Cornelius Radhopper, despite the exuberance of his name, is more of an earth-moving, soil-munching entity than a man, somebody who tunnels his way through life, blind to imagination and light, eating his way through the soil of life and feeding indiscriminately on whatever decaying particles that appear before him as his head moves blindly forward in the darkness. He has adapted to this existence very well, his uncomplex mind digging into the day with its pointy end before allowing it to flex and force apart the obstruction in his path and allowing the rest of him to fully enter the space created in order to simply start the process again - a relentless path that leads to nowhere in particular, just a dark unending journey that started at a time most would describe as infancy, but of which he has no memory. In any case, he is not interested in memory, or of thinking about his progenitors, which he presumably had, or of siblings, which he may have had, or of the time he made off with something that did not belong to him, which he most likely did not, given his inability to instigate any initiative, good or bad. This lack of initiative is profound and renders him unsuited to forming any relationship with a fellow since some spark is required to ignite even the smallest and most sputtering friendship, and “spark” is a word that the ambit around Cornelius only stifles, like so many other words beginning with “sp”: sprite, spice, spirit, splendid, spring, spree – all are quietly smothered by those other words that hang off him like goitres, words like slough, sloven, slurry, slush, slow, slave.

Cornelius Radhopper, in his impersonal and indistinct ways, in his avoidance of all individuality, in his remote apathy, in his insipidness, is a perfect fit in the half-world of drudgery that he labours in. He is one of many that toil in the recesses of a process set up long ago to slow down a citizen’s means of attaining whatever is being sought, and if all his fellow operatives were brought together and asked to draw up an agreed summary description of their combined undertaking, the resulting paper would contain nothing more than a bland evasion of any commitment to define their role, not because of a desire to obscure the truth but because not one single member of this taskforce is capable of fathoming his or her true purpose. In this grey and meaningless world of the unresolved and the undefined, no one stands out or leaves a mark other than a paper trail which, like the lubricant secreted by gastropods to ease their passage and at the same time facilitate some kind of communication with its fellows, ends, like all the others, where it began - in a perfect circular trajectory that only colleagues will admire but which, through determined irresolution, adds nothing to the initial course of action embarked on.

The fact that every day is the same to Cornelius Radhopper is not the result of an unchanging routine, but because little outside the thick carapace of his narrow experience can penetrate it, not the collapse from a ruptured aorta of Morris, his adjacent co-worker, with all the accompanying blood-letting, not the naked rampage of his next-door neighbour who let himself in through the one window and urinated all over the plump yellow armchair that came with the basement flat, not a world event like 9/11, of which he is oblivious, and not even the loss of the toes on his left foot after a taxi ran them over and they were left untreated, with no medical inspection, until they withered and dropped off one by one, like small rotten plums, over a period of a week, with no apparent side effects other than a slight limp that is now the only physical trait lending him the slightest particularity when he walks. In all other respects, posture, appearance, presence, he is unnoticeable in a crowd, but more to the point, the crowd, the weather, the day, is unnoticeable to him as he makes his way to the underground and surfaces half an hour later to reach his workplace with its granite entrance where, with small footsteps, he mounts the long flight into the vast unwelcoming maw that is the main lobby.

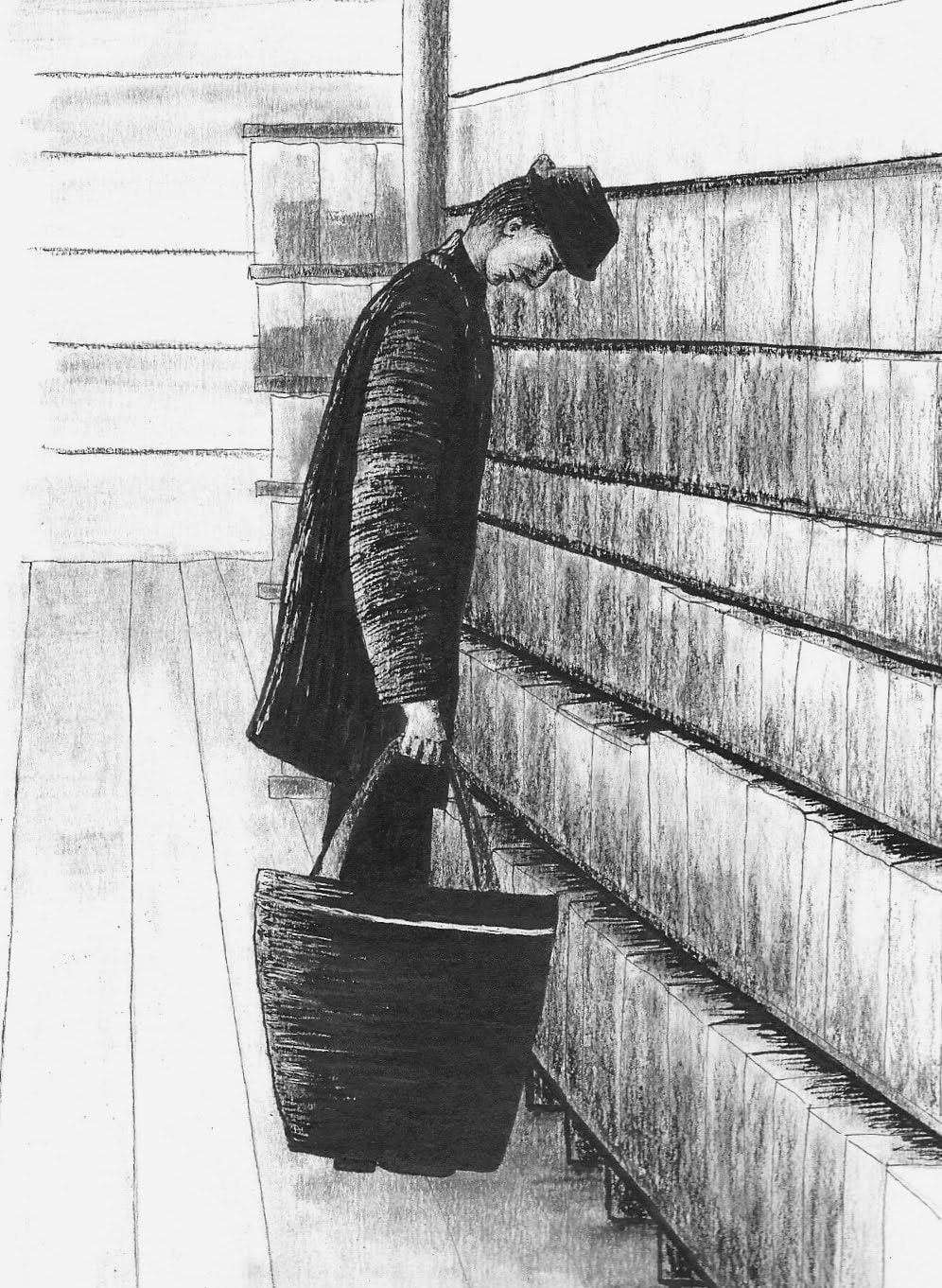

Otherwise, all indications are that he stays indoors, no matter what the weather is like, and only emerges from his small damp quarters to do his shopping at the nearest outlet where he always buys two kilos of dried pulses, chickpeas, butter beans and lentils, half a dozen onions, rice, milk and a loaf of sliced white bread, never varying his purchases and always paying with the exact change in order to minimize any socializing that might be the consequence of engaging Mr Ahmed in any verbal exchange. Mr Ahmed can set his watch to this customer’s weekly arrival, 10 am on Saturdays, and is accustomed to seeing the thin figure edge its way into the shop, the narrow shoulders and head leaning forward as the purchases are selected along the shelves, the carrier bag swaying at ankle level, almost brushing the floor, due to the shortness of his legs in relation to the torso, which rises hipless and straight until it tapers below what must be the neck. Once, when Mrs Ahmed asked her husband about the man, he shrugged and waved the question away. “One of those cucumber-shaped Englishmen,” is all he said.

At work, Cornelius Radhopper has hardly noticed the empty space left by Morris. It has been unused for over a month, and it is only when he hears a trilling “Good morning” in his left ear that he looks around and makes out through his beer bottle glasses that an unfamiliar shape is sitting alongside him. He registers the fact that it is another person, and what is more, a female person. Half the workforce are women, so there is little to be surprised about, but nevertheless he shows neither interest or pleasure as he gives a near imperceptible nod in the required direction and goes back to his task, an appellant’s doomed attempt at persuading authorities to favour his request for its imagination and perception. The task will keep him occupied until midday, by which time his gastric juices will have stimulated his appetite enough to moisten the thin lips which will help direct food, always a bean paste sandwich, into his mouth where his pharynx will coat it in saliva and push it down the oesophagus and eventually further down until it is broken up by his digestive enzymes. His small teeth seem to play only a minor part in the process, and taste, no role at all. He will eat at his desk, like all the others, and speak to no one.

“When’s our lunch-break, then?” The sing-song voice pierces the muffling cocoon of indifference like a stiletto perforating his brain and, in his distress, he turns towards the sound. He looks up and squints to bring the shape into focus. The person, the woman, is framed by the neon strip of light above and a little behind her, so that her hair forms a coiffured halo around a face that gradually coalesces into its component features: black eyes, sharp nose, prominent cheek bones and small puckered mouth bracketed by laugh lines. He stares at her, the tension forcing him to shrink into his chair, burrowing into its cushioned upholstery with his feeble buttocks, and he makes no sound, as if by doing so she might not notice him and perhaps move on to some other colleague. She looks at him with her head cocked to one side so that only her right eye is focussed on him, gauging the distance between them, waiting for the moment he gives himself away with a movement, or any sort of response, before she swoops. The stand-off continues for longer than would be conventionally deemed as necessary, because in most situations a cough or a smile would act as both a time-filler and prelude to an inevitable answer to the question hanging in the air, and the longer it hangs expectantly over them, the deeper the unease, except that she shows no sign of anxiety, only an amused consideration of the stupefied being before her, whose demeanour shows an absurd combination of bewilderment and numbness.

She cocks her head to the right and breaks the spell: “Marula. Just call me Rula.” She smiles and her black eyes glint as she offers him her hand. He looks at it reach towards him and draws back a little. He sees that each long finger comes to a point in a bright red nail, the wrist and arm are lean and unblemished. He is compelled to unsheathe his right hand from inside his jacket pocket, where it has been trying to bury itself, and presents his wary fingers to her. She takes them, her larger hand easily wrapping itself around his, and gives them a considered squeeze, ascertaining something, some evidence, some intelligence, via the tepid contact offered. She keeps looking at him, and waits.

Deep inside Cornelius Radhopper’s brain something slowly stirs. Awoken by the unaccustomed touch of another being, his nervous system’s long unemployed ability to process emotional information and therefore to experience even the most modest twinge of curiosity, has allowed the briefest memo to meander through the narrow virginal passage of a neural pathway never before called upon to perform, and is now prodding him into a conscious need to respond. It is forcing his mouth to open and make a sound.

“Keurghneel….”

She cocks an ear towards him and looks quizzical.

“Kur…knee…,” is the faint sound that leaks out.

She lets go of his hand, which retreats under the desk, and squawks:

“Corny? I love it! Corny. What a name!”

Cornelius Radhopper wants the ground to swallow him. He wants to dig a hole and burrow down far away from all danger, to curl up in a small moist cavity and simply…be. Unable to deal with the unfolding situation, he can only stare at his desk, which triggers his bureaucratic instinct back to the routine of paperwork and soon allows him to forget the she-person next to him as he resumes his task of obfuscation and obstruction. She stands back and turns to go:

“OK Corny. Busy person that you are!”

He does not notice her as she turns and goes back.

At five thirty he is part of the slow-moving throng that makes its way out into the vast lobby where the daily bottleneck at the exit doors further delays everyone’s departure with a laborious queuing system that imposes close contact and awkward shuffling among beings whose primary aim is to reach home as fast as possible. The lumbering mass gives off little energy, and the only sounds that escape it are from coughing and throat-clearing, occasionally punctuated by a comment about the weather, so when Cornelius Radhopper hears a shrill “Corny!” coming from way behind him, he knows that all his co-workers are turning their heads to pinpoint the source and that they all now know precisely who Corny is. He can only lower his head and close his eyes and hope she cannot reach him while his small scuffling steps take him nearer and nearer to the exit and to a hoped-for escape. “Hey, Corny!” the voice a little shriller, like the cry of some predatory creature that has spotted its prey. The glass door is within reach and he is two or three metres away from release. “Corny! Hey, Corny!” The cool air welcomes him, and he starts to move with deliberation down the long flight of stone steps towards the safety of the underground, still hemmed in by bodies, all with the same intention and heading in the same direction, so that his shuffling gait is forced to speed up. He feels secure within the embrace of the throng and can hear a distant “Corny!”, followed by others that wane with time until he is at last at the entrance of the underground and descending the steps into the dank and fusty interior to stand with his fellows on platform five and wait for the train. It arrives promptly and within half an hour he is opening his front door and letting himself in.

It is a two-room space with a low ceiling. He is unmindful of his surroundings, the bare floorboards with no rugs, the stark and empty walls, the one yellow armchair, the narrow bed, the absence of books, of magazines and even of a television, the weak lighting, the dark little kitchen with its tiny trestle table. In this damp burrow, Cornelius Radhopper spends his day horizontally, in bed, or vertically, stretching towards the ceiling, or just sitting in the armchair, while the beans he soaks at room temperature ferment and release their sour aroma.

This familiar whiff does its best to welcome him as the door closes, but his mind is fumbling for a thought that might help him address a growing apprehension about tomorrow, and not only tomorrow but also the next day, and the next, and so on, until…when? Thinking ahead does not come easily to a creature that only lives in the present. He looks down at his left hand. When it came into contact with another hand, he had almost writhed, so sensitive is his response to human skin. What to do tomorrow? How to avoid interaction? Nothing presents itself as a solution and he goes to the sink to inspect the saturated beans.

The days that follow settle back into easy routine, only a chirpy “Morning, Corny” at the start of work, with no attempts at conversation, not even during lunch-break, and a cheery goodbye wave at the end of the day to which he does not respond. He is unaware if she ever looks at him from her desk because any visual contact initiated by him can only lead to undetermined consequences. Work continues apace as piles of documents are placed before him and are gnawed away by his relentless appetite for applying the dead hand of bureaucracy to proposals and projects that appeal to good sense, ingenuity and vision.

And so, weeks go by, maybe a whole month, when he arrives at his desk one morning and realizes that the reassuring grind of daily life is going to be ruptured and that he has been observed all this time, studied and even monitored, by another. There on his desk is a flowerless plant in a small earthenware pot. He sits down and gazes at the tender green shoot sprouting in the rich dark soil and leans in to sniff it. Why does soil smell so good?

His index finger disappears into the earth, and he feels its warmth and moistness and smells the spores, its microorganisms and bacteria. An inexplicable sensuality is trickling via his nostrils into his head and swelling up inside his throat and thorax, filling all parts, his skin tingling and his glasses misting up.

“Climbing Italian Haricot Bean. Wonderful for soups and stews, and even sandwiches! It needs a sunny location.”

He turns to look at the blurred outline. She is leaning in towards him. He wipes the glasses with the frayed cuff of his shirt and sees that she is smiling, one black eye cocked in his direction. Instead of confusion and numbness, a new sensation is rising within, one that seems to contort his wide mouth into a rictus that reveals the neat row of small teeth.

It is a smile.

Then the teeth part and await a command. Then, a sound percolates:

“ Eurghhh. Arghmmm. Th…th…thank you.”

She seizes the opportunity. With a corvine hop, she is standing next to him.

“I know how much you like beans, so I thought….you know…”

She stands over him and he can only look up mesmerized. He gulps at her alarming presence, her forwardness pushing at the walls of his cocoon, unbidden, yet accelerating the pulse of long-dormant sap within, luring him out of his lair, like rain brings out a hibernating toad from its deep leaf litter.

“Yes,” he pipes and is unable to say any more.

The simplicity of his response seems to please her, and she backs away with a smile. Her eye stares at him, her head turns slightly, and the other eye takes over – she seems to be measuring him.

The turbulence and confusion accompany him back home after work, and, even after the door closes, the calming familiarity of his flat is now in retreat. Nothing he does as part of his routine can dull the rising apprehension, the inexplicable mood. It is Friday evening and the hope for a dull weekend ahead is dwindling for some reason he cannot explain. He stands in the middle of the room and waits for the inevitable “something”. An hour or so later, the unprecedented happens.

There is a loud knock at the front door. He closes his eyes for it to go away. Another knock. He waits, hardly breathing. Another knock. He starts to make his way to the door as slowly as possible, but he cannot postpone the inescapable and sees his hand reach for the doorknob and turn it. A slight intake of breath, and he opens it.

“Surprise!” she cries.

Cornelius Radhopper crumples to the floor.

The unconscious state can so often be a release to the afflicted, but this bliss is denied Cornelius Radhopper because it is so brief. He comes to on his back and looks up at the ceiling. He realizes that he has been dragged to the middle of the room and that his shoes have been removed. There is a weight on him. He lifts his head and squints. She is looking down on him. Her face comes into focus, her expression is one of concentration.

She says nothing. He swallows. Her face gets closer, her sharp nose is only a few inches away from his, and her eyes…how they glisten, those black eyes. With the slow hesitancy of a mudslide easing its way through the passageways of an abandoned village, it finally dawns on Cornelius Radhopper that this is the start of something new that will either lead on to another life or bring it to an end.

He can feel her breath on his face now, her eyes so close that he can see himself in them. Her eyes show no expression now, close up they reveal nothing other than blankness, a moist black veneer. In a second, he will know what they conceal, as they move in, larger and larger… Rula, Marula.

Cornelius Radhopper, in his impersonal and indistinct ways, in his avoidance of all individuality, in his remote apathy, in his insipidness, is a perfect fit in the half-world of drudgery that he labours in. He is one of many that toil in the recesses of a process set up long ago to slow down a citizen’s means of attaining whatever is being sought, and if all his fellow operatives were brought together and asked to draw up an agreed summary description of their combined undertaking, the resulting paper would contain nothing more than a bland evasion of any commitment to define their role, not because of a desire to obscure the truth but because not one single member of this taskforce is capable of fathoming his or her true purpose. In this grey and meaningless world of the unresolved and the undefined, no one stands out or leaves a mark other than a paper trail which, like the lubricant secreted by gastropods to ease their passage and at the same time facilitate some kind of communication with its fellows, ends, like all the others, where it began - in a perfect circular trajectory that only colleagues will admire but which, through determined irresolution, adds nothing to the initial course of action embarked on.

The fact that every day is the same to Cornelius Radhopper is not the result of an unchanging routine, but because little outside the thick carapace of his narrow experience can penetrate it, not the collapse from a ruptured aorta of Morris, his adjacent co-worker, with all the accompanying blood-letting, not the naked rampage of his next-door neighbour who let himself in through the one window and urinated all over the plump yellow armchair that came with the basement flat, not a world event like 9/11, of which he is oblivious, and not even the loss of the toes on his left foot after a taxi ran them over and they were left untreated, with no medical inspection, until they withered and dropped off one by one, like small rotten plums, over a period of a week, with no apparent side effects other than a slight limp that is now the only physical trait lending him the slightest particularity when he walks. In all other respects, posture, appearance, presence, he is unnoticeable in a crowd, but more to the point, the crowd, the weather, the day, is unnoticeable to him as he makes his way to the underground and surfaces half an hour later to reach his workplace with its granite entrance where, with small footsteps, he mounts the long flight into the vast unwelcoming maw that is the main lobby.

Otherwise, all indications are that he stays indoors, no matter what the weather is like, and only emerges from his small damp quarters to do his shopping at the nearest outlet where he always buys two kilos of dried pulses, chickpeas, butter beans and lentils, half a dozen onions, rice, milk and a loaf of sliced white bread, never varying his purchases and always paying with the exact change in order to minimize any socializing that might be the consequence of engaging Mr Ahmed in any verbal exchange. Mr Ahmed can set his watch to this customer’s weekly arrival, 10 am on Saturdays, and is accustomed to seeing the thin figure edge its way into the shop, the narrow shoulders and head leaning forward as the purchases are selected along the shelves, the carrier bag swaying at ankle level, almost brushing the floor, due to the shortness of his legs in relation to the torso, which rises hipless and straight until it tapers below what must be the neck. Once, when Mrs Ahmed asked her husband about the man, he shrugged and waved the question away. “One of those cucumber-shaped Englishmen,” is all he said.

At work, Cornelius Radhopper has hardly noticed the empty space left by Morris. It has been unused for over a month, and it is only when he hears a trilling “Good morning” in his left ear that he looks around and makes out through his beer bottle glasses that an unfamiliar shape is sitting alongside him. He registers the fact that it is another person, and what is more, a female person. Half the workforce are women, so there is little to be surprised about, but nevertheless he shows neither interest or pleasure as he gives a near imperceptible nod in the required direction and goes back to his task, an appellant’s doomed attempt at persuading authorities to favour his request for its imagination and perception. The task will keep him occupied until midday, by which time his gastric juices will have stimulated his appetite enough to moisten the thin lips which will help direct food, always a bean paste sandwich, into his mouth where his pharynx will coat it in saliva and push it down the oesophagus and eventually further down until it is broken up by his digestive enzymes. His small teeth seem to play only a minor part in the process, and taste, no role at all. He will eat at his desk, like all the others, and speak to no one.

“When’s our lunch-break, then?” The sing-song voice pierces the muffling cocoon of indifference like a stiletto perforating his brain and, in his distress, he turns towards the sound. He looks up and squints to bring the shape into focus. The person, the woman, is framed by the neon strip of light above and a little behind her, so that her hair forms a coiffured halo around a face that gradually coalesces into its component features: black eyes, sharp nose, prominent cheek bones and small puckered mouth bracketed by laugh lines. He stares at her, the tension forcing him to shrink into his chair, burrowing into its cushioned upholstery with his feeble buttocks, and he makes no sound, as if by doing so she might not notice him and perhaps move on to some other colleague. She looks at him with her head cocked to one side so that only her right eye is focussed on him, gauging the distance between them, waiting for the moment he gives himself away with a movement, or any sort of response, before she swoops. The stand-off continues for longer than would be conventionally deemed as necessary, because in most situations a cough or a smile would act as both a time-filler and prelude to an inevitable answer to the question hanging in the air, and the longer it hangs expectantly over them, the deeper the unease, except that she shows no sign of anxiety, only an amused consideration of the stupefied being before her, whose demeanour shows an absurd combination of bewilderment and numbness.

She cocks her head to the right and breaks the spell: “Marula. Just call me Rula.” She smiles and her black eyes glint as she offers him her hand. He looks at it reach towards him and draws back a little. He sees that each long finger comes to a point in a bright red nail, the wrist and arm are lean and unblemished. He is compelled to unsheathe his right hand from inside his jacket pocket, where it has been trying to bury itself, and presents his wary fingers to her. She takes them, her larger hand easily wrapping itself around his, and gives them a considered squeeze, ascertaining something, some evidence, some intelligence, via the tepid contact offered. She keeps looking at him, and waits.

Deep inside Cornelius Radhopper’s brain something slowly stirs. Awoken by the unaccustomed touch of another being, his nervous system’s long unemployed ability to process emotional information and therefore to experience even the most modest twinge of curiosity, has allowed the briefest memo to meander through the narrow virginal passage of a neural pathway never before called upon to perform, and is now prodding him into a conscious need to respond. It is forcing his mouth to open and make a sound.

“Keurghneel….”

She cocks an ear towards him and looks quizzical.

“Kur…knee…,” is the faint sound that leaks out.

She lets go of his hand, which retreats under the desk, and squawks:

“Corny? I love it! Corny. What a name!”

Cornelius Radhopper wants the ground to swallow him. He wants to dig a hole and burrow down far away from all danger, to curl up in a small moist cavity and simply…be. Unable to deal with the unfolding situation, he can only stare at his desk, which triggers his bureaucratic instinct back to the routine of paperwork and soon allows him to forget the she-person next to him as he resumes his task of obfuscation and obstruction. She stands back and turns to go:

“OK Corny. Busy person that you are!”

He does not notice her as she turns and goes back.

At five thirty he is part of the slow-moving throng that makes its way out into the vast lobby where the daily bottleneck at the exit doors further delays everyone’s departure with a laborious queuing system that imposes close contact and awkward shuffling among beings whose primary aim is to reach home as fast as possible. The lumbering mass gives off little energy, and the only sounds that escape it are from coughing and throat-clearing, occasionally punctuated by a comment about the weather, so when Cornelius Radhopper hears a shrill “Corny!” coming from way behind him, he knows that all his co-workers are turning their heads to pinpoint the source and that they all now know precisely who Corny is. He can only lower his head and close his eyes and hope she cannot reach him while his small scuffling steps take him nearer and nearer to the exit and to a hoped-for escape. “Hey, Corny!” the voice a little shriller, like the cry of some predatory creature that has spotted its prey. The glass door is within reach and he is two or three metres away from release. “Corny! Hey, Corny!” The cool air welcomes him, and he starts to move with deliberation down the long flight of stone steps towards the safety of the underground, still hemmed in by bodies, all with the same intention and heading in the same direction, so that his shuffling gait is forced to speed up. He feels secure within the embrace of the throng and can hear a distant “Corny!”, followed by others that wane with time until he is at last at the entrance of the underground and descending the steps into the dank and fusty interior to stand with his fellows on platform five and wait for the train. It arrives promptly and within half an hour he is opening his front door and letting himself in.

It is a two-room space with a low ceiling. He is unmindful of his surroundings, the bare floorboards with no rugs, the stark and empty walls, the one yellow armchair, the narrow bed, the absence of books, of magazines and even of a television, the weak lighting, the dark little kitchen with its tiny trestle table. In this damp burrow, Cornelius Radhopper spends his day horizontally, in bed, or vertically, stretching towards the ceiling, or just sitting in the armchair, while the beans he soaks at room temperature ferment and release their sour aroma.

This familiar whiff does its best to welcome him as the door closes, but his mind is fumbling for a thought that might help him address a growing apprehension about tomorrow, and not only tomorrow but also the next day, and the next, and so on, until…when? Thinking ahead does not come easily to a creature that only lives in the present. He looks down at his left hand. When it came into contact with another hand, he had almost writhed, so sensitive is his response to human skin. What to do tomorrow? How to avoid interaction? Nothing presents itself as a solution and he goes to the sink to inspect the saturated beans.

The days that follow settle back into easy routine, only a chirpy “Morning, Corny” at the start of work, with no attempts at conversation, not even during lunch-break, and a cheery goodbye wave at the end of the day to which he does not respond. He is unaware if she ever looks at him from her desk because any visual contact initiated by him can only lead to undetermined consequences. Work continues apace as piles of documents are placed before him and are gnawed away by his relentless appetite for applying the dead hand of bureaucracy to proposals and projects that appeal to good sense, ingenuity and vision.

And so, weeks go by, maybe a whole month, when he arrives at his desk one morning and realizes that the reassuring grind of daily life is going to be ruptured and that he has been observed all this time, studied and even monitored, by another. There on his desk is a flowerless plant in a small earthenware pot. He sits down and gazes at the tender green shoot sprouting in the rich dark soil and leans in to sniff it. Why does soil smell so good?

His index finger disappears into the earth, and he feels its warmth and moistness and smells the spores, its microorganisms and bacteria. An inexplicable sensuality is trickling via his nostrils into his head and swelling up inside his throat and thorax, filling all parts, his skin tingling and his glasses misting up.

“Climbing Italian Haricot Bean. Wonderful for soups and stews, and even sandwiches! It needs a sunny location.”

He turns to look at the blurred outline. She is leaning in towards him. He wipes the glasses with the frayed cuff of his shirt and sees that she is smiling, one black eye cocked in his direction. Instead of confusion and numbness, a new sensation is rising within, one that seems to contort his wide mouth into a rictus that reveals the neat row of small teeth.

It is a smile.

Then the teeth part and await a command. Then, a sound percolates:

“ Eurghhh. Arghmmm. Th…th…thank you.”

She seizes the opportunity. With a corvine hop, she is standing next to him.

“I know how much you like beans, so I thought….you know…”

She stands over him and he can only look up mesmerized. He gulps at her alarming presence, her forwardness pushing at the walls of his cocoon, unbidden, yet accelerating the pulse of long-dormant sap within, luring him out of his lair, like rain brings out a hibernating toad from its deep leaf litter.

“Yes,” he pipes and is unable to say any more.

The simplicity of his response seems to please her, and she backs away with a smile. Her eye stares at him, her head turns slightly, and the other eye takes over – she seems to be measuring him.

The turbulence and confusion accompany him back home after work, and, even after the door closes, the calming familiarity of his flat is now in retreat. Nothing he does as part of his routine can dull the rising apprehension, the inexplicable mood. It is Friday evening and the hope for a dull weekend ahead is dwindling for some reason he cannot explain. He stands in the middle of the room and waits for the inevitable “something”. An hour or so later, the unprecedented happens.

There is a loud knock at the front door. He closes his eyes for it to go away. Another knock. He waits, hardly breathing. Another knock. He starts to make his way to the door as slowly as possible, but he cannot postpone the inescapable and sees his hand reach for the doorknob and turn it. A slight intake of breath, and he opens it.

“Surprise!” she cries.

Cornelius Radhopper crumples to the floor.

The unconscious state can so often be a release to the afflicted, but this bliss is denied Cornelius Radhopper because it is so brief. He comes to on his back and looks up at the ceiling. He realizes that he has been dragged to the middle of the room and that his shoes have been removed. There is a weight on him. He lifts his head and squints. She is looking down on him. Her face comes into focus, her expression is one of concentration.

She says nothing. He swallows. Her face gets closer, her sharp nose is only a few inches away from his, and her eyes…how they glisten, those black eyes. With the slow hesitancy of a mudslide easing its way through the passageways of an abandoned village, it finally dawns on Cornelius Radhopper that this is the start of something new that will either lead on to another life or bring it to an end.

He can feel her breath on his face now, her eyes so close that he can see himself in them. Her eyes show no expression now, close up they reveal nothing other than blankness, a moist black veneer. In a second, he will know what they conceal, as they move in, larger and larger… Rula, Marula.

Peter Arscott was born in Peru, went to school in England and later moved to Barcelona where he worked as a teacher and artist. He returned to live in London, working as a tourist guide and exhibiting at various galleries. He lives in Herefordshire and has an art and ceramics studio in Ledbury.