A voice. Calling to wake me out of sleep. Asking me to think of a thing I have forgotten. Of a sigh of a man who is cursed for a burden, the cry of a woman for her child that is lost. Is it the wind whispering? Shouts of the shopmen, words blurred? From dreams drowning the morning drags me up. To hear the citysounds again, cartwheel moan and the snuff of gaslights. Noiseblend from the sootstreets, to coil in my ears.

Eyes closed. The lightspecks of dreamsleep still flashing in the darkness. What is it, the word? To my mudheavy tongue it does not come. In a language that is not mine. Glivorem: Fireflies. Yes. The rain or earth or what lit them blew them to birth. From the grass and grain and the cool stream rising, back in Volapzhin where the road to Kiev curved. In the oncoming nights, when I was beautiful. Floating in fullness past the foolboys watching.

Thirty-five years or more ago. Before the journey to this America, the deaths and might-as-well-be deaths. Such a span of time and yet still I remember. The waterlight coming clean over the roofs at dayend. To wash the roads like rain. The sun thronesitting at the streamedge, winking Godeye picking out in light the high tree leaves. You, you, I choose, not you. In the mudstreets the broken pots and chicken blood turned to gold dust and our house to polished brass, warm flameedge orange. Light burning blinding and my eyes from the synagogue the shops dazzled away. Our faces glowing beautiful, mama’s and papa’s and mine.

Misha with his rough tongue begging for scraps and the streetdogs feeling in their fur the dusk coming. Shh, the day said, like mama in her moods, shhh!, and the noises hushed. The light still strong in the high clouds but down here darkening quick to night. The world sent like a child early to bed and the parents in the daysky talking loud. And then the sun dropped down and the pink clouds faded, in the east still tipped with orange but blackening quickly west to darker deep blue winter blue. The knit of light loosening, and the stores and houses, the Dubinsky’s and the Abramson’s and the Pevzner’s, dissolving to dull grey brown. Wood boards blending and the deep ruts smoothed.

Streethouses pressed flat like flowers in mama’s book, dark rectangles and squares and then fading. Screen after screen of night dropping, blotting like Herschel’s ink. Gone the synagogue at the roadbend, grainfields distant, weeds on the streetedge. All cleaned in the pure darkness.

The black nightwall close now; only the porch left behind in the grayness. And then as if breathed up from groundfire the fireflies would rise. Mama said watch and I watched close and they winked at me and I waited again for them to wink Wink! but each time different and I did not know where they would come again or when. Before only darkness and papa’s snores but now in pinholes of light I could see the roadmud and the house across the way where Basia lived. The trees there once more for a moment in the green circles and the grass green in pieces. For hours they danced, the fireflies, rising and falling in and out like breath but no pattern.

But eyes open. Into black oceanwater Volapzhin sinks, up over housetops and spires and gone. The fireflies quenched in the darkness, green lidblots dissolving. Of a beautiful dream there is no use, if the dawn in the room is cold. Clay pots on the dustshelves, dull rugpatterns twined. A gasp of breath: mine. Jacob beside me with his snores. The whereplace returning. New York, New World. 5673. 1913. The 21st of May. Oil lamps shining warm gold, but no fireflies.

It is too much of a muchness, too soon in the morning. A rumble deep in my head. Hoofbeats? Fistgrasp at my breath. The burnflush rising. But it is only little Avrom, mouth open stirring in the cradle. The street outside is calm, buildings unburnt. No high whinny of horses, crack of hoof on wood before the splintering. I rise from the bed, feel the rough ridges of the planks against my footsoles. My eyes can see in the darkness: the stove, the cradle. In Avrom’s ear I whisper soft in English. His legs fat like his father’s kicking against the night. He will know more than me, more than Lea, new language and old stories too. But English is hard, a glove that does not fit. Always another finger outsticking, no cloth to cover. And dreams the hardest; at night the books the signs in Volapzhin still in Yiddish or in Kiev “ні євреї.”

Still three hours till the dawn, but a change in the thickness of darkness. Enough to see the patterns of the wallpaper, the wood table with faded brown cloth, marked by the old lines of Lea’s school ink.

A flash of white on the pocked woodfloor. Reflecting for a moment the moonlight. A square of paper, half-tucked beneath the apartment door. It has been slid there, in the night. I stoop to look. Left top corner crumpled, greyed by dust. It is a knife: to cut my breast with its edges. Telling me I am not safe. Notes can be slipped in secret to me: threats. Robbers can scale the buildingsides and pry back the windowframes. This room is nothing. I press my hand to the door. Strong and solid it seems, but it is like the curtain walls at the theaters, letting through light and anything. Who else will come with their words to wound me?

But it is from Lea. I know already. I unfold the creases of the paper. Scrawled inside is her child writing: the looping g’s and unsteady d’s. I am coming to see you tonight. It will be good for us to talk.

I am the you she is coming to see. Not Jacob, still asleep. Did she drop the letter off with Mrs. Teplitsky? Or in the silent hours of night creep up the stairs to place it here herself? I press myself to my feet, my knees aching. Always now I can feel my bones and body that before were light and nothing.

I watch Jacob, his chest swelling like sea waves before the break, swaddled in the red and purple coverlet. He knows of this. They have met in secret. Planned it all. Conspiring against me.

America has made them weak. Lea has learnt nothing. At her age I had lived two lives for her one. Soaring I had come in birdflight across miles and countries, plains of Kiev to the valleys of Wall Street. A continent and an ocean. In horse-cart and steerage. She does not know hunger, like I know. She does not know the struggles and the sufferings, or the happinesses that were. And so she did not listen. Meeting with the nogood men after the sweatshop sewing that I had not wanted for her to do. Already I had begun to suspect: that little fatness around her middle. “What have you been eating?” I asked. “The look of you—it is a power you should not lose.”

It was over dinner; cabbage and kasha. “I am pregnant,” she blurted, her elbow striking the tableside hard.

Jacob blinking as if it waved the fact away. “What?” he cried. “You are to be married?” The innocent.

She pouted, face red and angry behind the tears. “He has run off.”

“The swine!” Jacob cried.

“And you did this with him?” I asked. “One of these American shysters you love so much? On about his money and his plans, ‘you are more beautiful than the Gentile girls’?”

“No, mama. It was not like that. He was …”

“I do not want to hear of this filth. You are a shanda.”

“Minna…” Jacob’s hand on my shoulder, trying to stop my feelings, as he always does.

Lea’s face was blank. Dead.

“Go, go,” I said. “I am used to this. You will leave me anyway. It may as well be now.”

The fire was bright in my eyes and my breath short. But the words were not quite right to say what I wanted.

“I don’t understand,” Jacob said to me, his face open in appeal. “She is not asking to leave.”

But she had thrown away what we have given her. For Jacob in Volapzhin said, “we want a better place for our children. We must go to the New World.” So: the town gone and mama and the horse heaving its dying sighs and Jacob choking down his shame. For what? Her future now is only shame and the squalidness of the sweatshoppers we had almost worked ourselves free of. And if so then why have we endured the horrors of this world and the passage here?

“I don’t know what you want of me,” Lea whispered. “I don’t know what you want.” Like an old woman she stood from the table, unsteady.

I want this world to be Volapzhin. I want Lea to be a success but not in the ways of this America. I want the time then to be the time now. These things that are not possible.

“Out of my house, whore,” I cried. Unfaithful to my care for her.

She swayed like a tree beaten by the wind. “What? Where will I live?” She looked at me with the face of a child forced to see sights too much for her. A face I know well. And then as if shocked from the subway rails she bolted down the stairs. A silence as of breath being held and Jacob running after her, coming back with eyes like holes waiting to be filled. But he is a coward and went along.

So then a return eight months later and her bastard child forced on me. She will not stay again beneath this roof, but for Avrom who cries in the night I have relented. Now I am stuck to go through it again with this lump of flesh that wants and wants when it was done and over.

Still Jacob does not accept. Asking yesterday again, “Why is it that you will not welcome her?” He is always asking why. Wanting to talk and wonder. “It is not her getting together with the boy, is it?” he said. “Because we did too before the wedding, you remember. So, she is unlucky with the child. She has paid, she is sorry. A mitzveh it is, to be blessed with a family. It is too much for you at your age to care for a newborn.”

“What age is that?”

“We too can be blessed.” Ignoring as always.

“She is no longer my daughter,” I said.

He shrugged his hands up, breath out hot. “Why? Why this still? It is two months now that we have had Avrom, eleven months without Lea, the fruit of our souls. Is not that too long? We must take her back.”

But I sat silent. While our love was strong we lay on the edge of a sword, now a couch sixty yards wide is too narrow for us. He with his talking, over and over again, plowing the land that has been plowed. Talk is worth a dollar; silence is worth two. For why should I say or know why I feel? The same with the sadnesses that creep on me. I could say, “It is the days with nothing to do, only to sew, no books to read,” but now with teaching there is something in the days and I have the library to visit for the books. And still the sadnesses. Jacob before would sit beside me and ask, “What is wrong, my kinigl?” but I had no want to talk or to explain. It is as if they require happiness of us. To sing of this land, this America. This America that takes my daughter and my past. She eats the seeds of the fruit of this world until she is ruined for anywhere but here. Distracted by the clothes on the mannequins in the store windows and not seeing the blankness of their faces and their hands cut off.

I tell a story that no one in this New World wants for me to tell. For how can we sing songs in a world that is strange? To my mouth’s roof my tongue cleaves.

I let the letter drop to the floor. Trash for the trash she is. Words echo in my head. From the street, or in the room itself. Breath shorter in my chest. But the sounds are from the backroom only. A mumbling. I push open the door. Herschel who never sleeps sits at his desk writing. The “holy” one. Mocking me with his pages filled with squares and circles. In-law, father-in-law, bound to me by rules and power. Making words into numbers. Letters mixed with letters, picked out from the holy books. Secrets from God’s tongue only for him. Herschel whose lap as an infant Lea crawled into as if it were a better home than mine. Ignoring the urine and the crumbs.

His tongue clicks in his mouth as I stand over him. His pants are off again; his cuffs that I must wash stained with ink. The ageless legs veined blue but still strong. “Herschel, you must sleep,” I whisper, but his hands move on unchanged. All this for nonsense, and his mouth always hungry to be fed. Herschel who people called the wise but who when I was a child in Volapzhin was only a strange one to be avoided. “He is thinking deep thoughts. Thoughts of God. Not for us,” Papa said.

But why I thought should God not speak in our language but in words that made no sense? For all day through the town Herschel in his long black coat looked up at the sky or a nothing spot above the chimneytops. Chalking on walls messages I did not understand. Tzaddik, he wrote. Sephirot, sefer, sippur. And with fingers straight out his eyes went back till they were white as his chalk and his puppethands trembling. And even then I thought of his son: Jacob. What would he do with his father a shame and his mother having to sew to earn enough? For the pitying rabbi handed Herschel only a few pittance of coins as a gift.

Jacob too with his prophecies, mad plans for the future. Father like son, as they say. Newspapers he reads now—the Tageblatt, stories of Coney Island. Dreams uncoming of the Promised Land. Always a hoper, Jacob is, the sweet fool. A child with back bent, hair curling gray at the ends. But when you look to the heights, hold on to your hat.

“These gears that I make in the jewelry store,” he said last week. “It is the same as the big rides there. I could build them too. New ones—The Crossover Track. The Firebird. A little money to start, that’s all that I need. I will talk to the men at the synagogue.”

I have heard all. “Why waste money on this? On your words no buildings can be built. We are getting old now. You have the watchstore. Enough. Sarah has moved to the Bronx. Judith to Flatbush. And yes our flat is better than most, no boarders no longer. But all our money you have ‘invested’ for your dreams, always gone and nothing back.” The American way. Streets paved with money. Money taken from us. Go out at night it is tight to the ground no way of grabbing it.

“Why do you not want the things I want?” he asked.

I pursed my lips and was silent. Jacob like Herschel and the rabbis watching for signs in the sky and not this room with its roaches or the birch trees in Volapzhin where the road to Kiev curved. Remembering nothing of the work I do, the washing and scrubbing of the clothes. Heavy with water, hanging like Herschel’s arms without shape, set to dry in the soot on the line. “With respect,” Jacob says. But I have no respect for he who does not match his socks. Who does not know that someone else must match his socks.

Left to me the world as it is. The present and the past. The real knowing.

But there was a time when with Jacob gladly happily I went into the deep woods or behind the grainrows, his fingers soft on my back studying my skin as if to draw to sculpt. But here in the New World nights I said yes but only to endure. And so I swelled like a mushroom in the moss and eyes on my middle not my face. Already losing, passing. A weight to keep me from my flying. But for Jacob it was everything. Nights he would sit and kiss my swelled skin and tell stories to it. “Listen, child,” he said. “You will be great. You will be beautiful. A house of your own. The world will be a dream that will come true. No monsters to fight. Growing straight and tall and strong.”

Already his eyes turning in love towards this not yet a thing inside of me. Singing in a low voice no words just songs made of sounds as he had never sung to me. Then after the sweating and screams in the back room here at East Broadway the midwife Shaina held it up. And I thought, another thing has been taken from me, my body. They said, it is a girl. Lea. And only then I knew it was not a girl I wanted, a girl who would grow to look too much like me. Beautiful as I was beautiful, but not the same. Eyes like the ghost of my eyes, lips like the trace of my lips. Her life like a road, and the sun and her stepping quickly away.

She cried all night for what? Milk—me. Like the story Leib told, the Dybbuk that came in the darkness and drained the soul from you. I was a calf only to be milked. A curse on me after America, another curse. A burden still, she who will return tonight to ask me again to take her back. As if I had not already let her go from the first. As if she had not demanded it.

But sometimes there was more. To her I would sing in my voice that was not one of beauty. A daughter of Zion rocking her to sleep. Cooing of snow white goats and raisins and almonds. The sweet life of the past. And once she wanted the circus and I remembered the circuses that came to Volapzhin in the fall. I kissed her on the head and said, “Yes, we will go, together.” On that day I changed into my red dress barely fitting anymore and taking her hand we walked through the streets and everything was beautiful. Lea pretty in her blue skirt and her face up to mine, mouth open as if to drink me in. Her hands copying, her eyes recording. When sometimes I do not want to remember or be remembered.

At the circus early we looked up at the red white and blue of the big top towering and smelled the gamy smell of the animals. In Lea’s open eyes the same joy mirrored upwards as mine. By the animal pens we waited to pet the horses that pressed long snouts to our faces. Air hot through their nostrils, hair tough on their backs soft at the mane. Lea scared at first but when I patted them and they licked my hands expecting something not there, “Mama, mama pick me up,” and I did. Wriggling in my hands she looked at the horse; the horse looked at her. Sad eyes demanding in the body of power. Mouth moving sideways to chew. Her hand out touching and laughing high she was light, light in my arms. I showed the elephants to her, trumpet trunks and white tusks flashing. “They are older than Grandpa Herschel,” I said. Behind my dress she hid looking out. “See, they are like maps.” Wrinkled with hills. Their eyes seeing back through the years. I had brought peanuts for Lea to toss to them, their trunkends rooting through the shells with gentleness, like the hands of a blindman on a face.

In our seats we waited for the organ to wheeze and blaze, our shoes sticking to the floor. For cotton candy Lea asked “Mama can I have some?” as the man moved past holding the pink clouds like sunsets on sticks. I called but already he was far too far but he will come again I said. You will get your candy. And the music started and first the clowns all in their many colors. Bright unlike the gray suits of everyone. Lea laughing at them acting so serious everything so much mattering but then always tripping falling water squirting. And in one tumble his red nose came off and stooping he picked it up and Lea’s hand reached for my dress. Her eyes alive watching without fear.

Then the ringmaster in his black coat, applause and taking off his hat. Red vest smooth and soft but the brown middle button barely held by the threads. Easy he stood knowing he was master, whip in his hand. Why should there be him, why not clowns and then animals but instead he pausing insisting we look at him in his cloak and his voice soft as if rubbing it across my arms? Not like the little circuses in Volapzhin, a family and a pony and a bear. The ringmaster father with gray hair, a rumpled jacket with dust on the shoulders. The child underfed older then me but no breasts yet balancing barely on a red ball, feet moving tip tip careful.

The horses galloped into the ring. “Look—look at the horses,” I said to Lea. “There is the one you touched. There—your friend.”

“Yes, yes,” she said, but cannot speak more. Trotting around they came, full big horses and the rider in a dress long and trailing, beautiful as wave edges, white foam from the ship’s back. But then it was happening again—a flash of black and crackle of wood on the edge of burning in Volapzhin. The horses swinging round, and the world gone dark in my eyes. Papa and the sliver of a swordblade descending. Blood on his chest. I was lost not seeing not hearing when the man passed again and Lea called “There, can I have my candy now?” Too late. Her eyes up on me pulling my hand hard till it hurt, like the anchor from the ship holding me down.

And now Lea not laughing but looking at me minute by minute. The animals the same as in Volapzhin but here suffering in sorrow. The horses beaten in the back, the dogs who do not jump through hoops as they should kicked and left to die. The dead following the circus train from town to town. And again I was fooled almost to joy. With the colors the noises of the crowd the animal blur pressing on me in pleasure but soon it is too much. It wants me to forget.

So when it was over with a sick feeling I did not try for Lea’s cottoncandy. On the way out almost crying “What about the candy, mama?”

“It is too late,” I said, not angry not wanting to hurt. “Next time.”

There it is again. The voice. Not from my dreams but here, real. A cry not for help but beyond help. Half sob but more than sob. Sounding like a voice I have heard before. Rising from the street outside. I rush to the window. The buildings are dark, the streetlights off for the night. Nothing; no one.

Still I hear it, fainter now. I wrap the shawl around my thickening shoulders, set my feet into my shoes, and unlatch the door. The hall is quiet, only the shuffle of Amira’s heavy feet next door. The floorboards creak like a man moaning in pain. Step by step I go down through the darkness, feeling with my hands the fetid walls. Waiting for the rustle of the rats, bristle of their fur against ankleskin.

But they too must be asleep. Light leaks through the glass of the streetdoor. Slowly I turn the lock. Through the walls Mrs. Teplitsky’s snores. Good.

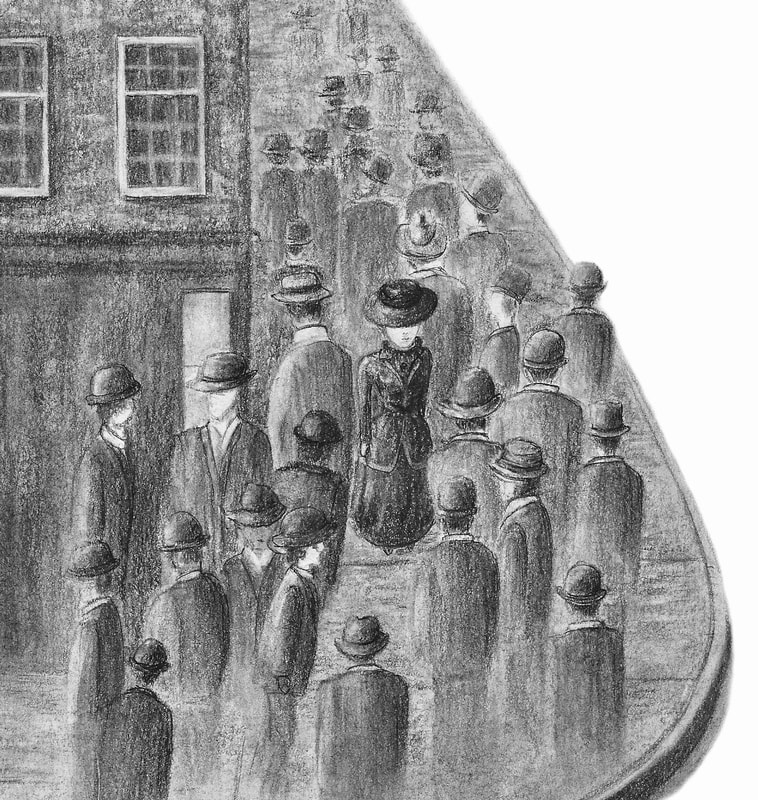

Moonlight filters down the stone steps. Silence. The voice gone. Along East Broadway the building fronts repeat. Brick and stone and brick and stone. Thousands like me, asleep, and only I to hear this call.

Even now the streets are not empty. A man trudges through the darkness: a baker, a grocer. Never is there a time when work is not to be done. Even in the darkest crevice of the night. No Sabbath in this world. No rest from the moneymaking.

There: movement. In the darkness of the doorway across the way. Shadows: one or two, writhing, struggling. A sound as of a cough. I step off the stairs and am halfway across the street. Will I beat them about the head? Let loose a cry for the police?

But I reach the curb of the opposite side and in the doorway there is no one. Not even a young couple hiding for a kiss. Empty.

Everywhere there is suffering that no one notices. That no one hears. Calls in the night unanswered. The walkers on the streets deaf to the sobs. Who pass and see nothing.

And this the world that Lea wants to join! Sewing flags and fucking with the goy. When she comes tonight she will trail that filth into this room, talking of the future that is nothing but a lie. “Freedom,” they say. Nothingword. Free. Free for these few blocks from Henry to Houston, in the Bronx from Mt. Eden to 176th. Our place to settle only. Pale. And the goy have everything. Money horses guns. And our rabbis cowards sighing saying nothing. Proclaiming that you must wait for the Promised Land that is a death. Speaking in Yiddish of the blessings of America: “We have come out of the land of bondeds” meaning bondage.

I wait one more minute for the cry to come again. But only silence. In shame I climb the stairs, a shade lighter now. Inside the room, the note from Lea still halffolded on the floor, a slight tremble in the cradlewood. A coo that is not of pleasant dreams but the outriders warning of tears oncoming. I look down at Avrom, left arm’s fat folds thrown across his face. His chin is trembling, his mouth half opened, eyes wrinkling beneath angry furrows of brow. I take him up in my arms, sit in my chair and look at my face that peers from the mirror—a bargain of Jacob’s, flecking and blistering with brown spots like the skin of the old woman I am not quite yet. Through the shadows I trace my wrinkles. Like mama in Volapzhin adjusting her scarf, roses and green stems. Mornings at the mirror, she wound it as I watched. Tucked by her chin, red like a scar. “Minna,” she said, “You see it is beautiful. Colonel Kovalenko purchased it for me. A man in Kiev. A man who loved me. It is important to wear beautiful things. When I pass even the cows should think, there is a woman.”

Mama was tall. Straight she sat in her chair. Her lip a line straight across her face. Her hair in grainwisps along the white fields of her cheeks. And then she bent and a sound came from her mouth, a cough of a Dybbuk deep inside. My hair wet and her eyes like stars falling coming apart but only tears. “Minna,” she said, “There is no other world.”

I crawled into her lap. A boat, I thought, the folds of her dress. I had not seen a boat, only pictures in a book that papa kept. We sailed together, mama and I. A river of roses. The scarf steeped with her tears. The boat of her dress rocking as her breath stormed, like when I stepped aboard the ship to America, from Hamburg after the harrowing from Kiev west. Wood it was, only wood, to hold back the sea, and this to be my home for the days till land. Dead and yet still moving as if alive when the storms roared. But after the week of blue blank, green humps on the world’s edge. Rayna on the deck pressed her mouth to her boy’s cheek, throwing her left arm up free as she cheered. I too caught in the hopewebs. First only wedges of color, hazed, then trees and grass, and then we were between two green cliffs and the bay before us. White sails. Birds glimmering on the waterskin. And shouts around me, secret voices from lips long silent. With others pressed, body, mind, voice. I took Jacob’s hand. Quiet, eyes not yet believing. His face wet from spray. No, tears. Across the glare Manhattan, he said, woodspires of ships and docks.

But in the gleam suddenly the statue. Red firetip above the bronze going green. Jacob removing his hat, smiling through his beard. Miles and weeks on the water, here to be free, and no welcome but this they give, a statue? A giant too big to crush us, guarding the harborside. A queen, Tsarina with her crown, and America, Jacob said, a land with no Tsars. Already they bow, these fools gathered around me on the boatdeck. Always they are forgetting. Beat me, beat me! they cry. Ready to be serfs and servants again. Slaves to this new land as slaves to the old. “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breath free,” I know now. Give me. And what is to be given to us in return?

So I should not have been surprised. Only one month after the voyageend, when the streets of this world were new, when we had nothing but our hunger, Rabbi Pelsner called me to his basement room at Eldridge and Canal. The doorway so low I had to duck to get inside. The rabbi nodding his head and squinting up his eyes as if this would convince me that he was a man of wisdom. Across the rightmost corner of his desk an overflow of dried white wax like a river frozen in its plunge in the wintertime. “You see,” he said, “it is hard for the Jews in this new country. So many there are that do not want us. We must be careful so that they see the best of us. So you, a married woman with a husband, should not be walking the streets in these clothes that are not for outside wearing. Even if you are not a one to shave off your hair as the Lord says, at least to cover it. To wear dresses that reach below your ankles.” His eyes that were heavy dropped to the bottoms of my legs.

So from the rabbi’s room I went into the street and around me no one that I knew but only strangers and the world unlooking. What a greeting for this land! Wanting us all the same—gray in our sack cloths and my face fading with age like night coming on. Left inside like a shell forgotten. And then it was that I cried though I will not cry again.

I said, I will see this world. Despite all. Despite the rabbis and the henwomen, cowslow and grazing in gossip one to another. Sticking close when there was a world to be mapped. Each street to wander, block after block. To know this city that was forced on me.

So I walked, walked and looked. At the peddlers the same as in Volapzhin pushing westward along Grand, knifesscrapers crying harsh with voices ground like their knives. I followed them, hearing the pleas from the pushcarts selling rags and dirty fruit. Crates of eggs or candles for the home. Children tottering past, tossing pebbles and ground glass, whistling of cops. In the alleys playing with an old box and barrel, their mothers where? As we in Volapzhin, but the dirt there had been clean.

Everywhere as I walked the people were crowded close: cardplaying on stoops, laying the washing from high windows. Five floor buildings tightpacked, elbowing for room, metal cages running in Zs down the fronts. In storefronts on Clinton St. the barely more than minyan synagogues, chairs and a torah in the empty space. Ceilings of pressed tin in patterns. Landsmanschafts, so that each block each building was a spot on the map of the old world. Twenty minutes across Europe. Above Houston from B to the River, the Hungarians. Galicians between Houston and Broome, east of Clinton. Romanians west to Allen. And then for us from Grand Street south.

Into the windows of the stores past Essex I looked at the things that there were in America. The market shops like Solomon Gold’s or Haracz and Sons with flat on their gravebeds of ice the schools of smoked fish—dull gray-brown herring and jewel bright salmon. More here than I had eaten in my entire life in Volapzhin. The floor soft with sawdust. The clerks bustling in crisp aprons. Outside the fatman barrels—sour and half-sour. Bursting in garlic juice with the teethbite. Tart on my tongue and turning my lips to white. Fritz the storeman reaching down to scoop the thickest out for me in my red dress. When I was my most beautiful then.

Past the buildings with their windows shut where the women my age but no husbands would go to sew in the stifling heat. Returning late in the darkness with squinting eyes from threading needles and shoulders hunched further down each day. Molegirls who could choose only to live unmarried and then die.

I walked that day across Chrystie Street and down Bowery to Park Row to see for the first time the center of this world. The room at the maze heart, engines humming, shadowed even in the morning sun. The buildings so high that I could not breathe for fear of them falling. Up into the air when in Volapzhin the houses crept in rows along the ground. I thought, God will come to smite these men with their Babel towers. But when I looked up I could not help but laugh. For the buildings were not straight and serious like Rabbi Pelsner or Rabbi Meltzer, saying to the world you must see that I am a powerful man. Fifteen stories or more, but they played and joked like children. The red brick Tribune building striped with white stone like a package tied with ribbon. At the top off-center a spire pointing up. Taunting that it was so high. A boy waving proud from a treetop he had climbed.

I stood on the streetcorner, red in my dress. Hungry they watched me, the men from the stocks in their tight suits and hats all the same. Dead in their eyes in their pale faces. They looked. Jewess they knew perhaps but still beautiful. I looked at their looking. Feeling the heat in me, flushfull. Bird air lightness. I was more. Not Jacob’s. Free. Back in the old woods, alone. Calico damp in summersweat on my legs, stockings soaked. For in their minds I could go with them past the signs saying “No Jews” or the nosigns meaning the same into their houses with thick carpets and carved darkwood. To see the uncut books on their shelves, the heavy couches with woodbacks curved like shipfronts.

But then he with the black hat came up to me, married I could tell. His wordbuzz of English I did not yet understand and I smiling with my lips but nothing more. His face was dark and secret, hand taking my hand even when he knew I did not know his words. Close up he was old, pinchnosed, secret with sins and teeth like a field trampled by beasts. Hot breath stinking, rawwound mouth. And with his pocketpen I stabbed him or wanted to stab and watch his face bleed leaning in staggering paling and then all the men the same in their hats falling dead in America pen to their hearts. Blood in my hair on my dress red.

These were the men who ran the world. I watched, eyes open. Was this the Golden Land that Jacob brought me to? How is it better, different than Volapzhin? Only what has been lost. Stale air now and no trees. Noise and noise and the clocks ticking. Grayness falling on me in sleep. Or worse: the girls pressing to the windowedge; blueorange spark of flames bursting from behind. As it was in Volapzhin with the horsemen and papa. Death scattered everywhere like salt from a shaker.

I ran like a streak of light from City Hall back up East Broadway to collapse on a bench in Seward Park. So this was the world. This was to be my life. I watched the chessmen playing their games. Stooping suspendered to move sideways their black white knights. With Lea I listened to the speakers thundering of injustice to the scruffy crowds ignoring them. Beneath the brick stiff spine of the Library, towering in newness.

But how my memories muddle! The present presses. The years that came after nosing their way into the times before. No Lea of course in the first days of my walks. But no Seward Park either for there to be a library. Blocks of buildings not yet torn down, and the books in the basement rooms of the old Aguilar Library still smelling of mold and dust. No speakers in the Park, or if there was a Clara Lemlich then I did not know I did not know her.

Why do I have to think always of Lea? Of our days together, and what pleasures there might have been? I want to return to the years before unstained. To the New York when first I saw it. When I wandered the streets fresh without name, the voices without sense. Each strip of paper peeled back to the past, one atop another. Shops that have changed and fled, houses rising and falling. To get beneath the dirt of life and years built up. But I cannot forget what has come since. The nowness seeps back like roots going downward from air to earth, and brings no flowers. Smudging out the maps of what was.

But even then, at the first moment, when we stepped from Castle Garden, before the rabbi and Lea, it was too late. Always it is too late. For it is not this New World that I dream of. When in dreams I walk the lightstrip going forth, in terror it comes round circling. Taking me back only to where I was, tracing the wandering paths through Volapzhin, the shadows of the forest falling close. Even when I do not want to think of Volapzhin. Here the brick house of the Dubinsky’s and there the post where they tied their dog where the rabbi used to stop on his walk home to talk over the Talmud with Berl the father. There the house where Basia lived where in the yard we would play Cossacks and throw each other down in the dirt and mud. And there the tree where Jacob and I met for the first time with heads up to look at the branches, golden curls and the turn of his gaze smiling. But then at the bend where the river nuzzles close to the road rightward a gray wall of fog of forgetting. Inside somewhere the slaughterhouse I know is there but the size and color gone. Wood or stone? Pigs or cows or what? No more the stifled grunts, terror of eyes I must have heard or seen. All faded as in the spring the mist would rise off the river and only the housetops clear. Blotted, blurred, and who knows what beyond.

I stand at the edge of the water and look back at what is drowned and drowning. I want to see again, to remember. Not just Lea, her remnants and reminders. But Volapzhin: as in my New World walks at every streetbend the town comes to me in pieces. Sunset reflections from the synagogue in the glint in the glass of a storefront. The waste of cloth in the streetgutter, bright as in the top drawer of mama’s dresser. From scraps I could sew, if I could sew in light, and the Old World would return. Stitch after stitch into coat or cloak. Market streets on the arms and the smell of horses at the hems. In fabric shimmering of many colors and patterns and shapes. Around my shoulders I place it, soft on my skin, and again I am at home in anywhere, walking the streets as they were. But like water it slips from my back, sinking into the earth, and my eyes open only to New York and the dawn.

Eyes closed. The lightspecks of dreamsleep still flashing in the darkness. What is it, the word? To my mudheavy tongue it does not come. In a language that is not mine. Glivorem: Fireflies. Yes. The rain or earth or what lit them blew them to birth. From the grass and grain and the cool stream rising, back in Volapzhin where the road to Kiev curved. In the oncoming nights, when I was beautiful. Floating in fullness past the foolboys watching.

Thirty-five years or more ago. Before the journey to this America, the deaths and might-as-well-be deaths. Such a span of time and yet still I remember. The waterlight coming clean over the roofs at dayend. To wash the roads like rain. The sun thronesitting at the streamedge, winking Godeye picking out in light the high tree leaves. You, you, I choose, not you. In the mudstreets the broken pots and chicken blood turned to gold dust and our house to polished brass, warm flameedge orange. Light burning blinding and my eyes from the synagogue the shops dazzled away. Our faces glowing beautiful, mama’s and papa’s and mine.

Misha with his rough tongue begging for scraps and the streetdogs feeling in their fur the dusk coming. Shh, the day said, like mama in her moods, shhh!, and the noises hushed. The light still strong in the high clouds but down here darkening quick to night. The world sent like a child early to bed and the parents in the daysky talking loud. And then the sun dropped down and the pink clouds faded, in the east still tipped with orange but blackening quickly west to darker deep blue winter blue. The knit of light loosening, and the stores and houses, the Dubinsky’s and the Abramson’s and the Pevzner’s, dissolving to dull grey brown. Wood boards blending and the deep ruts smoothed.

Streethouses pressed flat like flowers in mama’s book, dark rectangles and squares and then fading. Screen after screen of night dropping, blotting like Herschel’s ink. Gone the synagogue at the roadbend, grainfields distant, weeds on the streetedge. All cleaned in the pure darkness.

The black nightwall close now; only the porch left behind in the grayness. And then as if breathed up from groundfire the fireflies would rise. Mama said watch and I watched close and they winked at me and I waited again for them to wink Wink! but each time different and I did not know where they would come again or when. Before only darkness and papa’s snores but now in pinholes of light I could see the roadmud and the house across the way where Basia lived. The trees there once more for a moment in the green circles and the grass green in pieces. For hours they danced, the fireflies, rising and falling in and out like breath but no pattern.

But eyes open. Into black oceanwater Volapzhin sinks, up over housetops and spires and gone. The fireflies quenched in the darkness, green lidblots dissolving. Of a beautiful dream there is no use, if the dawn in the room is cold. Clay pots on the dustshelves, dull rugpatterns twined. A gasp of breath: mine. Jacob beside me with his snores. The whereplace returning. New York, New World. 5673. 1913. The 21st of May. Oil lamps shining warm gold, but no fireflies.

It is too much of a muchness, too soon in the morning. A rumble deep in my head. Hoofbeats? Fistgrasp at my breath. The burnflush rising. But it is only little Avrom, mouth open stirring in the cradle. The street outside is calm, buildings unburnt. No high whinny of horses, crack of hoof on wood before the splintering. I rise from the bed, feel the rough ridges of the planks against my footsoles. My eyes can see in the darkness: the stove, the cradle. In Avrom’s ear I whisper soft in English. His legs fat like his father’s kicking against the night. He will know more than me, more than Lea, new language and old stories too. But English is hard, a glove that does not fit. Always another finger outsticking, no cloth to cover. And dreams the hardest; at night the books the signs in Volapzhin still in Yiddish or in Kiev “ні євреї.”

Still three hours till the dawn, but a change in the thickness of darkness. Enough to see the patterns of the wallpaper, the wood table with faded brown cloth, marked by the old lines of Lea’s school ink.

A flash of white on the pocked woodfloor. Reflecting for a moment the moonlight. A square of paper, half-tucked beneath the apartment door. It has been slid there, in the night. I stoop to look. Left top corner crumpled, greyed by dust. It is a knife: to cut my breast with its edges. Telling me I am not safe. Notes can be slipped in secret to me: threats. Robbers can scale the buildingsides and pry back the windowframes. This room is nothing. I press my hand to the door. Strong and solid it seems, but it is like the curtain walls at the theaters, letting through light and anything. Who else will come with their words to wound me?

But it is from Lea. I know already. I unfold the creases of the paper. Scrawled inside is her child writing: the looping g’s and unsteady d’s. I am coming to see you tonight. It will be good for us to talk.

I am the you she is coming to see. Not Jacob, still asleep. Did she drop the letter off with Mrs. Teplitsky? Or in the silent hours of night creep up the stairs to place it here herself? I press myself to my feet, my knees aching. Always now I can feel my bones and body that before were light and nothing.

I watch Jacob, his chest swelling like sea waves before the break, swaddled in the red and purple coverlet. He knows of this. They have met in secret. Planned it all. Conspiring against me.

America has made them weak. Lea has learnt nothing. At her age I had lived two lives for her one. Soaring I had come in birdflight across miles and countries, plains of Kiev to the valleys of Wall Street. A continent and an ocean. In horse-cart and steerage. She does not know hunger, like I know. She does not know the struggles and the sufferings, or the happinesses that were. And so she did not listen. Meeting with the nogood men after the sweatshop sewing that I had not wanted for her to do. Already I had begun to suspect: that little fatness around her middle. “What have you been eating?” I asked. “The look of you—it is a power you should not lose.”

It was over dinner; cabbage and kasha. “I am pregnant,” she blurted, her elbow striking the tableside hard.

Jacob blinking as if it waved the fact away. “What?” he cried. “You are to be married?” The innocent.

She pouted, face red and angry behind the tears. “He has run off.”

“The swine!” Jacob cried.

“And you did this with him?” I asked. “One of these American shysters you love so much? On about his money and his plans, ‘you are more beautiful than the Gentile girls’?”

“No, mama. It was not like that. He was …”

“I do not want to hear of this filth. You are a shanda.”

“Minna…” Jacob’s hand on my shoulder, trying to stop my feelings, as he always does.

Lea’s face was blank. Dead.

“Go, go,” I said. “I am used to this. You will leave me anyway. It may as well be now.”

The fire was bright in my eyes and my breath short. But the words were not quite right to say what I wanted.

“I don’t understand,” Jacob said to me, his face open in appeal. “She is not asking to leave.”

But she had thrown away what we have given her. For Jacob in Volapzhin said, “we want a better place for our children. We must go to the New World.” So: the town gone and mama and the horse heaving its dying sighs and Jacob choking down his shame. For what? Her future now is only shame and the squalidness of the sweatshoppers we had almost worked ourselves free of. And if so then why have we endured the horrors of this world and the passage here?

“I don’t know what you want of me,” Lea whispered. “I don’t know what you want.” Like an old woman she stood from the table, unsteady.

I want this world to be Volapzhin. I want Lea to be a success but not in the ways of this America. I want the time then to be the time now. These things that are not possible.

“Out of my house, whore,” I cried. Unfaithful to my care for her.

She swayed like a tree beaten by the wind. “What? Where will I live?” She looked at me with the face of a child forced to see sights too much for her. A face I know well. And then as if shocked from the subway rails she bolted down the stairs. A silence as of breath being held and Jacob running after her, coming back with eyes like holes waiting to be filled. But he is a coward and went along.

So then a return eight months later and her bastard child forced on me. She will not stay again beneath this roof, but for Avrom who cries in the night I have relented. Now I am stuck to go through it again with this lump of flesh that wants and wants when it was done and over.

Still Jacob does not accept. Asking yesterday again, “Why is it that you will not welcome her?” He is always asking why. Wanting to talk and wonder. “It is not her getting together with the boy, is it?” he said. “Because we did too before the wedding, you remember. So, she is unlucky with the child. She has paid, she is sorry. A mitzveh it is, to be blessed with a family. It is too much for you at your age to care for a newborn.”

“What age is that?”

“We too can be blessed.” Ignoring as always.

“She is no longer my daughter,” I said.

He shrugged his hands up, breath out hot. “Why? Why this still? It is two months now that we have had Avrom, eleven months without Lea, the fruit of our souls. Is not that too long? We must take her back.”

But I sat silent. While our love was strong we lay on the edge of a sword, now a couch sixty yards wide is too narrow for us. He with his talking, over and over again, plowing the land that has been plowed. Talk is worth a dollar; silence is worth two. For why should I say or know why I feel? The same with the sadnesses that creep on me. I could say, “It is the days with nothing to do, only to sew, no books to read,” but now with teaching there is something in the days and I have the library to visit for the books. And still the sadnesses. Jacob before would sit beside me and ask, “What is wrong, my kinigl?” but I had no want to talk or to explain. It is as if they require happiness of us. To sing of this land, this America. This America that takes my daughter and my past. She eats the seeds of the fruit of this world until she is ruined for anywhere but here. Distracted by the clothes on the mannequins in the store windows and not seeing the blankness of their faces and their hands cut off.

I tell a story that no one in this New World wants for me to tell. For how can we sing songs in a world that is strange? To my mouth’s roof my tongue cleaves.

I let the letter drop to the floor. Trash for the trash she is. Words echo in my head. From the street, or in the room itself. Breath shorter in my chest. But the sounds are from the backroom only. A mumbling. I push open the door. Herschel who never sleeps sits at his desk writing. The “holy” one. Mocking me with his pages filled with squares and circles. In-law, father-in-law, bound to me by rules and power. Making words into numbers. Letters mixed with letters, picked out from the holy books. Secrets from God’s tongue only for him. Herschel whose lap as an infant Lea crawled into as if it were a better home than mine. Ignoring the urine and the crumbs.

His tongue clicks in his mouth as I stand over him. His pants are off again; his cuffs that I must wash stained with ink. The ageless legs veined blue but still strong. “Herschel, you must sleep,” I whisper, but his hands move on unchanged. All this for nonsense, and his mouth always hungry to be fed. Herschel who people called the wise but who when I was a child in Volapzhin was only a strange one to be avoided. “He is thinking deep thoughts. Thoughts of God. Not for us,” Papa said.

But why I thought should God not speak in our language but in words that made no sense? For all day through the town Herschel in his long black coat looked up at the sky or a nothing spot above the chimneytops. Chalking on walls messages I did not understand. Tzaddik, he wrote. Sephirot, sefer, sippur. And with fingers straight out his eyes went back till they were white as his chalk and his puppethands trembling. And even then I thought of his son: Jacob. What would he do with his father a shame and his mother having to sew to earn enough? For the pitying rabbi handed Herschel only a few pittance of coins as a gift.

Jacob too with his prophecies, mad plans for the future. Father like son, as they say. Newspapers he reads now—the Tageblatt, stories of Coney Island. Dreams uncoming of the Promised Land. Always a hoper, Jacob is, the sweet fool. A child with back bent, hair curling gray at the ends. But when you look to the heights, hold on to your hat.

“These gears that I make in the jewelry store,” he said last week. “It is the same as the big rides there. I could build them too. New ones—The Crossover Track. The Firebird. A little money to start, that’s all that I need. I will talk to the men at the synagogue.”

I have heard all. “Why waste money on this? On your words no buildings can be built. We are getting old now. You have the watchstore. Enough. Sarah has moved to the Bronx. Judith to Flatbush. And yes our flat is better than most, no boarders no longer. But all our money you have ‘invested’ for your dreams, always gone and nothing back.” The American way. Streets paved with money. Money taken from us. Go out at night it is tight to the ground no way of grabbing it.

“Why do you not want the things I want?” he asked.

I pursed my lips and was silent. Jacob like Herschel and the rabbis watching for signs in the sky and not this room with its roaches or the birch trees in Volapzhin where the road to Kiev curved. Remembering nothing of the work I do, the washing and scrubbing of the clothes. Heavy with water, hanging like Herschel’s arms without shape, set to dry in the soot on the line. “With respect,” Jacob says. But I have no respect for he who does not match his socks. Who does not know that someone else must match his socks.

Left to me the world as it is. The present and the past. The real knowing.

But there was a time when with Jacob gladly happily I went into the deep woods or behind the grainrows, his fingers soft on my back studying my skin as if to draw to sculpt. But here in the New World nights I said yes but only to endure. And so I swelled like a mushroom in the moss and eyes on my middle not my face. Already losing, passing. A weight to keep me from my flying. But for Jacob it was everything. Nights he would sit and kiss my swelled skin and tell stories to it. “Listen, child,” he said. “You will be great. You will be beautiful. A house of your own. The world will be a dream that will come true. No monsters to fight. Growing straight and tall and strong.”

Already his eyes turning in love towards this not yet a thing inside of me. Singing in a low voice no words just songs made of sounds as he had never sung to me. Then after the sweating and screams in the back room here at East Broadway the midwife Shaina held it up. And I thought, another thing has been taken from me, my body. They said, it is a girl. Lea. And only then I knew it was not a girl I wanted, a girl who would grow to look too much like me. Beautiful as I was beautiful, but not the same. Eyes like the ghost of my eyes, lips like the trace of my lips. Her life like a road, and the sun and her stepping quickly away.

She cried all night for what? Milk—me. Like the story Leib told, the Dybbuk that came in the darkness and drained the soul from you. I was a calf only to be milked. A curse on me after America, another curse. A burden still, she who will return tonight to ask me again to take her back. As if I had not already let her go from the first. As if she had not demanded it.

But sometimes there was more. To her I would sing in my voice that was not one of beauty. A daughter of Zion rocking her to sleep. Cooing of snow white goats and raisins and almonds. The sweet life of the past. And once she wanted the circus and I remembered the circuses that came to Volapzhin in the fall. I kissed her on the head and said, “Yes, we will go, together.” On that day I changed into my red dress barely fitting anymore and taking her hand we walked through the streets and everything was beautiful. Lea pretty in her blue skirt and her face up to mine, mouth open as if to drink me in. Her hands copying, her eyes recording. When sometimes I do not want to remember or be remembered.

At the circus early we looked up at the red white and blue of the big top towering and smelled the gamy smell of the animals. In Lea’s open eyes the same joy mirrored upwards as mine. By the animal pens we waited to pet the horses that pressed long snouts to our faces. Air hot through their nostrils, hair tough on their backs soft at the mane. Lea scared at first but when I patted them and they licked my hands expecting something not there, “Mama, mama pick me up,” and I did. Wriggling in my hands she looked at the horse; the horse looked at her. Sad eyes demanding in the body of power. Mouth moving sideways to chew. Her hand out touching and laughing high she was light, light in my arms. I showed the elephants to her, trumpet trunks and white tusks flashing. “They are older than Grandpa Herschel,” I said. Behind my dress she hid looking out. “See, they are like maps.” Wrinkled with hills. Their eyes seeing back through the years. I had brought peanuts for Lea to toss to them, their trunkends rooting through the shells with gentleness, like the hands of a blindman on a face.

In our seats we waited for the organ to wheeze and blaze, our shoes sticking to the floor. For cotton candy Lea asked “Mama can I have some?” as the man moved past holding the pink clouds like sunsets on sticks. I called but already he was far too far but he will come again I said. You will get your candy. And the music started and first the clowns all in their many colors. Bright unlike the gray suits of everyone. Lea laughing at them acting so serious everything so much mattering but then always tripping falling water squirting. And in one tumble his red nose came off and stooping he picked it up and Lea’s hand reached for my dress. Her eyes alive watching without fear.

Then the ringmaster in his black coat, applause and taking off his hat. Red vest smooth and soft but the brown middle button barely held by the threads. Easy he stood knowing he was master, whip in his hand. Why should there be him, why not clowns and then animals but instead he pausing insisting we look at him in his cloak and his voice soft as if rubbing it across my arms? Not like the little circuses in Volapzhin, a family and a pony and a bear. The ringmaster father with gray hair, a rumpled jacket with dust on the shoulders. The child underfed older then me but no breasts yet balancing barely on a red ball, feet moving tip tip careful.

The horses galloped into the ring. “Look—look at the horses,” I said to Lea. “There is the one you touched. There—your friend.”

“Yes, yes,” she said, but cannot speak more. Trotting around they came, full big horses and the rider in a dress long and trailing, beautiful as wave edges, white foam from the ship’s back. But then it was happening again—a flash of black and crackle of wood on the edge of burning in Volapzhin. The horses swinging round, and the world gone dark in my eyes. Papa and the sliver of a swordblade descending. Blood on his chest. I was lost not seeing not hearing when the man passed again and Lea called “There, can I have my candy now?” Too late. Her eyes up on me pulling my hand hard till it hurt, like the anchor from the ship holding me down.

And now Lea not laughing but looking at me minute by minute. The animals the same as in Volapzhin but here suffering in sorrow. The horses beaten in the back, the dogs who do not jump through hoops as they should kicked and left to die. The dead following the circus train from town to town. And again I was fooled almost to joy. With the colors the noises of the crowd the animal blur pressing on me in pleasure but soon it is too much. It wants me to forget.

So when it was over with a sick feeling I did not try for Lea’s cottoncandy. On the way out almost crying “What about the candy, mama?”

“It is too late,” I said, not angry not wanting to hurt. “Next time.”

There it is again. The voice. Not from my dreams but here, real. A cry not for help but beyond help. Half sob but more than sob. Sounding like a voice I have heard before. Rising from the street outside. I rush to the window. The buildings are dark, the streetlights off for the night. Nothing; no one.

Still I hear it, fainter now. I wrap the shawl around my thickening shoulders, set my feet into my shoes, and unlatch the door. The hall is quiet, only the shuffle of Amira’s heavy feet next door. The floorboards creak like a man moaning in pain. Step by step I go down through the darkness, feeling with my hands the fetid walls. Waiting for the rustle of the rats, bristle of their fur against ankleskin.

But they too must be asleep. Light leaks through the glass of the streetdoor. Slowly I turn the lock. Through the walls Mrs. Teplitsky’s snores. Good.

Moonlight filters down the stone steps. Silence. The voice gone. Along East Broadway the building fronts repeat. Brick and stone and brick and stone. Thousands like me, asleep, and only I to hear this call.

Even now the streets are not empty. A man trudges through the darkness: a baker, a grocer. Never is there a time when work is not to be done. Even in the darkest crevice of the night. No Sabbath in this world. No rest from the moneymaking.

There: movement. In the darkness of the doorway across the way. Shadows: one or two, writhing, struggling. A sound as of a cough. I step off the stairs and am halfway across the street. Will I beat them about the head? Let loose a cry for the police?

But I reach the curb of the opposite side and in the doorway there is no one. Not even a young couple hiding for a kiss. Empty.

Everywhere there is suffering that no one notices. That no one hears. Calls in the night unanswered. The walkers on the streets deaf to the sobs. Who pass and see nothing.

And this the world that Lea wants to join! Sewing flags and fucking with the goy. When she comes tonight she will trail that filth into this room, talking of the future that is nothing but a lie. “Freedom,” they say. Nothingword. Free. Free for these few blocks from Henry to Houston, in the Bronx from Mt. Eden to 176th. Our place to settle only. Pale. And the goy have everything. Money horses guns. And our rabbis cowards sighing saying nothing. Proclaiming that you must wait for the Promised Land that is a death. Speaking in Yiddish of the blessings of America: “We have come out of the land of bondeds” meaning bondage.

I wait one more minute for the cry to come again. But only silence. In shame I climb the stairs, a shade lighter now. Inside the room, the note from Lea still halffolded on the floor, a slight tremble in the cradlewood. A coo that is not of pleasant dreams but the outriders warning of tears oncoming. I look down at Avrom, left arm’s fat folds thrown across his face. His chin is trembling, his mouth half opened, eyes wrinkling beneath angry furrows of brow. I take him up in my arms, sit in my chair and look at my face that peers from the mirror—a bargain of Jacob’s, flecking and blistering with brown spots like the skin of the old woman I am not quite yet. Through the shadows I trace my wrinkles. Like mama in Volapzhin adjusting her scarf, roses and green stems. Mornings at the mirror, she wound it as I watched. Tucked by her chin, red like a scar. “Minna,” she said, “You see it is beautiful. Colonel Kovalenko purchased it for me. A man in Kiev. A man who loved me. It is important to wear beautiful things. When I pass even the cows should think, there is a woman.”

Mama was tall. Straight she sat in her chair. Her lip a line straight across her face. Her hair in grainwisps along the white fields of her cheeks. And then she bent and a sound came from her mouth, a cough of a Dybbuk deep inside. My hair wet and her eyes like stars falling coming apart but only tears. “Minna,” she said, “There is no other world.”

I crawled into her lap. A boat, I thought, the folds of her dress. I had not seen a boat, only pictures in a book that papa kept. We sailed together, mama and I. A river of roses. The scarf steeped with her tears. The boat of her dress rocking as her breath stormed, like when I stepped aboard the ship to America, from Hamburg after the harrowing from Kiev west. Wood it was, only wood, to hold back the sea, and this to be my home for the days till land. Dead and yet still moving as if alive when the storms roared. But after the week of blue blank, green humps on the world’s edge. Rayna on the deck pressed her mouth to her boy’s cheek, throwing her left arm up free as she cheered. I too caught in the hopewebs. First only wedges of color, hazed, then trees and grass, and then we were between two green cliffs and the bay before us. White sails. Birds glimmering on the waterskin. And shouts around me, secret voices from lips long silent. With others pressed, body, mind, voice. I took Jacob’s hand. Quiet, eyes not yet believing. His face wet from spray. No, tears. Across the glare Manhattan, he said, woodspires of ships and docks.

But in the gleam suddenly the statue. Red firetip above the bronze going green. Jacob removing his hat, smiling through his beard. Miles and weeks on the water, here to be free, and no welcome but this they give, a statue? A giant too big to crush us, guarding the harborside. A queen, Tsarina with her crown, and America, Jacob said, a land with no Tsars. Already they bow, these fools gathered around me on the boatdeck. Always they are forgetting. Beat me, beat me! they cry. Ready to be serfs and servants again. Slaves to this new land as slaves to the old. “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breath free,” I know now. Give me. And what is to be given to us in return?

So I should not have been surprised. Only one month after the voyageend, when the streets of this world were new, when we had nothing but our hunger, Rabbi Pelsner called me to his basement room at Eldridge and Canal. The doorway so low I had to duck to get inside. The rabbi nodding his head and squinting up his eyes as if this would convince me that he was a man of wisdom. Across the rightmost corner of his desk an overflow of dried white wax like a river frozen in its plunge in the wintertime. “You see,” he said, “it is hard for the Jews in this new country. So many there are that do not want us. We must be careful so that they see the best of us. So you, a married woman with a husband, should not be walking the streets in these clothes that are not for outside wearing. Even if you are not a one to shave off your hair as the Lord says, at least to cover it. To wear dresses that reach below your ankles.” His eyes that were heavy dropped to the bottoms of my legs.

So from the rabbi’s room I went into the street and around me no one that I knew but only strangers and the world unlooking. What a greeting for this land! Wanting us all the same—gray in our sack cloths and my face fading with age like night coming on. Left inside like a shell forgotten. And then it was that I cried though I will not cry again.

I said, I will see this world. Despite all. Despite the rabbis and the henwomen, cowslow and grazing in gossip one to another. Sticking close when there was a world to be mapped. Each street to wander, block after block. To know this city that was forced on me.

So I walked, walked and looked. At the peddlers the same as in Volapzhin pushing westward along Grand, knifesscrapers crying harsh with voices ground like their knives. I followed them, hearing the pleas from the pushcarts selling rags and dirty fruit. Crates of eggs or candles for the home. Children tottering past, tossing pebbles and ground glass, whistling of cops. In the alleys playing with an old box and barrel, their mothers where? As we in Volapzhin, but the dirt there had been clean.

Everywhere as I walked the people were crowded close: cardplaying on stoops, laying the washing from high windows. Five floor buildings tightpacked, elbowing for room, metal cages running in Zs down the fronts. In storefronts on Clinton St. the barely more than minyan synagogues, chairs and a torah in the empty space. Ceilings of pressed tin in patterns. Landsmanschafts, so that each block each building was a spot on the map of the old world. Twenty minutes across Europe. Above Houston from B to the River, the Hungarians. Galicians between Houston and Broome, east of Clinton. Romanians west to Allen. And then for us from Grand Street south.

Into the windows of the stores past Essex I looked at the things that there were in America. The market shops like Solomon Gold’s or Haracz and Sons with flat on their gravebeds of ice the schools of smoked fish—dull gray-brown herring and jewel bright salmon. More here than I had eaten in my entire life in Volapzhin. The floor soft with sawdust. The clerks bustling in crisp aprons. Outside the fatman barrels—sour and half-sour. Bursting in garlic juice with the teethbite. Tart on my tongue and turning my lips to white. Fritz the storeman reaching down to scoop the thickest out for me in my red dress. When I was my most beautiful then.

Past the buildings with their windows shut where the women my age but no husbands would go to sew in the stifling heat. Returning late in the darkness with squinting eyes from threading needles and shoulders hunched further down each day. Molegirls who could choose only to live unmarried and then die.

I walked that day across Chrystie Street and down Bowery to Park Row to see for the first time the center of this world. The room at the maze heart, engines humming, shadowed even in the morning sun. The buildings so high that I could not breathe for fear of them falling. Up into the air when in Volapzhin the houses crept in rows along the ground. I thought, God will come to smite these men with their Babel towers. But when I looked up I could not help but laugh. For the buildings were not straight and serious like Rabbi Pelsner or Rabbi Meltzer, saying to the world you must see that I am a powerful man. Fifteen stories or more, but they played and joked like children. The red brick Tribune building striped with white stone like a package tied with ribbon. At the top off-center a spire pointing up. Taunting that it was so high. A boy waving proud from a treetop he had climbed.

I stood on the streetcorner, red in my dress. Hungry they watched me, the men from the stocks in their tight suits and hats all the same. Dead in their eyes in their pale faces. They looked. Jewess they knew perhaps but still beautiful. I looked at their looking. Feeling the heat in me, flushfull. Bird air lightness. I was more. Not Jacob’s. Free. Back in the old woods, alone. Calico damp in summersweat on my legs, stockings soaked. For in their minds I could go with them past the signs saying “No Jews” or the nosigns meaning the same into their houses with thick carpets and carved darkwood. To see the uncut books on their shelves, the heavy couches with woodbacks curved like shipfronts.

But then he with the black hat came up to me, married I could tell. His wordbuzz of English I did not yet understand and I smiling with my lips but nothing more. His face was dark and secret, hand taking my hand even when he knew I did not know his words. Close up he was old, pinchnosed, secret with sins and teeth like a field trampled by beasts. Hot breath stinking, rawwound mouth. And with his pocketpen I stabbed him or wanted to stab and watch his face bleed leaning in staggering paling and then all the men the same in their hats falling dead in America pen to their hearts. Blood in my hair on my dress red.

These were the men who ran the world. I watched, eyes open. Was this the Golden Land that Jacob brought me to? How is it better, different than Volapzhin? Only what has been lost. Stale air now and no trees. Noise and noise and the clocks ticking. Grayness falling on me in sleep. Or worse: the girls pressing to the windowedge; blueorange spark of flames bursting from behind. As it was in Volapzhin with the horsemen and papa. Death scattered everywhere like salt from a shaker.

I ran like a streak of light from City Hall back up East Broadway to collapse on a bench in Seward Park. So this was the world. This was to be my life. I watched the chessmen playing their games. Stooping suspendered to move sideways their black white knights. With Lea I listened to the speakers thundering of injustice to the scruffy crowds ignoring them. Beneath the brick stiff spine of the Library, towering in newness.

But how my memories muddle! The present presses. The years that came after nosing their way into the times before. No Lea of course in the first days of my walks. But no Seward Park either for there to be a library. Blocks of buildings not yet torn down, and the books in the basement rooms of the old Aguilar Library still smelling of mold and dust. No speakers in the Park, or if there was a Clara Lemlich then I did not know I did not know her.

Why do I have to think always of Lea? Of our days together, and what pleasures there might have been? I want to return to the years before unstained. To the New York when first I saw it. When I wandered the streets fresh without name, the voices without sense. Each strip of paper peeled back to the past, one atop another. Shops that have changed and fled, houses rising and falling. To get beneath the dirt of life and years built up. But I cannot forget what has come since. The nowness seeps back like roots going downward from air to earth, and brings no flowers. Smudging out the maps of what was.

But even then, at the first moment, when we stepped from Castle Garden, before the rabbi and Lea, it was too late. Always it is too late. For it is not this New World that I dream of. When in dreams I walk the lightstrip going forth, in terror it comes round circling. Taking me back only to where I was, tracing the wandering paths through Volapzhin, the shadows of the forest falling close. Even when I do not want to think of Volapzhin. Here the brick house of the Dubinsky’s and there the post where they tied their dog where the rabbi used to stop on his walk home to talk over the Talmud with Berl the father. There the house where Basia lived where in the yard we would play Cossacks and throw each other down in the dirt and mud. And there the tree where Jacob and I met for the first time with heads up to look at the branches, golden curls and the turn of his gaze smiling. But then at the bend where the river nuzzles close to the road rightward a gray wall of fog of forgetting. Inside somewhere the slaughterhouse I know is there but the size and color gone. Wood or stone? Pigs or cows or what? No more the stifled grunts, terror of eyes I must have heard or seen. All faded as in the spring the mist would rise off the river and only the housetops clear. Blotted, blurred, and who knows what beyond.

I stand at the edge of the water and look back at what is drowned and drowning. I want to see again, to remember. Not just Lea, her remnants and reminders. But Volapzhin: as in my New World walks at every streetbend the town comes to me in pieces. Sunset reflections from the synagogue in the glint in the glass of a storefront. The waste of cloth in the streetgutter, bright as in the top drawer of mama’s dresser. From scraps I could sew, if I could sew in light, and the Old World would return. Stitch after stitch into coat or cloak. Market streets on the arms and the smell of horses at the hems. In fabric shimmering of many colors and patterns and shapes. Around my shoulders I place it, soft on my skin, and again I am at home in anywhere, walking the streets as they were. But like water it slips from my back, sinking into the earth, and my eyes open only to New York and the dawn.

Jesse Schotter teaches English at Ohio State University and is the author of Hieroglyphic Modernisms. His essays have been published by Full Stop and Electric Lit.