. Through it, she sees a cloaked figure enter and drift like a shadow across the backyard. It stops beside the glider swing. Etsò. Raising her shawl to her head and drawing it about her body. The afternoon wind ruffling the long, silk fringe of her shawl, rattling the dry hydrangeas beside her. Margaret, at the window, holding the old woman fast in her eye.

Etsò faces the day's dying light. Stands like an obelisk against it. Then, without warning, the old woman’s hands fly to her face. Her body crumples and falls. The black shawl and skirt billowing over the ground like curled layers of char.

The sight sends a spasm of fear though Margaret's heart. From then on a troublesome image will drift in her memory. Like a sloughed cell or floater, prenatal, perhaps even more ancient. And in the tales she will hear but has not yet heard, the Hag will terrify her and thrill her as well, though she may not suspect the source that sustains it.

The End

Lullaby translation:

Ninna nanna, ninna o, questa figlia a chi la do?

Se la dò alla Befana, me la tiene una settimana…

Lullay, lullay, to whom will I give this child?

If I give her to the witch, she will keep her for a week…

Ninna nanna, ninna o, questa figlia a chi la do?

Se la dò alla Befana, me la tiene una settimana…

Lullay, lullay, to whom will I give this child?

If I give her to the witch, she will keep her for a week…

Barbara Daddino holds an MFA from NYU where she studied under E.L. Doctorow, Breyten Breytenbach, and Francine Prose. She has taught English and creative writing in the Suffolk County school system and creative writing at NYU as an adjunct. Her essays and movie reviews have appeared in Newsday and on PBS. She was also featured in two PBS interviews about late-life divorce. She is currently working on a novel inspired by her story, "Floaters," a finalist in Glimmer Train's New Writers' Short Story Contest. She lives in Shoreham, Long Island where she works in a tower overlooking the Sound. From there, it is easy to hear the hag singing.